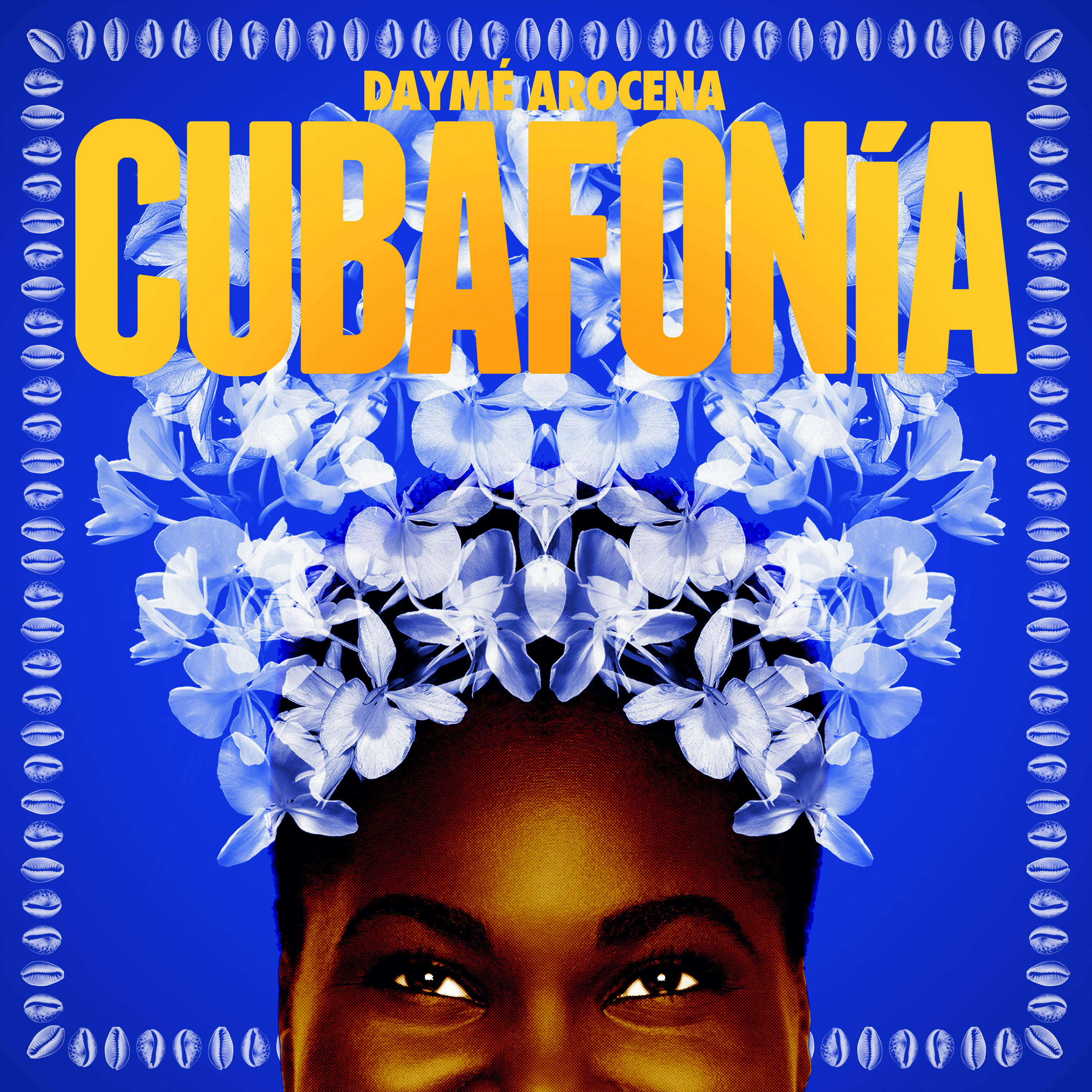

After two years of extensive and well-received international touring, Cuban rising star Daymé Arocena returns with her second album, Cubafonía. The record sees the 25-year old singer, composer, arranger, choir director and band leader as strong as ever, as she turns her focus towards the musical richness of her native island, exploring its vast rhythmic and melodic landscape through 11 ambitious compositions. Staff writer Alejandro Van Zandt-Escobar spoke to Daymé by phone from her home in Havana, Cuba to learn more about her new album, her recent conversion to Santería and the beginnings of her international career. Cubafonía is out on March 10, 2017 on Brownswood Records.

