In this week’s Afropop Worldwide Hip Deep edition, Diaspora Encounters: Kriolu in New England, the Cape Verdean-American Story, we take a look at the history and music of the thriving Cape-Verdean community centered in New Bedford, MA and other parts of Southern New England.

Today, Cape Verdeans form a cosmopolitan, global diaspora with centers from Dakar to Paris, yet the largest Cape Verdean community is here in the United States. New England has been so important to the Cape Verdean experience that it is sometimes jokingly referred to as the “10th island” of the archipelago. Since the start of the Cape Verdean immigration in the 19th century, people, goods, and of course, music have been flowing back and forth across the Atlantic, keeping a powerful cultural connection between home and diaspora.

Cape Verdeans have a particularly strong and diverse music tradition, ranging from heartbreaking mornas to hip-shattering funaná. Today, in the United States, the Cape Verdean music scene is very much alive. In Providence, Rhode Island, and other New England cities, you can catch an old-school morna jam session or a zouk and hip-hop dance party just about anytime you like.

Here, you can read producer Marlon Bishop’s interviews with our program’s scholars. Marilyn Halter is a professor of History and American Studies at Boston University, and the author of a history of Cape Verdean immigration titled Between Race and Ethnicity: Cape Verdean-American Immigrants 1860-1965. Marilyn, who is married to a Cape Verdean-American herself, got pulled into the Cape Verdean story while living in New Bedford between schools and being asked by Cape Verdean friends to help out on a local project with some archival research. Her research led to endless nights pouring over ship manifests, and a book on the topic.

Marlon Bishop: Give us some background – where is Cape Verde?

Marilyn Halter: The Cape Verde islands are situated 350 miles off the West Coast of Senegal and even though Cape Verde means “Green Cape,” the archipelago is actually part of the sahel desert region and has been plagued by drought and deforestation, so it’s a very arid climate and not very green at all. The islands were first settled by the Portuguese in the mid 15th century, they were uninhabited at the time. The Portuguese wanted to set up plantations, modeled on what they had done in the Algarve region of Portugal, so they brought West African slaves to the Cape Verde islands to cultivate the land, but because of this arid climate, they weren’t very successful at it. But nonetheless, the large African population intermingled with the fewer numbers of Portuguese, to create a completely new culture and society—Cape Verdean Creole.

MB: One thing that makes this immigrant story unique is just how long ago it began. How exactly did Cape Verdeans come to settle in the United States?

MH: There were a few Cape Verdeans who came on whaling vessels even as early as the late 18th century. I think 1790 might be the first official record of a Cape Verdean being in the US, but when we’re talking about significant numbers, the first wave really was between the 1880s and the 1920s.

Without the whale, I don’t think there would have been a Cape Verdean-American settlement. The Cape Verde islands were a stopping off point for the whaling industry. Vessels, mainly from New Bedford, Massachusetts, would make regular stops at the Cape Verde islands for supplies and for salt. When whaling went into decline in the latter 19th century, the whaling captains were having trouble finding crew for their ships. They tended to hire a diverse group anyway, but young Yankee seamen were no longer interested in serving. So when they would stop at the Cape Verde islands, the young men of the islands, who were so eager to find any means of survival, that they just seized the opportunity to work on these whaling vessels.

The ships would put into port back here in New Bedford or Providence, and a few Cape Verdeans would stay. And that was the beginning of a real settlement of Cape Verdeans in the United States. And one of the things that is so remarkable about this migration is that they represent the first group of Americans from Africa to have made the transatlantic voyage voluntarily.

MB: How did later generations get here after the decline of the whaling industry?

MH: Well, at the time, most immigrants who came to the United States in the late 19th and 20th century came through Ellis Island. They were largely Italian, Jewish, Polish, and streaming in in numbers we had never seen before. This was the same time as Cape Verdeans were coming, but they weren’t coming through New York City and Ellis Island and passing the Statue of Liberty en route. What happened was, that some entrepreneurial Cape Verdean immigrants bought up the old sailing vessels and converted them into what we call packet boats for regular sailing between New England and the Cape Verdes, bringing supplies to the islands, and coming back straight into New Bedford with new immigrants. So unlike any immigrant group in American society, either black or white, they came to have control of their own means of passage into this country.

MB: Can you describe what the city of New Bedford was like at the time?

