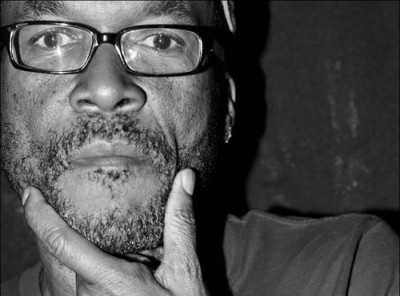

Since launching his career in the 70s, reggae singer Carlton Livingston has worked with the likes of Sly and Robbie, Coxsone Dodd and Winston Riley and scored a number of hits including "100 Weights of Collie Weed." But what many may not know is that Livingston moved the Brooklyn in the early 1980s and cut many of his tracks in New York.

Contributor Saxon Baird recently talked with Livingston for our program "Jamaica in New York" which covers the history of reggae and dancehall in New York City. Livingston chatted with us about his experience coming up as as young reggae singer, the story behind his most famous ganja anthem, the role of posse gangs in the music and life as a reggae singer in the Big Apple.

Saxon Baird: I mainly want to focus on your work in NY. But let’s get a little background first. Can you tell us a little bit how you got into music? I understand you were in some vocal groups early on but you eventually went on to Fantastic Three, Soul Express.

Carlton Livingston: I really started out in the choir because my mother to this day is a church-going person. And she usually sing in the choir. Two of my sisters were in the choir; I’ve got three sisters by my mother’s side and two brothers. And I just gravitated toward singing in the choir. I was born in the country; I left and came to Kingston. I was in the choir but I got kicked out because they said I was disruptive, which I didn’t think was true. It was just that I was young and doing other things. And then my friends started a vocal group up at Excelsior High School. But what happened with the group is that everyone wanted to sing lead except for me –I sing harmony, you know? There was a falling out and every time we had rehearsal, there was always arguing. I just look at them one day and said "Listen, I can’t be bothered." And I wasn’t really interested in music. Now I realize I was listening to my mother and sisters and I realize I was musically inclined. But to me, I wasn’t really into it.

S: That’s really interesting. So if you weren’t really into it, what eventually got you into it?

CL- I had this friend- he passed now- Knowledge, his real name is Doiley. And I remember I passed Grade Achievement, like a standardized test and I went to Trenchtown Comprehensive High School and I met him. He was into music and we started to hang out together. He took me down to 3rd street –that was the first time I ever met Bob Marley and the rest of them down on 3rd street. Because I’m from Eastern Kingston and that’s western Kingston, that’s like two different zones. So Doiley was cool; we started talking music- We went to Beverly’s Records and they were like "Come back Wednesday for an audition" And then we went somewhere else- I can’t remember which studio we went to and they said to come back again. And I said Doiley, "I can’t be bothered." (laughs) He was like "Carlton! C’mon! Let's go" and I said I can’t be bothered with this. I was focusing on other things. So that was it. I went to school, graduated, left school, started to work at the post office –I was a postman. I still wasn’t interested in music like that. We basically went our separate ways. I was like "Eh, cannot be bothered."

S- but then…

CL- We started a soundsystem, Fantastic Three, in eastern Kingston. And I was a part there, and then we started with Studio One and I started to sing. When we started out…Lone Ranger was a singer, I was a DJ. (laughs)

S- I’ve heard that! You guys switched it up!

CL- So I started to sing on tracks. And then this guy named Tony Walcott –he was a Christian –used to do dubplates, had a massive collection of studio one and treasure isle stuff. He heard us and said to me, Ranger, Welton Irie, Puddy Roots..he took us to his house on Saturday mornings, and he would groom us. I remember we had this one song “Pearl” (sings tune) You have to be able to recite that riddim. So every Saturday morning, we started off with that –it was just something we had to start off with, everybody had their turn. And eventually we got our craft together. Ranger was the first to really take it to Studio one. And when my turn come, I went to studio one and I did two songs: “Why” and “Two Hundred Years”. “Why” was released, “Two Hundred Years” was never released. Then after that, went to “Channel One” and “Tale of Two Cities.”

