Writer Birgit Quade and photographer/writer Lydia Martin visited Dar es Salaam in 2004, and looked into the lives and music of artists in that city's rising hip hop scene. Here is their report.

It was a long taxi ride from Dar es Salaam center to the Steers hamburger restaurant outside town, and we were already late. What seemed to be a disastrous start to an interview turned out to be the beginning of a very exciting journey through the lively Tanzanian hip-hop scene. I was curious to meet them - Tanzania's Top of the Hip-hops. As it turned out it was all very easy; the hip-hop community in Dar es Salaam is small and friendly. Different from what I expected, most artists do not have a manager or agent who deals with the media. From the first contact, it was a very personal encounter. In just one week, photographer Lydia Martin and I went to see more than ten of the hottest artists and groups in the hip-hop scene, producers and promoters. I was amazed by how ambitious and professional the artists are. It was my second time in East Africa and, not knowing much about Tanzania's music industry, I had not expected to find hip-hop such a big business. Most of the artists have been working successfully in the music scene for more than five years, and Tanzanian hip-hop, better known as Bongo Flava, continues to grow in popularity. TV and radio programs are dedicated to Bong Flava, which is also reflected in the sales figures of some of hip-hop albums, eg. T.I.D's album Sauti ya Dhahabu sold over 200,000 copies in Tanzania alone.

Hip-hop is often referred to as a unique means of expression using and combining artistic elements like music, dance, poetry, performance, fashion with attitude, and social discourse. What makes hip-hop a global phenomenon is that its draws upon style, music, and a look that is not restricted to any local region or language. Hip-hop culture and rap music developed in Africa around the same time as in Europe. In the mid-1980s, young people who saw the first hip-hop films and videos coming from America and started break-dancing and rapping. The first large hip-hop scene emerged in South Africa, but soon West Africans - namely Senegal - started rapping and created their own unique African style, which become very popular with both fans in the region and Europeans. In many ways, the rules of hip-hop have roots in the oral traditions of Africa and some say the genre properly originates in the speech song tradition of West Africa griots. Senegalese people in particular point to the local genre tasu as a link between yesterday's griots and today's MCs.

In Tanzania, hip-hop came into the country when the government opened up its economy to outside markets and liberated the media after the socialist era of President Nyerere in the late 1980s. The music came first on imported cassettes, then on the radio and television. "Hip-hop became so big because it is so easy to express yourself by rapping and international hip-hop artists showed us how to do it. I think seeing music video and films from stars like Eminem had a great influence," Mike T said during our interview.

Today, Tanzania has a bustling music industry. It has created its own local musical styles that have been enjoyed around the world for decades--musiki wa dansi, taarab, ngoma, takeu, Bongo Flava, R&B--and is now one of the major hip-hop centres in Africa. Tanzanian hip-hop is normally sung in Swahili, sometimes combined with English, and is related to the Afro-American and Caribbean styles like rap, R&B, reggae and raggamuffin. It can also include elements of the so-called Hindi beats, the Swahili coastal style known as taarab, salsa, or house.

In Tanzania as in America, hip-hop artists are organised into communities or crews. Most of the artists I interviewed grew up in the same suburb in Dar es Salaam, went to the same school and still live in one area. They call it their "ghetto." They consider themselves solo artists, but often perform or go on tour as a team or invite each other to be featured on particular tracks. The communities and the individual artists work closely together throughout the whole process: from songwriting to recording and performing. The recently-launched East Coast Team, a group of seven hip-hop artists, got to together in order to collaborate as a crew. "You see, collaborating as a crew is very helpful for our careers. Promotion is difficult, you have to ring radio presenter and DJs and be nice to them so they play you on the radio," Crazy GK told me. As a team they are more independent and can control their merchandising. As a unit they are strong enough to be provocative in their music; they recently produced a video Ama Zangu, Ama Zao, which caused a lot of reaction and much publicity because of its provocative content.

