Carol Muller is an enthnomusicologist at the University of Pennsylvania. She has written extensively on South African music. Producer Simon Rentner recently spoke to her about jazz in South Africa and beyond.

Simon Rentner: What is it about South African jazz that you find so appealing?

Carol Muller: Of course what I find appealing is that I'm also South African, so there is a certain connection. There is a certain, perhaps you could even say cultural pride in defining what this is. For the American jazz community it's important. But when I listen to South African jazz, both the very international sounding and the more local sounding, there is some sense in which it just evokes a sense of home for me.

S.R: I was really struck with your syllabus actually. I thought a good way to start this interview was to ask you the questions that you asked your students after reviewing all of the materials and hyperlinks that you received. In your view, does South Africa have a history of jazz, distinct from the sounds and creators of American jazz?

C.M: Well, definitely South Africa does. South African jazz is something very distinct. But to think about how that history is formed, it is a different notion of what history is relative to the American story, simply because it is a derivative history. It is a history that is derived from the arrival of sound recordings in South Africa from the United States. So the way in which you have to think about what is historically relevant is perhaps different from what we have done in the past.

S.R: When I interviewed Hugh Masekela and spoke to this other pianist, Rashid Lanie – I don't know if you're familiar with him — it was interesting, because I said, "Okay, is jazz African or is it American?" They made the case that it was African, which I thought was very surprising.

C.M: Well, people will claim jazz is African, because they are reclaiming it. There is a kind of continuity and authenticity that you construct in that way. But I think, right from the beginning, people have heard what African-Americans are doing, and this is right in the journalistic record in South Africa certainly, as being Africans in America. So they have identified what is happening really as Africans making something in a modern way or in a particularly American way. But in the end, Africa is where they come from.

S.R: So you are saying then that the argument of the concept of swing certainly came from Africa. There are no recordings where you can actually prove it for instance, but obviously the scale of blues and the blues notes can be traced to Africa as well. But is that enough? The fact of the matter is you look across the continent of Africa and radio did make it to all different kinds of countries – to Ethiopia, to Senegal – and jazz certainly has influenced all of these musics. But in South Africa, swing really took root. How do you explain that?

C.M: Well, I think Abdullah Ibrahim probably is the person who can best explain this, because he would say that there was a group of Angolan slaves, who were dropped off in South Africa in I think the 17th century, just after Jan van Riebeeck, the Dutch colonist, created his refreshment station in Cape Town. His argument really is that the same kind of groups of people went both to the Americas and to South Africa. So perhaps there is even some parallel development of musical style. Now ultimately is it all jazz? Well, people will claim what they want to claim and provide the evidence and hear it in ways that they want to hear it. But certainly in the Cape the summer feel of jazz, Abdullah would say comes right out of Angola as does a lot of the music that went for samba in Brazil for example and maybe moved up to North America after that. So I think there is a lot in which we can dig a little deeper. People will laugh at the speculativeness of this. But I think that these are things that remain to be explored. But I think we should be willing to hear what people are hearing themselves, because I think we all hear differently and we hear it in terms of the archive that we bring to the table with us and to our listening.

S.R: Well, if there is a distinct sound of jazz in South Africa and it's different from America, what is it? What are we listening for?

C.M: This is controversial, even for South Africans I would say. I'm going to give you an example. I interviewed the Cape Town pianist Henry February, who died a while back. He said, "Oh no. There's no such thing as Cape jazz." – because that's in our marketing category – "All what we play is jazz, which is a universal language." Why he embraces that is that he feels that if he were to travel, he would be able to play jazz with anybody who knows the language, who can improvise, who knows the history as it is American derived.

"If you carried an instrument and you were black, it was assumed that you were a thief. It really became impossible. Then, in the mixed clubs that were in Cape Town, for example, they would send in undercover white people and they would fraternize with the women of color. Basically, they were sent in as spies and, the next day, the place would be shut down. It was ugly."

S.R: So what does that mean?

C.M: I think it means that there are lots of ways of hearing what jazz is, which is why probably there is so much conflict over what jazz is, because it is an open language. Yes, there is a kind of canonical history that came out of the United States. But people listen to this music all over the world. They imitate it. They created exact copies. Sometimes they would claim in South Africa they were better versions even than the recorded versions. Of course, they were being performed live. So that's why it did feel better. It was more alive. It was their own musicians making the music. I think the wonderful thing about jazz is the openness of the paradigm as it were, so that you can insert yourself into its story in a way that perhaps you can't with European classical repertory. It's a written thing and you have to play it exactly. There is no way to put your own – you can put your own emotion into it and your own technique. But it's not the same with jazz itself. That said, I think particularly in post-apartheid South Africa, there is a very self-conscious effort to make jazz both international and local. I think the two coexist and almost that is what defines what South African jazz is. Then of course there is the sound that comes out of Cape Town, out of the Cape Town experience, led by Abdullah Ibrahim. But certainly, as he was nurtured by his own community – Robbie Jansen, Basil Coetzee – some of those early musicians definitely developed a sound in jazz that incorporated local sounds, local musical experiences. It was the memory that Abdullah Ibrahim carried with him first just out of the country and then into exile. It was his longing to make the music that sounded like home that made him create a sound that really was peculiar to certainly the Cape experience, but came to, in a way, speak to a larger South African sound in jazz internationally.

S.R: A lot of the recordings you gave me, the compilations of the early bands, the elite swingsters, the Jazz Dazzlers, there is all this reference to swing jazz in the title of these bands as if they were trying to take ownership of that word. What are they doing there? Here, in the United States, it's just a quartet. It's just a trio. But in South Africa there is this signifying involved with taking the word jazz, in owning it for themselves. How do you explain that?

C.M: Well, I think perhaps the time at which this taking ownership of jazz as a borrowed musical language – and it was borrowed. It was developed elsewhere, even if people can claim that it came from Africa originally. It was something that then mutated in the United States and was recorded there and created its own canonical history. So it was a borrowed language. But it was a language that felt familiar enough. It felt more familiar than a lot of other music that was being foisted upon people of color and African communities in South Africa. So there was a sense in which there is a cross rhythmic interplay. There is a feel of swing. The body does want to dance and to move with the sounds that you're hearing. It's at that level that we need to think about jazz and swing in South Africa.