S- Yeah- I actually thought that was your first track.

CL- To this day, it is a very surprising track for me too. I just re-do it a couple of months ago dub-step style for a label in Europe.

S-What was the music industry like in those days in Kingston? I know it was a really politically charged time and you came from eastern Kingston, and in western Kingston there was a divide. What was it like then?

CL: You say it was politically charged because you know it was like eastern Kingston, where I’m from, is like a PNP area, western Kingston is JLP/PNP-assorted, but my location was basically PNP. My friends were affiliated with PNP party. So when I started, my friend- may he rest in peace- Clive Jarrett, he and Robbie Shakespeare – me and Robbie Shakespeare are very good friends and he and Clive Jarrett –so eventually they start to record some work. And then I start to record with them because the affiliation.

We usually went to The Jungle with George Phang and know those people. So it was basically PNP stuff which I never really get involved with- I never really believed in politics. So it was really rough. I remember I went to the studio channel one night and Mars Wells telllin' me to get out the studio. And then when he figured out who I was running with, he said it’s cool. So just like when I did a song for channel 1 –I was supposed to go back and do an album but because of the way it was set up, every time I go there had to wait my turn. And I’m not impatient person, but it was just that there are times when basically my nature is that "Okay, I have enough of this." I’m not gonna come there everyday and wait around because I realize what was going on –they were playing politics. So I'd go back home.

But when I start to go with Clive and Robbie, it’s a different thing. And Sly. I said Clive, they have to let me in now. Because I roll with the big boys. So they realized my friends, so I end up start recording for Taxi. Actually I did it first for GG’s Records with Roots Radics, but it was a little bit slow. So I came to the studio one day and the engineer said to Robbie- "Robbie! Record Carlton's Return to the Jungle!" And Robbie was like Okay! And I was like no I record for GG records, and Robbie was like "Oh yeah? Come sing this song!" So we ended up doing Return to the Jungle which was a massive hit.

But at that time, it was politically charged. And I remember I had to sleep in Channel 1 many nights because there was like gunman outside there firing guns. So once we go in the studio and lock down, we don’t come outside again till morning. Sometimes we sleep on the cold concrete on cardboard. Some days we sleep in the drum room, it was padded so we sleep there.

S: I wasn’t gonna go down this path, but I’m curious. Jamaican music at that time was so prolific. Do you feel that maybe because it was dangerous to go outside at night, and that you were locked inside the studio that is one of the reasons why so much music was being produced? Because you didn’t want to leave?

CL- Yeah! Sometimes! I remember my first album Soweto that I did for my friend Chester Synmoie and his brother, Leon. I took one night on that album because we came, we locked down and ain’t nobody going home. After 10 o’clock ain’t nobody venturing onto the streets, not even dogs. So we ain’t venturing out there. I just did that song in one night! I mean I was young those days, my brain was clickin’. I did like 12 songs that night I didn’t write one, they just came to me with the riddim and I just voiced the album.

S- That’s impressive! Doesn’t happen that way anymore!

CL- No! I have to write now! (laughs)

S - When I was down in Kingston, it seemed like that during much of the history of the music, and especially during 60s, 70s and into the 80s, so much music was coming out that nobody was thinking about categorizing it or getting down the history of it- it was just like music music music music! And the government in Jamaica hasn’t done anything to preserve it at all. Like if you go down to Randy’s [a famous record store and studio] on Parade street, it’s in tatters. It’s not being taken care of. I went there and visited and the guy working there was like “This piano, Bob Marley recorded his first song on it!” And it’s just sitting there rotting away! And I was standing there thinking that this should be turned into a museum! But it also seems like Jamaican government wants to put all the money into the tourist cities –that's where the money is. And tourists don’t really come to Kingston. Most people go to Negril or Montego Bay.