MH: New Bedford, MA, in the mid-19th century, because of the importance of the whaling industry, was the richest city in the world, and it’s kind of difficult to remember that, because really since the early part of the 20th century, since the 1920s, the city and the surrounding communities have been in economic decline. Cape Verdeans came to New Bedford, but they weren’t the only immigrant population to settle here. The city is composed of longstanding immigrant populations and their descendents—the Irish, French Canadians, and also, others from the Portuguese empire were making New Bedford their home, especially those from the Azores. The Cape Verdean population still lives overwhelmingly in the area. To this day, 87% of the Cape Verdean-American population lives in Southeastern New England.

MB: So once whaling ended, what happened?

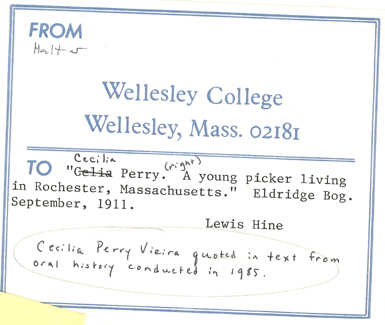

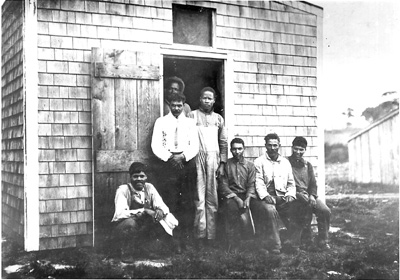

MH: Once these young men decided to try their luck and their fortunes here on this side of the Atlantic, you saw the beginning of families settling here, so women and children relocated and migrated as well. So the men worked as longshoremen, as dockworkers, they worked on the cranberry bogs, and the women, they worked as domestics in the wealthier homes in the New Bedford area. And cranberry picking was a family affair, even young children picked cranberries. In fact Luis Hine, the noted photographer and progressive activist, in trying to curtail child labor took these iconic photographs of Cape Verdean children working in the cranberry bogs in the 1920s.

In any case, this was the kind of work they did. Often it was seasonal, and the downside, of course, is that it made it harder to survive economically. But the upside was that many Cape Verdeans, because they had ready access to the packet boats, made return trips to the Cape Verde islands in the winter when there wasn’t work either picking cranberries or working on the docks.

MB: So they stayed in maritime occupations?

MH: It has been one of the great ironies in the history of the Cape Verdean people that the immigrants to America have been so economically dependent to occupational ties to the water, whether in maritime jobs or in the cranberry bogs. And these were swampy, moist land areas. Meanwhile their homeland has been parched with drought, where the scarcity of water has been the fundamental historical constant. So you have this really complicated relationship to the sea.

And it gets even more poignant, when you think about the islands, sitting out there, more than 350 miles from the West Coast of Africa, and isolated from one another by the sea, isolated from wider society from African continent, from the European continent, because of their geographical placement in the middle of the ocean, and yet it’s been the water, it’s been the sea, the ocean, that has been the connection to their survival, and that keeps them in communication with the diaspora population.

MB: Immigration has been a way of life for Cape Verdeans for a long time – how has this affected the islands?

MH: The migration is so embedded in the Cape Verdean experience that the sense of always needing to separate from your loved ones from your homeland to survive, the idea of constantly having to move from your homeland is a theme that runs through the entire Cape Verdean experience. In fact there are more Cape Verdeans living outside of Cape Verde than on the islands, in the diaspora both here in the U.S. and in other parts of the world, especially Portugal, the Netherlands, to some extent Brazil—not many more, but it tells you just how important transnational migration has been to this society and culture, and not just in recent years, but for the last two centuries.

So you have a population that is continuously negotiating the variables of wanting to stay connected to their families, to their loved ones, to the land that is their own, and wanting to, at the same time, be successful in setting up a new homeland, so there’s this continuous sense of longing, the sense that your missing your homeland, your loved ones, but also the excitement and possibility of a future that’s going to be better.

MB: While we’re on the topic of separation, can you explain the concept of sodade?

MH: Well, you can’t really talk about this sense of what the Cape Verdeans call sodade—the longing, the nostalgia, the desire for home—without talking about the Cape Verdean morna. The morna is a distinctive Cape Verdean literary form, which consists of poetry put to music and conveyed through gestures and dance. And what the subject matter of most mornas has to do with the hopes and the hardships of the people but with the theme of emigration, almost a constant.