This interview was conducted in Spanish. The original transcription can be found here.

Alejandro Van Zandt-Escobar: Hi Daymé. Where you are now?

Daymé Arocena: Hi, I’m Daymé Arocena, and I’m speaking from Havana, Cuba.

So we know you have a new album out soon, after several other records with great success. How is Cubafonía a step in a new direction relative to what has come before?

What’s happening with Cubafonía is that it’s a record made up exclusively of my songs, written with the goal of in some way recreating the typical and traditional rhythms of Cuba. Because what happens is that people know mambo, people know chachachá, people know a lot of Cuban rhythms but don’t know that they’re Cuban. So with this record I’m trying to get the world to recognize Cuban music, and through my songs it forms an exploration of the rhythms and genres of Cuban music which are integral to the history of music on a global level and which, maybe because Cuba is a tiny island in the middle of the sea, people don’t always recognize as styles born in Cuba.

I’ve noticed your mastery of various musical styles at your concerts. Can you tell us about your musical background? How did you learn about and become proficient in all of these different Cuban styles?

Well, I’m an academic musician. I went to music school, I studied at the Amadeo Roldán Conservatory, where they teach us Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Strauss, Mahler and Wagner … but they also teach us the Cuban classics. And at some point we play the classic styles of popular Cuban music, though without giving them great recognition because the school is focused on classical music. But we understand them, we recognize them and we study them. I think that school was my first connection to traditional Cuban music styles. And after that, the street, and life in general, taught me how beautiful they are and how influential they are on the lives of every Cuban, musician or not. So that’s where it began, my complicity with the musical styles which I was born into. And then what happens? In the case of rumba … there are genres that we are more in contact with, because people play them in the street, hear them, feel them … but there are genres like changüí which are completely autochthonous and which are really from the end of the country, they can be found in Guantanamó and in far-away provinces. So it’s hard to follow those rhythms and I couldn’t encompass all of them in my record. I tried to put tango congo, old-school rumba, modern rumba, pilón, bolero, chachachá, mambo … but many styles are missing. I missed dengué, nangón, sucu-sucu … even the conga! You know, Cuba is a sage, it’s a mountain spring of music, I’d even dare say it’s a powerhouse. I’m willing to say that whoever really wants to be a musician needs to visit at least three countries in their life: Brazil, the United States and Cuba.

Have you traveled a lot throughout the island to collaborate with musicians, or have you mostly been based in Havana for your musical work?

That’s one of the things that I owe myself. I’ve traveled the world but I haven’t traveled much throughout my own country, my own land. It’s missing. I have the fortune to work with musicians in Havana from all of the provinces, who come and teach us things that we sometimes don’t know. Because given that Havana is the capital, well, everything happens here, the musicians from the countryside come to Havana, and we share and get together and learn. But I haven’t been able to make a trip across and throughout all of my country, only to study. It’s something that I owe myself, that I have to do. I can’t die without doing it.

As you’ve traveled around the world, touring through the United States and Europe, how have you seen your music or more generally your perspective on music and art evolve?

Well, with respect to my music, it evolves just as I evolve and just as my thoughts evolve. My music changes as my experiences change. It’s a reflection of my life, of the things that happen to me. I’m honest when I write music. I don’t sit at the piano and make up things that don’t exist. Everything that happens in my music is an answer to my life as a whole. In that way, my musical evolution is based on my human evolution.

