Blick Bassy is a Cameroonian singer and multi-instrumentalist, living in France and creating highly original African music. These days, he is touring with a trio, playing banjo and singing, backed by cello and trombone. The ensemble is featuring songs from Bassy’s 2015 album Akö, in part inspired by the late American bluesman Skip James. Afropop’s Banning Eyre sat down with Bassy shortly before a recent concert at the Lincoln Center Atrium in New York. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Blick, thanks for talking with us. First, why don’t you give us the short version of your story, your beginnings as a musician?

Blick Bassy: I am an artist, musician and writer born and grew up in the French part of Cameroon, but I’ve been living in France for 11 years. I started with the band Macase with whom I played for 10 years. We made a career in Cameroon, we receive a RFI [Radio France International] award in 2001, a Kora award in 2003 and a Siciba prize. After 10 years with Macase, I decided to move to France because I wanted to go farther, to greet new horizons. Since I started my solo career, I have released three albums, including two on a Dutch label, and the latest, Akö, on No Format which is a French label. I am touring with this album right now.

Let’s talk about Akö. You present it as a tribute to Skip James. Why Skip James?

Things happened in a random way. I was living for three years ago in Nord-Pas-de-Calais, in France, where it is cold. My heater broke down during winter… At this time, I was listening to Skip James, and I had his picture on my studio’s wall, next to those of other people who inspire me, like Ruben Um Nyobe, Thomas Sankara, Marvin Gaye, Charlie Chaplin… My eyes stopped on Skip James, and I was telling myself that even though I was cold, I was almost privileged compared to him, who lived through the '30s, the segregation in the United States. So I took my banjo, started to play a few notes, and after two weeks I had about 60 tracks.

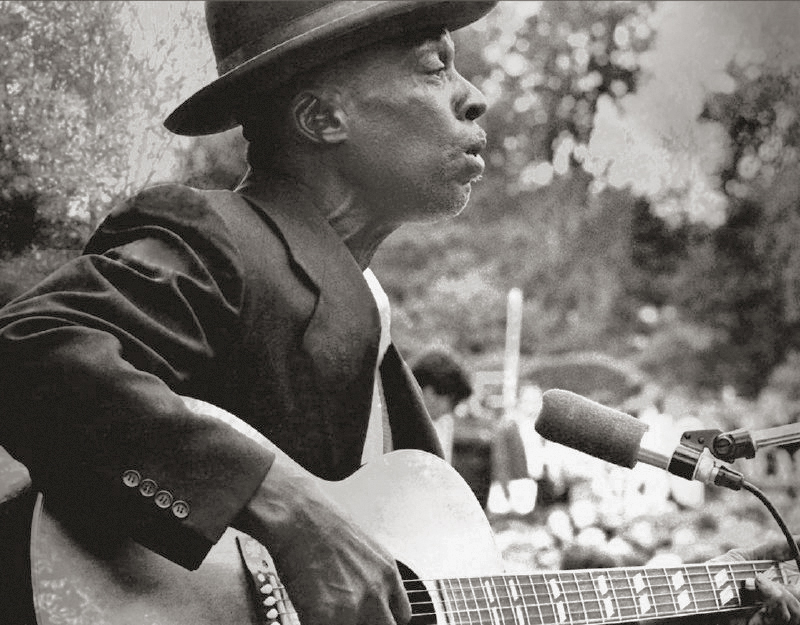

Skip James

What is it that touched you in his music?

Skip James’s music was part of my father’s record collection, with others like Nat King Cole and Marvin Gaye. That was a different kind of listening because I was a kid back then; I wasn’t yet a musician. Then I came across Skip James again much later. I couldn’t even understand what he was saying. I found his voice sad but very touching, minimalist but incredibly powerful. I could understand him without understanding. The emotion was carrying me completely. What he does with very little is incredible. For it was, and still is, the blues itself. His blues is really close to the Bantu blues. Skip James was reminding me of Bantu singers from home, especially an old man who used to travel around my childhood village singing with his guitar.

