Fatoumata Diawara lives in many worlds, a free soul defying the restraints that hold so many down. She fluidly moves between emotions and states of being, but her warm, radiant undercurrent never fades. She sings soaring, hopeful songs in opposition to oppression and war, and weaves together Wassoulou folk, rock and Malian pop.

Diawara was born in Côte d’Ivoire to Malian parents who lived their Malian identities strongly. Although she has never lived long in Mali, Diawara regards herself as distinctly Malian and distinctly Wassoulou. But Diawara rebelled against her parents’ restrictive expectations and secretly boarded a plane to Paris to join the world-renowned French street performance group, Royal de Luxe, the monumental masters of spectacle who brought, among other things, a 42-ton mechanical elephant and giant mechanical girl to walk city streets worldwide. She toured the world with that performance, playing the wife of the sultan who owned the elephant. She has a distinct worldliness, adventurousness and independence but also an approachable friendliness. Since music became her profession, she has collaborated with a huge range of musicians, including The Roots, Cape Verdean Mayra Andrade, and her longtime Wassoulou mentor, Oumou Sangaré. Carrying all of this richness and complexity with her, Diawara brought her music and her message to an adoring audience at Harlem’s Schomburg Center on May 4.

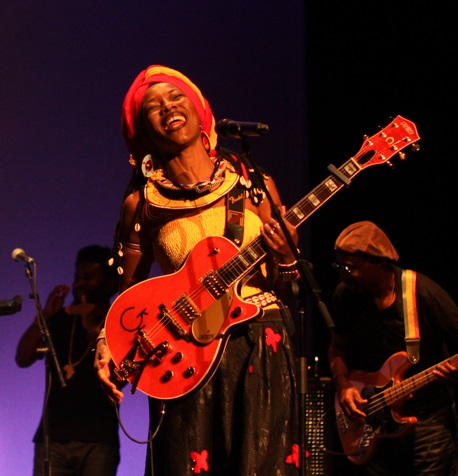

As she often does, Fatoumata stepped out onto the stage with a smile, an excellent, bright outfit, and a red and yellow headwrap. She began without pause with her song “Boloko,” a heartfelt cry to parents to stop female genital mutilation, a practice still common in West Africa. She followed this with an uplifting ode to Nelson Mandela, punctuated with ululations and seriously funky bridges. Two songs in and one could clearly feel her engagement with the struggles of the world and hope that they might be overcome. Her passion for justice and change carried through the concert, in songs about child refugees, children abandoned due to poverty, and war. She cites Mandela’s pride and powerful voice as inspiration for her vocal politics: “I am African and I can speak for myself,” she said.

Her energy is irresistible, drawing the whole audience onto her level. During the opening songs, while her headwrap is on, Diawara is laid-back and calmly funky, her voice flowing out like water or light through a window to fill a room. When the headwrap came off during one particularly raucous song, and her hair was freed to fly, her energy transformed into fire and wind. She rocks hard to a shredding guitar, blowing a whistle, spinning like a whirlwind, dancing with intense vitality. Each of her long dreadlocks wears a cowrie at its end, lending a beautiful accent to her fiery choreography. A Fela-esque breakdown inspires strong, slow, sensuous movement. It is too difficult to stay seated with Diawara on stage, so her invitation to stand up and dance was very welcome. When some of the audience started to sit down again after a song, she cried, “Are you tired?” Of course, we weren’t. “Then why are you sitting?! I came from Mali to be here! Dance!”

Ever-present on stage is her rich and heartfelt smile that overflows with joy and welcomes everybody in the room to feel the same. Diawara loves the music, she loves the movement, and she loves those who can share it with her. She is fierce and strong, with clothes the color of fire and movement to match. She is tender and caring, with a presence colored by compassion and openness. Reading YouTube comments is most often a deeply aggravating activity, but scroll down from Diawara’s videos and your heart will be lifted by the effusive warmth and affection with which her listeners write about her. It seems that her whole audience, online and off is unambiguously inspired by her effervescent good energy and her voice both mellow and fierce.

Her voice is clearly Wassoulou, likely shaped in that direction while a backing vocalist with Malian diva Oumou Sangaré. It has such easy volume and clarity, in the way that Malian djelimusow, or griottes, do. As our own Banning Eyre describes it, “her mellifluous voice rises to take on a ragged edge, moving from quiescent to fierce in a carefully modulated escalation of passion.” At two points in the night her voice inspired showers of dollar bills from audience members. Her song “Sowa” starts with Diawara offering some agile rhythmic lyrics in Arabic and Bambara, all delivered with a grin. At the Schomburg, she brought up a guest drummer whose punchy funk beats brought the already great tune to whole other level. She engaged the crowd with several call-and-response choruses, urging us to sing louder so her “ancestors in Wassoulou can hear,” and we obliged.

Awa Sangho joined Fatoumata Diawara on stage.

As an excellent surprise, during her encore Diawara called out onto the stage her friend, fellow Malian diva and Harlem resident, Awa Sangho. Their chemistry is beautiful, like sisters, as Diawara said it, trading singing and dancing. Sangho told us of their meeting two years ago, when Diawara gushed to her about how she loved Sangho’s music as a youth and wanted to sing like her. Here onstage together, Diawara beamed as Sangho took off her shoes to dance and sang like a djelimuso. It was a beautiful close to a night that brimmed with life and light.

Word is that Diawara has been in the recording studio recently and that we can look forward to a record that pulses with the same vibrant energy that characterizes her live performances. For our friends in Europe, Canada, the Midwest and the West Coast, Fatoumata is coming your way, keep an eye out! Check out her tour schedule here.

Photos by Sebastian Bouknight