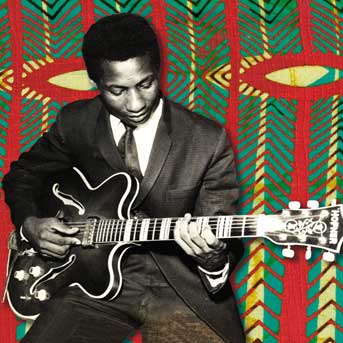

While in Ghana in the spring of 2013, the Afropop team spent a number of days with legendary composer, arranger, guitarist, and bandleader Ebo Taylor. Still active—very active!—at 77, Ebo gave us an education on highlife and Afro-funk, a genre he helped to create it he late ‘60s and early ‘70s. In the first part of a lengthy interview, Banning Eyre, Sean Barlow, and Mark LeVine talk with Ebo about his beginnings, the advent of James Brown, and the creation of Afro-funk.

Banning Eyre: Ebo, let’s go back to the beginning. Tell us about your family, where you grew up, and what the early years were like.

Ebo Taylor: As a matter of fact, I grew up in Cape Coast, 20 kilometers from Salt Pond, where I live now, and Cape Coast is about 120 kilometers from Accra. They are Fantes—Fante-Akan. My father was a schoolteacher and a keyboard player. He played organ in the church. There was an organ in the house. I was born in 1936, so those were the Hitler days. You lived in fear of being bombed. In the night there’s a blackout. So during the four years before they surrendered--that is, between 1940 and 1945--you were always distressed by a possible attack by the Germans. So everybody lived under some kind of fear, and we prayed a lot. My mother was a baker, you know. She baked cakes and bread for sale. At the same time, she was a highly motivated Christian. In those days, a school teacher is one of the celebrated people in town, because he’s been able to be intellectual, and he imparts this knowledge to children. So they looked up at my father as a good man who would always advise. And his wife is good to advise all the women. When there are quarrels, it’s brought to the house.

But then, whilst I grew up, I was also learning, listening to the organ and I followed my father to the church, and listened to the choir. And gradually I became a member of the choir, before the age of 14. I think that accelerated my interest in the minor key. Because the Catholics sung all their chants in the minor, you know [SINGS “KYRIE ELEISON”]. So I think got stuck in mind, you know, the minor mode.

Ebo Taylor and kids at home in Salt Pond

B.E.: That’s beautiful.

E.T.: The minor mode—I think that got into me so much that later on, when I went back to explore the minor key, I got it easily. But this time, with the blues, and the Americans highly involved music, and the rhythms in Africa, I tried to make sounds that will click and make people dance to the minor mode.

B.E.: You told us how you heard the church music, but I assume by then you were hearing traditional music also, music that was there all along.

E.T.: That’s right. That was all around, yeah. When there are funerals and festivals, your mother takes you to the funeral and, you know, you hear people singing this kind of adenkum, and adzowa and ampetampa music, music with only drums, no accompaniment. And music that is very common to the fisherman, the farmer, they will sing as he prepares the net, or as he weeds in his farm. So this is common type music that everybody hears, you know, at funerals. Even in the house, your mom might start singing that kind of song. But it’s all in the minor mode. But when the British came and colonized this country, I think, there was an invasion also of this major, Westminster Abbey kind of music, written in the major key, like [SINGS HYMN "OH GOD OUR HELP IN AGES PAST."]

So, Ghanaians, naturally, adopted that kind of harmony and melody, and it became part of our lives. So when the composers of highlife wanted to compose highlife, that is what it reflects more. Almost all the highlifes are in a major key. Only a few are in a minor key. And then, you can hear, even C.K. Mann’s highlife sounds like that. It goes back to the tonic, it’s a perfect cadence. So there’s no other way of composing highlife but resolving it in the major key. Until later on, when Ghanaians tried exploring the traditional music.

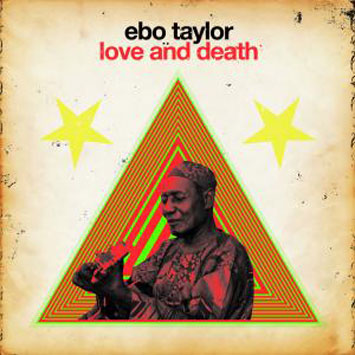

Like I tried to write the song "Love and Death" in English. "Love and Death" originally says, Odo o Yewu, that means, “If you love, you can die; death and love are together.” Odo o Yewu…it can lead you to your death. You know, it’s an old philosophy of the Akans. So most compositions reflected that philosophy and I think I also did, to exploit the strength of this philosophy, while concealing its limitations by putting it in the same vein that I hear…the 3-4 progression [meaning alternating between the 3-minor and 4-major chords of a key]. It sounds like minor, but you are not really in the minor mood. I don’t know, if our ancestors knew about the minor or the major modes, but their compositions were like that naturally.