When I was a kid my father sent me to a very strict uncle to receive a traditional education. That uncle never smiled. The only time I saw him smile was when this old blues singer came to do a concert in our village. I thought to myself, I had to play the guitar, because for me it was a magical instrument that had managed to wring a smile out of that uncle who never smiled. That was my first encounter with music. It had a power! This guy just sang and played his instrument, and I saw a kind of relief on my uncle’s face when he smiled. For three years I had never seen that! I told myself: “How can I have this power and try to seduce my uncle?” [Laughs]

That’s interesting. You know, a few years ago, we did a show called “Africa and the Blues.” We interviewed the Austrian musicologist, Gerhard Kubik, who wrote a book, Africa and the Blues. He listened to a lot of recordings of traditional music. One of the strongest examples he found was one of a Cameroonian woman, singing while grinding grain. It is a sound that, with no explanation, gets really close to the sonority and the tonality of the voice in blues. It is a great mystery…

Absolutely. Because Africa is plural, and so is the blues. When one listens to the blues coming from West Africa, Mali, Senegal, Burkina Faso, Guinea, it is completely different from the blues coming from Gabon, or the one coming from Cameroon, or Congo. Because it comes from the Bantu people, who are completely different from the Mandingo people. West African music is often pentatonic, while in Central Africa it is more diatonic. There are different ways of singing, different griots. For instance, the griots in Cameroon from the Bassa and Beti tribes have nothing to do with the griots in Mali or Senegal.

The origins of American blues are very complex. It is impossible to truly understand them. People who want to simplify things, like saying the blues comes from a particular ethnic group or village are way off.

Yes, because the blues is also an intention, a lament, an emotion. Emotion doesn’t have a village. Otherwise we would know it; we would all have gone there to find it! [Laughs] Emotion is everywhere. It is the interpretation of that emotion, of that intention, that varies from one place to another. For my album Hongo Calling, for example, I wanted to understand where the hongo rhythm came from. It could be found in the Bassa tribe in Cameroon, but also in Senegal, in Cape Verde, in Benin… And it could be found in Brazil. So I went as far as Brazil to know if this hongo traditional rhythm—which was played during mourning and healing ceremonies in Cameroon—had the same role over there. I was surprised because it didn’t at all. It was exactly the same rhythm but placing the first beat in a different place. I began to wonder if it was during slavery that it had reached all the way to Brazil. But it’s a rhythm that is found in other countries. So we realize that we can’t say: "It definitely comes from my hometown." The music appears everywhere, like grass growing in the whole wide world. Although there are different types of grass, it grows all over, and I think it’s a bit similar with music.

Let’s talk about the songs on Akö. Can you talk about some of the songs?

As I say, the album was inspired by Skip James, but I also had an idea about how to improve the human condition, for future generations. I took the term "rural exodus" for instance. Because one of the things that some African countries are suffering from today is migration, with the next generations dying in the Mediterranean after leaving their villages—villages with lands that remain totally untapped. The ones leaving are often land owners. So I try to say that young people leave their villages to go gather in cities, and then once in the city they seek to go the West. They know they are land owners, but they leave the lands because in their mind they have been led to believe that being rich is living in the West. And I simply try to bring them back to reality by saying that happiness, beauty, poverty, misfortune—these are things that must be redefined for us. What are the frames of reference that make a person rich today? Does being a consumer make us rich? Does being in a totally liberal society make us happy? Happiness and all these things must be redefined in every society with respect to these realities, with respect to environment, and with respect to mores and traditions. So that is the work I wanted to do through this album.

For example in "Wap Do Wap," I call on young people not to leave. I draw different pictures: an empty classroom with the teacher sitting in the middle of it; a goat hanging out in the middle of a living room, because everybody has left; I describe a courtyard where there’s nothing anymore, the fruits are falling, they’re rotting by themselves, because everybody has left. Actually I describe a very rich environment, but abandoned by people who go gather in poor places, because they have been led to believe that wealth is elsewhere.

Clément Petit, Blick Bassy, Fidel Fourneyron at the Lincoln Center Atrium (Eyre 2017)

Was your first instrument the guitar?

Yes, the guitar.

Why did you make the transition to banjo?

These days I try to go into things a bit more, a bit like a gold digger, I try to dig little by little. That’s how I started to play the banjo. I play it like a guitar, six strings, standard tuning. But this sound that the banjo has was interesting to me for this album because I really wanted a mix of tones, with the banjo, the cello and the trombone, and to have my voice as the main element. I was looking for this sound, because the banjo also reminds me of the sound of some old guitars of mine. And because I wanted this ancient sound and style, in particular with the inspiration from Skip James, I was really looking for an instrument that would fit into that, and that would bring that. So the banjo seemed like the ideal instrument.

So it’s only for this project. You will get back to the guitar one day.

Yes, on the next project. Actually I like to treat each album like a different project. I may use the banjo on my next project; I may not. Perhaps I will be on to something else. The world is so rich, so beautiful… I am hyperactive and everyday I think to myself that there are so many possibilities to make great projects, going for other things, in other environments. So for sure on the next album I will go on to other lands to seek gold. [Laughs]