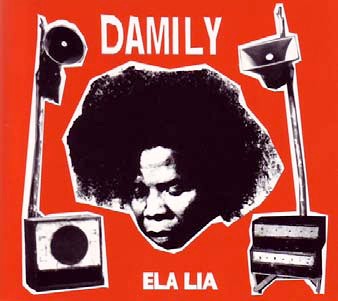

Damily is a veteran guitarist, composer, and bandleader of tsapiky [tsa-PEEK] music. In 2001, he fell in love with and married a woman from France, and the moved there soon afterwards. Damily’s band, organized by his brother Rakapo, has remained in Tulear. In recent years, he has brought them to Europe for tours, and they have recorded two superb albums, Ravinahitsy (Helico, 2007) and Ela Lia (Helico, 2010). Afropop Worldwide met Damily and his band at WOMEX in 2010, and we became huge fans of his music. This, in part, inspired us to visit Tulear, which we did in May 2014. As luck would have it, we arrived on the eve of Damily’s first public concert there in 14 years. A few days before the event, Banning Eyre sat down with Damily at his family home in Tulear. Here’s their conversation.

Damily, welcome back to Afropop.

Thank you, Banning.

So, I understand it's been eight years since you were last in Tulear, and 14 since you performed here. This is historic, isn't it?

Exactly. It's really historic. Because even the public themselves, they’re really happy. They're happy to see my name on a poster. We really wanted to make this concert for the people of Tulear. It's important for our history. Because our history started here.

Let's talk about the beginning of your career. Julien Mallet, the ethnomusicologist, told me that you started playing guitar when you were very young.

In fact, it was thanks to my mother. She and my brother, Rakapo, the bassist, we grew up together. And our mother was often absent because she used to go fishing to catch fish for us. So then, she thought of making a small mandolin for us, three strings, to help us pass the time. So, little by little, it evolved like that. Then the tsapiky arrived in a big way. And we tried to add our style into it, and that's how the group Damily got started.

A mandolin. Julien told me that these groups we've seen who play with three mandolins, and the bass, they basically are playing tsapiky.

In fact, ever since tsapiky has existed, all the traditional instruments, they play tsapiky now. It's not like before, when they played traditional music. No. When tsapiky started, the traditional musicians began to disappear, little by little. And now even the traditional instruments, they play tsapiky. They play it on mandolins.

It is very interesting that tsapiky has actually changed the repertoire of traditional musicians. What was the music they played before tsapiky?

They played music in 3/4 [ternary] time. Because tsapiky is in 4/4 [binary] time. Before tsapiky, the mandolin players played music in ternary time. That's why we call it traditional, because most traditional music here is like that. Tsapiky is binary, because it's not really traditional music. The influence in fact is more from modern African music, with the influence of the region--that's the essence of tsapiky, this style of music. But it's not really African. And it's not really traditional. It's truly autonomous.

Julien calls it "a young music."

Exactly. It's a young music. It was made in the 1980s. So it's still young. But it's been growing little by little, thanks to the musicians.

Damily with ethnomusicologist Julien Mallet (Eyre 2014)[/caption]

Damily with ethnomusicologist Julien Mallet (Eyre 2014)[/caption]

You yourself have grown up with this music, right? Because you started playing right around 1980, right when the music was being created.

Yes. I grew up with tsapiky, and I've passed my time with it, without thinking about doing anything else, right up to this moment, right up to today. I am always a tsipikist, loyal to my style.

Loyal. That's cool.

It's a kind of combat, in fact, because the style exists in Tulear, but because the fads change quickly, you see that there are some now moving on to other things. But normally, in Tulear, it's tsapiky. This town has really earned its claim on tsapiky. It's the town's own style.

Julien calls tsapiky the flag of Tulear.

Voila. It's the identity of Tulear.

So let’s go back to the beginning of your career. Talk about what the work was like back then. Were you playing weddings?

In fact, me, right at this moment, I still play with the same group. This group has existed since the 1990s. Right up to this moment, you find the same group. We have replaced the traditional musicians. That's to say that we played for traditional ceremonies. It was amplified music, but people accepted this music to be played in their traditional ceremonies. The return of the dead [famadihana]. The circumcision. The burial. At all the cultural events, tsapiky was there, especially at the return of the dead and the burials. We have our own different way of having ceremonies here in Madagascar. And often it concerns the dead, because we Malagasy believe in our ancestors. It's the ancestors who bring our messages to the Creator. And for that, everyone holds these ceremonies to make the ancestors live again.