One thing I think I want to say is, I specialize in American immigration, and although I’ve written this book on the history of Cape Verdean immigrants, its certainly not the only population that I’m familiar with and that I teach about. And I must say, among all the immigrant populations that I have studied, the link between the migration experience and music is just much more prevalent. Its so embedded, the music is so embedded with the experience of migration, and vice versa, its almost impossible to talk about the one without the other, and that’s not always the case.

MB: What was the experience of arrival and adjustment to life in the United States like for these newcomers?

MH: When the packet boats would arrive in port, it was always it was a big day of celebration and excitement for those who were waiting for their loved ones, if it was a nice day, people would be out on deck and friends would be at the docks. It was always announced in the New Bedford daily newspaper, how many ships came in, who was aboard, and it was really a very exciting and welcoming atmosphere. You may have heard horror stories of immigrants who come through Ellis Island, and they go through the reprocessing center, and now they arrive, they get to Manhattan and there are all kinds of people ready to exploit them, and they may not know where to go. But in a small port city, there was community there and people took care of each other.

MB: What was New England Cape Verdean social and cultural life like?

MH: There was a real richness of the community life among the local New Bedford Cape Verdean population. In addition to sporting clubs and beneficent societies, church groups and worker’s organizations, some of the musicians formed the Ultramarine Band Club in 1919. That’s the club by the Ultramarine Band. They were a marching band, they marched in parades and on holidays, and it spread to being one of the main social venues for Cape Verdean communities, for decades, till today really. But it became an institution in terms of the social life of the Cape Verdean community.

Once the Cape Verdean newcomers got to New Bedford and other nearby areas, they were likely to settle in neighborhoods where other Cape Verdean were already living, which were neighborhoods that were very close to where the Portuguese from the Azores had also settled. They stuck together as a matter of survival. And in addition to building their own community organizations, they also tended to marry within the Cape Verdean community. They quickly formed a rich associational life to support each other. Sometimes, these organizations were comprised of members from a particular island, so there was a Brava social club and a Sao Vicente social club, but one of the dynamics that really contributed to their patterns of settlement was that the so-called “white” Portuguese, those from the Azores and mainland Portugal, did not really want to associate with the Cape Verdean population.

MB: Cape Verdeans were a multiethnic people in the U.S. long before creole and mestizo groups from the Americas settled here in large numbers. How did American concepts of race and ethnicity shape their experiences here?

MH: One of the recurrent themes in the Cape Verdean experience, in addition to the longings, the sodade—is just that. Among the oral histories, you always find discussion of this notion of identity, and it’s ever-evolving in its complexities. The disconnect between how most Cape Verdeans want to be identified themselves, and the way that the wider society or official government records identify them was often not in sync. There’s this constant negotiating, an attempt to say, “No, I’m not Spanish, I’m not Puerto Rican……”

They brought with them a distinctive cultural identity. Migrating freely to New England as Portuguese colonials, thereby they initially defined themselves in terms of ethnicity—they were Portuguese—but because of their mixed African and European ancestry, they were looked upon and treated as an inferior racial group. And although the Cape Verdeans initially sought recognition as Portuguese-Americans, in terms of white society, they were excluded from the Portuguese social and religious associations, and the Cape Verdeans also suffered similar discrimination in housing and employment.

Another facet of this complicated identity structure is that Cape Verdeans then chose not to identify with the African-American population that was already here in the New Bedford area. They quickly perceived the adverse affects of racism on the upward-mobility of anyone who was considered non-white in this country. Cape Verdeans, almost from the moment they set foot on U.S. soil, were categorized as African-American, but that didn’t ring true to their own experience. They saw themselves as Cape Verdeans.

We also spoke with Marcy De Pina, a PhD candidate in ethnomusicology at New York’s City University and a 2nd generation Cape Verdean herself. Marcy is also a VP at Heavytone Records and manages several Cape Verdean artists, and she hosts a weekly Cape Verdean radio show out of New Jersey as well. Marcy specializes in the modern Cape Verdean music scene, and filled us in on recent developments as well as recounting her experiences growing up in America as a Cape Verdean.

MB: Marcy, how do you weigh in on this topic?

