Contributor Saxon Baird has been documenting the process of producing and researching his forthcoming Afropop Hip Deep program Dread Inna Inglan. The following was originally published via Saxonbaird.com.

In some of the early research I did for “Dread Inna Inglan,” I became sort of fixated on who was the first one to utilize the “fast chat” style of toasting. For those who don’t know, “fast chat” is exactly as it sounds; a sped-up style of toasting that is very similar to early 80s rapping. I suppose it could be considered sort of proto-rapping….but that’s a whole other road altogether to go down.

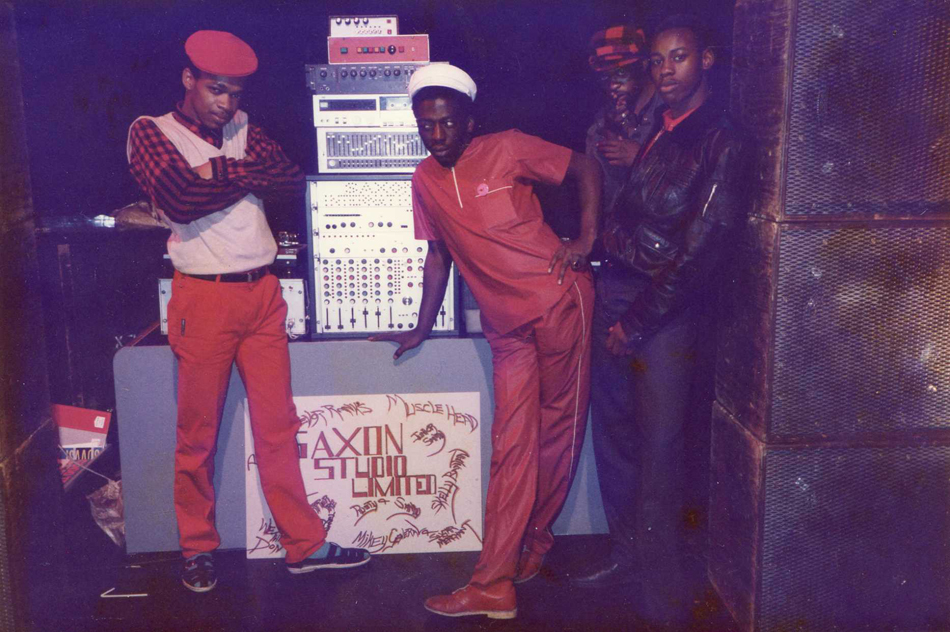

Most sources seem to point to the groundbreaking UK soundsystem Saxon Sound as the innovators of “fast chat” with DJ Peter King as the first one to use the style, with other Saxon Sound DJs like Smiley Culture, Tippa Irie and Papa Levi following suit. When in Jamaica, I wanted to get some commentary from anyone I could talk to on the fast chat style. I was looking to make the connection between UK DJs and soundsystems and ultimately showcase the influence that British-born Jamaican DJs had on the Jamaican DJs back on the island.

A major aspect of my program that I want to tease out is how British-born Jamaicans looked to the the music and culture popular on the island of their parents birth (Jamaica) and how that played a role in shaping the identity of a whole generation of those who were raised culturally Jamaican but born in the UK.

The fascinating aspect about the “fast chat” style is that it's an example of how when reggae and dancehall grew out of these communities in the UK, it really became something of its own. DJs, soundsystems and producers still looked to Jamaica for influence, but instead of just imitating, they moved the music forward, progressing and developing it into something that spoke and resonated with their own experience in the UK both topically and stylistically.

As Les Back notes in New Ethnicities and Urban Culture:

In Jamaica the emergence of toasting was characterized by a schism in “roots culture” between the political programmes of singers and toasters/DJs: “Jamaican DJs steered the dance-hall side of roots culture away from political and historical themes towards ‘slackness’: crude and often insulting wordplay pronouncing on sexuality and sexual antagonisms” (Gilroy 1987: 188). The ascendancy of slackness in reggae music led to the waning of political emphasis in Jamaican reggae, which shifted from the engaged politics of Rastafari to an assertive individualism. It was this turning away from politics in Jamaica that opened a space for English MCs such as Tipper Irie, Papa Levi and Leslie Lyrix to take the musical and oral practices of the sound system and change the agenda on the microphone. The result was a fusion of the assertive style of the “slackness” DJs (Yellowman and General Echo are prime examples) with a grounded dissection of the social consequences of Britain’s economic and political crisis for young black Britons. New styles emerged that were much more than plagiarized versions of their Jamaican counterparts. Tipper Irie: The three wise men are Daddy Colonel, Papa Levi and me. If you want to learn the ‘fast style’ Check Levi If you want to roll your tongue Check Colonel T You want intelligent lyric Check Tipper Irie … one of the most important innovations in England during the mid-1980s was developed by Peter King in what came to be known as the “fast style” or “rapid rappin”. This was an important development because it meant that English MCs were no longer dependent on their Jamaican counterparts for inspiration. As Peter King explains: “A lot of English MCs was chatting like yardies, they weren’t trying to be original. I heard a lot of MCs copying and pirating, not entire lyrics – just the style. It all became rather the same … I did the fast style in 1982. People was already coming to Saxon but they used to love the fast style … People from other sounds used to say the “fast style” was bad. They come to me and say “drop it in now”, in the dance so that they could hear it. Everybody was doing a style off a it – just said, well, cool runnings, at least they know who originated it.” (Echoes, 4 May, 1985).

As Back explains, new themes emerged in the UK scenes that were rooted in the socio-economic experience of young, black Britons. And with that, a new style of vocal delivery emerged. To connect the dots and showcase how this style in turn influenced Jamaican DJs would be to reveal a sort of real-life example of how, through the music, a diasporic community was able to communicate back to its place of origin in a way that had a real, on-the-ground effect.

The influence seems to be there, but did these Jamaican producers and DJs see that influence and acknowledge it themselves? Or was it something of a coincidence that just as this style of vocal delivery was bubbling up in the UK soundsystems that it begin, eventually, to appear on dancehall records being cut and recorded in Jamaica as well?

Of course, this immediately ran into problems. If the likes of British-born Jamaican DJs like Smiley Culture and Tippa Irie with their rapid fast chat style were influencing DJs in Jamaica, no one I spoke to was ready to admit it. In fact, in my research so far, I have yet to come across any interview from a Jamaican DJ or producer really, fully admitting this influence (let me know if you’ve have!).

When in Jamaica, I was fortunate enough to speak with legendary producer King Jammy, who commented a bit on the UK sound systems in the 80s and 90s. As you will see from the excerpt of my interview below, he spoke fondly of the UK soundsystems and even acknowledged that British DJs may have influenced some DJs back in Jamaica. But then he was quick to point out that Jamaican DJs were “fast chatting” first. Here’s the excerpt which should be published in full at a later date via Afropop:

S: So going back to the influence of /if any English DJs from the UK and sound systems and producers, do you feel like UK DJs and soundsystems were influencing Jamaica at all, or do you think only Jamaica was influencing the UK?

KJ: No, well it goes both sides because even the sound systems in England they are mimicking sound systems in Jamaica. In those days I used to cut dubs for sound systems in England and whenever I go to England, I used to visit dances and those dances were much more vibes-y than the dances that used to be in Jamaica.

S: Can you talk about that a little bit more? Like tell us about who were you cutting dubs for?

KJ: There’s a sound system in England called Fatman. I used to cut for various, but Fatman was my main sound system that used to support dubs…I would go to dances where Fatman played all over England and the countryside, midlands. Those dances are like a football match, people are cheering for your sound like you’re going to a football match. And you see people in the audience cheering for their side. That’s how it used to go in England back in the day, especially when you have a clash dance.

S: Sounds fun!

KJ: Yeah, lots of fun.

S: So how is that different from what was going on in Jamaica during this time? Was it just not as lively?

KJ: Jamaica was like…back in the day people used to hold onto them girl and dance, and that didn’t really give them time to generate energy to vibes up the whole place, know what I mean? It was like a personal thing.

S: Sure. Did you prefer more of what was going on in England?

KJ: I like the excitement and the dance, the excitement and people are getting wild and cheering. I prefer that excitement.

S: So you say it was more like the sound systems that were different? And maybe influencing…

KJ: Yes, some of the DJs from England were influencing some of the DJs in Jamaica.

S: Like Smiley Culture?

KJ: Smiley Culture and a couple of DJs. They were doing more speed rapping at a time than the Jamaicans. Like Jamaicans would speed rap but then stopped. Then the English DJs picked it up and carry it along somewhere.

S: When you saw artists do that in England, did you then start seeing artist doing that in Jamaica?

KJ: No, it was being done in Jamaica first. Speed rapping was in Jamaica first. And then it faded out and they picked it up in England and took it to another level.

S: Oh okay, alright. Who were some of the first artists doing that in Jamaica that you heard?

KJ: Brigadier Jerry was one of them who was doing it. Chaka Demus was doing some speed rapping…(pauses)…quite a few DJs.–

As you can see, Jammy couldn’t really pinpoint for me who was speed rapping or utilizing the “fast chat” style in Jamaica first. He mentioned Brigadier Jerry whose toasting style was speedy for the time but not like the DJs of Saxon Sound. (Side note: I hope to interview Brigadier at some point about this. Rumor has it he lives in NYC and has for some time)

http://youtu.be/MhFXjK8tOOs

In all my other interviews in Jamaica, no one could explicit point to the artist(s) who started with the speedy style of toasting in Jamaica as a predecessor to the “fast chat” style of Saxon Sound. Some mentioned Ranking Joe, General Echo and as Jammy mentioned, Brigadier Jerry. Nor was anyone willing to give much credit, if any, to the possible influence that these UK DJs had on Jamaica.

And that’s kind where my search ended… thus far. When I go to England later this year, I plan on getting thoughts from Saxon DJs like Tippa Irie on whether or not they felt they were influential on Jamaican DJs. I am pretty sure I know what they will say.

In the end, who influenced who probably doesn't really matter. The music clearly acted as a medium through which communicate that was rooted in a culture that those on both sides of the Atlantic were steeped in. It allowed those in Britain to fuse the disconnection caused by their diaspora. And in Jamaica it showcased not only the experiences of those living abroad, but the ability that the music they were creating on the island to resonate in a completely different environment and in communities far from its origins (much as Bob Marley was able to show through his success abroad prior to the soundsystems of the UK).

(special thanks to Kate Bolgar Smith for finding the Les Back quote and sending it my way)