S.R: Well, the thing that's interesting to me is, in the United States, you say jazz and there is obviously a sound that is associated with this. It's the 4/4. It's the high-hat symbol. It's the sound of Benny Goodman in the '40s maybe, in the Golden Era, and then of course the bop that goes on. Jazz, to me, definitely sounds like Abdullah Ibrahim too. Throughout his career, he definitely sounds like he's playing jazz. Now a lot of these early bands sound more like dance music. It doesn't sound like jazz to me. It has jazz elements. It's jazzy. But it's not exactly jazz.

C.M: No. That is an interesting point. In fact, the musicians from the '50s in particular, with whom I have spoken will say that they did play for dances. That is what they were. They were dance bands largely. But they did lots of other things as well. So there actually are jokes that the musicians tell. Henry February told me a story. In the 1950s, when they just decided they wanted to ad lib or improvise, the people at the dance hall basically threw them out. They weren't hired back again because you had to keep strict timing. So on the one hand, that was your bread and butter. That's how you earned your money. On the other hand, the music you really wanted to play there wasn't a big support for. There were clubs. There were clubs all over in Johannesburg and Cape Town. But they were very short-lived, because it was impossible, especially from the early '60s, to keep those things running with mixed audiences. Jazz attracted mixed audiences – that kind of jazz. The really improvised, swinging, individual expression stuff was a mixed audience and often actually also a very international audience. There were people who came to South Africa for short periods of time. That's important, because when people went into exile, they connected up with musicians who had been with them in Johannesburg and Cape Town or the audiences who had. They helped them make connections in Europe. So yes, it is dance band music – the early stuff, because that was basically how you made your money. That was the respectable music and that was the music that got recorded. What we don't know so much of is what didn't get recorded, what was happening after hours in the jazz sessions afterwards. That's what we have no record of. So what we tend to think of is only what was recorded, which is very, very little in South Africa, because recording was largely dependent on either Gallo Records, who was a commercial recording outfit, but very hand-in-hand – had to be with apartheid policy – then there was the South African Broadcast Corporation, who did transcription recordings really for radio broadcast, but very much in line with a particular kind of ideology.

S.R: But in these recordings they are in a sense labeling what they are doing as jazz. But it isn't jazz at all. It's dance band music, right? So in a way they are taking ownership of this word and making it something else. Isn't that what they're doing though?

C.M: This is a little speculative. But it might be that, in those early days, the kinds of people that they heard as jazz musicians would have been people who were played on some of the commercial radio stations. South African Broadcast Corporation played some jazz on and off, not a lot. But there were other radios that broadcast, for example, LM Radio out of Mozambique. They were very, very popular with the white liberals and anybody else who could tune into them. They played a lot of commercial, swing kind of dance band music. So if it had been presented to people, they would have heard it as a kind of jazz on the one hand. On the other hand, there are also the films that were shown in the black townships and the urban areas, really as a mechanism of social control. The two biggest movies were Stormy Weather and Cabin in the Sky. Cabin in the Sky is with Duke Ellington and Lena Horne. Duke Ellington is there as the band leader. But he's also known as a jazz musician. But it's a club. They are dancing. So do you see where people could have just said, "That's jazz."? It doesn't really matter what the canonical history was. At that point there weren't really histories being taught. It was simply what people saw Africans or people of color in America doing. It came to them through the most commercial of venues.

S.R: So, that's exactly it – this art/music. Did it also represent something else? Did jazz represent what it meant to be modern, what it meant to be cosmopolitan and all of these other ideas too?

C.M: Oh, absolutely. As I was saying to you, what we know of it and what we can hear now is really only what was commercially viable or seen to be racially acceptable too. So let me give you an example of that. There was a dance band musician, Jimmy Adams, who was a saxophonist. He did a lot of arrangements. He went into the Cape Town townships and he met this musician, Tem Hawker. Tem Hawker had traveled the world with the South African Navy and learned to play a lot of music. He heard these African musicians playing Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey, that kind of music. He learned from it. Then he wanted to cross over racially. So he wanted colored musicians, and colored means people of all kinds of mixed racial heritage that aren't white mixed racial heritage, to play this kind of Big Band music. He went to the SABC, the South African Broadcast Corporation, where he had a contract to produce clearly colored dance band music. He took them all his scores and they weren't interested. They said, "Colored people won't be interested in African music or black sort of music," or Bantu music as it was known then. So in other words, the SABC wasn't willing to cross over racially. This becomes a big mechanism of integration in the late 1980s. But in the '50s, it's very clear. Jimmy Adams was so angry that he actually walked out of the SABC and broke the terms of his contract completely, because he just felt that, in the end, it was kind of a racism that he couldn't stomach and he couldn't abide by. About six months later, the great recordings by the SABC that are now available came out. But they were geared only towards a black African audience. So the hurt runs deep for a lot of these musicians, who were involved in this kind of blending and crossover, as it was defined in South Africa in the 1950s.

S.R: So if you were then to call the so called jazz craze – Abdullah Ibrahim talks about being jazz crazy and the society was jazz crazy – what was the height of jazz craziness in South Africa? What years are we talking about?

C.M: We definitely are talking about the late 1950s and the early '60s. This was the heyday of I think political optimism, but musical optimism as well. So this was also the period in which you had all these traveling variety shows, but also that featured so-called African jazz. Although the musicians now laugh about it and say there was very little that was African about it, except maybe people were singing in local languages when they were singing in front of a band. So the heyday was definitely that moment. This is the moment when you have the formation of Chris McGregor and The Blue Notes, which became the Brotherhood of Breath and Abdullah Ibrahim's Jazz Epistles with Hugh Masekela, Jonas Gwangwa.