How has your band evolved? I saw your concert in New York in early January. Not only was I impressed by your presence and your voice, but I also found your band’s communication remarkable. How did you meet your musicians, how long have you been playing together and how have you developed your sound as a band?

We’re all a family, a beautiful family of friends. A sincere family. It’s not about, “Hey, we love each other like family,” and then it’s all a lie. No, we’re a real family: we tell each other off, we console each other, we help each other, we give each other advice, we’re a team and we support each other. What happens with my band, is that this connection can be heard. When you’re playing with a band, which more than a band is your friends, and more than your friends is your family, you play with confidence. Because you know that, just by looking into the other’s eyes, you can understand what he’s going to do, how he’s going to play, what’s going to happen. And that didn’t come one day to the next, that’s a connection that we’ve been building bit by bit. We’ve known each other for years, and we’ve been playing together for less—maybe a year and a half, two years—but it’s been easy, because the feelings are mutual.

Are all of your musicians Cuban? Do they have musical backgrounds similar to yours?

Yes, they’re all young Cuban guys. Some are younger than me, others are older, but we’re all young and that’s the most important! [Laughs] Youth, what a divine treasure! And they’re all guys who have their own projects, their own concerns, their own musical goals. Each one of them has something to say to the world.

In terms of saying something to the world, do you have a general vision of what you’re trying to bring to the world through your music? Where does the motivation for your musical work come from?

I feel that I have a vision in life, which is to bring a message, through music, of strength, perseverance and humanism. You know, I’m a woman who has overcome many things, and my music has been the antidote that I’ve found to solve many problems. I think that music can heal the world and I want that to be my legacy in this life. Those who know say that I’ve lived many lives, other lives, and that’s why I’m an old soul. But in the life I have to live now, I want to show the world that music can be a remedy for so much hate, for so much suffering, for so much pain.

If I understand correctly, you practice the religion of Santería, which is expressed in various ways in your music. Can you tell us more about it and explain how it came to be a part of your life?

Santería came to my life through music. I fell in love with religious music, because it has so much to draw from and build upon. Religious music has an impressive rhythmic and melodic richness. Initially, I composed a lot of music for choirs, because that’s what I studied. I’m a choir director, I graduated with a degree in choral direction. I composed a lot—a lot—for choir. In that way my attention was drawn to the combination of classical music with Cuban religious music, and from there grew my love for all of the mysticism that was involved in interpreting and making religious music. That’s where it comes from, yes. After, I asked my grandmother, who is the only Santera in my home, whether I should be a Santera because at the time certain things were happening to me—personal things and spiritual things which I wanted to heal and remedy—and she asked the saints and they said yes. So, with all of the love in the world, my grandmother made me Ocha, made me Yemayá (who is my mother) and Obatalá (who is my father). I am the daughter of the sea and of peace. So they were crowned on my head and today I live with my saints in my home.

Was this recent?

This year will be my third year as a Santera. Yes, I’m not an old Santera, I’m just a little girl in the religion. However, my best friend has been Santera for 23 years, and we’re the same age. She was made Santera at two years old, I was made Santera at 22.

Thinking of your Cuban audience, how did your success outside of the country influence your domestic career?

In Cuba, I had a lot of obstacles to be a musician, to be the musician that I wanted to be. A lot of doors were closed to me. Others were opened, but many were closed, for reasons that are irrelevant … because I wasn’t up to the country’s beauty standards, because I walked barefoot, because I was making the music that I wanted to make. I wanted to play jazz with my own Cuban influences. And I was discriminated against in that sense many times. But this year is an interesting year, even if it just began, because this year, stemming from my international artistic reach and the success that I’ve had in these past years, you know, people have started to pay attention to what I’m doing and to recognize it. And today I’m getting solicited by people who didn’t value me in the least, people who crushed me, people who told me that I would never get anywhere if I continued in the direction that I was working in, people who told me, “If you want to triumph, stop signing the music that you’re signing, get on a diet and lose weight, put on some high heels, and go get a perm and some extensions.” You know? People who tried to change who I am … now they’re calling my home to congratulate me, to invite me to concerts, to recognize my work. So in the end, I think so much fighting bore its fruit, and now in Cuba people are bit by bit starting to better understand Daymé and what she projects as an artist.