B.E.: They knew in their ears. They probably just didn’t call it that.

E.T.: If I sang an Asafo song—when we go to Salt Pond, you will hear an Asafo song [“Ayesama.”] The Asafo is an integral part of the state, you know, the Fante…the chief’s house. They have the Asafo as the guards, the military attaché of the chieftaincy. So, they are armed with knives, and you know, we don’t use bows in the south…we are armed with knives and we call them the Asafo. But they have music, you know, like the military form of music, they also have their music to inspire. When they go into war, they sing; when they fight, they sing. And this kind of music is called Asafo music. You see, it may be an interrupted cadence, but it goes back to the minor mode. And when you think of the women’s aspect, the women’s version of the same local group, they sing songs like [SINGS]. The philosophy in that is, if you keep drinking, how can you look after your children? That’s the women saying that to their men. And it’s all in the minor mode. It was the British who converted the minor mode into the major mode.

B.E.: And this affected early highlife, right?

E.T.: I will try to explain the prelude to highlife. The guitar was the fundamental, you know, with the singer, because there was no other instrument: there was no bass. The guitar expressed all the accompaniment, whilst providing the rhythmic propulsion and the bass line.

This is the pattern that was sort of available to the bands that had just the rhythm section and this guitar. If they want to modulate, you know, they tie just a piece of something, like a capo, but they would use a pencil or a piece of stick, and this was how they tuned their guitars to suit the vocal range of the singer. So someone who wants to perform like:

[PLAYS CHORUS TO "LOVE AND DEATH"]

You can see, you can realize, this is typical highlife, African song, you know. It’s harmony, the third, you know, the mediant, and the subdominant, the four. So, as I play in the key of C, I play an E minor to F major. You know, sometimes I add the sixth to it, if I have to improvise, you know.

B.E.: So the E-minor chord is standing in for the C chord.

E.T.: Yes. Sometimes it gives me the feeling that it’s the major 7th.

B.E.: Yeah, it is a bit jazzy in that way.

E.T.: So I use both in the harmonies. If I have to play the E-minor, I could add a C.

B.E.: Ah, the 6th.

E.T.: Yeah, the C, to augment it. It’s great!

B.E.: Yeah it’s beautiful. It’s really open sounding. You just want it to go on and on.

E.T.: So that kind of feeling; it has a minor feeling, but it’s not in the minor key. You won't write this in E minor, or C minor. It is in C, but you have an E minor and F major. And that F major is also…PLAYS. That’s a major 7th, you know. I don’t know the basis of the harmony.

B.E.: Now you say you don’t know the basis of the harmony, but anyone could hear that and know right away: “That’s highlife music,” because of that harmony. It’s very distinctive. Do you know any traditional music that uses that kind of harmony that would have been there before?

E.T.: Yeah, before the guitar, we had just the vocal and drumming. And they were singing the same songs.

B.E.: Okay, so that harmony was already there in vocal music.

E.T.: Already! It’s culture. It’s laid back. But its exploitation depends on the performer.

Mark LeVine: But the actual scale, the more pentatonic scale is like on the gyil (xylophone) or on even the seprewa (lute) or any of the traditional instruments that don’t have the semi-tone going from E to F?

E.T.: No, they don't have that.

M.L.: But the singers always sang it. So it’s just interesting that for hundreds of years, people would sing semitones, but the instruments were only playing, more or less, pentatonic, except maybe the goje [traditional violin of the north].

E.T.: In African music, I think the instruments were designed to accompany the vocal range, the texture of the vocal music. It is the other way round that there is the instrument before the composition. But these compositions were there before the entry of the guitar, which was the first instrument to be in the orchestra. So the guitar is also like that. This song was there before they invented the guitar.

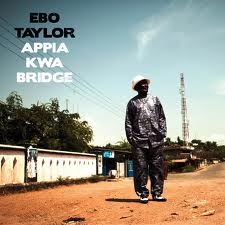

[PLAYS HIS SONG "NSU NA KWAN (THE RIVER AND THE BRIDGE)"]

The philosophy in this song is that the river was there before the bridge. So the river is the eldest, because that was created by God. The bridge is manmade. That’s the wisdom in the composition. You can never be older than your father. The wisdom is with your father. That song is on my album Appia Kwa Bridge.

M.L.: Once you have this beautiful arrangement, then the horns add a whole other layer. And then you have the drums, which to the ears of a lot of Westerners, are never on the one.