Marcy de Pina: It’s funny because, I moved to New York City back in 1994, I think it was, and I was from New Bedford, Massachusetts, where everybody’s Cape Verdean so nobody really ever asked me what my background was. When I moved to New York, everybody kept asking me, “What are you? What are you?” and I’d be like, “Well, I’m Cape Verdean,” and people would be like “What is that?” You know, “Where is that” And that was actually what prompted me to look more into what was that, because prior to that I just sort of took it for granted. I really didn’t think about it too, too much. And that was what got me to go back and to start looking at Cape Verdean history so that I could give people a better explanation. Because it was somewhat frustrating you know, always having people… I learned how to speak Spanish because everyone would talk to me in Spanish because they would just assume that I spoke Spanish, so I learned how to speak Spanish and always having to sort of explain who you are and where that is, I thought it was frustrating at first and then I realized it was an opportunity for me to tell people about my culture.

MB: There were many changing tides in the 2nd half of the 20th century. How did these social changes and struggle for independence in Cape Verde, finally achieved in 1975, affect the community in New England?

MH: One of the really watershed periods for Cape Verdean-Americans, was the 1960s. This was, of course, the Civil Rights movement, but also the movement of Black Pride, and it was also the era of Pan-African consciousness, so different colonies of Africa were organizing to gain their independence, and what started happening is that Cape Verdean young people—now we’re talking about the second generation—are developing a consciousness of blackness and participating in Civil Rights activity and they had been raised to think of themselves in Portuguese, but they started to be much more African-identified, and it was a really interesting inter-generational dynamic that was going on, where the parents were still staunchly maintaining their Portuguese-ness while the young people were exploring and emphasizing their African side.

MdP: Prior to 1975, Cape Verdeans were Portuguese citizens. The Portuguese government strategically separated Cape Verdeans from other Africans. They used Cape Verdeans as sort of mid-level administrators in the government in other African nations, and really consciously pitted Cape Verdeans against other Africans while at the same time never allowing a Cape Verdean to really fully be Portuguese. I do think that prior to 1975, there were more people who felt that they were maybe black Portuguese of a predominantly Portuguese descent. Of course that wasn’t everyone; the revolution never would have happened if that was the case. But since 1975, and since this opening and allowing, you know, other genres of music to come forward, the island of Santiago in particular to have more prominence, and really allowing people to fully see themselves and to see our history, highlighting the connection between Cape Verde and the rest of Africa.

Following the independence there was definitely a shift of Cape Verdeans recognizing themselves as Africans as opposed to European. And now I think amongst young people, most people feel as though they are African, but clearly we all understand that we have a Creole culture and that we do also have many other things, not just Portuguese, but Italian and some people have Chinese, Dutch, British, and a whole host of other people that have mixed with Cape Verdeans throughout the years. We have all of that in our culture, so I do think that most Cape Verdeans recognize that while we are African we also have many other influences both genetically and also in terms of our culture.

MB: Nowadays there is a more recent wave of Cape Verdeans from the islands, how did that come to pass?

MH: The doors to immigration opened up again in the US in 1965 and that meant that Cape Verdeans could start coming once again, but they were also at that time in the midst of a protracted struggle for independence from Portugal, so you don’t see very many Cape Verdeans arriving until after 1975 when the Cape Verde islands got their independence. It made it easier for Cape Verdeans to migrate out of the Cape Verde islands because they didn’t have to go through the Portuguese bureaucracy. They had their own immigration offices set up. And so, since the 1980s, you see a second wave of immigrants, some of whom are still coming from the islands of Brava and Fogo, which were the main islands from which the first wave came, but also you see immigrants from other islands of the Cape Verdes, from Sao Vicente, from Santiago, so it’s more diverse in terms of their island origins. And this population is settling less in the New Bedford area and on Cape Cod, and more in the city of Brockton, MA, in Pawtucket, RI, and in neighborhoods of Boston such as Dorchester and Roxbury.

One of the biggest differences between what I now call the classic wave of Cape Verdean immigrants, those who came a century ago, and the new wave, the contemporary wave of arrivals of the last two decades, one of the biggest differences is that the newcomers today are arriving to a society that is much more aware of and open to multi-racial, multi-ethnic populations. The way that the ethno-racial landscape of the US—becoming a much more mestizo or mixed landscape—has permeated popular culture, people are much more accustomed to meeting people who don’t fit into the neat and rigid categories of black and white.

MB: So are Americans really that much more open today?

MH: Earlier on, when that first wave came here, because there was little understanding of where the Cape Verdean islands were, there wasn’t a lot of familiarity with Portuguese culture, let alone Afro-Portuguese culture, the kind of confusion and bewilderment and misnaming of this group, you know it took a while to raise the consciousness of the American population that was already here to understand just who the Cape Verdeans were and even longer to overcome the gut-reaction prejudices that were just pervasive in that era.

