On this week’s program, we delve into the history of the banjo.

There was so much to cover that all of this great music—a salve to the producer in

these stressful days—didn’t really get enough

time on the air. Likewise, the banjo’s story, while indisputably

musical and historical, is enhanced when we incorporate the visual.

Thankfully, the website is here for us. Spotify users can queue on up the playlist—as Leyla McCalla explained, the sound of the banjo is addicting!—and everyone can check out a few pictures from the banjo's evolution. And if you’re looking to really get into the history of the banjo, check out Laurent Dubois’s book The Banjo: America’s African Instrument, which nails that hard-to-hit sweet spot where informative and readable overlap.

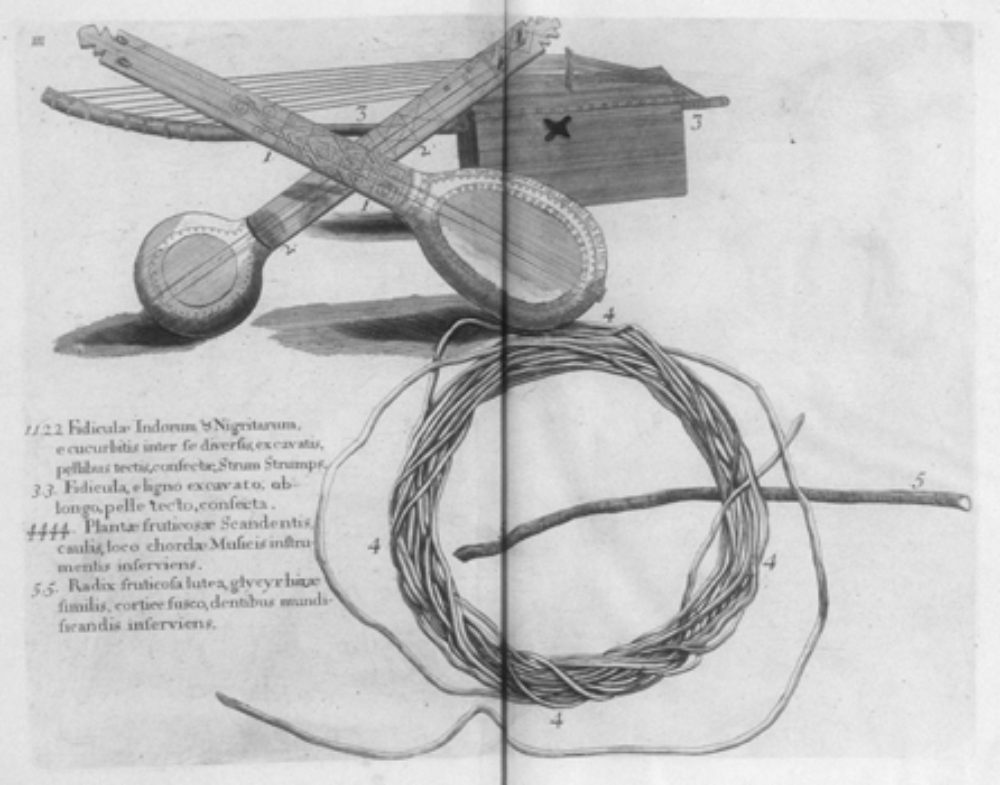

This is one of the earliest existent accounts of the banjo in the Americas, courtesy of the Scots naturalist Sir Hans Sloane, who visited Jamaica in 1687 and published his book in 1707. Already, you can see the differences between these "strum strumps" and their West African cousins like the akonting and the ngoni: the banjo's flat fretboards and friction-based tuning pegs, borrowed from European instrument making. You can't see it in this drawing, but early banjos also had cultural and spiritual symbols on them, like cross-shaped sound holes on the side of the gourd's resonating body.