E.T.: Yeah, and the drums are also improvised. You know, like to the taste of the drummer. The rhythms might be going, the metronome saying: “pid-im, pid-dim.” But it’s never on the one. So we have to explore, the drummers explore the most,\ enhancing patterns to go with the song.

M.L.: And the horns, how do you arrange those horns, what makes the horn arrangement unique to your style?

E.T.: Yeah, it’s the jazz in you, and you know, the classics. You have to get some jazzy thing to match. But it's that improvised form. You imagine the trumpet player would have to play. You know, or a clarinet or any other instrument. But, you know, it’s an improvised form.

M.L.: You’re improvising these solos, and then when you get one you like, you write it down and chart it?

E.T.: Yes, of course, what I think is more appropriate.

M.L.: So you once talked to me about Miles and Coltrane. Where did their influence fit in to your natural improvisation? Because that fluidness in that line you’re singing reminds me of Coltrane—that constant movement over the pulse.

E.T.: Yeah, that’s right. That is the jazz exploitation. You feel like you are playing in a jazz groove. So if a jazz musician would have to express… PLAYS THE CHORDS AND SINGS LINES OVER. You know, I write that, and give it to the horns to play.

B.E.: When you’re writing a song like that, and does the brass line just come to you, or do you go through a bunch of ideas before you find the right one?

E.T.: I don’t think so, I think I’ve heard enough to know. It’s just like a piece of language you carry around. You listen to it and you know. You sing something today, the next day it becomes parts of you. So, to express it, you know, depends on how much you’ve heard, how much you’ve learned from it.

B.E.: But that particular line for example. Once the song was ready, did it just come to you?

E.T.: Yeah. If I was expressing it in jazz, that’s how I would do it. The way I would play if I was a trumpeter. It’s years of appreciation.

B.E.: And later, when you get to your highlife compositions and even those melodies that we were just talking about with "Love and Death," that was already kind of a merger with major and minor, right?

E.T.: That’s right.

B.E.: But that same merger of major and minor is something you get when you listen to the American blues. It also has that quality. So tell me about your introduction to American music. When did you first hear it, and how?

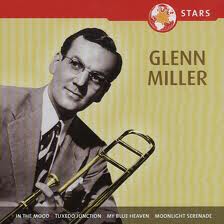

E.T.: Well, the first to emerge was the 12-bar blues. There was that Glenn Miller song called “In the Mood,” and that’s what was very common in American music. The progressive music, progressive jazz came much later. “I’m in The Mood for Love” and all those songs. But the first to come to Africa and Ghana was the 12-bar blues.

B.E.: That’s the 1940s?

E.T.: Yeah, I heard it in the 1940s, 50s.

B.E.: So you were like 10 years old. You were hearing this on the radio.

E.T.: Yeah, I was listening to Glenn Miller, you could go to movies and watch “The Sentimental Journey.” And they had these orchestras and we had the Betty Grable's. It was all part of our libraries. That’s what we referred to. That’s what we’d been seeing.

B.E.: So you heard the blues, but filtered through jazz. You’re hearing Glenn Miller, not some old guy with a guitar from the Delta in Louisiana. You’re hearing it as it came to the city, smoothed out by the horn sections and all that kind of stuff.

E.T.: And sometimes we also listened to the cowboy music SINGS, but I was still young when it faded out. When I was growing up, it was the progressive jazz, like ‘I’m in the Mood for Love,’ and, you know, ‘This Can’t be Love’--that was coming out. But the actual blues, like…I forget some of these titles. But the actual blues was also very common also in Ghana. You know, people would say they are singing American blues. [SINGS IN BB KING MODE]. That kind of music, that’s the blues. So when James Brown started…I was about twenty, between twenty and twenty-one. I heard James Brown, Cliff Richard, Little Richard and some of these American musicians. And I started copying their music, you know.

B.E.: What instruments did you play then?

E.T.: I was still playing the piano, you know, trying to play the 12-bar blues.

And we thought that was hip. ‘Til we started playing in the band, and then Charlie Parker appeared on the scene, and the 12-bar blues vanished, and the inspiration was, you know, SINGS BEBOP. And it was more rhythmic, so, we all learned to play that, without knowing actually what the harmonies were. We were not developed yet to know the harmonies, but we tried to catch the melody structures.

I had been to college, when I was 14, so at college I met some guys who were playing guitar, and I got fascination out of that. So I tried to start to learn to play the guitar and abandon the piano, the organ. So I got to learn the guitar. Then I got into a band that played highlife. But sometimes in the middle of the show you had to play a waltz, a quickstep, the ballroom dancing the English had introduced to us through colonialism. So you get to play songs like “Love, Here’s My Heart" with very little knowledge. You try to play the chords, but it’s not going. LAUGHS. It was not until I grew up and got into a proper orchestra that I saw the chord sheets. For about a year I was playing in a band, and this song… SINGS A SWING SONG…What is the title of this song?