Despite the rapid growth of hip-hop music during the late 1980s, it was not until the early 1990s that the first album was produced. Saleh J released the first Tanzanian album Swahili Rap. Saleh J combined American rap songs and his own ideas and topics concerning the daily life of young people in Tanzania, communicating directly with his listeners by singing in Swahili. He talked about the 'real' situation ('Hali Halisi'), addressing directly the social, political and cultural issues of youth. More than ten years later, the hip-hop scene has developed its own unique style and language. Hip-hop artists freely mix different music styles, contemporary and traditional, and write intelligent lyrics, poetry, imaginative tales, and create street slanguistics. Many of them are aiming at educating their audiences, often referred to as 'edutainment', and talk about AIDS, poverty, social behaviour and communal life but also about their personal experiences. For example, Jay Moe's first album Ndio Mama is an homage to his mother who died young. Solo Thang's recent songs are about love and his life as a musician. Different from the American hip-hop, these artists' lyrical content is less destructive, racist, and misogynistic, and less interested in parties and sex; it has a stronger social attitude and spiritual aspect, all influenced by the political and social realities of Tanzania.

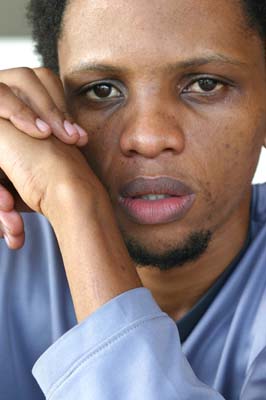

Back in the taxi, we finally reached Steers, a trendy spot for young people to hang out. Mwanafalsafa was sitting in his car listening to music, waiting for us to arrive. Mwanafalsafa, the 'Son of the Philosopher,' has so far released two albums. His latest one Toleo Lijalo was very successful and has so far sold more than 60,000 copies. In 2003, he was voted best hip-hop artist for his track "Alikufa Kwa Ngoma," an anti-AIDS song, at the Kili Music Awards, in Dar es Salaam. He is known for his intelligent and allusive lyrics. "I have this lyrics archive where I collect words, images, lines I pick up or read, and my friends help me to find interesting topics." He prefers to compose and write in English but as he is rapping mainly for a Tanzanian audience, he translates all his songs. "It's easier for me to write my lyrics in English, but I can't compete with foreign stars like Eminem, so I sing in Swahili." Like the other artists, Mwana gets his inspiration from TV, movies, music videos, the Internet and magazines which influence his style, clothes and attitude.

We had a few laughs, and telling him that I was going to meet up with Jay Moe at the Lion he offered to give us a lift. Squeezed in the back seat, he told us that he is very much inspired by soul music, he loves Gloria Estefan, and also enjoys tango music. It was late in the afternoon and the streets were busy with people hurrying home. We turned onto a bumpy dirt road, lined with small houses and huts where people sell food and other goods from small stalls in order to make their living. Mwana - whose name I finally managed to pronounce correctly - nonchalantly steered with one hand the fur-trimmed steering wheel and text-messaged with the other on his Nokia. I was sitting uncomfortably on a cuddly toy: "Oh, this is a present from my girlfriend. We've been going out for seven months now. She is nice and very beautiful. You know, sometimes it's hard to be a celebrity, since my second song 'Girls', I'm very popular with the girls. It's better to have a girlfriend." This is true for most of the hip-hop artists. Different from America where rappers are portrayed as violent and criminal and living outside of society's laws, rappers in Tanzania are very popular in their communities and people are proud of them.