CL: I think part of it is the psychology of the government. Because at the end if the day, if you set up a museum, or preserve that stuff –like I know some guys in Paris they went down to Randy’s and bought a Moog –it was in the studio and they went down and bought it! He used it in his recording, but he bought it because it was in Randy’s studio! And he was like "I’ll put down a couple tracks, but I'll buy it because I just want it" ya know? And it’s the value. Let me tell you what it is too: in Jamaica the mindset is that if it’s old, it’s not good.

S- I’ve definitely heard that before! It’s interesting because I showed pictures of Randy's to a studio owner in New York, he was looking and was like "Some of this equipment is worth $50,000.00 and it’s just sitting there!" Nobody is using it, nobody is preserving it, it’s just sitting there.

CL: It’s appreciating the value of the stuff because it’s old. It’s like I’ll give you an example: I was in Jamaica about a year ago and there was an old 1950s Chevrolet car. So I turned to one of the guys and said if I had money I would buy that car. "Old dem!" And I said "Yeah, they’re old but do you know the value if I fix it up?!" He said "grumble." I said "Yo. Let me tell you something, in Cuba…All the people with dem cars, they make some pretty fine money off it!" It’s an investment, and that’s all they think about- especially the money in JA. It’s sad, but that’s them.

S- So let’s talk about New York. I’m gonna bring up some of the political stuff that you mentioned because I think that a lot of the guys that you mentioned ended up in New York. So I’m curious how that tied into music, or if it did at all. But first of all, let’s just talk about New York city. When did you first come here to record?

CL- I came here in about 1981-82. Yeah, around that time.

S- And why did you come to New York?

CL- Well most of my family was in the states so I immigrated too. And I ended up in New York with my sisters.

S- What was the scene like musically when you arrived in New York? Who did you first work with?

CL- When I first came to New York, it was musically basically just standard stuff. But then I met Jah Life and Percy Chin. So I did a couple singles until I ended up doing a full album.

S- Yeah- you did a lot with Jah life. I know you did an LP, Fret Dem A Fret. What was that like? What was it like working with Hyman and Jah Life? Like what was the process?

CL- It was basically that I choose my riddims –Jah Life choose a couple a dem –and then I do all the writing. Basically everything that I record, I’ve written. But it’s just that to pick the tracks that we’re gonna record it wasn’t like a one-day thing. It took us probably like 5-6 months because I would record some songs and then I would say what next are the songs we’re gonna do? We’re gonna record like 4 more riddims and I’m probably gonna put vocal on 2. And I’ll go back and I go okay, Jah Life: this one is fast, this one is slow, this one is in-between, this one’s about weed, this one’s about this, this one’s about that. And you know we put the album together in about 6 months.

S: So where were you recording though?

CL: Over by Philip Smart. That was when Philip Smart had just built his studio, and we start recording there. I mean they were just putting up like sheet rocks and stuff like that, you know? It was like a basic studio. Surprise. Like that’s, for instance, in 100 Weight of Collie Weed, everyone's like "Oh, is that what you call it in Jamaica?" No, that’s what we call it in Long Island. I mean if you look at the Greensleeve Label, it says Roots Radics. No. HighLife players. It was recorded at Philip Smart’s studio. And it says Junjo was the producer. No. it’s Jah Life that's the producer. It’s just that Jah Life and Junjo was working together; Junjo came to America and heard the song. And he took the song back to play on Volcano. And to this day, that song has never been remixed. Any other time you’ve heard it, it’s just a dub version that Jah Life mix and gave Junjo; we have never remixed that song. To this day!... As a matter of fact, I need ask Jah Life what happened to the 16th track because people hear it and they be like Oh, this tune is back! No. It’s just a dub mix for Volcano. Junjo liked it. Actually Jah Life asked.. to redistribute it because we don’t like the song. Jah Life sent it to Greensleeves. And they say "Eh." Then Junjo take it to Greensleeves. and Greensleeves took it!