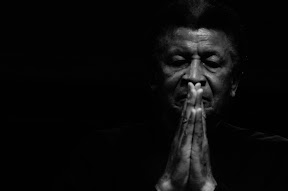

Abdullah Ibrahim

S.R: Let's move from there and look at this record. Of all the CDs of the recorded history of instrumental music or so-called jazz influenced bands, you have all this interesting dance music. Even with the Pennywhistle tune you hear some jazz harmonies. You hear some changes. You're like, "Oh, this reminds me of how jazz has influenced other music around Africa." You can detect these kinds of things, where they are incorporating jazz ideas into their composition. Then all of a sudden, this record comes out. It's like, "Whoa. This could have been recorded by Rudy Van Gilder in New Jersey. This sounds like it could have come straight from the Blue Note catalog." How is this possible?

C.M: Well, I think it wasn't a large constituency of people. But Epistles tells you, right? There were people who were really called to the music. It was very much a vocational thing. People were listening to recordings. In the late '50s, John Mehegan came into South Africa. I think he seems to have had quite an influence on some musicians, I think Hugh Masekela in particular. Abdullah – the newspaper reports are that he was more dismissive of John Mehegan, but really because he was trying to find a musical language that was local, that they could claim as their own, a jazz language borrowing from the principles of jazz with the archive of the sound of whatever had come to South Africa in recordings, largely because musicians did not travel. Duke Ellington, for example, was apparently invited to South Africa to do one of those democracy tours. He turned it down because he would have to perform before segregated audiences. Apparently he told Abdullah that, since he wouldn't travel in the south because of segregation, he wasn't going to come to South Africa.

S.R: Well, on that note, I think that's interesting, because Duke Ellington is also quoted saying that he is from the old school and he is not necessarily against African-Americans playing in front of segregated audiences in America. So maybe the concept of him playing a segregated theater in Africa was almost more bothersome to him. He made that very controversial. I don't know what year it was. But in the late '50s and '60s he made that comment in a black newspaper in the United States. So how do you explain those two views?

C.M: I can't speak for Ellington obviously. But there are some interesting things. This was the cultural boycott in South Africa, the same issue. Should we really cut off all access to the outside, to South African musicians and what's happening to South African music? Who are we punishing but black musicians themselves? It's full of contradictions. You had to have a boycott. But really, in principle, you don't want to cut off the life source. So probably with Ellington, he's confronting the same kind of dilemma. On the one hand you are saying, "I cannot be part of that. I'm not going to travel all the way to South Africa." Maybe he didn't know that there were large jazz communities, who were passionately in love with his music and people were. Duke Ellington was the epitome of great jazz arranging, because he arranged for individual musicians, very much. Chris McGregor of Brotherhood of Breath and The Blue Notes and Abdullah, both modeled themselves on Ellington. So perhaps Ellington just didn't really realize the level of passion that there was for his music when he was invited. The interesting thing is, just after he recorded with the South Africans in Paris in 1963, which is another story, he embarked on democracy tours for the American government. It was within about six months or a year or something. So it's possible he only began to realize there was in fact a passionate community of people that it wouldn't just be white people in the audience. Maybe that was some anxiety. Who will really be there? Will people have access? Who will know the music? Maybe there was even a lack of understanding of that there could be a modern Africa. There is a lot of misinformation and lack of knowledge people have. I'm not saying Duke Ellington was that way. But it's possible that there wasn't enough information given. If it was all negotiated with a white government, that's a little different too I think.

Duke Ellington

S.R: Now, this record – John Mehegan is American, right?

C.M: Yes. He's a guitarist.

S.R: He is a scholar too. He has written things. Do you think this record would have occurred without John? Were these musicians playing this kind of music without him or did it actually require an American curating the project?

C.M: Well, the music was happening. There's no doubt about it. Would the recording have happened without the intervention of a white American inside the Johannesburg recording studios? Maybe he did broker the deal a little bit. But the music was certainly happening. I think that's really what Abdullah's statement was. He said, "We don't need John Mehegan. Maybe we need him in the end to get us into the studio." But I think that in fact Abdullah was in pretty good relationship with – he seems to have been able to get into the SABC, even in the '60s and the '70s. On the trips that he came home he was able to get in. Possibly it was John Mehegan who brokered the deal, who went into the studio and said, "Look, these are really fine musicians. They could be equal to anybody in the United States." That is the kind of promotional talk that black South Africans and colored South Africans needed, some sort of validation from the outside.

S.R: For me, it's still hard to comprehend how this recording was made and why the musicians were playing on such a high level. Yes, I understand films were coming in there. They were getting recordings through the radio. But in America, before jazz was even institutionalized and you could learn about jazz harmony and complex time signatures and whatever, you at least had Art Blakey, the school of Art Blakey. You had the scene that was teaching each other. You had Dizzy Gillespie at Men's Playhouse writing out chord changes. So how is it that these Africans, that really don't have any outside connection to the world like you said, do not travel, only have access to culture via filtered film and radio, all of a sudden can make this band and it sounds so convincing that it could have been recorded here by the greatest American players? How do you explain that?

C.M: I would say that the key is this. These were musicians who were playing all the time. They were playing in many different contexts, engaged there. This is what Abdullah says all the time – "I heard music from all over the world. I heard it." It was in the Townships. Tem Hawker is the perfect example. He was in the South African Navy. He traveled the world. He picked up recordings everywhere he went. The other thing was there were African American sailors, who came into Cape Town and played at a club called The Navigator's Den, which should tell you something. That's actually where Abdullah got his nickname 'dollar brand', because he was always hanging out with African-American sailors or American sailors at The Navigator's Den in fact. This is certainly the story that goes around. So they used to call him 'dollar', because he seemed to be so associated always with Americans. That's where they got the recordings that were circulating at the time. So even if they weren't coming into white stores or going on the white-controlled radio, they were able to access this material in different kinds of ways. So the issue of Cape Town in particular being a port city is very crucial. There is a very large Marine base in Cape Town too. It's halfway between the East and the West as it were, which is why it was originally colonized anyway. So people were engaged in that way. But at this time, Abdullah was wood-shedding heavily. He was not doing anything but honing his craft and developing his skills. He was listening very closely to this music and then drawing on the resources. Sathima, the singer and his musical partner for life, says Cape Town was a musical city. There was music everywhere. You could hear things. Certainly those are her diasporic memories of the city. When there were slaves that had orchestras, these were people with very, very developed, orally transmitted musical skills. They were the finest of musicians. They played for the wealthiest of Europeans in South Africa, with the quite colored string bands actually is what they were in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Then the other thing that really helped people to develop the sense of timing and self-discipline as musicians, was a lot of these musicians had been trained in the First and Second World War. People of color and black South Africans were not allowed to pick up arms. But they could be entertainers. So a number, several hundred musicians I think or South Africans, went into the military and went up to North Africa in particular, but traveled quite a bit of the world playing jazz, dance band music and that kind of thing. So they got the skills that they needed perhaps outside of the country. Then they came back and taught the local people. So the colored community in Cape Town remember the dance band musicians, the jazz musicians being trained by these people, who have got this invaluable experience actually through the First and Second World Wars.