B.E.: It’s a blues. I recognize it but I don’t know the name of it.

E.T.: I’ve forgotten the title. And then I heard a proper orchestra play it, and I went to see the sheet. It was quite different from what I was playing! So I started learning from sheet music, and I joined a proper orchestra, like the Broadway, when I was about 20, 21. I was born in 1936, so at that time, I was about 21. I joined the Broadway Band as a guitarist. And then I could look at the chord sheet and play it without knowing what makes me play that, why I should play this chord. Then I wanted to know why I had to play this chord! So I went to college in London, Eric Guilder School of Music, to learn intermediate and advanced forms of harmony. And then I moved away from the primary chords, to playing this kind of augmented 5th, you know. I mean, the chord sheet, which sounded great to me, but I didn’t understand it until I was made to learn much more about harmony and orchestration.

B.E.: What year did you move to London?

E.T.: In 1961, 62.

B.E.: You know, in so many stories of musicians in Africa, the parents are not supportive of a musical career. But your parents obviously helped you because you went to London as a young man. How did that happen?

E.T.: Yeah. My parents knew, for example, that you could be an international musician if you study. Okay, so if that’s what you want to do, then go to England and study it properly. Go to a school and then they teach you the music. So I went to Eric Guilder School of Music. It’s in the West End. But it was sponsored at that time, by the Ghana government, the Ghana High Commission Education Attaché, in London. When they found out that I had passed through Cambridge overseas examinations, music section, you know, when I had passed with credits, they said, ‘Okay, why don’t you continue to go to music school?’ So they gave me financial assistance to go to the school. Music schools are very expensive, and I went to a private music school, Eric Guilder.

At that time, Fela was in Trinity College, and we became friends, both of us from West Africa, you know, and we had a common interest in highlife, and then we also had the desire to become a Miles Davis, a Charlie Christian, a Kenny Burrell. So we had the same moods, and we met quite a lot.

B.E.: What do you remember about Fela then in those days?

E.T.: Oh, he was frisky! Fela wouldn’t allow any joke on him. I mean, like any Nigerian, he’s frisky and arrogant—excuse my language. So, it was very hard to move around with him. But my interest was, he was ahead of me one year at the Trinity College, and he could teach me a bit here, about harmonies. He might tell me, “Taylor this is the flattened fifth chord.” You know, he became a good friend of mine.

So whilst in London, I learned about composition and arrangement, jazz and pop. So when I came back home, I was arranging the highlife in a more conventional styles, let’s say with two, three trumpets, and four reeds, so that I could have counterpoint in my music. When James Brown and others came with the funk, we all turned again on the minor mode, you know. We all got with the mood again.

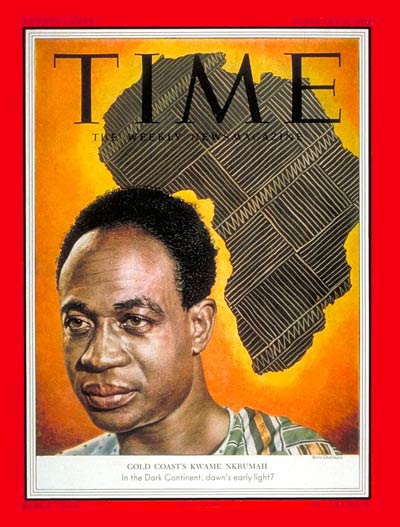

B.E.: Before we get into the funk, a little more about London. You became friends with Fela because you are both West Africans. But there were a fair number of West Africans, weren’t there? And you were getting support from the Ghanaian government. Nkrumah’s government actually believed in music as a career, enough that they were paying for people like you to go study music in London.

E.T.: Yeah, because Nkrumah had some kind of special feeling about the development of culture, of the arts. His government was very, you know, susceptible to demands like that. If you want to study the arts, he gave you the same opportunity like you would give to American student.

B.E.: So were there a lot of you there in London. A lot of West Africans?

E.T.: We were about six at that time. Teddy Osei of Osibisa was there, and

Eddie Quansah who later on played with Bob Marley, and then Johnny Nash. And then they came to the States. Well, I don’t know where they are now, but I came back home, to support the highlife.

B.E.: So it sounds like those musicians who were given that chance to go from Ghana to London, they didn’t just waste it, they all went on and did things mostly. They became significant musicians.

E.T.: Yeah, that’s right. It was good in that day, they were giving opportunity to study. They excelled in their fields. Like Osibisa was formed by a Ghanaian and they toured, you know. It wasn’t a waste! I came back to Ghana to teach, I arranged for musicians like Pat Thomas, C.K. Mann, Gyedu Bley Ambolley. I wrote music for Jewel Ackah, A.B. Crentsil and other musicians.

B.E.: So if you hadn’t gone to London and learned how to write and arrange music, it wouldn’t have been possible to enrich and modernize highlife music the way you have done.

E.T.: Yes, it’s true. Because, what else could I have done? Because there was these innovations, gathering from jazz and the classics. For my major, I studied Dvorak’s New World Symphony in detail at the school of music, at Eric Guilder. And whilst I was doing my overseas examination from Cambridge, my major was the D-flat Symphony by Mozart. So you study in detail, and you know what the oboe would be playing, and you know what the bassoon would play at this point. And you are able to recognize the passages. They put you to an audio test, where you recognize intervals, you know, different forms of chords. You have to study to an advanced level to be able to arrange music like Jim Lally, Cole Porter, and other musicians.

M.L.: You talked about you and Fela, and I’d like to hear more about how you were developing your musical concepts in London. But also, were you playing with British guys, were you playing with Americans who were there? Who were you interacting with? Who was in the local scene?

E.T.: Yeah, sometimes you get hired by, you know, another musician, a British or American, and you go and sit in as a player. But I never stayed like a member, you know. But I think I played with different groups at the Flamingo, and the Ronny Scott Club, where we played jazz, you know. And Fela or Mike Farana, also a Nigerian, might sit in with me. I did play with some American musicians who came to London. They might not come with their guitarist, so they would hire me. So I go and play the sheet music and get paid, that’s all. Maybe I might have the chance to express, you know, ad libs, or I might just be limited to playing the accompaniment. But we had the chance to mix even with Jamaicans, you know, people in the calypso vein. And sometimes you get involved with the reggae people.

B.E.: It was ska in those days, rocksteady, wasn’t it? They didn’t have reggae until ’61 did they?

E.T.: Yeah, at that time of “My boy Lollipop.” That was ska.

M.L.: You know, John Collins has this wonderful theory about the circulation of people and culture. The slaves get taken to a place like Jamaica. Their children or grandchildren come back as part of military bands, and then they re-shape Ghanaian music, and then it goes back to Jamaica and helps shape reggae, and then it comes back… it’s a kind of a circle.

E.T.: Yeah.

M.L.: So what was it like when you met a Jamaican musician who might look like your cousin, right, because maybe their ancestors were taken from this region. Can you just describe a little bit, what was it like to interact with these musicians from Jamaica who were related to you, yet had been separated for a century. Did you feel a natural affinity? Did you guys feel related musically and even ethnically?

Lord Kitchener

E.T.: Culture also separated us. They get used to a certain, you know, type of culture, which we are not familiar with, and that separates us. And sometimes they take the African as a little bit backward. Because the Caribbean guy, he’s being tuned to a more enlightened society. So he thinks you coming right from Africa, we don’t share the same plates, you know. So sometimes we feel downtrodden, like they don’t respect the African musicians, although you play almost the same thing, he thinks he’s more hip than you are. And we could not help but notice that culturally. But there are some moments that they recognize that we have some originality that they don’t have. And they might want to be like us. They’re also coming from West Coast of Africa, and the music is coming with them. Sometimes we feel that their music is like maybe we play with similar groups like Lord Kitchener, or you play the calypso because you’ve heard it back home and you are more acquainted with the calypso. The guys who play calypso in Jamaica feel that you have to learn from them, but we also feel that we have the original rhythm. So sometimes they have to learn from us. And finally, they do have to learn from us. They ask you, "What is the meaning of this?" Maybe the conga player might have expressed SINGS RHYTHM, extra notes into it. So he gets to know that you are ahead of him, and more original that he is. But all the same, the social attitude is that he’s hipper, because he stays with a more respected society. You are coming from the jungle.

B.E.: That’s interesting. But at a certain point, the serious musicians start to understand that actually you have something something closer to the source …

Aaron Sukura and Ebo Taylor (Eyre 2013)

E.T.: The original. That's right. For example, after the Ghanaian independence [1957], people started looking at Ghanaians differently. The awareness that we are free from colonialism. They are free from slavery, and we are also free from colonialism. So they give you the amount of respect due, you know, as a Ghanaian.

B.E.: That's fascinating. What year did you come back from London back to Ghana?

E.T.: 1965. Yeah, I always wanted to come back to my hometown, go back to Salt Pond, you know and be with my people. Despite the social and economic pressure, you really want to come back home. While all the major content of my coming back home was also to teach, you know, and to disseminate the information out to the younger musicians, you know. For example, before I left for England, no musician was called a musician, you called them, you would call them ‘band boys’ and other appellations that put me off. So when I came back, I started calling them musicians, to make themselves known as musicians, not band boys. So now they call them musicians, and what they called a band practice is now a rehearsal, and thanks to the language we brought back home, there were major changes.

B.E.: So it's 1965. It had been four years, and you come back with this education. And you are now a powerful person, in demand with serious musicians, because they know you have something they need. You can arrange the brass, you can make things right, get it all to really lift to a higher level, right?

E.T.: Like you know, I still lament about the music education in this country. I always think that there are no faculties to teach popular music. When I talk about popular music, I mean jazz and classics. There are no schools, not even the University of Ghana is providing the syllabus for it.

B.E.: We were there with you yesterday. We saw them teaching traditional music, but they’re not teaching this?

E.T.: They’re not teaching jazz, you know. None of the educationists there will talk about Miles Davis. No. They prefer talking about Koo Nimo [the great Ghanaian palm wine guitarist], or more traditionalists. To enhance the knowledge that Koo Nimo and all the others will have to leave behind. The exploitation will have to be done by people who have studied classics, who can, you know, search, and take the good ones, and advance on them, and make them global and totally economic. But they are not doing that, and that’s what I am always worried about, music education in this country. I had also thought of maybe asking for foreign help, aid, to set up schools in Ghana that would teach jazz music. Jazz music has become fundamentally the total of all the world music. It’s jazz now. I was talking to the producer of um…this guy, this guy from Ethiopia.

B.E.: Mulatu Astatke?

E.T.: Mulatu, yeah. He produced my album, you know, for Strut. So I told him, there’s no music education in my country, so what are they going to do if I’m gone? All the kids we saw at the music school there, don’t talk about jazz. They don’t know anything about Freddie Hubbard or Coltrane, or anything about all these standard tunes. That’s the basis of our development. [Ebo mentions a trained jazz musician we ran into at the university who told us he doesn't get called for a lot of gigs because people think him overqualified.] You get stranded if you learn more than you are supposed to. They want you to go into traditional music before you get your recognition. But that’s not it! It’s the limitation that this particular aesthetics impose on you, I think, if you want to be a good musician, a well-known musician. Look at salsa today—they have good, well-trained musicians, who have played in America.

B.E.: Salsa, okay.

E.T.: Yes, salsa, Latin music. It’s very popular because the texture of the music in it is more advanced than what we have locally. So we could have exploited the funk even further than that if we had had well-trained musicians in jazz.

B.E.: Let’s come to the funk now. When was the first time you heard the music we call funk?

E.T.: Yeah, Ghanaians started talking about ‘funky funky, feel real funky’ during the James Brown era. They like the beat, and they like the bass line, and they like the tenor guitar line SINGS. It sounds like something from the north of Ghana. It’s steady and it keeps you going. And then the beat. They liked it straightaway.

B.E.: So what year is that that James Brown and funk hits here in Ghana?

E.T.: Let’s say in the ‘70s, the early part of the ‘70s.

B.E.: So it’s some time after you’ve returned. So you've come back in '66 and you’re doing these arrangements for highlife. Talk to us about how highlife and funk came together.

E.T.: Yeah, I think the highlife started fading out of people’s mind when the funk actually emerged. Because the funk had a similar rhythm like the highlife, it could turn even the average illiterate in the street on. People were singing James Brown songs, without knowing the meaning. I remember the funny things people would say in Salt Pond. Like James Brown sings, “I might not now know the day." And people started singing, “Ah me na too na day.” They don’t understand it, but they like the sound of it. And they like the dance that accompanies the music. So the highlife started actually fading out of people’s mind because of its major-key content. And the blues that came with the James Brown stuff'.

People liked the James Brown stuff because it was closer to the rhythmic propulsion of the highlife. And it was very energetic, and it was in the blues, you know. They like the singing style, you know, especially when he shouts—“EHHH”--everybody gets excited. There were no such gimmicks in the highlife. It was like taking the Westminster sound from the Church to the market and splitting it among the women. So funk was more preferable than the actual highlife. James Brown became popular because of the rhythmic content of his music, the tenor guitar, and the freshness of the horn sections--it was a mixture of exciting moments in music.

Shaibu, Dagomba goje player/singer (Eyre 2013)

B.E.: Okay, Ebo, you’ve mentioned a number of times that James Brown and other African American singers reminded you of music from North Africa, even the north of Ghana. And you had Aaron Sukura at the university put together this ensemble to play Dagomba music for us, from the north of Ghana. Let's listen to a little bit of what we recorded there, and get some reaction to that. [We listen to a recording of goje violin and vocal, gyil xylophone and percussion.] What do you hear in this?

E.T.: I hear a lot of blues in this music. This piece of music is certainly from the north of Ghana. I think it's the music of the whole belt of the tropics. It's all over from east to west Africa, the same type of music. When you go to North Africa, you will hear a similar type of music from Tunisia, Morocco... Only the language changes. Here, we hear a lot of blues. The fundamental key signature is a minor mode. It expresses the wailings the singer. He is wailing, he's not just singing, but he's lamenting. You see the depth of the blues in his song. So it is not that different from the blues we hear from America. It's just that it's being expressed by horns and piano. But in this fundamental aspect here, it is the wailing of a group of musicians. He demands sympathy. So it enables me to say that really the blues is from Africa.

M.L.: There were slaves that were taken from here. But there were also slaves here. Right? The elite had slaves.

E.T.: Yes.

M.L.: So, in the North, does some of this sound come from the people who are actually slaves here?

E.T.: No, no. We are not talking about slavery here. We are talking about the weather, food shortages, the suffering of the people of the North. The Sahara. The desert. Food doesn't grow. There is very little rain, and too much sunshine. That's why most of them found their way to the South. When you go to Salt Pond, there are communities to play this kind of music. The Dabanis are there. The Dagomba are there. The Fulani are there. They all came from the North to seek greener pastures. Life in the North is not like life here. Most of them are even still walking naked. Because of the weather, and because of lack of education.

It was Kwame Nkrumah who had forced them to go to school because he gave them free education. People from the North didn't pay any fees to go to school, not like the South, where we paid fees to go to school. That enabled them to shed some of these feathers away. Like today, we have a president from the North, who is well schooled. But previously, the northern kids did not go to school. They didn't even see the need for it. There was just the suffering part. There's no rain fall. There is always the desert, where very little food crops grow. And the sunshine is so abundant it's burning their houses. They're not developed. It is only recently that the development in the North. So that's what is the basis of their blues. It does not emerge from slavery. It comes from the hard life they are facing.

B.E.: Hard life up there, and highlife down here, right?

E.T.: [LAUGHS] Hard life there, and highlife here!

B.E.: Now, you said every Ghanaian knows this northern music. So you probably heard this music before you heard the blues and other American music.

E.T.: Yes, yes, yes.

B.E.: So try to remember what it was like when you first heard American music and right away recognized African things in it.

E.T.: Yeah, well, immediately it strikes you that this music... That's why they call it the blues. It's not just simply music for the comforted. It's telling me the story of the man who is singing it. He is not happy. There is no happiness living in the North. And when the Americans play the blues, you see the sorrow in their lives. It permits them to sing the blues, and it's always in a minor mode. You see? Whilst in that mode, it's a 12-bar rhythm change, but it's in a major key. When you think of the blues itself, it's in a minor mode. And its similarity cannot be challenged. It's true.

B.E.: What about the singing, the character of the singing?

E.T.: Yeah, it's wailing. It's not actually singing. The guy is like [GROWLS!]. You know, you go from the low octave to the high octave. It's blues. Something that makes him sad. It's not like, [SINGS] "God save our gracious King." No. It's like the guy is lamenting. And that's why the Americans even called the blues. It's a common saying, oh man, stop the blues, man. don't tell me your blues, man. It's the suffering of the American Negro.

B.E.: Let's talk about one specific American artist who always comes up in these comparisons with music of the North. And this is someone who I know has been very important to you, to Ambolley and really everyone of your generation of Ghanaian musicians. And that's James Brown. I'd love to hear you talk about any aspect of James Brown's music in terms of things you recognized it. And again, if you can, try to take yourself back to that first time you heard it and tell us what you heard in.

E.T.: Yeah, I heard it, certainly. It's blues. When James Brown started to sing, it's

not like Bob Marley who put it in a nice form of music. But this is hard music, blues, coming from a man who's been suffering. He's telling about the suffering of the American, excuse me, the black man. And so, you can see, you can hear that the guy is not only singing, but he's wailing. To wail is not to sing. He's telling you about his blues, something that is deep within him that is worrying him. And it's very disturbing if you go to the North. I bet you if you go to the North you won't feel as comfortable as you are here. Here you have AC, but North is so hot that you will want to stay outside. And then food is scarce. There are no medical facilities up there. So that's why they all run down to the coast. The Fantes have the see in the sea breeze. They have fish. We have two seasons of rainfall. But there, it's almost at the desert.

So immediately we heard James Brown's sing, you see that the man is singing a music of depression. There is no happiness in his song. Sometimes he goes up and says [CHOKED CRY], in the deep down of his heart. You know, it is natural for the northern is to sing that way. It is an expression of his blues.