It was almost dark when we got to the Lion, a local garden restaurant and venue. Mwana had contacted Jay Moe to let him know that we had arrived. The hip-hop artists in Dar es Salaam know each other well. It didn't take long for Jay to come, and I liked him immediately. Jay Moe is one of the 'old school' hip-hop artists in Tanzania. He grew up in Dar es Salaam and went to school there, together with Solo Thang, Jahffarai - and Pfunk - a Bongo Flava producer. He knows the hip-hop scene like nobody else, and as it turned out he would be very helpful showing me around and teaching me about the industry. In 2000, Jay Moe participated with Solo Thang, Lady Lu and Jahffarai in the Clouds FM's Star Search Competition. They won and got the opportunity to produce a CD with Bongo Records. After leaving Bongo Records, Jay Moe released his first solo album Ndio Mama in 2002. The album included the song "Kama Unataka Demu," which became an anthem for youth across the country. Recently, he released his second album Mawazo Ya Jay Moe ('Jay Moe's Thoughts'). Although Jay Moe has had a long successful career, he hasn't forgotten his roots and has helped other artists to get started. His style incorporates intelligent word play that tackles everyday life faced by Tanzanians.

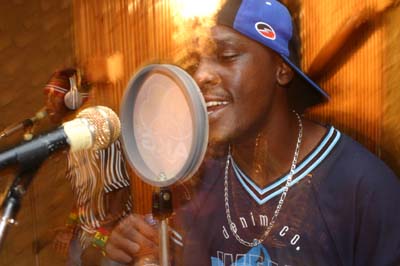

Later, when I met Man Dojo and Domo Kaya, the new stars in the hip-hop universe, I was trying to understand where the differences are between them and Jay Moe. Man Dojo and Domo Kaya's style is softer - less rap and more song and instrumentation - primarily acoustic guitar. This combination sets them apart from the other artists around at the moment. I meet them at MJ's studio just outside the centre of Dar es Salaam. Man Dojo and Domo Kaya had just returned from their first tour of Tanzania. They told me they were exhausted from performing too much, but think that it is good for them to gain some experience. Man Dojo and Domo Kaya are from the largely industrial Tanzanian city of Arusha, unusual in the Bongo Flava scene at the moment. They made their way to Dar es Salaam to get their music career off the ground. Their success has been fast - a combination of good-looks and musicianship and the fact that they're boys from the country. As children, they used to sing in church. In fact, many hip-hop artists started with gospel singing, and then formed a group together.

All the artists I interviewed have been successful in recent years not only in Tanzania, but in East Africa generally, particularly through collaborations with other East African artists, tours and getting their albums played on radio throughout the region. Artists like Jay Moe, who has collaborated with well-known Kenyans like Necessary Noize, now have a growing fan-base across the continent. However, working conditions for these musicians remain challenging, as they were for their forbearers. Today, competition is fierce, with a growing number of people trying to get into hip-hop scene. Even being at the top of the charts does not necessarily mean an artist benefits financially from his or her releases. Usually, a producer finances the production of a song, paying off musicians with a small, one-time, fixed amount and then selling as many copies as possible without paying any further royalties to the artists.

Top artists and those who have been in business for some time, take a different approach. The East Coast Team, Jay Moe, and Solo Thang, for example, cover the costs for production themselves. There is a choice of studios now, offering high quality production, and one song costs between $100-200 to produce. An artist can record an album for around $1,300. Solo Thang made his first album with Bongo Records but did not get the promotion and support he wanted. He decided to do his second album on his own, which involved touring the country, and doing a of work on promotion, merchandising and distribution. On the other hand, the copyrights and distribution rights stayed with the artist. Using this model, more and more artists are becoming independent and taking control of their careers.