S: Well let’s talk a little bit more about the song, because I have a few questions. First of all, I heard that there were actually two versions, because there’s the version where you say 100 weight of collie weed coming from St. Ann’s, but also one that says it’s coming from down south?

CL: Right.

S: Can you talk a little bit about that?

CL: Well that was Jah Life's idea, as usual. You know, I think as a producer he is very under-rated but I mean other than Coxsone Dodd, Sly & Robbie, he is a very good producer. He has ideas. Actually the first cut that we did was "coming from down south." And then I remember one evening he come and he was like I’m going to the studio. And I was like "Yeah?" And he said "C’mon!" So I go with him and he said Say it’s from St. Ann’s because that’s where a lotta weed come from. So we ended up doing two cuts. And it’s surprising, it was after a while I realize we did two cut of the song. And he said Don’t you remember it? I was like No. then he played it back. I was like there’s two cuts, okay cool.

S: I want talk about this song in the context of what was going on at the time. Because the song is basically about these guys who are transporting weed through Jamaica, they’ve got the cops behind them –a very cops-and-robbers kinda thing. But it’s also kind of talking about what was going on then. I mean that was a huge deal. You have these political posses in Jamaica, a lot of them moved to New York. Then what did they do when they got to New York? Start selling weed. I want you to put it in your own words, but can you basically talk about that song in the context of what was going on at the time?

CL: Okay well that song came about- basically our version lived in DC, in Maryland, down that side. But I came in 82, and I was down that side a lot with some guys that I know. And I remember one night, they had a dance and they took me to a house. And I went I get into the house it was like Carlton, come, let me show you something. So I went to the basement and....(laughs). There was this much, weed in my life. That place was reeking... I was like "Yo. It’s cool!" And I spent about 15 mins there. It just came to mind and we were talking and they were like, "Yeah, we’re coming from down south." And that’s how the song came about. It just stick in my head and …just like...there’s 100 pounds of weed in that bag alone...so it’s about the fact that I came to that house that night and see all that weed and write it for the song.

S: I’m curious, and I don’t know if you can speak to this at all, but how much did the posse and the drug running and selling play a role in the music going on in New York?

CL: A lot! A lot because a lot of those guys invested profits in recordings- and some of them have never been released... who knows where the tape went! I did some recording for the infamous Shower Posse... I did some recording for them. And I’ve never heard one release. I can’t remember the guy's name, but a lot of them fall out. I mean I know I did about four songs in a studio up in the Bronx. Because at that time everybody wanted to get into it. People calling them name and stuff like that, ya know? So I recorded a couple of songs for the tourist people but it never got released. I got paid, and that was it.

S: I mean when they called, you couldn’t say no. Right?

CL: Nope. Nope. I mean when certain people call you, you go. And they will deal with you a certain way. ya know, it depends on who you are. Me? They deal with me totally different. Because they know I know certain people from certain place. And as much as they might be from different political persuasion, they know... I don’t know what it is, but they always show me respect. Some people, they disrespect our stuff –different artists, but no one disrespected me. Because I have a philosophy in life: I don’t care who you are, I deal with you the same way until you show your true colors. I deal with you as a man. And whatever you do, that’s your issue.

S-Since we are talking about the role of the drug trade: How much did drugs play a role in changing the music? The main story is that the music changed with the digital era because of the Sleng Teng riddim. But how much did drugs play a direction in where the sound went?

CL: If you know the history and understanding it, you'll see where the changes came along with the music. 84, 85, that's when crack start to come into the thing. Snorting of cocaine. Smoking oolies. Smoking crack. And it start to speed it up because everybody start to get fast. So people start to bum bum bum bum because of cocaine. Most people stop to smoke weed. We do that thing and it slow you down a little bit and give you mellow vibe but cocaine kept going fast. A lot of people will not admit that but its true. The drug of choice changed the vibe of the music. Make it be faster, people moving faster, and a lot of people drop out and had to process to…so you know its just one of dem tings.