S.R: What you are also saying is that the infrastructure and the history is there, more so than most other cities on the continent, with being a port city and the influx of people from all over the world and the amount of money and work that was filtered and funneled through there. Like you said, you probably didn't have so many Africans learning classical instruments either, in any other place in the world as well, right? So all of this came together.

C.M: I don't know how many people were actually learning classical instruments. But the big impact really came from the Salvation Army, who provided instruments. So it was through marching bands that people also got brass instruments. I'm sure it's the same story in this country. But certainly the Salvation Army is key in having provided a number of the jazz musicians who went to universities in the 1980s. When I was teaching at the University of KwaZulu Natal, people would write their personal narratives. The impact of the Salvation Army in KwaZulu Natal was extraordinary to me in terms of providing brass instruments and some kind of training. So, in Soweto for example, Sibongile Khumalo, the jazz singer and opera singer now, her father had an orchestra going. He was the conductor of an orchestra. So she learned classical violin when she was growing up in the '50s and '60s. So there were these isolated places. But then Jimmy Adams recalls that in fact he saw a magazine or on the back of some sheet music perhaps that there was what he called The American School of Music. You could learn how to do jazz arranging through a correspondence course. He said he wrote away for it. They sent him the stuff. But he never paid them and he laughed. He said, "To this day I haven't paid what I owe." But whatever. What he did was teach himself. There is an enormous kind of 'I can do it'. South Africans, I have to say, are people who very much strongly believe that they can do things. They dream big. Sometimes it fails. But really they are an entrepreneurial kind of people. People want to make it somewhere and people do have a sense that there is a world out there. It didn't matter what apartheid did. People still had a sense that there was a world out there and they knew that they didn't have access to it. It wasn't that they sensed that the world was adequate to themselves. There is that image of the map of New York City as being the world, because people believe that that is the beginning and end of their world. South Africans aren't really like that. There's a very strong sense that there is a world beyond our culture, almost to a fault that you feel like you don't have what you need. It's lacking in some kind of way. I think that has shifted in the last 10 years. But that's certainly how it was in the '60s, '70s and '80s.

S.R: Interesting. Looking at the specific selections here, first of all, who are these musicians and what happened to them in the history? These are, obviously, pretty big names and some of them went on to do big and great things. Some stayed, some left, but who are the musicians and how did the history of South Africa and the political change that occurred affect all of the musicians that were on this one session? It's remarkable they only recorded once before they all left.

C.M.: This is Abdullah Ibrahim, who used to be Adolph Johannes Brand, Hugh Masekela, Kippie Moeketsi, Jonas Gwangwa and then John Hegan.

Jonas Gwanga is a trombone player. He's still around, but he left the country. So did Hugh Masekela, so did Abdullah Ibrahim. In the end, everybody had to leave. It wasn't that people went into quite exile initially; ultimately it became exile because their passports were revoked and their citizenship was revoked in some kind of sense by the apartheid government because they spoke out against apartheid.

The only person who didn't leave – well, he did leave initially – was Kippie Moeketsi, who's really known as South Africa's Charlie Parker. There's some writing about whether this is legitimate or just methologized but, really, if you talk to Abdullah Ibrahim he will say – they all will say to you Kippie Moeketsi was the kind of godfather – certainly of saxophone playing – but of modern jazz in a South African way. He really led people into new ways of thinking.

There were musicians who dismissed him completely, like, I think, Henry February thought he was too out there, there was too much ad-libbing, too much improvisation. And Jimmy Adams. The music was too fast, all that bop stuff was too much and, really, it couldn't be kind of processed in a very gentle way, [laughs] or however you want to think about it.

But Hugh Masekela, of course, he left in the late '50s. He got a scholarship to study at the Manhattan School of Music. He and Murray McKever were together New York. They were very much helped by Harry Belafonte and then Hugh moved around a lot. He lived in Batswana for a while, he went to California and he went in a kind of slightly different, perhaps you want to say almost more of an Afro pop/jazzy kind of domain.

Kippie Moeketsi died of alcohol abuse, basically, in the 1970s, very, very sad and very poor. Just a really brilliant but tortured musician. So, in many ways, like Charlie Parker.

S.R: Now, he had his saxophone actually taken away from him at one point and it was when the law got much more oppressive in the early '60s. For the typical jazz musician, what were the obstacles that they had to deal with once these new laws were starting to pass in the late '50s and early '60s?

C.M: At a very basic level, in 1963, they brought in a law on entertainment where you couldn't have interracial gatherings, period. Well, that's going to kill jazz, the progressive jazz. It's not going to kill the dance band music that's happening in a quite colored area, which is part of group areas. All of the colored people in one area, all of the Sutu people in one, all the Atswana people in one, all the Zulus in another and, really, that's how they did it. They even built the township of Soweto in these kinds of ethnically divided-up communities so that people couldn't, even within a particular racial group, communicate with each other. So, black South Africans weren't all naturally united. They were naturally divided. That's certainly how the apartheid regime –

So, it was very difficult. If you had a band that was racially mixed, you couldn't operate. You couldn't move from one area to another. If you wanted to have black people be in a white area, you had to have a special permit to move from one area to the next.

The other issue becomes an issue of noise. So, this is the interesting thing – it's not a jazz issue, but at Amir with Joseph Shabalala, why do they have that soft kind of dancing that never stamps their feet, which is real Inglomu, kind of Zulu dancing? Because you had to be quiet. If you attracted the attention of the police, your gig got closed down overnight or you got arrested, or whatever.