Damily and band at the Alliance Francaise, Tulear. (Eyre 2014)

Damily and band at the Alliance Francaise, Tulear. (Eyre 2014)

You were young, and not well known at the time. Julien has told me about the system for music at these ceremonies, and how managers or proprietors owned all the equipment, and controlled the lives of musicians to some degree. Is that what it was like for you?

Yes. That’s how it works here. We, the musicians, we don’t own our guitars. I got my first guitar in 2001. It’s crazy, isn’t it? But that’s how it was. Because we were poor. To buy a guitar, that’s expensive. That’s why we had to work for the ones who own the equipment. So is this guy who owns the material who pays the musician. He pays them three times nothing. But he says, "You see? The musicians are playing their music." But he is the one who benefits.

He came to my place to ask me to play using his materials in Tulear. Me, I was born in Tongobori, it's 160 kilometers from here, in the countryside. My brother and I were both born there. But it was thanks to music in fact that I came to Tulear. It was the producer who came to find me in Tongobori to ask me to play using his materials. I accepted his conditions. The condition was food and lodging. That's it. But it was already a lot for me. To live in the city with someone who puts me up. I got to work, to put my group together. There was Claude, Naivo, Gany Gany, Rakapo. I put that group together and it worked. We became really stars of this region, with our own tsapiky. And that worked. We made many tours of the whole region of Tulear, thanks to our compositions.

Let me get some dates. When was the first professional gig you played?

It was a ceremony, in 1985. We started in ‘85.

So first gig in 1985, first guitar in 2001. That's 16 years of playing…

… Without my guitar.

And when did you form your own group?

In 1990. From 1985, I played with a group from the countryside. It worked, but at certain point it broke up. We separated. Then I put together my own group with Claude, Naivo, Gany Gany, Rakapo. Everything worked with them. We were bonded together. That was the really important thing.

In the beginning, when you were playing with the group that the producer put together, was it hard? I know you have to play very long periods of time, maybe three days straight, during the ceremonies. Maybe more. And you’re not earning much. But how bad was it? How much would you be paid for a three-day ceremony?

For a ceremony? As I remember, it was three times nothing. Centimes. Two centimes.

Three times nothing, eh?

But I was happy. I was happy. Because for me, I didn't know you could play with equipment like that. I didn't know. And the proprietor, when he gave me those centimes, I was happy. I was proud. That made be want to work harder, because there was money in it.

But it was more about the experience than the money.

Yes. That was what interested me—the experience. Me, I was satisfied with the money. At the

end of the day, I was poor and, in my head, I never thought I could become rich. So I accepted the conditions that existed at that moment, as an employee of these people. The money was three times nothing. And not just for me. For the whole group. We were all paid three times nothing. But what interested us was the music, and the ability to play. Because we were playing all the time, all the time, all the time. The performances were there. That's why people in the band accepted it. It was just good to work.

Okay, so in the beginning, you were playing with groups that the promoter put together. But then you formed your own group. What year was that?

1990. We released our first album in 1994. Here in Madagascar. It was recorded in Antananarivo. The official release was in Antananarivo.

What was it called?

Zafodrano.

How many cassettes did you release before you left Madagascar?

Before I left Madagascar, I released six albums.

Julien gave me one of the old ones. It was called Lazan ny Tany.

Lazan ny Tany.

Can you tell what some of the songs were about?

OK. In fact, most of the words talk about daily life. But sometimes I write songs that are sort of rhymes. For example, I wrote a song that tells the story of Madagascar and Tulear. I said that Madagascar has six children, because it has six provinces. So I wrote that. Madagascar has six children. Five boys. But Tulear is a girl. So I want to tell you the story of Tulear. For me, Tulear is a beautiful girl, because she has beautiful skin, like tsapiky. Earrings of gold. A necklace of sapphires. And shoes like the earth. All that is found here in Tulear. That's why they say it's beautiful in Tulear. So that was one song, in case you hear that Tulear is a beautiful girl. [Laughs]

Great. Another song?

Ravinahitsy (Helico, 2007)

Another song that was a hit here was “Liamboro Nomal” [Literally “Yesterday’s Bird,” but something like “Bygones.” Damily rerecorded this for the album Ravinahitsy.] The song in fact was publicity for us as a group. If you want to find Damily, he lives here. If you want to find Claude, he lives there. You see? If you want to find Naivo… It was something like that. But here, we don't need to make songs like the French songs with words like that. Words depends what kind of music you are playing. Because we were making roots music, tsapiky roots, for mandiarapotso [funeral ceremonies], so our songs were roots too.

Daily life.

Daily life. That's it. We amuse ourselves. That's it.

We did an interview last week with D’Gary. He talked about his early days as a tsapiky musician. Do you remember him at that time?

No. In fact, I didn't know other musicians who played tsapiky. Because for me, tsapiky was the bal poussière [dust dance] and the mandriapotso. That was it.

You didn't meet a lot of other artists. Because you would be the only group playing at the ceremony, right? It wasn't a community of artists.

No, no, no. In fact, the problem was that we tsapiky musicians were seen as vagabonds. We were poor. We didn't dress properly. This wasn't interesting to other people. We were just common musicians in the city. Because most of the musicians didn’t live in the city. We came from the countryside. We didn't really know who the other musicians were. If you were from Tulear, you could get together with other musicians, because you were all in the city.

Teta and Damily--two stars of tsapiky (Eyre 2014)

Teta and Damily--two stars of tsapiky (Eyre 2014)

When we were here in 2001, we bought a lot of cassettes. And I noticed that most of the singers who were singing on those cassettes were women. Why is that?

Actually, it's thanks to me that there are women singing in tsapiky now. Before, that didn't exist at all, women who sang. I brought a girl who sang well and we brought her in the group. And she became known. Before, it was only guys like Claude who sang. But women, it's good to have them in tsapiky, because they have beautiful voices. There are different ways of singing in Madagascar. There's choral music. That's in the city, because that comes from the church and all that. But in tsapiky, today, it's not like in my time. In my time, there weren't that many musicians. Now it's different. It's everywhere. Now, tsapiky has different styles. There's “roots tsapiky,” and there’s “city tsapiky”—that is with keyboards and things like that, trying to give a Westernized image of tsapiky. The roots tsapiky, mandriapotso, that is under the trees. That's what my group, Damily, plays. Under the trees, where the ceremonies happen. For me, if you want to be a real tsapiky artist, you have to play mandriapotso, under the trees.

When did you move to France?

It was in 2001.

So that was when you got that first guitar.

Voila.

I have the two albums that you released in France. I really like them.

Oh. Do you dance to them from time to time?

Sure. In the house.

That's very good.

When will there be a third record?

In fact, since coming back to Madagascar, we have recorded the third album. We did it at Studio Balafomanga. The recording is done. It went really well. It was an important moment for all of us. We are very satisfied with the result. Now we are working on the mix, but most of our work is done.

Can you give me preview? Especially about the messages? The songs?

Yes. It's about this moment in Madagascar. Because here, for some time, the bandits, and cattle rustlers and all that have come—I talk about all these things, just to touch on them. It's not an aggressive message. It just tells the story. It's like a souvenir of this moment. Because once it comes out on record, it goes everywhere. It stays. So there are some soft words too.

Soft words on a hard subject.

Voila. There are no politics in it. I don't sing about politics.

What's the title of that song?

“Vera Homby.” That means "Lost without cattle."

So I have heard a lot about this problem with the cattle. What is the story?

Us too. When we arrived here, everyone was talking about this. Everyone saying the same thing. “It's dangerous.” Things like that. Everywhere. Even in France, I was reading about this in the newspapers. That's how I came to write the song. Because this assault was happening here in Madagascar. I wrote this song to mark this year, and what has been happening.

So now you been back here for the first time in eight years. What's different from when you were here before?

Tulear. Well, the tsapiky has changed. The style of guitar. Tsapiky is based in the guitar. That's why it's always the name of the guitarist that names the group. So when I left, Rakapo took over the group. He doesn't have the same way of playing. He wrote his own songs, and all the young people today follow that. And now, it's a kind of tsapiky that goes outside the three forms. Because in tsapiky there are three parts. First form, that's the part where you have the singing. We call that kitariky. The second part is the acceleration. That's what we call kilatsake. And the third part is to break up the ambience a little bit. That's called kifolake. But in the tsapiky of today, there are not these three parts. They just have the last one. Right to the end. People dance. But it's not the same dance that we had before.

Is it less animated?

Yes, it is less animated. It's repetitive. People move their shoulders, from beginning to end. That's it. But in our time, it was not like that. The beat made people move their whole bodies. Everywhere. The shoulders, the ass, the legs. Everywhere. But this music they have now, there is no more like that. If it not still the same tsapiky, it's because people have forgotten. The guitar has changed too.

So this is not a good change.

Promoting Damily's concert (Eyre 2014)

No. For me, something is missing. But it's normal. Because guitar is not easy, right? [Laughs] It's not easy. For me, I had to work a lot to get good. I worked a long time, a long time to find my place. Music is hard.

Well, you mastered it. But has it really changed that much? I still hear some nice tsapiky around town.

Music has changed here, not changed completely. It used to be you heard only tsapiky here. In the bars, everywhere. Everyone who played everywhere. Now, since the arrival of the telephone and the CD and all that, a lot of musicians have the tendency to imitate America. They want to play the same thing as American variety. That's too bad. I don't say anything; I don't want to tell them what they're doing is not good. I don't do that. So it's American variety music. Especially in Antananarivo. It's like New York.

Yes, I've noticed that there. But you say it's happening here too. But what else has changed?

For me, a lot of changes, because the population is not the same. It's younger. People who are two and three years old when I left are adults now. That's the big change. The Tulear hasn't really changed. It's still Tulear for me. There are some pretty nice houses going up. But it's still Tulear. I love it.

Let's talk about the concert on Saturday. What are your expectations? What's your message for people?

The message is clear, I think. Damily is tsapiky. Damily is Tulear. Group Damily is going to play in the Jardin de la Mer [Garden by the Sea] for Tulear. It's not new, in fact.

If you were not here all those years ago, it will seem new. But the public of Tulear, they know us well. We were together for 10 years. At least.

They haven't forgotten.

No. They haven't forgotten. I hope they all come, and dance with us, and enjoy the moment. It's important for them, and for us also. Because this is the history of tsapiky. They're the ones who cared for me. Who made me known for the style of music. So they must profit from our visit here truly are. I'm doing it for free. It's a gift.

Great. I'm so happy to have the chance to be here at this moment. We are almost finished. I'm interested in what you are saying about the three parts of the song. And how the guitar style has changed. I met the guitarist Pascal in Tana. I heard him play tsapiky in the nightclub, Le Glacier. And when he played tsapiky, it filled the dance floor. But it was really the only time I heard that music played there. I guess my question is, what you think is the future of tsapiky in Madagascar? Is it coming up? Or will it just stay where it is? Big in Tulear, but not that big elsewhere. What you think?

Well, we are not many who have tried to take tsapiky international. There is my group, group Damily. Apart from that, there aren't others. Why? Because there aren’t producers here. The aren't programmers who come here. There's not a lot of curiosity, in fact. Because you have to be curious when you come here in order to taste this experience. So tsapiky rests in its corner. It's not disappearing. It's here. It's evolving. Everyone has their band. Everywhere. So you have to say that tsapiky has evolved. But to go international, that's difficult. Who is going to program this music?

And also, here in Madagascar, we aren't that interested in our own culture, our proper culture. So I said, “I'll just leave it. I'll just go off on my own. I'll continue, because I'm a musician. This is my music. This is my style. I grew up with it. I can't just leave the tsapiky like that.” So I am trying to bring tsapiky into the international scene, to raise it up.

Crowd gathered for Damily concert (Eyre 2014)

Crowd gathered for Damily concert (Eyre 2014)

So what's it like in Europe trying to do that? What's the reception, in Paris, in France?

We started our international career in 2006. It continues always. We’re beginning to be known, in fact. Internationally, in the realm of world music. That lets me keep living. We haven't changed the music. We haven't mixed it with rock or jazz. Excuse me, I don't know those things. I didn't study that in school. This is the music I've composed. And that's why I can play it so well. Because it's my composition. I don't do interpretations.

That's fine. Because it's rare. And it’s special. Thank you.

Damily band live in Tulear (Eyre 2014)

Damily band live in Tulear (Eyre 2014)