I’m happy to hear it. In terms of that development over the past few years, can you tell us how you began to make these international connections, in particular with the Havana Cultura project?

That was a beautiful coincidence. I was called in for an open mic, because Havana Cultura was organizing an event with Cuban singers and with international DJs, and the DJs had the opportunity to listen to many signers and decide who they wanted to work with. So I showed up to the open mic, along with a lot of other people, sang the one song that I was allotted, and left. The act of singing one song meant that you would be chosen or not. I had the luck, to put it one way, that all 10 of the DJs chose to work with me. That was the start of it all, because they were 10 DJs from different countries. There was a Russian, a German, a Swiss, a Chilean, a South African, a Hungarian, an Englishman … I don’t remember but each guy was from a different country with its own culture and its own musical ideas. For Havana Cultura and for Brownswood, it was impressive that 10 people from ten different countries voted for me when they had the opportunity to choose other singers. It was such a big deal that they had to decide that only four of them could work with me because it would have been too many otherwise, they couldn’t make a record of Cuban singers with only one signer. And that’s how it started, the consequence of all of those 10 DJs wanted to work with me, and then they invited me to London for the album launch and then they proposed that I record a session for the first time, a session album, which is the album that’s called The Havana Cultura Sessions: Daymé Arocena. And that’s where this whole infinite journey began. When I say infinite it’s because it’s a spiritual journey, one of personal rejoicing. It’s a divine trip.

That’s a great story. The world is lucky that things worked out that way and that so many have since had the opportunity to hear your voice and be in contact with your work.

Honestly, I think that without that coincidence, it would have been very difficult for me, because I put in a lot of work and a lot of people didn’t believe in me. I think that the people who believed in me were the most humble, of humble soul but also financially humble. That’s why many people believed in me but weren’t able to help me in the way they would have wanted. And the people who did have the power to open doors for me and to give me opportunities simply didn’t do it, and now they have to recognize what they didn’t do at that time.

Thank you, Daymé, for sharing your story with us. I think we’ll leave it there, but before you go, you mentioned your admiration for the musical cultures of Brazil, Cuba and the United States. Can you leave us with the names of some artists from each country who stand out for you right now?

Well, there are many, so many. Too many. I like a lot of people from Brazil. Among those who are still alive I love Djavan, I love Maria Rita, I love Ed Motta, I love Jair Oliveira. There are a lot of young people who I heard in Brazil but didn’t have the opportunity to make a note of. That’s why I feel like I have to go back, again and again. There’s a band called Zuco 103 that I like a lot as well.

Ed Motta and Daymé Arocena share the stage in 2016.

From the United States … imagine! What I like from the United States, right now, is the experimentation. There are a lot of people experimenting. There are people like Kendrick Lamar or Anderson Paak who are mixing jazz with hip-hop. There are people like Esperanza Spalding who is mixing jazz with opera, with classical music. You know, there are a lot of people experimenting, which is a new thing. I think that what I like from the United States is the contemporary experimentation.

How about Cuba?

Hmm. I love Cuban music, in every sense. I think people need to pay attention to young Cubans, to the young jazz musicians who are doing new things, to the young female jazz musicians. There are amazing girls like Yissy García, who mixes jazz with electronic music. There’s Yasek Manzano. There are people like Alain Perez or Havana D’Primera and Alexander Abreu, who mix jazz with traditional Cuban music or dance music, or Interactivo, who are one of those bands who mix all types of popular or dance music from Cuba with jazz, funk and Spanish music, which is very integrated with our culture as well. So yeah … And like always, if we’re talking classic, you have to listen to Chucho [Valdés]. Of course! You have to listen to lots of Chuco.