S: All these studios and record stores in the late 90's and the early 2000's just kind of disappeared. Why?

CL: Oh yeah. (Laughs). That's a very good question. Things were changing. Part of it was that a lot of people got caught up in a lot of stuff. So people ended up in jail. Some people get hooked. Some people get deported. Some people get dead. So it start to change. And I think…people buying records, people stop buying records like they used to and CDs and all of that. So it just changed up. Most of all though is that a lot of people get caught up in some stuff and just got to disappear in some form or another. And then the record stores started to close down because it wasn't profitable anymore. And then some people started to do other things out of the record store…the law running and dem. you know just one of those things.

S: Was it difficult for you to try and stay out of what was going on all around you.

CL: No. I just stayed out of it. Some of my friends get caught up in it. And I was around them. And I remember, I think in '95 or '96, and this is probably something that most people have never heard me say, but there was a time when people say I was a crackhead. I remember walking into Witty's store and this guy I knew said, "So is Carlton Livingston a crackhead a come?" And I went over to him and I said, "Do you know me to be a crackhead?" He couldn't say a word. But what it was that my friends were smoking and I was around them. See, my friends are my friends, I don't care what you do, you know? If you want to smoke, that's your issue.

I remember I called my mother in Jamaica and she started to cry. And I said, "why you cry?" And she said, "I just heard somebody say that you were now eating out of garbage can and blase blase…" and I was just like, " I am living at my big sisters house! Why you crying?" She was worried I was mashing up and blase blase. So I said to her, "you need to stop it and look at stuff. My son, my second son, went to the second most prestigious prep school in Jamaica! Now if I was a crackhead and down on my luck, how could he be going to that school? But she was old and getting up in age and hadn't seen me for awhile and heard people talking stuff. So I just told her that if my son was going to a private school in Jamaica, and she took him there every morning, that there was no way I could be a crack-head.

S: Let's talk about something a bit more fun. I want to play "Itch It Up Operator" because in the very first two seconds you can hear the buzz of the amps. And when I hear that, it just sounds really intimate to me. So let's listen to a little bit of it and you can tell me what the studio was like and the situation there the time?

CL: Wow, I don't think I've ever heard that song like that before. That was when Jah Life had just built his studio so there was like flaws in it. And actually, Sugar Minott brought that track to him to record some artist on it. And I remember he called me one Sunday morning and told me he had this track and then started to sing it back to me and told me that I had sung this song early over a dubplate for Gyro.

And I remembered it. I had gone to Gyro one night and he had this big reel to reel. And I spent one night just doing dubplates on it for Gyro. So Jah Life said, "you did this song already for Gyro." And I said, "you know how I am, I forget all about that stuff." So he played it back for me and told me what he wanted for it. So I went to the studio and he had just built it. I can see it in my head right now. It was half-finished, just like when I first started working at Philip Smart's. And of course, that was before Pro Tools and things like that. So it was just a 16-track reel to reel and it sounds like maybe something wasn't grounded properly in that. Either the mic was grounded or something which gives the track this buzz. And I just recorded that track on a Sunday at about 11 or 12 o'clock in the morning. No! It must have been earlier because I know we were probably going to the race-track. So we did it early. (laughs). Yeah, we used to say Jah Life was born with horse-blood because he loves race horsing. If you go to Belmont, you can definitely find him over there.

S- How big was the studio?

CL- It wasn't very big, not huge at all. And actually, there was no place in it to have musicians. Sugar Minott brought the track to him and we just transferred it 16-track and put some vocals on it and that was it.

S- So you moved to New York in 1982 and left to live elsewhere?