Maybe I’m being too optimistic here, but I do think that there are many ways that we now do live in an age of multiculturalism. Young people are getting multicultural educations. We have a president that is also mixed-race; he could be Cape Verdean! They had been the new face of Southeastern New England a century before we’re talking about the New Face of America, because they challenged our longstanding classifications of race, of color, of ethnicity, of identity, long before the age of multiculturalism, long before the Latinization of American society, long before levels of mixed-race and cross-racial marriages went off the charts. And it’s taken several generations, but I do think that now there is much more integration and recognition and understanding of who the Cape Verdean population is than there was a century ago.

MB: How has Cape Verdean culture been maintained in the U.S.?

MH: You have this very vibrant culture that is continuously being refreshed by a new wave of newcomers, so the language, the music, the foodways, are all continuously being transplanted to the New England region. At the same time, the Cape Verdean-American version of this culture is being passed along, so you have a mix of the expressions of Cape Verdean-ness that have really been maintained in a dynamic and vibrant way. For example, on New Year’s Eve and New Years Day, local musicians would go from house to house and sing mornas and coladeiras and in exchange they would eat canja, which is Cape Verdean chicken soup with rice. That tradition still lives. The Kriolu language that Cape Verdeans speak has been also passed down from one generation to another. And the music, from the earlier era, the mornas and coladeiras, they have been supplemented by cabo-zouk and fununá and other more popular forms but the older forms are still played in the community. And if you go to a Cape Verdean club or you are at a wedding or a christening and music is being played, of course they’ll play the latest songs, but there are always a few mornas or coladeiras and young people know these dances because they are passed along. They haven’t been lost.

MB: Marcy, the younger generation is, more than ever before, part of a close-knit global diaspora community. What role does music play in such a widespread community?

MdP: I can definitely say that without a doubt, music is extremely important in Cape Verdean culture. Music is a part of everything. Nowadays, we have a huge presence on the internet. There’s such a large amount of social sites dedicated to Cape Verdeans throughout the world, and a lot of these sites are centered on music. People exchange files; people download things; people listen on MySpace; people listen on High Five, which is a site that a lot of Cape Verdeans utilize. And then go to a lot of other Cape Verdean sites where they know they can hear music. Cape Verdeans are pretty serious about music, and I think its probably one of the number one ways in which people stay in touch with their culture, and where they satisfy that longing for home.

MB: Would you say that there’s a lot of Cape Verdean pride going around?

MdP: Yes, there is a lot of Cape Verdean pride. That’s almost an understatement. You know, it’s funny because I get together, I promote events and I do a lot of parties where there are Cape Verdean music and largely Cape Verdean people in attendance and people always say that if they’re not Cape Verdean they feel like they are left out. And I think it’s because Cape Verdeans are a small group of people. There aren’t that many of us in the world. There aren’t a lot of people who can speak our language, and I think we’re really proud of that. We know that we’re not big in numbers, so we’re sort of extra proud of who we are because we feel like we have to make extra noise so people will recognize us.

MH: Cape Verde got its independence in 1975, and their Independence Day is July 5th 1975, well it so happens to almost exactly, but by one day, coincide with July 4th, American Independence Day. And here in New Bedford is the only place in the country where our 4th of July parade is a Cape Verdean parade. It starts in a park in the heart of New Bedford, but it ends up in the Cape Verdean neighborhood, and talk about pride. There are just flags and buttons and t-shirts and food and music, but it’s all really about the connection between Cape Verdean independence with American independence. So the pride is, yes, of your distinctive Cape-Verdeaness, but it’s very much in the context of being a Cape-Verdean American.

MB: What does the Cape Verdean-American story have to teach us?

MH: I think the Cape Verdean-American experience teaches us a lot, because we are a society with a long-standing history of racial division, of having put people in rigid categories of black or white. What the Cape Verdean population has taught us—at a much earlier point in our history than the recent wave of newcomers—is that these categories are really meaningless, that our ethnicities are always complicated, that physical features don’t really tell you what ethnic or racial category you belong in, that our identities are always changing, always in flux, and always very multiply-configured. I feel that the expressions of Cape Verdean culture that we have been so fortunate to have been exposed to are a model of what a true multi-racial, multicultural society can look like.