Yissy Garcia, "Tutu"

Daymé, thank you very much. Good luck with everything this year and with your album release. Have a great day.

Same to you! Have a beautiful day and enjoy it over there.

Chucho Valdés, "Son No. 1"

Original interview in Spanish:

Alejandro Van Zandt-Escobar: ¿Puedes presentarte y decirnos de dónde nos estás hablando?

Daymé Arocena: Hola, soy Daymé Arocena y estamos hablando desde la Habana, Cuba.

Bueno. Sabemos que tienes un nuevo álbum saliendo muy pronto, después de varios discos que ya han tenido mucho éxito. ¿En que Cubafonía es un paso nuevo comparado con lo que ha venido antes?

Lo que sucede con Cubafonía es que es un disco de canciones totalmente mías, escritas con la intención de recrear un poco los ritmos típicos y tradicionales cubanos. Porque lo que sucede es que, por ejemplo, la gente conoce al mambo, la gente conoce al chachachá, la gente conoce muchos ritmos de la música cubana y no saben que son cubanos. Entonces estoy intentando con este disco que el mundo reconozca la música cubana, y a través de mis canciones es un recorrido por ritmos y géneros de la música cubana que son parte de la historia de la música mundial y que, tal vez porque Cuba es una islita en el medio del mar, la gente no reconoce que son géneros nacidos en Cuba.

He notado en sus conciertos esta maestría de varios géneros musicales diferentes. ¿Puedes platicar un poquito sobre tu educación musical? ¿Como has logrado explorar y aprender todos estos estilos diferentes de la isla de Cuba?

Bueno, yo soy música académica. Yo estudié en la escuela de música, en el Conservatorio Amadeo Roldán, y ahí nos enseñan a Bach, y nos enseñan a Mozart, y nos enseñan a Beethoven, y nos enseñan a Brahms y a Strauss y a Mahler y Wagner, pero también nos enseñan los clásicos cubanos. Y en algún momento se tocan los géneros de la música popular cubana, que no se les hace el gran reconocimiento en la escuelo porque la escuela está enfocada más en lo que es la música clásica, pero lo entendemos, lo reconocemos y lo estudiamos. Yo creo que la escuela fue mi primer acercamiento a los géneros de la música tradicional cubana. Y después, la calle, y la vida, me han enseñado lo lindos que son y lo influyentes que son en la vida de cualquier cubano, sea o no sea musico. Osea que, por ahí comenzó mi complicidad con los géneros que me vieron nacer. ¿Y por ejemplo qué sucede? En el caso de la rumba … esos son géneros que uno tiene más cercanos, porque la gente los toca en la calle, los escucha, los siente, pero hay géneros como el changüí que son totalmente autóctonos y están en el final del país, están para Guantánamo, para provincias más alejadas. Entonces uno le pierde el hilo a esos ritmos y yo no los pude abarcar todos porque yo en mi disco intenté poner tango congo, intenté poner rumba antigua, rumba moderna, intenté poner pilón, intenté poner bolero, chachachá, mambo, pero me faltaron muchos. Me faltó el dengué, el nangón, el sucu-sucu, me faltaron muchos ritmos de la música cubana, por poner—¡la conga! Sabes … Cuba es una sabia, es un manantial de música, y yo me atrevería a decir que es una potencia en sentido general. Yo me atrevo a decir que, el que quiere ser músico de verdad, tiene que visitar a lo menos en su vida tres países: Brasil, Estados Unidos y Cuba.

¿Usted ha viajado mucho por la isla para colaborar con músicos, o ha estado más bien basada en la Habana para su trabajo musical?

Es una de las cosas que me debo. He viajado mucho el mundo y no he viajado mucho a mi propria patria, a mi propia tierra. Me falta. Tengo la suerte y la dicha de compartir con músicos en la Habana de todas las provincias, que vienen y nos enseñan cosas que a veces nosotros no sabemos. Porque como que la Habana es la capital, bueno, todo pasa aquí, los músicos del campo vienen a la Habana, intercambian con nosotros y uno se junta y aprende … pero no he podido hacer un viaje a lo largo y ancho de mi país, solamente para estudiar. Es algo que me debo, que tengo que hacer. No puedo morir sin hacerlo.

En términos de sus viajes por el mundo, de sus tornadas por los Estados Unidos y Europa, ¿como ha visto evolucionar su música o sus perspectivas generales sobre la música y el arte lo más ha viajado?

Bueno, en cuanto a mi musica, mi música evoluciona como evoluciono yo, como evolucionan mis pensamientos. Mi música cambia como cambian mis experiencias. Mi música es un reflejo de mi vida, de las cosas que me pasan. Yo soy honesta cuando escribo música. No me siento al piano y invento cosas que no existen. Todo lo que sucede en mi música es la respuesta a mi vida en sí. Así es que, la evolución de mi música está basada en mi evolución humana.

¿Y cómo ha evolucionado su grupo? Vi su concierto en Nueva York en comienzos de enero. Me pareció muy potente no solo su presencia y su voz, pero también la unidad tremenda del grupo entero. ¿Cómo encontró a estos músicos, desde cuando han tocado juntos y de qué manera han ido desarrollando su sonido juntos?

Nosotros somos todos una familia, una familia linda de amigos. Una familia sincera. No es el cuento de, “ay, nos queremos como familia,” y es todo mentira. Nó, somos una familia de verdad, nos regañamos, nos consolamos, nos ayudamos, nos aconsejamos, somos un equipo, y nos apoyamos unos a los otros. Lo que sucede con mi banda, es que eso se siente. Cuando tu estás tocando con un grupo, que más que grupo son tus amigos, que más tus amigos son tu familia, tu tocas confiado. Porque sabes, que solo con mirar a los ojos del otro entiende que va hacer, cómo va tocar, que va pasar. Y eso no se dió de un día para otro, eso ha sido una conexión que hemos ido creando poco a poco. Nos conocemos todos hace años, y tocamos juntos hace menos—digamos, un año y medio, dos años—pero ha sido fácil, porque el sentimiento es mutuo.

¿Sus músicos son todos músicos cubanos? ¿Han tenido recorridos parecidos al de usted?

Si, todos son muchachos jóvenes cubanos—hay algunos más jóvenes que yo, otros menos jóvenes—pero todos somos jóvenes, que es lo más importante [risa]. ¡Juventud, divino tesoro! Y todos son muchachos que tienen sus propios proyectos, sus propias inquietudes, sus propias intenciones musicales. Todos tienen algo que decirle al mundo.

En términos del mensaje que quiere transmitir por su música, ¿tiene una visión general de lo que quiere traer al mundo con su arte? ¿De dónde sale la motivación para su trabajo musical?

Yo siento que yo tengo una misión en la vida, que es llevar un mensaje, mediante la música, de fortaleza, de perseverancia, de humanismo. Sabes, yo soy una mujer que se sobrepone a muchas cosas, y mi música ha sido el antídoto que he encontrado para solucionar los problemas. Pienso que con música se puede remendar el mundo, y quiero que esa sea mi legado en esta vida. Dicen los que saben que ya he vivido muchas vidas, otras vidas, y que por eso soy una alma vieja. Pero en esta que me toca vivir ahora, quiero demostrarle al mundo que la música puede ser el remedio a tanta ira, a tanto sufrimiento, a tanto dolor …

Si entiendo bien, usted practica la religión Santería, lo que se nota de diferentes maneras en su música. ¿Nos puede contar más sobre ella y contarnos cómo vino a ser parte de su vida?

La Santería llego a mi vida mediante la música. Yo me enamoré de la música religiosa, porque tiene mucho por donde sacar y por donde explotar. La música religiosa tiene una riqueza rítmica y melódica impresionante. Yo al principio componía mucha música para coros, porque fue lo que estudié. Soy directora de coros, soy graduada de dirección coral. Y componía mucho, mucho para coro. Por tanto me llamaba mucho la atención la combinación de la música clásica con la música religiosa cubana. Y ahí comenzó mi amor por todo el misticismo que traía entonces el hecho de interpretar y de hacer música religiosa. Y de ahi viene, si. Después, le pregunté a mi abuela que es la única santera de mi casa, que si yo debía ser santo porque me estaban sucediendo cosas—cosas personales y espirituales que deseaba sanar y remendar—y ella le preguntó a los santos y le dijeron que sí, y con todo el amor del mundo mi abuela me hizo Ocha, me hizo Yemayá (que es mi madre) y Obatalá (que es mi padre). Yo soy hija del mar y la paz. Por tanto, los coronó en mi cabeza y de ese día vivo con mis santos en casa.

¿Eso fue algo reciente?

Yo cumplo este año tres años de santo. Si, yo no soy una santera vieja, yo soy una niña de la religión. Sin embargo, mi mejor amiga tiene 23 años de santo, y tenemos ambos la misma edad. A ella la hicieron santo a los dos años, a mi me hicieron santo a los 22.

¿Pensando en su público cubano, de qué manera su éxito fuera del país ha influenciado su carrera doméstica?

Yo en Cuba tuve muchas trabas para ser música, para ser la música que deseaba ser. A mi me cerraron muchas puertas. Me abrieron otras, pero me cerraron muchas, por muchas razones que no vienen al caso. Por no ser del estándar de belleza que se maneja en el país, por andar descalza, por hacer la música que yo quería hacer. Yo quería hacer jazz con mis influencias de Cubanidad. Y fui discriminada en ese sentido muchas veces. Pero, este año es un año interesante, aunque recién comienza, porque este año, a raíz de toda la proyección artística internacional y el éxito que he alcanzado en estos últimos años internacionalmente, tú sabes, la gente ha comenzado a prestarle más atención a lo que hago y a reconocerlo. Y hoy me llama la atención que gente que no me valoró ni remotamente, gente que me aplastó, gente que me dijo que nunca iba a llegar a nada por la línea que estaba trabajando, gente que me decía, “Si tu quieres triunfar, deja de cantar la música que estás haciendo, haz una dieta y baja de peso, ponte unos tacones y haste un relaxer en el pelo y ponte extensions.” ¿Sabes? … gente que intentó cambiar mi propio yo … hoy me llaman a casa para felicitarme, para invitarme a conciertos, para reconocer mi trabajo. Así es que, creo que en final, tanta guerra tuvo fruto, y ya en Cuba poco a poco se va entendiendo mejor a Daymé y a lo que proyecta como artista.

Me alegra mucho oírlo. En términos ese desarrollo en los últimos años, ¿nos puede contar sobre como empezó a hacer esas conexiones internacionales, en particular con el proyecto Havana Cultura?