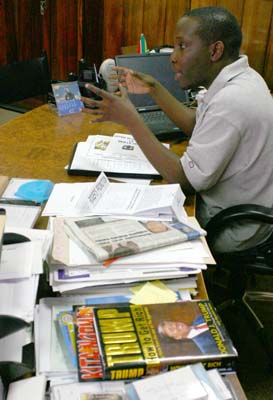

In all developing countries music piracy is a problem. According to Ruge Mutahaba, General Manager at Clouds F.M., 80 percent of all tapes in the market are illegally copied. In 1997, the Tanzanian government made a move to tackle the issue by enforcing a copyright law, but due to the lack of money and resources, violators have rarely been prosecuted. Christine Mosha, PR at U+I Entertainment, has been working for many years in the music business in Africa and the US. She thinks that in Africa, piracy is still not regarded as criminal, and is widely accepted by consumers. In Tanzania, an artist's fan base, different from Europe or the US, is not aware of the financial losses caused by piracy, or that buying original copies supports the artist, not the pirates. "It's hard to build such a mentality," Christine said. Of course, one should consider that people often don't have the money to buy a cassette or CD ($1.2 or $6-7, respectively) in the shops. In Tanzania, the GDP per capita is as little as $600 (World Bank estimate for 2003), despite the fact that income has increased due to recent banking reforms, solid macroeconomic policies and continued donor assistance. The only strategy against piracy that has proved effective so far involves barring tapes and CDs with holograms, and publicly exposing the shops and the people who sell pirated music. The education process continues, for it's hard to imagine real success without the support of the buying public.

Because of pircay, it is difficult for artists to make a living on selling their music; so most of the money they make comes from live performances and dance competitions. Live Bongo Flava shows use instrumental background tracks, and sometimes a pre-recorded chorus. A sound system is used with lighting and DJs play the background tracks. In Dar es Salaam, performances take place in clubs like the Diamond Jubilee, Coco Beach, California Dreamer and the oldest of them, the Bilicanas (Bills). Additionally, artists are touring the country and performing regularly in Arusha, Moshi, Dodoma and other towns. Most artists will pay a promoter to find the venues and take care of the publicity. For an average live performance, a well known artist will get between $300-400, which is relatively lucrative compared to the income from tapes or CDs. There are also cultural concerts, festivals, and dance competitions in clubs and schools, often sponsored by local companies and radio/TV stations. Bigger artists tour in Tanzania, Uganda or Kenya in order to promote their new releases.

Only a few artists have been able to tour in Europe or find a European label to release their music. These include Mr II, T.I.D., and recently X Plastaz, an interesting, rootsy, socially engaged group from Arusha who market their sound as "Masai hip hop." Last year, T.I.D. spent several months in the UK to work on his career. "It was threatening. I was standing alone in the AJ'Z club in London, a crowd of 1,500 people awaiting my performance." Felician Muta, founder of FM Production, said that success abroad means playing to African audiences abroad. This shows that many promoters and producers have a very limited vision to what they can achieve and do not realize the potential for African music to be mainstream, not just limited to Africans abroad. "There are good talented people in Africa. I want to open a big studio to produce high-quality recordings for the international market. This means also to bring experienced technicians from abroad and train others." There has been some interest in East African hip-hop from the European side. Leading the way has been a set of compilations by the German label Out Here Records, including Bongo Flava. Swahili Rap from Tanzania , and X Plastaz's Masai Hip Hop. Rough Guides in the UK has also released The Rough Guide to African Rap.

In Tanzania, the music industry still lacks international business relationships needed to market their music effectively. Recently, hip-hop artists, producers and labels have started to organise workshops and conferences to build international networks and develop more expertise, hopefully with increasing success for the Top of the Hip-hops. "The growth of our music industry depends entirely on the people in it to understand the necessity to ride the tide of globalization. They say, if we fail to change with the times, then we should be prepared to become consumers of products produced elsewhere while our own labor force continue to be unemployment--by this I mean the music artist," Ruge Mutahaba concluded in his discussion paper 'The East African Music Industry: The Business Way Forward' presented at the ZIFF Business Forum East African Music Industry in Zanzibar. Or, as Man Dojo and Domo Kaya said, "We want to collaborate, meet other artists, communicate, not necessarily make more money, but be part of a bigger community."

For more on Out Here Records, a German label specializing in African hip hop, visit outhere.de. For more on Lydia Martin, visit lydiamartin.net.