Then the other thing was the issue of passes. You could only be in the urban areas if you had been employed for – I can't remember – the last 10 years or something. Well, no musician ever gets that kind of length of employment. It was impossible. You really just couldn't survive.

Then, if the security or police got wind of the fact there was going to be an event with an interracial group, they would come in. They would shut it down. They would put people in jail. There are all kinds of stories about musicians who had to play for the police to prove that they are real musicians, that they can play the instruments and they hadn't stolen the instruments.

This is the other issue: If you carried an instrument and you were black, it was assumed that you were a thief. It really became impossible. Then, in the mixed clubs that were in Cape Town, for example, they would send in undercover white people and they would fraternize with the women of color. Basically, they were sent in as spies and, the next day, the place would be shut down. It was ugly.

S.R: For people that know about apartheid more in a vague sense – I'd say probably the majority of Americans know about apartheid, that it's about separation, but they don't know really how it works. It's a little more complicated than that. If you can, in your own way, break down apartheid and how it applied specifically to South Africa, obviously; I don't think there's any other model, really, out there other than South Africa. But, break it down and we'll start there. Just explain it for our audience.

C.M: I think one of the ways in which apartheid is different from segregation in this country is it's not just the obvious thing that it was legalized racial segregation and, at times, very brutal and oppressive, [but] it played also a lot on the ideas of cultural and language difference.

In this country, basically in the United States, most people speak English. South Africa has, now, 11 official languages. English is one. Then Afrikaans, which is a kind of mix from Dutch and is actually a very interesting language because it came with slaves. It developed out of the context of slavery and those slaves were not just from Africa; they came, largely, from the east from Indonesia and Malaysia. Many of them were Muslim, so actually Afrikaans is a language that was first written down in Arabic. [laughs] So, that already tells you that there's a very complicated history but it was the language, then, that was claimed by white people of Dutch descent as their own language. Then, of course, it was imposed on black South Africans for education in the '70s.

So, with the 11 official languages, you can easily justify separating out people by saying, "Everybody must have rights to their own language and culture." And then you say, "That's why all the Zulu people must live in one place, the Sutu people must live in another."

The problem was that, by the time they came to this kind of legislation in the 1950s, there had already been 70 or 80 years of labor migration from rural areas into the urban areas. There were large, ethnically-mixed [areas] – not necessarily racially, though there were some racially mixed areas. So, people had been in urban areas, they had been in contact with each other. Some people had never lived in a rural area before but they created what they called these homelands, or Bantustans, that were defined by language and culture.

So, if you were Zulu, you had to live in a Zulu homeland, or Bantustan. If you were Sisutu, you had to live in a Sisutu language and culture area. People were sent back to these places if they didn't have work in the urban areas. Life became, at a certain level, absolutely impossible for a lot of people.

Then, with the crisis of labor migration, which was necessary when gold, diamond and minerals were discovered in the late 19th century in South Africa, black South Africans were kind of coerced into going to find work. Initially, they were coerced because they had to pay taxes in the form of money and they didn't have access to cash, so they had to go and earn it. That process denatured the rural areas of able-bodied young men, essentially, is what it did. That really transformed the rural areas, too.

So, it's in that sense that these are very complex processes. One is the huge level of difference that there is in the country and ways in which that was manipulated to, in a sense, control individual groups of people. Then, there is the issue of labor migration, which is the thing of rural to urban and back again, and what that did to communities of people.

S.R: District Six is one and Sophiatown is another community where black Africans own property and, in some cases, were flourishing. The comparison is often with the Harlem Renaissance. There was a lot of activity and cultural vibrancy in these areas, and these areas were completely demolished, right?

C.M: They weren't only black areas. District Six was a very mixed area. You see, it's an interesting thing; I think the parallels are racially here in this country. People say that when Frank Sinatra came into the popular music scene, he was seen to be too dark-skinned. This is what I've heard. Same thing in South Africa. So, those kinds of Southern Europeans who were a little bit more dark-skinned people of Jewish descent, too, lived in District Six. So, it was a very mixed area and it became more and more mixed through the 20th century. It became more and more what we call colored.

People say that we have romanticized too much. I'm not saying Sophiatown but certainly District Six because, in fact, by the time the government decided to clear it out, it had become kind of run down. There are people who have different opinions about it, but there's no doubt about it that District Six was a very vibrant, culturally interesting, linguistically interesting and musically very, very amazing center, as was Cato Manor in Durban and Sophiatown in Johannesburg.

These were very vibrant places and it really was that they were also places where jazz could develop because people were doing it for the love of it. You didn't do it for the money; there was no money. You were poor, and there was lots of music. If somebody had a gramophone playing, you could hear it because everybody was living on top of each other. This is really what, I think, Abdullah Ibrahim's talking about, too, is that if you grew up in a place like Kensington or one of these townships in South Africa, you heard so much different music. There was church music, all different kinds of religious beliefs. All this stuff was going into your memory and building your sense of what it was to be living in South Africa, in a black township in particular. Lots of language mixing, lots of musical mixing.

And, of course, then the mixing became the problem for the apartheid government. It was mixing. In fact, some have argued that Group Areas Act, which was to separate people, and a lot of the apartheid legislation was put in place to get rid of the presence of mixed-race people, to get rid of the evidence of miscegenation that had been a natural process in South Africa for 300 years.

S.R: Wow. So, is apartheid the second-worst thing that happened to Africans other than slavery? Would you say that? How would you describe apartheid? In some sense, it's so modern. It almost happened yesterday in a way.

C.M: The relationship between apartheid and slavery is an interesting one, and it brings us back to this thinking about jazz. Satima, the singer that I've worked with a lot, she says that the reason why jazz happened in South Africa and not in other places on the African continent is because – and this is how she says it – Obviously, slavery happened mostly in West Africa but from central and east Africa, as well, to some extent. But it was apartheid that happened in South Africa. She says jazz was the sort of outcome of that process because, while South Africans didn't get ripped away from their continent, their continent was ripped away from them.

So, the one is a story of slavery, the other, of course, is colonialism and the extreme forms of colonialism, which were these desperate efforts. As the rest of Africa was becoming independent from European control, South Africa became more and more suppressed by it.

S.R: And how did the Dutch, or the apartheid government specifically, view jazz?

C.M: Anything that gave you a sense of individual freedom, of course, was not going to be seen to be a good thing. I think if you could keep things under control, that would be OK, but I can't really speak for the government as a whole except where it would have been manifested would be the radio programming by the South African Broadcasting Corporation. So, every now and then, there would be some sort of effort to put on a jazz show at 11 at night or at midnight for a few specialized late-night listeners. But, for the most part, this didn't really work.

There was also heavy control of lyrics, so the blues weren't played very much. It just wasn't seen to be appropriate because it was too sexual, too black and sexual. [laughs] So, that kind of music wouldn't have been played. It was better to have instrumental music that was kind of clean, defined and under control.

But the interesting thing, of course, is that place of the Netherlands now. People of Dutch descent now who are very, very big into free jazz and into their own versions of what has come out of the American jazz scene. I don't want to speak for the Dutch specifically but definitely control of the population was the issue under apartheid.

S.R: You alluded to it with what you said before: Maybe the biggest tragedy of all of this is that all the musicians left. What could have South Africa's jazz scene been like, say, if the history was different around 1960 when 16 other African nations became independent with their governments? What could have been?

C.M: It's hard to really speculate because also fashions come and go. It may not have been a much larger community than it was, say, in the late 1950s but it would have been – there is some sense in which South African jazz is much more known now because musicians left.

The trouble is that South Africans who stayed behind feel that those who left profited off the suffering and, in a sense, had an unfair advantage because their music got recorded. But I think that when you look a little deeper, when you hear the stories of people like Johnny Dyani, the bass player, and Louis Moholo, the people who left – maybe it was easy for the couple of people who got taken under the wing of Harry Belafonte. But even Duke Ellington was not always treated that well even himself, although he was a very generous individual to the South Africans that came into contact with him.

So, I don't know that we can say what if. Now, what is interesting is how people responded to the kind of sudden clamping down and loss of these very vibrant communities and lots of really interesting music that was happening. In the 1980s, for example, universities started to say, "We have a responsibility now to institutionalize this music."

So, you have Dave Brubeck, and his son, Darius Brubeck, going to the University of KwaZulu-Natal and the University of Cape Town opening up a jazz program. The University of [Unintelligible] has a jazz program now. Rhodes University in Grahamstown has one.

So, with all these now centers of jazz education, who's to know if there hadn't been some sense of the pressure to acknowledge what happened in the '50s and early '60s, maybe things would have gone in a very different direction anyway and maybe there wouldn't have even been as much jazz as there is now. There's been the capacity for people to return to something. I'm not saying what happened under apartheid was a good thing. I'm not saying that at all. I'm saying it's hard to speculate on what would have happened.

S.R: But you're making the case that the musicians in exile or the jazz in exile could have, in fact, even helped develop the sound of South Africa.

C.M: A little, yeah. I also think of the musicians who came into contact with – I think especially the European scene. When the Blue Notes arrived in Europe, it wasn't easy for these guys. When Abdulla brought over his trio, The Dollar Brand Trio – Makaya Ntshoko and Johnny Gertze – they came into contact with and started to listen to a lot of the free musicians – Albert Ayler and a lot of those guys who were not being well treated in the United States. People were not really understanding what they were doing, and they were coming to Europe. They were going to Copenhagen, they were going to Paris and South Africans came into contact [with them].

There was actually quite an extraordinary international community of musicians. The interesting thing for me, too, is that when these musicians went to Europe, by all accounts, they didn't seek out just black musicians. They had a vision of a non-racial jazz-producing community. They wanted to play with whoever was playing interesting music, whoever had the kind of right spirit about them. And, for a lot of these musicians who were not musically literate, meaning that they couldn't read music, they hadn't been trained to do it, they wanted to play with the musicians who were willing to listen and willing to experiment with the sounds that they brought to the table, too.

I'm quite sure that some of the music that was produced in sort of exile, in Diaspora even, in Europe, there was some really extraordinary stuff. I wish South Africans knew more of what it was. I wish it was more available now in South Africa. But there are musicians now and communities of people in South Africa now that listen to that free music, the free stuff of the '60s and '70s as it came out of the United States. They still are listening today to that stuff. So, there's still some kind of extraordinary sense of the music breaking through boundaries and people are still responding to that. I think that's the greatness of the international jazz community.

Perhaps if South Africans had just stayed in South Africa, those kinds of bridges wouldn't have been built. We wouldn't have been open and exposed to that kind of world in quite the same way because the mass media is not bringing it in. It is individual carriers of the traditions that have had to really go back and forth. I think it has been done through human transmission more. And, of course, recordings but you've had to have people really exposing communities to this music, so I don't know. We can always be a little bit more optimistic when we're free to be optimistic. We couldn't have been optimistic like this in the '70s because you it just felt like it was just oppression all the time.

S.R: Quickly, just one or two sentences: What are the other sounds that you heard in the late '50s in other styles of music that you may have heard on the radio besides jazz? And then how much of the segment of the population would you say, per capita, were people into the music of all the different sounds that were going on?

C.M: A lot of the music that people engaged with was religious music. There's a lot of that. In the late '50s, you would have heard a lot of commercial music. Through the early '50s, it would have been the wartime music: [Unintelligible] the British people, the Americans, a lot of Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, the kind of people who were sort of socially acceptable and whose lyrics were clean and upright.

Elvis Presley was banned. He was too risqué, I think, for the apartheid government. You would have heard a lot of European classical music, not the heavy stuff, though. It would have been known as light music, so light classical music.

If you had been a person who spoke one of the indigenous languages, in the 1960s, Bantu Radio started to target its cultural and language groups. So, if you were a person who spoke those languages, you also then started to listen only to that kind of music. Or, in the 1960s, you would have started to listen to this kind of multi-ethnic, studio-produced Makongo. You would have had a little bit of mascana, which is kind of a modern-version Zulu guitar sometimes played with a backup group; that would be in the '60s and '70s.

There was some [Unintelligible] but a lot of religious music, some of it quite traditional sounding. And Afrikaans [Unintelligible], which was small ensembles. Really, it was kind of for dancing, as well – two-steps and waltzes, those kinds of things.

S.R: So, it's almost like the so-called jazz craze was more of an idea, a metaphor, rather than a real jazz craze? People weren't, like, crazy over swing as much as they were crazy over gangsters and alcohol?

C.M: I think what you're talking about, what people would have heard on the media, is different from what was happening live. I think there is a gap between the two. For certain communities of people, for modern Africans, people in the townships, you wouldn't necessarily have heard the music on the radio that you heard live. People would buy recordings.

I think recordings were the sort of anomaly for a long time, certainly into mid-1960s. In fact, I can tell you that I read a magazine that was produced by a small group of white guys in the mid-1950s called Bandstand Magazine. It's very interesting. It's sort of modeled on Melody Maker from Britain and Down Beat in the U.S. In fact, the people who were writing the articles for that were in contact with the Down Beat people. There's a little note that says the president of Décor Records arrived from America and he says that South Africans are the largest record-buying public outside of the United States for Décor Records.

That just gives you some idea of where people were getting their music from, how important imported music was to them and I think it's this attitude of always that "it's better on the outside and we're just humble South Africans. We aren't the master; we are the copy." I think there was a lot of that kind of feeling. And also still kind of enjoying a lot of enthusiasm for what was happening locally but always thinking that the better was happening outside. So, people bought recordings.

S.R: And Louis Armstrong did visit Zimbabwe in 1954, right?

C.M: He went to Zimbabwe and Ghana, so he was just north of South Africa. He didn't come into South Africa, but there were South Africans who traveled up to Harare to meet him. In fact, there was a guy, Ben "Satchmo" Singer, Satchmo being Satchmo like Louis Armstrong. He was the South African sound-alike of Louis Armstrong. He met him. First, he went to Zimbabwe and met there, and then he traveled to London and met him there. And, of course, Louis Armstrong gave a trumpet to Hugh Masekela via his wife. So, there are lots of these lovely kinds of connections but it's all one-on-one and you have to travel a long way.

Let me just explain to you something about recording culture. There's this lovely quote by Hugh Masekela. He says that when Clifford Brown died, he was so passionate about Clifford Brown's music, he sobbed his eyes and his heart out to the point that his grandmother really had to kind of console him as if his closest relative had died. He'd never met him but he knew his music so intimately from having listened repeatedly.

And, of course, people were really passionate about it. They listened together; it wasn't individual listening and people passed recordings around. You would share them. Some of the musicians I've interviewed said that they would walk for miles because they heard somebody 10 miles away had just bought a recording and they wanted to hear it. You didn't even know the person, you'd just arrive at their house and say, "I need to listen." So, there was a kind of open-door policy, I guess is how you would say it.

And Satima talks about this Swiss graphic design person who was a jazz collector in Cape Town. His name was Paul Meyer and she said she took all kinds of risks against the apartheid rules in order to hear jazz. Particularly, that was when she first hear the sound of Billie Holiday. The guy thought she was interested in him romantically, but she was not. But she broke apartheid law to go and listen. She was there one night as his place in Camps Bay, which is a very elite, white area. As a woman of color, she could only go there if she was going to be a house maid, like a maid in the home, and she arrived as sort of an equal citizen and there was a knock on the door. She thought it was the police coming to get her. She was terrified. In fact, it was Abdullah but that was the fear you lived in in order to hear the music.

S.R: Why don't we just choose a few pieces of music? Why don't we go with Mannenburg just because it's so representative of so many cultures there. Just set it up for us. Why is this piece of music important?

C.M: Mannenburg is controversial. Everything in South Africa's always controversial. The story is that it was in the mid-1970s, sort of around the time of the Soweto Uprising but in Cape Town.

S.R: Which is what? Very briefly, what is the Soweto Uprising?

C.M: It was Johannesburg. This was the June 16 uprising of school children against the government saying that they had to be educated in Afrikaans. They said this is not our home language. We have mother tongues and so they protested. Of course, the security forces came in and just killed children, and this was kind of mass mediated. The images of children dying was mass mediated around the world.

So, at about this time – and it was the turning point in the anti-apartheid struggle. I think everybody historically knows that this was the moment. When children rose up and the security forces just opened fire on them, the world was outraged and so were South Africans. So, this was about that time Abdullah Ibrahim was back in South Africa and his version is, apparently, he went over to a piano and he was playing.

They were jamming around with him and Basil Coetzee and maybe Robbie Jansen and a few others and out of that kind of jam session, it's a very [Paul Simon-ish] conversation [laughs] came this tune "Mannenberg is where it's happening." It was recorded, I think, by Rashid Vally and, surprisingly, became extremely popular. This is the story.

Now, Abdullah, I think – the issues over copyright is what the controversy is but it did become a kind of unofficial anthem of the anti-apartheid struggle. Certainly, in the Cape area, this became a sort of rallying cry. In fact, I was a student at NYU in the late 1980s. Going into what was Sweet Basil became Sweet Rhythm, now shut down, but you'd go into there and Abdullah was playing. There would be a bunch of South African ex-patriots and he would just start the first three or four notes of Mannenburg and, boy, you just – you almost wept with the joy and the sorrow. The mixed emotions were so great every time he played this tune. It was just really amazing. It very much symbolized something of what it meant to be South African.

S.R: And there are strains from many different ethnic groups in the piece, too, right?

C.M: Well, it's a kind of Morabi, rolling bass thing. Morabi was this kind of speak-easy, drinking, working-class culture of the '20s and '30s, which is basically the blues of South African jazz history. It had this repeating bass line. The melodies of Morabi were borrowed from church hymns, anything – traditional songs. It's very hybrid, as it is with all South African music, really. You'd freely borrow from this and that and you'd create something new. It's kind of a melting pot all of the time, but it's not really just melting pot. It's that you're patching something together to create something distinctively South African.

I think the joy of it is that so many people can hear something in it that feels familiar. So, there's Morabi, which is drinking culture, and then it sort of feels like a church hymn a little bit. [laughs] So, the religious people can fit into that and then there's something about just the repeating root-movement of moving, say, from a C to a D. It's that kind of movement, which goes back to traditional musical bow playing from the Nguni people. There's a little bit of something for everybody but belonging to nobody, perhaps, except maybe Abdullah Ibrahim [laughs] and Basil Coetzee.