Esa fue una casualidad muy linda, porque a mi me llamaron para hacer un open mic, porque Havana Cultura estaba organizando un evento con cantantes cubanas y DJs internacionales, y los DJs tenían la posibilidad de escuchar a muchas cantantes y al final decidir con quién iban a trabajar. Y yo me presenté al open mic, como se presentó mucha gente, canté una canción que fue lo que me tocaba, y me fuí. El hecho de tocar una canción podía significar que te escogieran o no. Yo tuve la suerte, por decirlo de alguna forma, que me escogieran para trabajar los diez DJ. Eso fue el principio de todo, porque eran diez DJ de diferentes países. Habían Ruso, Alemán, Suizo, Chileno, Sudafricano, Húngaro, Inglés … no recuerdo pero cada chico era de país distinto con cultura distinta con ideas musicales distintas. Para Havana Cultura y para Brownswood, era impresionante que diez personas de diez países distintos votaran por mí, cuando tenían la posibilidad de escoger a otros cantantes. Tanto fué así que ellos decidieron que solamente cuatro iban a trabajar conmigo porque era demasiada gente, no podían hacer un disco de cantantes cubanas con una sola cantante. Y por ahí empezó, por esa repercusión de los diez DJs que querían trabajar conmigo, fue que ellos decidieron invitarme a Londres para el lanzamiento del disco y proponerme grabar por primera vez un session, un disco session, que es el disco que se llama The Havana Cultura Sessions - Daymé Arocena y a partir de ahí comenzó todo este viaje infinito de trabajo. Cuando digo infinito es porque es un viaje espiritual, de regocijo personal. Es un viaje divino.

Es una historia linda. Creo que el mundo tiene mucha suerte que salió así y que por eso somos tantos en el mundo que pueden oír su voz y estar en contacto con su arte.

Sinceramente, yo creo que sin esa casualidad de la vida, hubiese sido muy difícil para mí, porque hice mucho trabajo y mucha gente no confió. Yo creo que la gente que confió era la gente más humilde, humilde de alma y humilde monetariamente también. Por eso hubo mucha gente que confió pero no me pudo ayudar como hubiesen deseado. Y la gente que sí tenía el poder en la mano de abrirme puertas y de darme oportunidades simplemente no lo hizo, y ahora tienen que reconocer lo que no hicieron en ese momento.

Muchas gracias por compartir con nosotros su historia. Creo que lo dejaremos ahí, pero para terminar, usted habló de su admiración para las culturas musicales de Brasil, de Cuba y de los Estados Unidos. ¿Nos puede dejar con los nombres de unos artistas de cada país que sobresalen para usted en este momento?

Bueno … ahí son muchos, muchos. Demasiados. A mi me gustan de Brasil mucha gente. De los que aún están vivos me gusta mucho Djavan, me gusta mucho Maria Rita, me gusta mucho Ed Motta, me gusta mucho Jair Oliveira. Hay mucha gente joven que escuché en Brasil que no dió chance a tarjetear. Por eso siento que tengo que regresar una y otra y otra vez. Hay un grupo que se llama Zuco 103 que me gustó mucho también.

De Estados Unidos, imagínate tú! Me gusta de Estados Unidos, right now, la experimentación. Hay mucha gente experimentando. Hay gente como Kendrick Lamar o Anderson .Paak que está mezclando jazz con hip-hop. Hay gente como Esperanza Spalding que está mezclando jazz con ópera, con música clásica. Sabes, hay mucha gente experimentando, cosa nueva. Yo creo que de Estados Unidos me gusta mucho la experimentación contemporánea.

¿Y unos de Cuba?

Hmmm. A mi me gusta mucho la música cubana, en todo sentido. Creo que hay que prestarle atención a los jóvenes cubanos, a los jóvenes jazzistas que están haciendo cosas nuevas, a las mujeres jazzistas jóvenes. Hay chicas fenomenales como Yissy García, que mezcla jazz con música electrónica, o Yasek Manzano. Hay gente como Alain Perez o Havana D’Primera y Alexander Abreu, que mezcla jazz con música bailable o música tradicional cubana, o Interactivo, que son bandas que lo que hacen es mezclar todo tipo de influencias populares o bailables o danzables cubanas, con jazz y funk y música española que la tenemos muy agregada en nuestra cultura también. Pues yá ... Y como siempre, con lo clásico, hay que escuchar a Chucho. Claro que si. Hay que escuchar mucho a Chucho. A los clásicos también, como no?

Daymé, muchisimas gracias, y le deseo mucha suerte con todo este año, y con el lanzamiento del disco. Que pases un buen día.

¡Igualmente, que tengas un lindo día y gózalo por ayá!