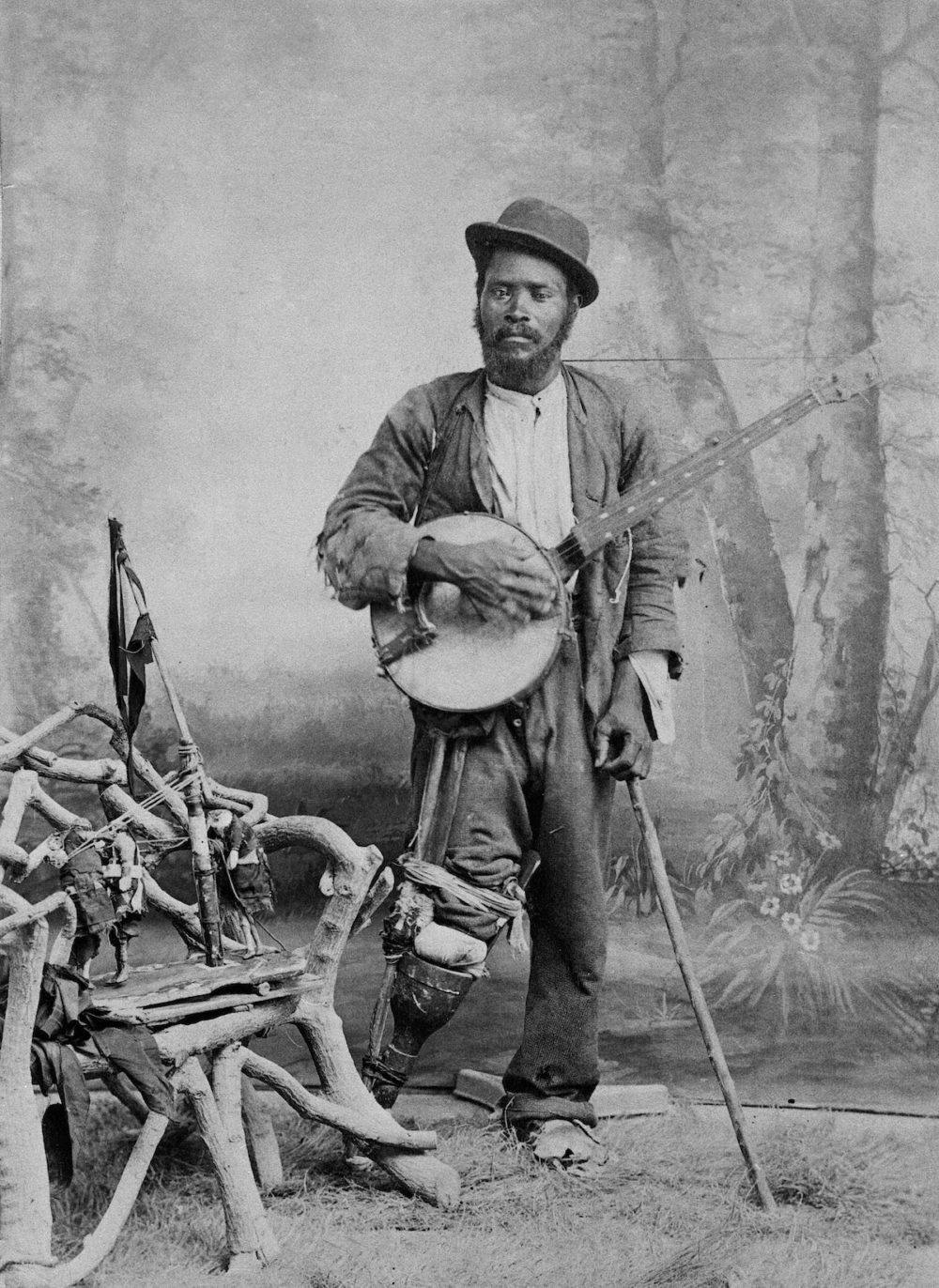

Leaping ahead, we have two images from around 1865, featuring the banjo taking on the shape that's familiar to us today. But if you look closely, strangeness starts to emerge. For example, this woman, in a photograph from Yale's Beinecke Library, is holding a nine-string banjo. And neither banjo has frets yet.

Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection, this studio shot from the same time features a "scoop neck" banjo, also fretless, although with what seems like a more-familiar five strings.

Jim Bollman, from The Music Emporium in Lexington, Mass., in an e-mail to the Wellcome Library in February 2001, explained that "the fretless banjo is typical of the period 1850-1860s with scoop-neck, about six sets of hooks and nuts, 'vertical' fifth peg, etc. The decoration in the fingerboard and matching tailpiece is unusual but not unique for the period (they do mark the fret positions on the board). I can't tell from the photo if the instrument has flush or scribed frets on the board or simply has the rectangular inlays to show the relative positions. It is simply conjecture but he could be a veteran amputee (American Civil War) who either had an act (stage or street) playing the banjo and using the rag dolls as puppets or perhaps was dressed in rags by the photographer to produce an interesting genre photo.

From 1893 we have this beautiful painting by Henry Ossawa Tanner. It's used on the cover of the Folkways collection Black Banjo Songsters of North Carolina and Virginia, and for understandable reasons. The painting was the first of Tanner's to be accepted into the Paris Salon in 1894. His previous entry, The Bagpipe Lesson, was not.

James Reese Europe, founder of the Clef Club Orchestra, here with one of his smaller ensembles that nevertheless featured a handful of banjos. This picture is from 1914, right at the dawn of jazz. Europe drew from African-American country songs, Broadway hits, minstrel tunes and ragtime—he led a dance orchestra after all. Europe's life alone would be a great Afropop program, although the sound quality on the existing recordings of Europe and his groups may give our fastidious sound engineers fits.

This is a video from 1928 of what appears to be Ina Rae Hutton's Ingenues. You can see at this point white people were quite comfortable with the banjo. It's interesting to consider how this context—that of a big-city jazz ensemble—is older than bluegrass music and Earl Scruggs's contributions, which would still be decades away.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles