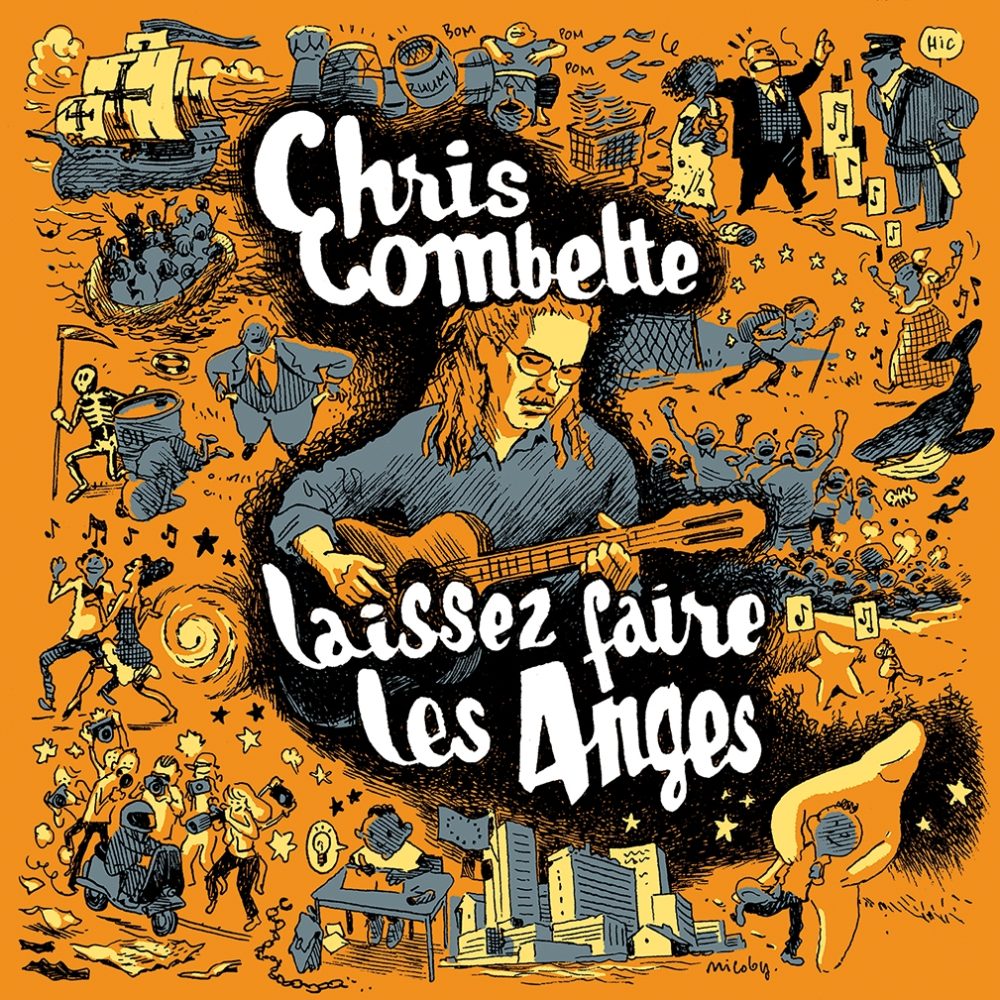

A native of French Guiana and raised in Martinique, Chris Combette has done a lot to introduce the musical traditions of the Caribbean to listeners in France. Self-taught on bass and guitar, he played with Martinique-based musicians such as Tony Chasseur and Rastafarian banjo player, Kali, before further developing his own style with the popular zouk band Silence. Finishing his education while in Paris, Combette supported his musical career as a math teacher in France before he left teaching in the mid-1990s to focus on his music. His debut album Plein Sud, released in 1995, garnered him five nominations and a songwriter of the year award from SACEM (French ASCAP). The title video clip from his second album Salambo was a finalist in the Radio France International Video Festival in 1997. The following year he performed “Lonbraj an Pyé Mango,” with Kassav’ vocalist Jocelyn Beroard, that was a hit from the compilation album Duos du Soleil. His third album, 2003’s La Danse de Flore, saw him revisiting some reggae influences and produced “Babylon Buildings” which made it onto Putumayo’s World Reggae compilation album. A few years went by before the release of his fourth album, the more politically engaged Les Enfants de Gorée in 2011 which produced the popular video “Kon Oun Lotomat."

I first met Chris Combette in 1998 at the world music club SOB’s in New York right after he had opened for Martinique percussionist Marcé and his group Toumpak as part of his North American debut tour. We struck up a conversation and I was immediately impressed by his openness and the full sound he projected playing alone with only his guitar and vocals. Our paths would cross again in 2004 in a small nightclub at Montreal’s Festival Nuits d’Afrique which I was covering for The Beat magazine. We’ve kept in touch ever since, and I was pleased to contact him for the following interview that took place on the heels of his latest album, Laissez Faire les Anges, this past November.

Brian Dring: It would be hard to discuss the recording of your latest album over the past two years without mentioning the pandemic. So how did it affect the recording process, and how is French Guiana handling it at this moment?

Chris Combette: Strangely enough, at least at the beginning of the pandemic, the lockdown didn’t change much in my life, which largely revolves around my office equipped with a home studio. I was just finishing up the writing of the album and I did not suffer immediately from the imposed restrictions; on the contrary there was something almost peaceful in the silence outside–in the midst of the impending terrible change about to come of which I was perfectly aware.

But ultimately the pandemic ended up slowing down everything. Like everyone else I began to suffer from the lack of social connection, the freedom to be able to come and go, and from the forced separation from loved ones. Neither did the music escape—several studio sessions had to be postponed because of lockdowns and repeated curfew. Rehearsals became unfeasible and concerts unthinkable. Fortunately, the musicians and I took advantage of the lull to finish the recordings. In Guyana 38 percent of the population is vaccinated and a full two thirds of the population still refuses vaccination. For the past three weeks the Omicron variant has wreaked havoc here like everywhere else, so we decided on a curfew from 8:30 p.m. to 5:00 a.m. and night life is therefore rather subdued even though authorities made the decision to have this year’s carnival. What was impacted the most was the making of the live music video to promote the album. Fortunately, I was able to work with a talented director and the video of the title track

It has been almost 10 years since the appearance of your last album, 2012's Les Enfants de Gorée. Were you living in France then and has moving back to French Guiana changed your writing perspective?

Maybe so – it’s a beautiful land and you don’t have to travel far to find yourself in the middle of the rainforest and experience all the beauty that nature has to offer: protection. But French Guiana is a version of France very different from that of the Hexagon [mainland France]. Over here there are 10,000 children who don’t attend school…

A lack of medical facilities prevents proper treatment of the sick; prices are exploding, unemployment too; so has violence become endemic with all that it generates such as discrimination against foreigners who, for some people, are the only ones at fault. I think that without really realizing it, observing the world here makes me even more pessimistic about its future. But to keep hope is to stay alive, so I hope that this pandemic will at least have the merit of provoking more introspection in each of us and, why not, maybe even more solidarity.

Does the theme of this new album reflect the way the world has changed, your own evolution since then, or both?

Both. For example "Lafòs Pwav" [lit. the strength of negative news or “pepper”] is a commentary on the new model where social networks allow everyone to express themselves and push delusional thinking and for some to become a star of a day or two with a few thousand likes. A lot of people rush into this tunnel and sometimes they come out of it badly. These same networks very often convey unverified information and fake news blurs reality and prevents an objective reading of society. When it comes to attacks on people, it is very difficult to restore the truth which circulates less quickly than sensational fake news lies. At no time in the song do I suggest a suppression of social networks however; I don’t have that authority – yet the networks remain in place and the world moves on as it has always done.

But this communication tool of social networks, which in many cases has facilitated mobilizations in the face of injustice or legitimate revolts against oppressive regimes, is different insofar as a post by an average person can technically be read globally, so everyone can talk to everyone and in real time. In "Lafòs Pwav" I took the liberty of warning young people based on facts. Yes, networks can be dangerous if the content is unfiltered.

"Laissez-faire les Anges" speaks of the good people who welcome migrants at the risk of fines. Political and ecological migration has increased particularly in recent years, and like social networks, they are participating in a change taking place in the world that for the moment has no solution.

What does the album title Laissez Faire les Anges mean to you? And is the word "anges" intended to mean angels or spirits?

It refers to the open and empathetic people who are endowed with spirit – that’s one of the album’s themes. In this song it’s about the spirit as in intelligence of the heart, the one that feeds on love, the one that understands that loving is always the bearer of life, of hope and never of destruction and death. I think that this intelligence, which is reminiscent of the beehive concept, is the only one that is worthwhile. All the others, if they are not "framed" by a benevolent vision of the collective, are sterile. Those people who carry this spirit within them, and share it with those in need are true angels. There are many of them and humanity is not dead.

My favorite song of the album is "Fatoumata" [About a young mother who gets laid off her factory job and then arrested for stealing food]. What inspired you to write the lyrics? Did you know a Fatoumata?

I don't know a Fatoumata personally but I know of hundreds, thousands, millions. There is one justice for the powerful and another for the poor. How many times have we been told that a particular politician is responsible for his actions but is not found guilty? Chlordecone [a banana pesticide] which was banned in France in 1990 continued to be spread on plantations in Martinique and Guadeloupe for another three years. Today, these territories are some of the most affected by prostate cancer in the world but there is no trial, no judgment and no conviction. If a scandal of like that can’t mobilize justice, how can we expect it for poor people who routinely suffer from similar instances of environmental racism? I wanted to bring attention to it by magnifying its size to match intention behind this kind of social planning and geographic inequalities that I have trouble understanding.

Your albums usually contain at least one song with a colonial reference, such as "Lévanjil dan Bouch” [The Gospel Truth] Do you think it's important for an artist to remind people, especially young people, of a significant historical event?

The settlers arrived with words from the gospel and they left with the riches. Unfortunately, the story doesn't end there. Even today Africa is being plundered: the CFA franc is still relevant and neo-colonization, even if it takes other forms, is an evil that continues to eat away at Africa. "Lévanjil dan Bouch" is a cry of indignation and lack of understanding and not just a reminder of history, it is the current events. If some young people who hear the song are moved by it then so much the better.

The song "Grenn Douri" [Grain of Rice] references Fort Cépérou which was built during colonial times to protect the city of Cayenne. Do the lyrics purposefully make reference to an incident that happened there?

In 2017 a huge demonstration against the high cost of living and financial insecurity brought together about 40,000 people in the streets of Cayenne. Such a mobilization had never been seen in French Guiana. All components of the Guyanese population were present in a particularly peaceful atmosphere. People came from everywhere, from small towns to large agglomerations like Kourou or Saint-Laurent du Maroni, 250 km from Cayenne. This gathering has remained very present in the collective memory and I think it will remain for a very long time. The prefecture of Cayenne, just next to Fort Cépérou, was chosen as a rallying point—quite a symbol. After this mobilization, promises were made by the government for development to be better accompanied, not all of which have been kept by the way.

What inspired the album's last cut, "Yosakoi Creole”?

I met Emanuel Brodoff for the first time in French Guiana at the Festival Transamazoniennes. Two years later he had relocated to Japan from where he reconnected with me and presented me at The Harvests of Tosa Festival which takes place in Kochi on the island of Shikoku. He wants me to come for a performance accompanied by a large troupe of dancers and asks me to write an adaptation of the famous Japanese song "Yosakoi Naruko Odori,” written by Takemasa Eisaku. "Yosakoi" is also a dance and a festival bears its name. His proposal aroused my interest so I accepted and started working on a Creole adaptation of the song. So, in March 2016, under a clear sky on the island of Shikoku, I found myself alone on stage singing with my guitar [and on a soundtrack created in my studio with additional instruments] the traditional song known to all Japanese, all while a colorful dance troupe performs a majestic choreography.

The next performance, more modest, took place in a club and while I’d never added the original Japanese version to my acoustic repertoire with just vocals and guitar, I embarked on the Creole interpretation of “Yosakoi." Although they were surprised at first, the audience sang along to the parts that they recognized – which was an energy and a joy that transported me and very deeply moved me. From that moment on, the song became part of my repertoires, much to my great joy, and to that of the Japanese. I think that the positive reaction to "Yosakoi" was a factor in my returning to Japan the following year, where I gave several concerts not only in Kochi but also in Nanto, Tokyo and Shimanto.

You had your daughter Marie singing with you on that last cut. I recall that she accompanied you with harmonies on the performance you did for Virtual Music Lounge in May 2020. What was the evolution of beginning to include her in your performance?

My daughter Marie grew up listening to my songs being created, and even if she didn’t make it her passion, she loves music and has an obvious talent for singing. So, it was quite natural for her to sing along with my songs that she already knew by heart. Much later I asked her to contribute vocals for an upcoming concert and to my surprise she agreed to overcome her natural shyness. The concert went very well despite her stage fright which, paradoxically, got an affectionate reaction from the audience. After that experience her self-confidence on stage has grown so whenever our schedules permit, I invite her on stage and, as with Lindblad Expeditions, for virtual concerts.

Finally, let's talk a bit about your musicians. Is there a core band that accompanies you on tour and in the studio? And how did you get to know the excellent keyboardist David Fackeure?

For the first time ever, I recorded in French Guiana with the musicians of my recently reformed group with Georges “Tijo” Mac on percussion, Patrick Plénet on bass and Eric Valérius on drums. I also called on musicians from France with whom I worked remotely: Ralph Lavital on guitar, Nicolas Pélage on background vocals on one song, Thierry Vaton, my long-time accomplice on the keyboard. David Fackeure recorded keyboard parts and also mixed the album. Remote recording can’t fully substitute for in-studio but, fortunately, today’s technical advances make it an option. Nevertheless, David’s availability, responsiveness, and kindness were essential for this detailed and demanding kind of work. I met David in July 2017 at the Nomade Festival in Yvetot, Normandy [France]. We quickly became friends and listening to his work I immediately knew that he would be perfect to mix the album Laissez Faire les Anges.

Related Audio Programs