CL- I've been between Washington, D.C. and Maryland and Jamaica. But actually, to tell you a story, in about 95 or 96, I left New York. Because of the same reasons we were talking about before with drugs and gangs and stuff. I just got up one night at about 11 o'clock and caught the last Amtrak train with a bag. I knew this girl, so I called her up and told her I needed some place to stay. She said OK and eventually we got married. But I just had to leave because of some of the stuff going on. I didn't want to get caught up in it. I figured if I stayed around that sooner or later, as strong as I am, and I had been avoiding it but… And I just remember that things were getting kind of weird, man. So I just got up one night and disappeared. And I remember only three people knew where I was. And then the rumors started up again. They were saying I was a cracked-out, maybe I jail, maybe I dead, I get deported. And to me, that's cool. I moved to Maryland, bought a house, got married, got a daughter, raised my family, and I just stayed away from the music scene for years.

Well, I shouldn't say that. I stayed away from the main music scene but I was still recording for Studio One. I usually would come up here Saturday nights, and Sunday morning you could find me around with Mr. (Coxsone) Dodd. Over a period of time, I didn't have much to do, so I was just writing songs. And after awhile I realized that I had written about 30 to 40 songs for Studio One. Which, very few have been released.

But yeah, I would come up (to New York) , record about four songs. I would tell Mr. Dodd, "Ok, these are the riddims I want." And it would take him probably three, four weeks to find them because they were so unusual. In fact, I remember one morning he said to me, "How do you know all these riddims?" And I was like, "I have them on tapes and that's all I listen to." He thought I was so unusual. And he told me that other people would come around and I want to sing on whatever was in fashion, you know? And I was just like, nope, not me. I have this thing about the music where I like to get things early. Anything I sing on, it has to be mine. That's just me, I just have to put my imprint on the stuff. So I've always chosen unusual riddims that most people don't want to sing on or they don't know about. So once I sing on, its my riddim.

I can give you an example. Take the "Rougher Yet" riddim. When we'd go to dances as young youths, we just adored Slim Smith's "Rougher Yet." It was a song where at the dance, you got to put it on about four or five times. So that's how I kind of got to know the riddim. Then I remember, I once went to a stage show down in Montego Bay. Me and Lone Ranger. And there was this girl…you know, in the young days, the girls gravitate towards us… but then Lone Ranger come and take her away from me! So that's how "Please Mr. DJ" came about. I remember I sat on the hotel balcony that night and wrote that song that night. Then when I went back to Kingston, I was singing it on the sound (system).

So I went to Channel One one evening and this one engineer Soldier was working. I need to give credit to him for a lot of my songs that I do because he would often suggest them to the producers. So this one evening U Brown was in the studio. And Soldier was like, "Hey U Brown, you ever hear Carlton sing "Please Mr. DJ" on the sound?" And he knew so we record "Please Mr. DJ" with U-Brown and that was my first big hit. Soldier was always my favorite engineer because creatively, as an engineer, he could really create great stuff. Just like with "Rumors." That was the last song I did on the album. I was leaving on a Wednesday to come to America and I did it on Sunday.

And usually on Sundays, Bob Marley would be outside his house playing soccer. It would five on five soccer on the concrete. And you would have a concrete block with a stick and you would kick it under that for a goal. And so I wanted to go play with Bob. Because when you were finished playing with Marley, Bob would buy out the cart that would come by with coconut and cane and all that. So after the game, we would all sit around and just eat and drink. So when Bob…you know, no one called him Bob, everyone called him "Gong" back then. So I went into the studio on my last Sunday in Jamaica but I really wanted to go play soccer with Gong.

But then Soldier played the track for "Rumors" and I thought it was too slow. But Soldier made me listen to it again. And I'll never forget " Rumors." I listened to it once, then twice, I got the melody, then a third time I put the vocals down. Then I put down a second vocal which I don't think anyone has heard. And that was it! I finished the album. And then I am in America and all of a sudden I get this phone call from Jamaica: "Oh yeah C, "Rumors" is running the place down here!" And I was like "Rumors"?? I don't even like that song. Honestly!

