Salvador, Bahia--Brazil's most African region--is said to have the country's most creative Carnival. As with Recife's Carnival, it's a highly participatory affair that unfolds in various parts of the city. The central action is a procession of semi-truck size sound systems called trios electricos. In the old days, there was simply a trio of musicians performing atop each of these rolling parties. But these days, large bands play, blasting out their melodious pulsing sound to all within earshot. Each of these booming mammoths is surrounded by a cadre of fans associated with the band or afro bloco up top. These folks form a rope line that serves to clear a small perimeter around the trio as it moves slowly through the city streets. And I mean slowly. It can take 30 minutes for one trio electrico to pass you.

The procession begins at the tip of Salvador's peninsula, near its iconic lighthouse. The legendary afro bloco Olodum led the procession this year, moving past the prime camarotes (party boxes), notably Expresso 2222, hosted by the esteemed composer of a classic song by the same name, Gilberto Gil!

The crowding in this part of Salvador quickly becomes intense. By nightfall, there can be scuffles on the rope lines surrounding the trucks as those manning the lines force their way through the dense river of people. I saw one young beer seller bravely battling to hold his position as people around him were being literally lifted off the ground when one trio turned the first corner just a little too widely.

For all this, the crowds stay happy, drinking beer and caipirinhas, and frequently breaking out into song when the year's big hits and favorite old songs blast out. The characteristic dancing in these jam-packed surroundings involved jumping straight up and down. Really, there's no other option if one wants to move. Hence the term for these street celebrants: pipoco or "popcorn."

These days, Salvador's Carnival is extremely well policed as pods of policemen snake through the crowds, all in touch with one another by walkie talkies. If you have a problem, the street posts are marked with codes that pinpoint your location, and help can be quickly on the way.

While the day-and-night-long parade of trios electricos draws the biggest crowds at Salvador's carnival, there is arguably more fun to be had in the old city, Pelourinho, where drum and brass ensembles parade on foot through elegant, colorful colonial-era buildings. This is the true home of blocos like Olodum, Ile Aye and these days, a number of all-female blocos, such as Banda Didá.

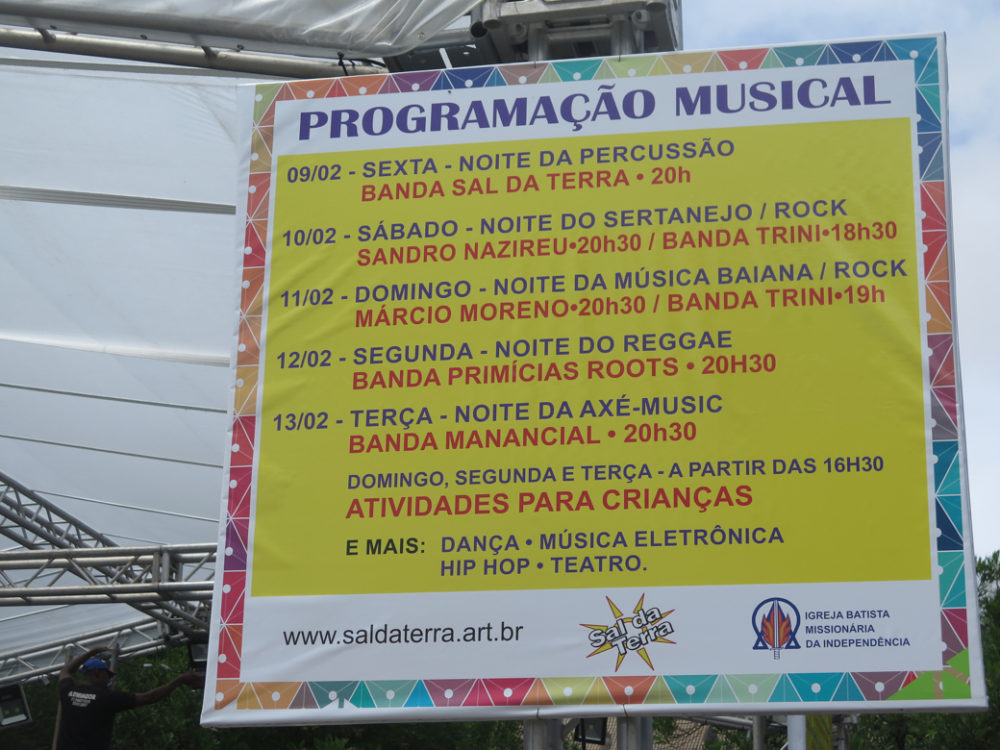

Here, as in Recife's carnival, the crowds are less intense and it's a family-friendly vibe, with lots of kids spraying each other with foam and glitter. There are also a number of stages where well-known bands perform, some of them set away from the street and quite isolated from the general din of Carnival. There are many options, enough to keep the party going for days, as it does every year in February.

As one local told me, during the era of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the bay of Bahia in which Salvador sits "absorbed more enslaved humans than any other port of call during the long course of mankind's history." This resident laments what he sees as the commercialization of Carnival and Carnival pop music--once marketed as samba-reggae or axe. But he also points out that it was the black music of this region that changed Brazil's cultural identity forever, providing the essential seeds of samba, bossa nova and many other musical forms. If you visit Salvador and want to hear more about all this, be sure to visit this gentleman's record store, Cana Brava.

The Bahian love of reggae is impossible to miss. Near the end of one Carnival night, I passed three different stages where three different bands were covering three different Bob Marley songs!

But at the same time, this is an event with an overwhelmingly local vibe and identity. One of the most visible marks of that is the blue and white regalia of the Filhos do Gandhy (Sons of Gandhi), long presided over by Bahian maestro Carlinhos Brown, and these days overseen by Gilberto Gil himself. During his years as Minister of Culture (2003-08), Gil did a lot to enshrine Bahian traditions such as the Filhos in the permanent tapestry of Brazilian culture.

The Filhos are evident throughout the festivities, but on the last day of carnival, they gather in Pelourinho for a night-long parade through the city, en mass dancing and singing to their signature ijexá rhythm, rooted in the distinctive, animating bell pattern of Oxala, the God of Creation in the Candomble religion.

Every year, local artists compete to create the official song of the year's Carnival. The winner is determined only after the end of festivities through a process I cannot say I fully understand. But rest assured, many, many people participate in the choice. This year's winner: "Popa da Bunda" by Psirico featuring Àttoxxá. There's no official video yet, but here's a video of the song made by local street dancers: