David Aglow is a man after Afropop’s own heart. He’s a world traveler in search of living local folk music that has survived the forces of globalization, and that escapes the attention of global music vendors. His collection of marginalized, mostly guitar music from Botswana, I’m Not Here to Hunt Rabbits, is a sterling example. It’s a vinyl release, with bonus tracks online, and it comes with a 36-page book providing rich and often surprising context about the artists and their songs. Banning Eyre met with David in his Brooklyn apartment to discuss the project for the program "More African Guitars." Here’s their conversation.

Banning: Nice to meet you, David. Why don't you start by introducing yourself?

David: Well, my name is David Aglow. I have a small record label called The Vital Record, and I release music that I think is important, overlooked and undervalued.

How long have you had the label?

I guess I formed it in 2010, And it's still what I would call a hobby, kind of a passion project. I didn't release anything until 2011. I've only got four releases, this is my fifth release.

Always vinyl?

No. This is my first vinyl. Part of the issue is that CDs no longer sell.

That is a problem.

I released what I thought were some interesting CDs, one that got reviewed by the Wall Street Journal. But I haven't sold anything really.

What kind of music was the other releases?

I traveled a lot in the Amazon, so I was doing music from the Amazon.

That's a tough sell.

Right. Especially one called The Amazon Fiddle Lamentations of Don Francisco Pezo Alva (2013). It's a tradition down there in the jungle where they play violin for the recently dead, and they sit next to the corpse for 12 hours, and they try to make people cry. It's a disappearing tradition. It's very interesting. I think if I'd made a movie out of it, it might have sold. But as it is now, I've sold about 12.

And then, I've done some what they call “jungle cumbia” from that area, and I did a rerelease of a jungle cumbia album from 1970, which is the one that the Wall Street Journal wrote about. It's very cool, but the sound quality is poor. There's only very few vinyl copies that exist of this anymore, maybe 10. They didn't put out very many. It was for local sales. Anyway, it's an interesting album, but I think I sold 100. Of course you get a lot of streaming. Not a lot of downloads. And from streaming you get very little money. We did a giant booklet with an Amazon historian with the same designer who did this book. He's an amazing designer. His name is Christopher Knowles.

At any rate, as you watch the “business” shifts, you realize it's really going towards vinyl, and my idea--and this is my first real foray into this--is to try to create really beautiful objects that are useful to own. So as you flip through the booklet, you don't have to read it all at once. You can read just part of it. I try to make it entertaining, engaging, informative, so this music can mean more than it would if you didn't have any of the cultural context.

I am running into more and more projects with this kind of impulse to educate listeners about little-known music. In this time where music is so disposable, you can let it fly by without thinking about what it means. But at a certain point, you're hungry to know more.

I hope you are hungry. You should be hungry. We should be hungry. Because in my opinion we are culturally famished these days. So that's part of what I want to present. And the stuff I present generally isn't easy listening. I like stuff with rough edges, stuff that has a certain indifference to acceptance by our culture.

Yes, that changes the quality of music altogether when they really don't care what folks like us think.

I love that. For this one, I was lucky enough to get a great release partner for the project.

Piranha Records in Germany.

Yes. They are giving it more of a PR push than I have ever been able to do, and so we’re getting interviews with people like you. NPR wants to do something. But they want to get interviews with the artists. They said, "This isn't going to work without an interview with the artist." So first of all, only two of the artists even speak English. Second of all, you can't find them. You can't make an appointment with them.

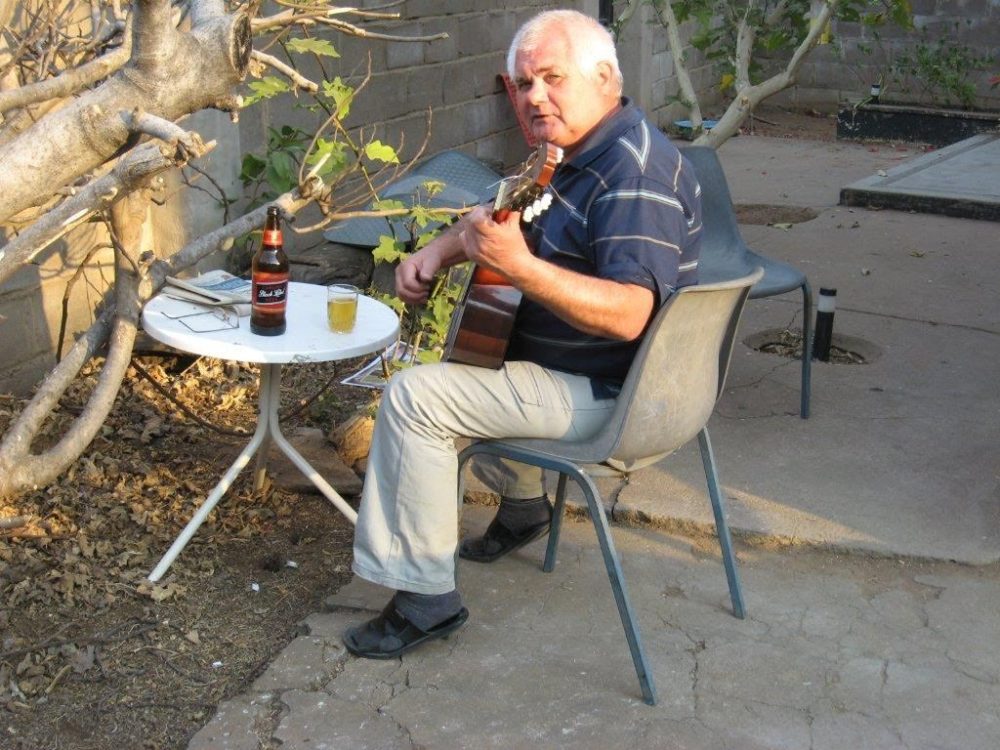

They are completely free spirited. They are true itinerant musicians, most of them. And they live day to day. And so for example, let’s talk about the wonderful man, John, or Johannes, Vollebregt, a good friend of mine now, who is the guy who posted these videos on YouTube. He is just a music lover. This guy loves music. And he's such a big-hearted guy. He's lived there for 30 years, and he was putting these things on YouTube. I can reach John, and John is going to do the interview with us. But for him to find these musicians, get them to come to his house and blah blah blah—very difficult. I said, "John, tell them this is the difference between them making music in a little corner where they make music, or getting some recognition, and the possibility, maybe, to tour or something."

And he comes back, "David, these people don't care. They care about what they're going to drink today. And that is it. They don't care. You could tell them anything." For example, do you know the jazz pop singer Joss Stone?

Yes. The English singer/songwriter.

So, I am working there with some filmmakers. My idea ever since I started was to film this stuff as well. Because in order to get the cultural context, especially if it's challenging music, or music that's not easy to understand, it helps to have a visual. So there's a filmmaker now who's going to go down there with his team. This is an African filmmaker who lives in England. He's from Zimbabwe. Anyway, he found out about Joss and he emailed me, “What do you know about this Joss Stone video?” I said, “What are you talking about?” He said, “Ronnie is playing with Joss Stone.”

So I googled it, and here she is with what looked like to me well-produced video. She's there with her backup singers and percussionist. Ronnie is in the background, playing whatever he plays. He has no idea who she is. And so I called John up: "What about that Joss Stone video?” He said, “Ronnie told me about some white woman who owes him money.” I mean, she surely paid him, but for him, she was just some lekgoa, as they say, some white foreigner who came to get music. He didn't care. It could've been Beyonce for all he cared. I love that. That's the kind of stuff I look for.

These artists don't care. This interview thing, that's our fetish. We want to understand. Get the story. Figure it out. And Ronnie, who is the face of YouTube, is a man of very few words. He doesn't speak much. Ever. He is an amazing presence, almost like a spirit being. He's got the smile, and there's a magnetism about him, but he is the gentlest soul, a truly peculiar being.

Ronnie the one who plays in the shebeens, but only during the daytime.

Right. Because he's such a gentle soul, they rob him. Especially at night. And he is the one where I showed up, and I'm like, "Where's your guitar?" Because I’ve got my field recorder, I'm ready to do some stuff, and he's like, "I don't have it." And I'm like, “Well, I'm here to record. Where's your guitar?” And through an interpreter he says, "I lost it last night.” "Where?" "I don't know. In a bar somewhere."

And I'm like, "Well, this is a big problem.” And he says, "They always bring it back to me." Because they want him to play it. There are people who walk around looking for him to give him his guitar back.

I have also seen these videos. People always send me guitar videos. But I remember one where one of this guitarist was playing with a spoon.

That's actually South Africa. I believe he has passed now. John has recorded him. John met him when they went to South Africa, because those guys did do a little tour to South Africa once, I believe it was in 2012, and they played with that guy.

O.K. Let's go back to the beginning. It was the YouTube videos that first got you. Tell me the story of how a video led to this release.

Well, I got an email that said, "The only way to play guitar." And I thought, this looks like spam, but it was from a friend of mine, so I clicked it, and I saw the video of Ronnie. His most famous video. It's called "Happy New Year." And he is playing in this Botswana style that is so different from anything I had ever seen before. And I thought to myself, "Wow, I wonder what this tradition is about. I wonder what's going on." I thought someone should really go down there and record that. Oh, someone must have.

And then I thought, "Wait a minute. I have a record label. I could go down there and record.” And so I got in touch with the person who posted the video who turned out to be Johannes Volbregt. He got right back to me and we started a conversation. He sent me to his YouTube channel, because this video was a pirated video. In other words, someone had taken John’s video and put it up on his own video site, and was getting monetized for it. John has never figured out how to monetize those videos. I don't know how much money he would've made, but it would've been a good amount. [“Happy New Year” has 1.1 million views.] He'd like to make some money for himself, but he’d also like to give some money to these artists. And often does. He's a generous guy.

At any rate. I started a conversation with John over the phone. This is before WhatsApp. Now we talk on WhatsApp, and it's free. I guess it took about two years to get the money together to do a little expedition. I went down there. I didn't really know what to expect. I had traveled pretty extensively in Africa, but never in southern Africa. When I met John, he was just my kind of person. An amazing guy. Very down to earth. Super funny. Very realistic. He's been there a long time. He knows the ins and outs whole thing. He's not idealistic about anything. He speaks great Setswana. He's a real character.

I find that any foreigner who lasts that long in Africa and doesn't become jaded, there's a kind of philosophical demeanor that develops. And a good sense of humor as well.

Well, he's a little tiny bit jaded. But still, he's one of those guys who is just so naturally generous. It's funny. We would go to a restaurant, and he would get frustrated because they wouldn't come over to serve us. It's a restaurant with nobody in it. Just waiters, fanning around. He would get up and he would tell them in Setswana, “We are your customers. You must come now and ask us what we want to eat. This is a restaurant." Stuff like that. But he does it in a joking way. He’s just hilarious, But in the end just a warm, bighearted guy.

And he plays guitar also.

He plays. I play. But just for fun.

You say you have traveled a lot in Africa. Was that for music also?

Unfortunately, no. It was when I was younger. I don't know why, but I was just drawn to being there. I wish I had traveled with a recorder back then. I was in my 20s. I went across Africa at the equator.

Congo.

Well, back then it was Zaire. I went from Kenya to Cameroon. Zaire was a hairy, hairy place. Back then it was "one of the most dangerous places in the world." This was in the mid-'90s. When Mobutu was at the very end, and there was lawlessness, which it turns out isn't quite as dangerous as a lot of places now with the fanaticism and all that stuff.

There was no currency really to speak of. There were no services. No transport. Nothing. No mail, no banks. I taped the money to different parts of my body and I had a lot of luck. And of course, the army then wasn't paid by Mobutu. They were just given permission to loot. So when you ran across those guys, it was…

You had to pay out?

Well, or talk a long time. Bore them.

Did you try to make friends with them?

Lots of time they were so wasted. Or you make friends with one of them who is not quite as crazy, and you travel with him and you pay him. So various things. I went up the Congo River and overland up to the Central African Republic. And you see things. I remember seeing a blind musician playing something that looked like a smaller kora. This is in Central African Republic. It was a single-plane instrument.

It was probably related to one of those East African lyres, like the nyatiti in Kenya.

Probably. Anyway, a blind man playing this, and a little girl leading him around, and she would bring him to people and he would play and sing. He was singing to me in French that he needed soap to wash his hands and this kind of stuff. It was just so beautiful. Those kinds of things are the kinds of things that I want to record now if they still exist. To me, music is the last outpost of real culture.

Well, you found a great one here. I have a special interest in guitar music and particularly the ways that different African players will reinvent the instrument one way or another. I spent a lot of time in Zimbabwe and heard about musicians like this, itinerant players. But it was talked about as something that had disappeared and didn't really exist anymore. It probably did in some rural places that I never got to. But there were itinerant guitarists back in the '50s and '40s.

Sure. George Sibanda, one of my favorites.

Exactly. But it seemed like that was really over, and so to find that there's this pocket in Botswana where something like this still exists and hasn't really been noticed except through YouTube is fascinating to me. And of course your recordings are very satisfying. These artists are so talented. And in the playing you hear South African and Zimbabwe influences seeping in. For instance on this collection, Sibongile Kgaila is playing electric, and he says he admires Leonard Dembo, the late Zimbabwean sungura star. Let's just talk about him for a moment. He's playing without drums.

That's right. No drums. No other musician at all.

So what do you make of an electric guitar style that so rhythmic, and I figure people would probably dance to, but with no drums. Is there just not a lot of drumming around here? Or is there something else going on?

What Sibongile said when I asked him about six-string guitar was, "Now, you are moving into jazz." But jazz for them… what they really mean is popular song. For example, I went to see concerts up there with their usual band set up the bass and drums and all that kind of stuff, and what sounded to me like South Africa guitar pop, highlife—complex, lyrical African music.

So there are still bands there that do that.

Yes. There are bands that do that, but he made the distinction, "This is traditional. This is folk. This is good for our purposes." So they are really one-man bands. And Sibongile isn't quite the itinerant musician that say, Ronnie and Western [Machikilani] are. But he does play bars, rural roadhouses and stuff like that. And he plays for tips. Their are lyrics to songs I recorded that didn't end up in the collection where he's talking about getting money out of your pocket. He's giving you a forecast. “And now you’re going to reach for five pula and put it in my box.” Five pula is about 50 cents.

I would ask questions about it, but again, they don't really answer questions like that. They don't understand what you're asking for, or why it's even a question for you. There’s an anthropologist who said, "Asking questions is no way to get answers." Which is kind of my mantra. So I try to chat and get them talking. It's almost as if you go to see finger-style blues and say, "Where's the band?" I am the band. This is finger-style blues

But there are bands. And in Sibongile, I really hear that Zimbabwean guitar band influence. Sungura. But are these bands operating in the same sphere? Is it a question of rural versus urban?

I wouldn't call it rural so much as marginal. It's occupying a very marginal space in Botswana culture. For example, the sungura bands you are talking about, they will play concerts and restaurants. They've got their modern electric guitar, amplifiers. They are professional musicians and they get paid to play. People dance. That's one kind of music. And we have some artists, some singers and stuff like that who are big in Botswana. So this would fall in the category of traditional music, which is not seen as sophisticated. It's seen as a little backwards. Nowadays, the young people are more into hip-hop and you can’t imagine how many questions I fielded about hip-hop from taxi drivers who are reading Source magazine and Vibe magazine, and they're asking me about 50 Cent and I'm like…

You are asking the wrong guy.

Right. But the other issue is they are in a real tricky space because of a government that wants to support traditional stuff, traditional Setswanan arts. But these guys are drinkers. They are bohemians. They are itinerants. They don't put the folklore, from the government's perspective, in a good light. So they are occupying a little marginal space. For example, when I had gone to the embassy in Washington D.C. looking for support for this album—some money, something. I met the ambassador, who is a wonderful man. I don't know if he's still the ambassador. His name was David Newman. A British guy. So I showed him a little video I had, I talked to him about it. I never got anywhere. They don't really want to get behind this music because it’s music from the bars, and it’s music about things that don't necessarily show Botswana in a good light.

Was there a religious element to that?

Not that I saw. No. There is a lot of religious music, a lot of the choral singing. Some of it sounded quite nice to me. But no. I didn't see a lot of religious stuff. Certainly these guys never talked about religion. They tended more towards what I would call traditional religion.

I'm curious because I’m hearing more these days about churches, particularly Pentecostal evangelical churches coming in and offering a powerful message of prosperity through faith and prayer. These churches often frown on things that I hold dear—like traditional religion and the music that accompanies it. This is clearly on the rise in many parts of Africa, including Zimbabwe.

And the Amazon.

Yes. I encountered it recently in Brazil—disrupting candomble ceremonies and such.

Don't get me started.

I wonder though, from the government's point of view, is that a factor? Or is this something that precedes those churches?

I never go as an academic or journalist. I go as a music lover and someone who is passionate about small traditions that are in danger of being overlooked, forgotten, undervalued and extinct. But from what I could tell, and I spent two months there, the government really frowns upon drinking, for whatever reason. It's not illegal.

For good reasons. Religion aside, there's a lot of alcoholism in that part of Africa.

Exactly. So the government really discourages drinking, and you don't see for example these kind of bar cultures that you find in, say, Congo or Kenya, where you can go out and have a crazy night.

And it seems like everything is funded by beer companies.

Right. Right. Or also in Bangui back in the day. There was one neighborhood I went to. Everyone told me not to go, but that's where the music was. And there was some Italian ex-pat there who said, "Ah, no problem. Great music here." I don't even know how I got back to my little hovel. You don't have that in Botswana. You don't even have the bustling marketplaces. Botswana is much more reserved. Decorum and politeness are a big part of the culture. You have to greet everybody, and call them sir and ma'am. To me it was refreshing. But it was much quieter. Even at the bus ranks. I remember fighting to get into whatever bus. But here, a quieter place. The drinking is much more subdued. And it's really only people who are hard core who go out to drink, and that's who these musicians are, and who they play for.

For example, Batlaadira [Radipitse Ke Nnete] and Solly [Sebotso Chaba Bakweni], they don't play in those environments. And they are invited by the government to play in their places. But they probably pick songs that are more…

Polite?

Yes, but that deal less with the subculture, the marginal culture.

Botswana hasn't produced any major popular artists as far as I know, certainly not internationally. I am always interested in countries that are right next to each other but have such different music cultures. Look at Zimbabwe, which has produced star after star. I was in Namibia a few years ago and I met Elemotho Galelekwe, one artist with a national reputation, and maybe there are a few others. But it’s nothing like the scene you have in Zimbabwe.

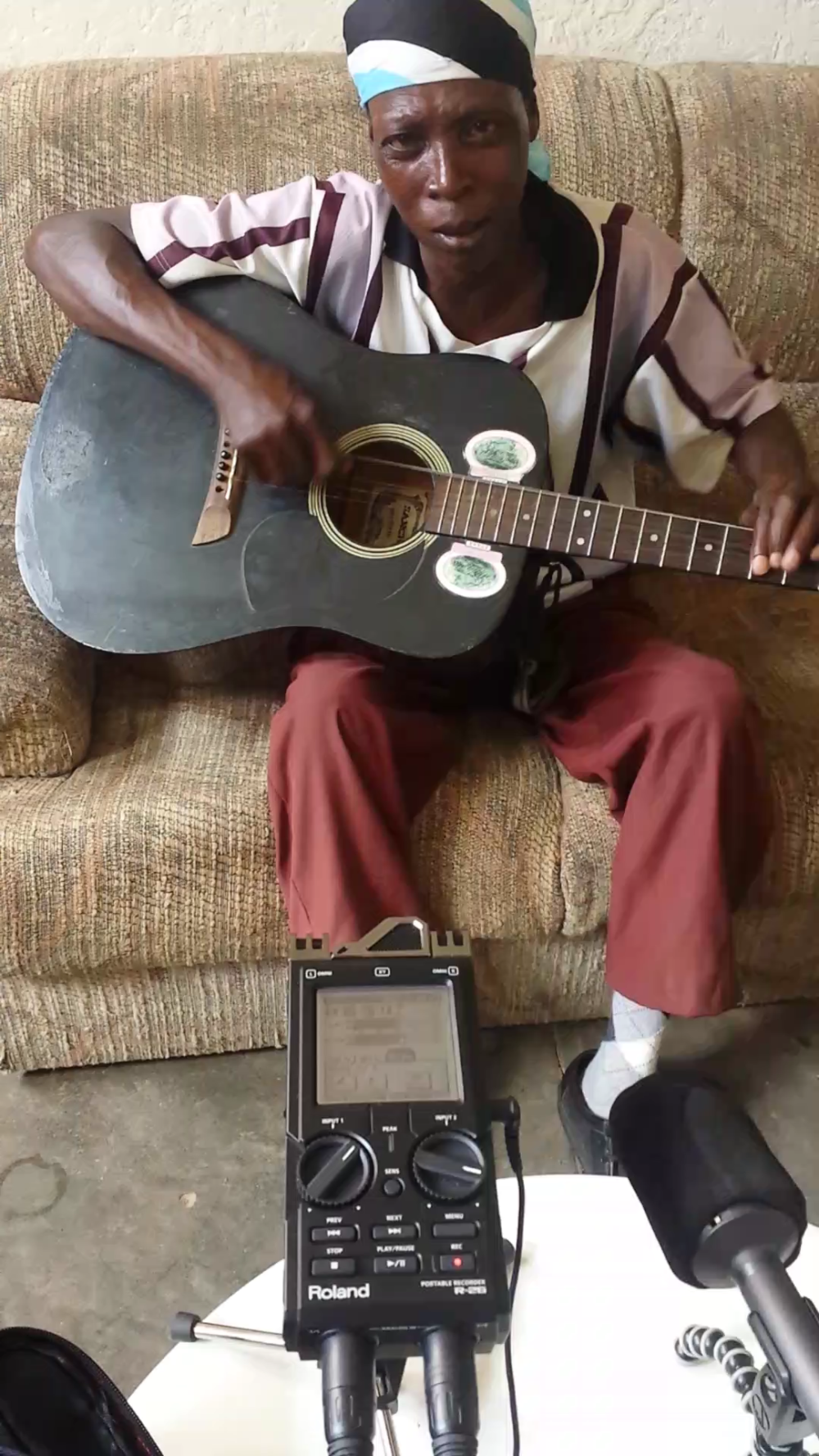

O.K., let's talk about the guitar style itself. For our listeners, describe what is unusual about the way these guys play.

What is unusual about how they play is that the guitar is strung with four strings. One is a bass string, a literal bass string from a bass guitar. If not a bass string, then a brake cable or something that has a lower sound. And then three treble strings, usually at the bottom. So bass string at the top, space in between, three treble strings. And then to handle the guitar, they approach it from over the top of the neck with their hand. They do not come underneath; their thumb does not support their fingers on the frets. Their hand just goes over the top of the guitar, and they use their thumb actively for bass runs and different things. The tuning, as far as I can tell, is what we would call an open tuning, open G on the guitars I handled. But again, without using A 440. They just tune it to itself, and they find something that works with their voice. In fact, there are recordings I've made of the same song where they’re in a totally different key, because the guitar was tuned differently that day.

Then the right-hand technique varies. They usually use some kind of a plectrum, but usually as a ring on their index finger, and then the use their thumb to hammer out the bass, but they can switch, and sometimes they’ll use that pick on their index finger to play the bass string. So when you watch it, you just don't know what's going on. And they know that you don't know what's going on, and that’s part of how they get their money. Because it's a show. And for flair, and that's one of the things that made that YouTube video so popular, is that Ronnie will do little instrumental runs on the bass string. He will pop it and pluck it in different ways, hit it with his elbow, make it speak, flick it with the back of his wrist.

I saw one guy in the back of a shebeen—which we were lucky to get out of alive—playing with his foot. I have no idea how he was holding the guitar. He gets his foot over the neck, and that's part of the visual appeal, the theatrical appeal that gets people to give him money.

Now the fact that it's in an open tuning means that they can play those chordal riffs with just barring, right?

Honestly, they weren't barring as much as I would have been barring. They have all these fingerings. Because the guitar is almost flat like that blind blues player from the '80s who used to play the guitar in his lap. Here it’s not quite on their lap, but they tilt it up to get access. He can look like he's playing the piano. The fingerings are like that. They don’t bar as much as you would think, and in fact, a bar is much easier to do from underneath, because you can squeeze it. So I don't know what they do. I swear. I was watching. I play guitar. Maybe you would've figured out something and played some stuff. I was just like, "Forget it." I did pick up the guitar around the guys, and I could play some riffs moderately using the three strings that were in open tuning. But it's harder than it sounds.

Now you’ve got me curious. I need to go back and watch those videos more closely. It’s certainly a refined sound.

Right. And in my opinion, the owner of the sound… I shouldn't play favorites, but my favorite musician is Solly. He is the one where you watch and you really have no idea what's going on, rhythmically very complex. And is also someone who makes real arrangements with the songs.

Tell us about Solly.

I don't know how old he is, probably in his late 30s or early 40s. It's a question I don't even bother asking. And he has had some success. He used to be the champ of that style of guitar before the young guys came along. He would win contests. He's traveled to China. I think he has traveled to some Scandinavian countries. He is a sharp dresser, and he has a very distinctive rough voice, the kind of voice I love. He's all business, a man of few words. He didn't want to chitchat. He's just like, "I'm here. I will do these songs for you. I won’t do those." I asked him to do some of his that I knew that he wouldn't do. I don't know why.

So is there a shared repertoire of songs?

No doubt. This is true folk music, which drove the people at Piranha crazy, because they had to copyright this stuff. We copyrighted recordings for the artists. They are the authors of these songs. That was very important to me. But I don't know if they're really the authors of these songs. That's the problem.

There's the business side. And then there's the reality side.

And that's true of real music everywhere. Certainly with the blues. How many times do you hear them recycling all those great blues ideas—Blind Blake, Blind Willie McTell. All these guys. They do versions of these songs, and who knows where they got them?

Solly is the one with the song “Chinese Goods.”

That, to me, is genius. That’s the stuff I'm looking for. You would never think of doing a song about that. I'd heard it and liked the song, because it has an unusual chord structure. Solly is quite inventive. It wasn't just a I-IV-V kind of thing. I knew the chorus. And then my interpreter who is this wonderful woman, very Christian, but super cool with everybody—I asked here what it meant. And she said, "You know what that song is called?" And I said no. And she said, “It’s called ‘F#@% You, Mother-in-Law.”

And I said, "What!?" Coming from her, this diminutive, incredibly proper person, this beautiful soul. ..She would never say a cross word to anybody, and I hear that coming from her. So then she explained it and it's about this style of skirt that came out in Europe that had a slit up the side and showed a lot of thigh. And for whatever reason, the people there really liked it. The younger women liked it. But it was expensive, so then the Chinese merchants got involved and knocked it off. They made the skirt really cheap. And so it became all the rage, but these mothers-in-law were getting offended. They didn't like the skirt. It showed too much thigh, and they were angry at their daughters-in-law because of the way they dressed. So he wrote a song about it.

But the funniest part to me… And again, don't count on these guys to be politically correct. They just tell it the way they see it. In his refrain that comes up a lot is a reference to these Chinese goods: "It was working when I bought it." So the refrain is, "Chinese stuff, it was working when I bought it." And of course, everyone hears that and they just crack up.

But imagine not knowing the story behind that song. It loses a lot. Now it becomes something so inventive, so beautifully mundane. It's about a silly fashion, but it reveals a whole swath of culture and how it's changing, and the opprobrium of the older generation to the way the younger generation dresses, and the Chinese immigration into Africa. It's touching all these subjects. That's folk music. That's the real deal. And of course, you can't ask a question about that. He's doing it as a natural function of his job as a musician.

So it wasn't from Solly that you got this translation.

Not at all. No. Wouldn't get a word out of him. It was all working with various translators.