There are a couple of songs I have as a big hit that personally, I don't like. "Rumors" and "Cold Cold Winter," I never liked those songs. Take "Cold Cold Winter, " it was basically hot in Jamaica. Like really really hot. And this guy Roddy came down and he was voicing with Ranger. So Ranger says, come down and see. That was the way Ranger was with me. So I come down and Roddy was like, "you wanna voice a tune with me?" And I remember he paid me $500 dollars. I'll never forget. So I was in the studio and I started to sing, "It's going to be a cold, cold…" then I stopped and was like, nah! But Roddy said that's what he wanted. So I started singing "Cold Cold Winter" but never paid it no mind. So then I come to America in '82 then I visited Canada in '83. And I found out that was one of my biggest hits in Canada.

Then when I came back from Canada, I did "Hot Hot Summer." I am the type of the person that when the opportunity comes I take advantage of them but those songs, I never really liked them. They never really appealed to me.

S- On that note, did you ever have an audience in mind? Particularly, when you were in New York, were you trying to appeal to a Jamaican audience?

CL- I just record. I never focus on the audience whether Jamaican or anything. For me, I just hear a riddim and I vision things and I immerse myself into it and just write. Robbie Shakespeare always said, "Carlton, just record and do the best you can." Don't ever get up on this whole song is this and this song is that. Because you can not tell what the song is going to be. It has to be the whole audience. So I tell people, every song I record except "Rumors" and a couple other songs I didn't particularly like, I've got to like them. And basically, I like most of what I record because if I don't like it then I don't want to record it. I never focus on the audience when I record because I think when you do that, you start to pigeon-hole yourself mentally. Most of the songs I wrote for no particular reason. And certain people just gravitate towards them. That's just me.

S- Coming back to New York, you worked with Bullwackie, correct? But you only released a single track.

C- He has about for to six tracks with me.

S- He's an interesting person to me because a lot of people consider his sound to very "New York" but his production never found him popularity in Jamaica. How did you end up working with him?

CL- I would go up to the Bronx some times with some guys like Mikey Jarrett and thats how I met Bullwackie. But to be honest, I never really liked his sound. But the sound was unique and after awhile you realize that. And I remember I went up there one weekend, I got some tracks, come and put some vocals on it. So I agreed and he gave me the tracks and I listened to them and I remember, he was living in New Jersey at the time. So I took the train over there and I recorded about four tracks for him. "Whose That Man?," and…thats the only one I can remember.

S- Well that's the only one that came out.

CL- (Laughs). When I recorded that, I was going through a hard time. A woman, the only woman I had really loved, had left me. Then after awhile a friend said to me, you realize all these songs you are writing are about. And it dawned on me. So when I wrote "Whose That Man," it was about how someone had seen her at a party. So I said to her, "whose that man you were dancing with?" and I wrote the song. And when I recorded that song, I was still trying to get over her. The riddims were so weird but it just fit my mood and that writing.

I appreciate this, man. Because you're right, the music environment in New York was special, and I never really heard people talk about it. Me and Jah Life talk about it sometimes. In those days, a lot of stuff come out in New York and…I dunno if people just put it on the back burner or what. But what I think is that its this thing where in everyone's mind they think everything came out Jamaica. ….A lot of good stuff was recorded and come out in New York in the 80s and into the 90s. And you know because of this perception that everything come out of Jamaica, when you record here its like them look down on it. And for me as an artist, I always look at them and say, "yo! Most of the stuff I recorded was in America." A lot of Studio One stuff, Jah Life stuff, Wackies stuff. The early stuff…like "Trodding Through the Jungle," "Please Mr. DJ," the early stuff …but most of the early stuff I recorded in New York. And when I go back to Jamaica, I record some stuff. I recorded for Junior Reid, who hasn't put anything out. I recorded for Jammy's whose released one song! I recorded a whole album for him.