S.R: Awesome. That's great. And why, also, did African Space Program really speak to you and speak to the time?

C.M: This is a recording that the African Space Program and there were a couple of others – Good News from Africa. They were recorded in the 1970s. I love this music, I have to tell you. Again, probably for the same reason as Mannenburg: there's something in it that sounds familiar. The piece that I love the most is actually from Good News from Africa, which is Johnny Dyani, the bass player, and Abdulla Ibrahim together experimenting on a program of African space.

Now, of course, when we think space, you think Sun Ra and there is some dimension of Abdullah I think that is very Sun Ra-ish. He's more controlled maybe than Sun Ra, but I don't know because I think Sun Ra was kind of a little bit that way himself. So, it's looking for some kind of space for Africa in a kind of space Mars intergalactic sort of way. But the piece that I love most is Ntsikana's Bell. Ntsikana's was a [Unintelligible] prophet [unintelligible] who had been converted to Christianity, but he was one of the first prophets out of that mission encounter and he composed a number of hymns.

One of them is this beautiful, very slow song called Ntsikana's Bell. I actually first heard it when I was on a mission station looking for African music one Easter when I was an undergraduate in the Eastern Cape, and I heard it played on marimbas and sung all weekend. It was absolutely beautiful. And then here I heard it. it's very much part of [unintelligible] oral tradition now because of the long, strong religious roots in the Eastern Cape.

But there is Johnny Dyani singing in [unintelligible], Abdullah singing in Arabic because he'd converted to Islam very recently and just these natural voices just doing the most beautiful stuff in a very jazz, improvised, free sort of way. It's so distinctly in Eastern Cape. It's so not American and yet it's so deeply in the spirit of what jazz is about. It's just the most moving. It's so about the new and the old African Diaspora but, certainly, the new African – of Africans who've come out of a different part of African than slaves did but who have suffered nonetheless and, in a sense, it creates the bridge between the old and the new. It's really beautiful and compelling.

S.R: Wonderful. Now, a lot of the jazz music turned very electronic in the '70s, almost more funk oriented.

C.M: Yeah.

S.R: Is that just because the acoustic instruments just became less fashionable? This one piece of music, Philip Malela – you know that piece?

C.M: No, I don't know [Unintelligible ]. Actually, David Coplan has written quite a bit about this in the 1970s. A lot of what happened in South Africa, I think it was really an influence of Herbie Hancock [laughs] and the kind of funk stuff that was happening in the U.S.

S.R: Well, that song sounds exactly like Headhunters, like it's a literal rip-off.

C.M: Oh, it is? [laughs] That's interesting.

S.R: And David Coplan doesn't even mention that, but it sounds the same.

C.M: This is a British production and I just bought this CD online. I think I hadn't even opened it when I gave it to you. But this would have, again, been the kind of influx of recordings. This is the interesting thing, actually, about apartheid: Lots of things were banned, especially anything written. There are actually some quite tragic but hilarious stories you can read of white South African journalists who were visited by the security forces.

There are some really funny things that you can read about now, people's memories of what these moments were. As scary and intimidating and terrible as they were, they were also kind of ridiculous of these fairly uneducated security force people coming in and looking at books and saying, "Who's Karl Marx?" and "Are we looking for things Russian?" There would be really innocent things but, because they were Russian and supposedly communist and of the Soviet Union, it had to be dangerous in some way.

C.M: So, I think the interesting thing with recordings is that there was some measure of control over what came in, but there was also a lot that slipped under. People brought things across the borders in suitcases and stuff.

S.R: But electric Herbie Hancock was big in South Africa?

C.M: Well, he must have been, yeah. So, what I'm saying to you is that's how music would have come in. Even though it was African American and would have been seen to be maybe something perverse, too modern, definitely there was quite a large rock movement in the black community in South Africa in the '70s. It's not my area of expertise, I have to tell you. [laughs]

S.R: Because that piece is so funny. It's almost like a complete rip-off of the tune. I'm surprise David Coplan didn't even mention it. How can you write about this and say this is not Headhunters? It doesn't even make any sense to me because [laughs] the drum accents are the same, the licks are the same...

C.M: I don't know why he didn't write about it, but the other thing is there's an enormous amount of music that is produced in South Africa under license. So, there was a three-CD compilation produced in the early '90s by Gallo Records, the main commercial outfit, saying "when local was lecca," meaning cool, hip. And you listen to this music and there's nothing local except it's South African singers doing it. So, it's being sung under license because it's just too expensive to produce original material for a very small marketplace.

I would imagine that the black rock consumer base wasn't that huge. It might have been it wasn't considered to be huge by the people who would have recorded the music, so it's possible that they've just licensed it a bit like Wimoweh and Oombabeh, In the Jungle. It got recorded under a different name but they paid for the licensing for it. Do you see what I'm saying?

That comes back to that issue of you always think that the best is happening somewhere else and to make it local is to just simply put it in a black voice or in a black language. Glenn Miller's In the Mood was sung in Zulu. That made it sound very local because the language is different, the sound is different and the intonation is different. The instrumentation and the arrangements are exact copies but the voice is what makes it local.

S.R: Is there a recording of that?

C.M: Yeah, Chris Ballentine has it. You can ask him.

S.R: I would love to hear that. [laughs] That's really hip.

C.M: Yeah, it is, but you'd have to get the issues of copyright. He probably owns the copyright of the recordings now.

S.R: I'd love to hear that. That's crazy.

C.M: Yeah, I have it somewhere. [sings]

S.R: Are you serious?

C.M: Yeah, this was still part of the 1940s and 1950s. Yeah, '47.

S.R: It was recorded in the '40s, too?

C.M: Yeah, soon after. Stuff would come out and that's why it was all cleaned up. What vernacularized and indigenized this was language. That is the thing that makes it feel local; you sing it in the local language. There were the African Ink Spots and what made them African is not the jazz arrangements or the instrumental arrangements, but the voice. The voice is the key in South African music.