I'm puzzling in my mind the comparison between this tradition and what I’ve experienced in Mali with griot songs, or in Zimbabwe with mbira players. There's a similarity in that the music is definitely associated with stuff that is marginal in terms of officialdom and modern religion and all that. But these are very old traditions, going back probably hundreds if not thousands of years. But there is also this idea of a repertoire in each case, maybe 10 or 15 songs that everybody plays, and everybody plays in their own way. This looks to me like a much younger version of the same dynamic, so then you wonder, you hear the three-chord stuff and you think about South African music and how was influenced by American music with all the I-IV-V progressions. And then the influence of Congolese music. Some of these ideas become part of the tradition even though it doesn't seem like they originated from Africa. Then again, who knows?

Who knows? Especially when you're talking about the United States. You can't separate our popular music from African music. They are together. Or take African rumba music. They took Cuban music? No, the Cubans took African music, and now the Africans took it back. Flamenco has a term for that called cantas de ida y vuelta, return-trip songs. So there are flamenco song styles that went to the Americas and came back and became flamenco-ized as something different.

Those stories are fascinating. We used to call that ping-pong.

So who knows. And honestly, I've thought about the I-IV-V stuff in general. Whatever set of chords you might have, it creates a foundation over which you can improvise. You can join in if you know the chords. You know the universe that's available to jam with. So in flamenco, it's not I-IV-V, but they have set patterns. So if someone is playing a solea, you can just jump right in. You might not know the song from anything, but you know what he's doing. Of course, there are subspecialties and it becomes very complex. But at base, it's kind of a democratic art form, participatory, inviting.

I remember in Mali, everyone plays something like blues. The feel of it, the character of the singing the blues scale. But if you try to get them to follow a 12-bar blues progression, trouble. People get lost.

In fact, they might get bored with it.

True. They have more freedom in that one chord tonality. It isn't even really a chord. It's just a mode.

I think that's the difference: structure, this industrialized, capitalist approach to the world. Part of my thinking on this is that that's what the 12-bar thing is. That's what that pounding beat is. Industrial.

Of course, it wasn't always 12 bars.

Right. And Lightnin Hopkins never played a 12-bar form. He plays whatever he wants to play. I mean, you could hear the musicians getting lost behind him.

And then you get the reverse phenomenon of guitarists in Zimbabwe interpreting mbira songs as chord progressions. It makes something mysterious understandable in Western music terms, even though the mbira musicians would never think of it that way. So then I wonder is there anything that you hear in this Botswana guitar music that feels precolonial?

Well, first of all, Botswana was never a colony. It was a protectorate. There was nothing there. Nobody wanted Botswana. They went to Great Britain to ask them to be a colony. And they said, “We’ll make you a protectorate.” Then they got independence, and Britain, said, “Yeah, sure, be independent.” And then they discovered diamonds! And now, it has to be one of the wealthiest countries in the world, I mean, for the size it is. You would not believe the university they have there. And the roads. Incredible.

But on the music, my sense is that the part that would be precolonial era is the ingenuity that goes into the style, and the tradition of the itinerant musician. The fact that they are talking about contemporary issues, the same way a griot might. I think that the music itself is in a way less interesting than all the things behind it, the things that are making it exist. The impulse to just grab a guitar, learn a way of playing that's completely unique to that area, in a way changing the instrument, and then adapting it to their style of life and the place. It's really adapted to the place. All the messages in these songs are strictly and solely for other Botswanans. With a few exceptions, they are not singing about anything you would know about if you weren't from there.

So I guess it's hard to get any real sense of the origins of this music. What about John? He's been there a while. Does he have any ideas about that?

No one has gotten very far with that. I don't know where you'd go to find that out. I asked around. I asked a lot of people. I asked all the musicians. Everybody said he learned it from somebody playing, an older person that they saw playing that way.

And they probably didn't get taught. They had to watch and figure it out, right?

Right. In fact, a lot of them say they didn't get taught. They wanted to learn, but whoever it was didn't want to teach them. Then they had to go and get the guitar and learn themselves. So I do think you need a guitar first. It doesn't come from an instrument that predates the guitar. And Botswana doesn't have the same kinds of traditions that South Africa and Zimbabwe have. I really didn't see any traditional instruments, other than the ones I recorded.

You recorded two. Tell me about those.

Well the first one, I'm not sure it's really traditional. It might just be an invented instrument. That’s the fenjoro that Babsi [Barolong] plays. From what I understand, it is a traditional instrument, or a version of it that's been disappearing. It’s a bowed three-string guitar, or violin. I guess it's a violin. To me, it looks like a mandolin, but just three strings, and bowed. Babsi is an older man. He's probably in his 80s. One of these salt-of-the-earth people, just a gracious man. He lives quite far from Gaborone, and the guy is an incredibly ingenious folk craftsman. You walk around his compound and in there are all kinds of chairs that are sculptures or traffic barrels that he's made into furniture. And his wife is there. She is collecting grass to make baskets. She's mending pots, and he might be playing music for her. In their yard, there are I don't know how many kids, all different ages, just playing. These are kids that are quasi-adopted by Babsi. As you know, AIDS was a chronic problem in Botswana. The rate has gone down, but it's still probably somewhere around 20 percent. Don't quote me on that. But it was more.

I know that Zimbabwe, South Africa and Congo also had serious problems with AIDS. But why was it even more serious in Botswana?

I don't know. Maybe because the population is so small that it was easier to get around. I'm not qualified to answer that, but for example, Lesotho and Swaziland also had high rates. Thank goodness, the rates have been going down. But Babsi has a very funny song: “You gotta wear a condom. You gotta wear condom." And so a lot of those kids in that yard, their parents would have died from HIV. Babsi is the kind of person who takes them all in. I don't know that he makes any money whatsoever, but he provides from the best he can. He's a security guard.

Anyway, he's a true creative. He's always doing something with his hands. He made his own instrument there that he says he saw someone playing it, and he wanted to make it. And he taught himself to play it at the cattle post, which is where a lot of these guys learn their craft. They are tending cattle in the remote areas, and you've got nothing to entertain yourself but what you can provide with your own instrument.

Did you ask him if there are other people who play this instrument?

I did ask him. He said the people who played before. He didn't know where it was from. He thought it might be from South Africa, and that he saw someone playing it in 1970.

Maybe it has some connection to the Zulu violin.

That may be more true of the segaba, the one-string instrument.

O.K., we’ll come to that in a second, but I want to ask you about this condom song. Because as you know, there are a million songs in Africa warning people about AIDS and urging them to use condoms. They're usually rather stern moralistic numbers. There's a lot of finger wagging. So I like it that someone who is so directly touched by this takes this light and humorous approach.

Well, it may be because he is so touched by the situation. He knows that a finger wag is not really going to accomplish much. He's kind of like a grandfather in that way. Like my grandfather never wagged his finger. He had a playful way to give advice and then it was up to me whether I would take it or not. Because he knew that if he just gave it to me, I wouldn't take it. So I imagine it's like that. It's a very funny song. He does use the word condom a lot. It's almost a strategy. He keeps repeating, "Wear the condom, wear the condom,” and then in the middle, he adds this joke, "That's for you young people. Some of us are old and worn out."

He's a delightful guy. He's John's favorite. John loves this guy. He says, "Babsi is music.” He's just always playing. He's one of these very beautiful souls, a real elder. And to be in his presence is very humbling.

Let's talk about this other traditional instrument, the segaba.

That’s Oteng [Piet], O.T. O.T. is a real charming guy, a guy who's been around, a tough guy. He speaks Fangalo, the African mining language. He was in the South African mining camps. He has a passion for traditional culture. He makes with his own hands the traditional outfits out of buckskin and all that kind of stuff. And he made this instrument which they associate with the San people, the bushmen. But from what I read, they think it's more of a Zulu origin. But it's got to be an old instrument, a very old instrument, a bowed, one-string instrument.

Yes. It reminds me of some of the old Zulu fiddle maskanda music, that strong, creaky sound. Even when they play on a modern violin, they get this cool, raspy sound. So it made sense to me when I read there was a Zulu connection there.

It's not fretted. The bow is scraping. I love those kinds of sounds, but there are people who don't. So that's their problem. Anyway, we went out to his cattle post, it was his uncle's cattle post, and he's always got his segaba and he's playing it out there in the bush, composing songs. He speaks English, so we were able to speak to him in English.

We should talk also about the one woman here.

Anafiki “Anna” Ditau. I don't know what to make of that story. [Anna tells David a story about having been blinded by her mother as a baby. The story has a number of shockingly morbid details, but she tells it with this sunny, cheerful voice, starting with "I would like to tell you a story…" You’ll have to get the album for the details!]

And that's word for word, because she told that part in English. We started rolling, and, "I would like to tell you a story…" I was never going to ask her how she went blind. She wanted to tell us. Now, between you and me, who knows? You know the old saying "don't let the truth get in the way of a good story?" But I can't imagine making that up. It's so horrific.

Of course if you dig into southern African folklore, there's some pretty raw stuff, and lots of people who are crazy and do crazy things.

Blind Willie Johnson was blinded by his mother who threw lye in his face when he was 8 years old. "Motherless children have a hard time." So blues is replete with those kinds of stories too. Whatever. I'm just there to record. If she wants to say it, that's fine with me. I mean, part of me hopes it's not true.

Anyway, Anna plays out in front of Choppie’s Supermarket. I don't know how many days a week, but that's how she makes her living. And she doesn't live in the capital. She comes in with her husband. They take the bus. Her husband accompanies her every day. And she's right there in front of the supermarket, banging out her hits. People know her songs. Everybody in Botswana can sing you some bars of "I Will Never Forget You.” Everybody. I don't how it got out there. She's played it on TV, yet she is still busking for money.

She has had some benefactors. She's got a nice little house. She is taking care of herself. She's got two kids and grandkids and all that kind of stuff. She is not an itinerant musician in that respect. She has a home.

She's probably an artist more acceptable to the government as well as a representative of folk music.

Hundred percent. Absolutely. But I don't know what you'd call what she does.

Traditional music with a Casio?

Right. There are some songs I didn't put on here where she sings about, for example, Princess Diana. Crazy stuff. And then some woman who taught her a few words of Swahili. She's got a song about that. Different things. She is not talking about the same topics as the other guys. She probably enjoys a glass of beer now and then, but she's not in the shebeens drinking the shake-shake, Chibuku.

Right. When I lived in Zimbabwe, it was the '90s, and they sold Chibuku in these brown jugs they refer to as "skuds,” a reference to the SCUD missiles used in the Gulf War. Their slogan was "Down the Scud."

Wow. Good luck getting it down. I tried it a couple times. I stick with the beer. But for a lot of these artists, people like Ronnie and Western, it's also a meal. Because you got all that starchy lumps in there.

The drink you're talking about is made with sorghum. The Zimbabwean one was made with millet.

Slightly different. This stuff is literally shaken all up, and it's lumpy and starchy.

But they still call it Chibuku. I wonder if that's the name of the company.

I looked into that. I think Chibuku is just a name for homebrew out of these different grains. And then they have the brand names. But I could be completely wrong. Maybe Chibuku is the brand name.

Maybe both. In Zimbabwe Chibuku the commercial version of seven-days beer, which had to be fresh for mbira ceremonies.

That was made with millet. How is that?

An acquired taste. Milky, yeasty, little bit sour. I got used to it. I was able to drink it somewhat, not with abandon. Let me ask about one more song, “Murraynyana (The Little Murrays),” from Sibongile.

That’s a beautiful song, and then when you find out what it's about! It’s literally about an engineering company, Murray, who came to build a road from Gabarone out to Kanye. And along the way, the guys who are building the road party at night and get a lot of people pregnant, and leave a trail of illegitimate children behind them as they go towards Kanye. So he mentions all the towns where they leave all these illegitimate children. Now this guy is the uncle who's stuck having to care for these children. And this is a real thing that happened. And in my world, I just can't imagine a song about that, especially in that way—matter of fact, funny. To me, that's the most traditional thing about this music to me. The point of view has got nothing to do with the way we are accustomed to popular music. It's really coming from a different place.

The little Murrays. So those workers who were getting the people pregnant, where were they from?

Probably South Africa. I think they were South African. So you still see that. A lot of times the contracts will bring in South Africans to do big projects. So Sibongile also has this rock song, “Gladys.” And I'm like, "Where does this come from?" It's like a punk band trying to do highlife, but it's him doing a punk song, and it's so funny. It says, "Everyone says Gladys was ugly. They said Gladys had rickets. Well guess what? Gladys is marrying a rock star." And it goes on like that. It's hilarious. That's one thing about Sibongile’s songs. People love his songs. They all know the words. They all sing them. He is a very funny guy. And again, I don't know where he got the idea of a woman called Gladys who had rickets and married a rock star. I have no idea.

At the end of my time there, I tried to organize his concert. I was having trouble finding a venue. And SIbongile got us a venue outside of his little town, and it was up a dirt road, in the middle of nowhere, generator power, florescent light. For me, paradise. And with this terrible PA system, and the guitars barely tuned, and he's drunk. Just a crazy scene, but when you settle in there, that music just washes over you. Everybody is screaming, but it is magic. Pure magic.

Those kind of moments are special. That reminds me of some of the out-of-town venues I used to go to in Bamako back in the ‘90s. Incredible atmosphere.

Let me say a word about Batlaadira, the young gun. Very athletic style of playing. And his lyrics are interesting. They are all culturally related, and they are acceptable from the point of view of the government. They're talking about reviving Botswana culture, black magic, interesting topics. When we recorded him, he was 20 years old, and very confident. I wouldn’t say full of himself, but he has a special talent, and he knows it. He wants nothing to do with the bar scene and the shebeens, the itinerant scene. He is going for gold. And his style of play is miraculous. He's just so fast. He's an athlete. He's a good soccer player, and he plays guitar like an athlete, super clean, super fast, super agile.

When you say he is going for gold, what is gold for him?

Gold for him is winning these government contests, getting taken to Kenya by the government to play for the president of Kenya. Things like that. The thing is these guys are not well served by local recording people. In my opinion, they put together these albums that are either terribly produced, you know with cheap drum machines and stuff like that. One of the reasons I want this album to be so varied is because it can be a little monotonous with just one of these artists. If you are live in a shebeen, it's not monotonous. It's where you are. It's like a bird song. It's beautiful. But if you're listening as a listening experience, politely in your living room... And I want you to do that. I've tried to package it in a way so that's possible. But you know what I mean. Blues can be monotonous too. And if you're a blues fan, you don’t hear the monotony, because you’re listening for those micro variations.

Mbira music is the same.

Right. I'm sure. One more to talk about. Western [Machikilani]. Western, another itinerant musician, very funny, singing songs about the cell phone, singing songs about contemporary issues, about being a security guard. There's an awful lot of security guards in Botswana. John said to me, "You have to understand. Thirty percent of the population has a good job. Thirty percent of the population has no job. And the other third has a job protecting the people with good jobs from the people with no jobs." And so Western has a song about the security guard.

I like the cell phone song, because it's blaming the technology for a human problem. It's not infidelity that's the problem; it's that the cell phone makes it so easy to find out if your spouse is cheating on you.

And it's breaking up people's homes. Hilarious. I mean, to me, that is genius. Because who would think of that perspective? And Western, for my money, beautiful voice—very penetrating, very honest. And then Ronnie, Ronnie's not good at recording. He's the star of the videos, but he's not somebody who's going to show up and record something. He's somebody you could record all night and get 10 minutes that are just amazing. But otherwise, he's very laid back. He's like the spirit being, very gentle. He's just a hoot.

So I'm guessing that when the European tour comes together, you will not want to be the tour manager.

John had a joke about that. Because now, with the problems and Zimbabwe, there are a lot of Zimbabweans coming to Botswana to work. There they are illegally. And at the end of the month, if they want to go back to Zimbabwe, they get themselves caught. They get rounded up, and get taken back to Zimbabwe in a kind of armored vehicle bus. They get packed into these buses, police vehicles, and they get a free ride back to Zimbabwe. That's all it is. They get caught on purpose.

And there are treated O.K.? They don't have all their money taken away and things like that?

I have a feeling that they are treated just fine. As a crazy example, when we were there, some of the people got their equipment stolen. And we went to the police station to make a report. I'm sure you know what that's like. But when we were there, it was Zimbabwe roundup time. So they had a holding cell that had no lock on it. And they put a couch in front of it. The cell was so full that the couch was pushing out. And the Zimbabweans from inside are pulling the door closed. Because they want to get their free ride back.

And so when we talked about a tour with John, John said, "David, I think you're going to have to get one of these buses are using with the Zimbabweans to take them back." Because that's the thing. A tour? I'd love for all of them to get money from a tour, but...

So if someone give you $100,000 and said, “Go ahead and do a tour,” you don't think you'd be able to get all of them?

I think you could bring all of them. I don't know if you could get all of them to show up the same night. That would be a hilarious thing to follow with the camera. That would be amazing. So if anyone is out there who wants to fund that...

It would be a joy.

It would be a hoot.

Well, thanks so much. It’s a fantastic project and we thank you for doing it