M.L.: When we first talked about James Brown a few years ago, you talked about his drums. You could hear that the drums were a reduction of more complicated drum rhythms. You're talking about the blues part. But what about the funk part?

E.T.: That's why I want you to hear the rhythms from the coast. That’s why I want you to come to Salt Pond and hear the Bonze Konkoma. The rhythm on the coast takes your mind to highlife and its associated forms of music. And if I hear that in the funk music SINGS RHYTHM, and straightaway you think of adenkum, adowa, konkoma, the music before highlife. So if you hear early music coming from the coast, or even in Accra, where they have their kpanlogo. And in the eastern part of Ghana, we have the... when you call that? It's not kolomashi. It's kolomashi in Accra. But apetamba and adowa in the Fante region. In the Eastern region, they have... Well, I will try to remember.

So the melodic structures actually come from the North. But the rhythm that imparts the dancing comes from the coast. Because then you feel you want to dance. You want to support the music by gestures. And that's from the coast.

Konkoma musicians in Salt Pond (Eyre 2013)

Konkoma musicians in Salt Pond (Eyre 2013)

B.E.: Tell me if this makes sense as a way of thinking about all this. In the case of Ghana and highlife, you have the coming together of melodies from the North and rhythms from the coast and foreign sounds mixing int to make something new. At a certain point, that new music really makes sense. It becomes a finished thing: highlife. Now in America, you have a different process. You have the violent system of slavery. People from many backgrounds get thrown together, sometimes in a situation where music is not allowed. But in the process, a similar thing happens with music. Different African and European elements get put together and you end up with James Brown: funk. So there's a parallel. Does that make sense?

E.T.: Yes, of course it does. In America, this process has been developed into a dancing form. People want to express with gestures. Physical gestures in response to the music. Instead of just sitting down and listening to it and cry or laments to it they want physical expression. And that physical expression is from the Akan and the Fante music. It's the fusion of both. Now, people listen to this type of music, they sit down, and you see that there's no rhythm. There's no rhythmic propulsion that will make you dance.

B.E.: You mean the music we were just listening to from the North?

E.T.: Yes, just now. You can't appreciate this kind of music and dance to it. But when you hear the music from the South, it's also in the same minor mode. Because a story is being told about the Ashanti wars where the Fante lost about 1000 people. And it was a fierce war to remember. There is no jubilation. But their music is not as cold as in the North, where you have fundamental misfortunes like less rainfall, the heat, and lack of education and development. You know, here, they have seen development. And nature is kind to them. So their music, their type of music shakes. You know? It's vigorous.

B.E.: You say there is no joy in the music of the north. But in a way, aren't all these musical expressions a way of taking misfortune, sadness, defeat, and turning it into a kind of affirmation, or resistance? Maybe joy is too strong. But in the end, people are dancing to James Brown. They're dancing to highlife. They ultimately produce happiness.

E.T.: Yeah, that is the human thing, the ultimate physical appreciation of the music. So he wants to flex his arms up and down and dance to it. So there must be a form of rhythmic propulsion that makes you feel that way. And that is the fusion that goes with this kind of music from the South.

B.E.: Let's listen to a James Brown song. [We hear “There Was a Time,” and Ebo responds physically, clearly energized by a sound he says he hasn’t heard in a long time.]

E.T.: You see, the dancing emerges immediately. You know? But it still has the blues from the North in it, the way he sings it. What has he got? When I hear that song, it is like the guy is telling you he's got something. What is it? Some happiness? Or a discovery or realization? It's not like the music that we heard here [the Dagomba music from the north.] But the similarity is in the quality of lamentation, the blues in his sound. He's got something. What has he got? Now I've got it.

It is the blues that is immersed in a strong rhythmic propulsion. So that's what makes the music we call funk. It's the ultimate, something that inspires him to shake his body in all directions. To dance to it.

That's what is lacking in the northern music. It doesn't have a precise form of rhythmic presentation. So when you come deep down south, you want to dance, because people are happy. They fish and they have food. The sun is not tormenting them. So there is some kind of vibration that emerges from their music. You hear the timpanis, the fontomfroms. They express rhythmic propulsion that makes everybody wake up. But it's still the same blues.

M.L.: To make highlife, you need the blues of the North and the happiness of the South.

E.T.: Yes. But also, highlife itself was highly influenced by the music of the church, from the Westminster, and the music of America. Those melodic structures strengthened the highlife. And it was almost always in a major key. Except syki highlife, which was influenced by the adowa music from the south, in a minor mode. Could you play that song again?

[We listen again to "There Was a Time."]

E.T.: What made him say “Hah!”? There was something he could add to the music, not with words, but emotionally, “Uh, ah!” That sounds more like…There is something in the north, something that is killing them, and it’s not slavery and colonialism, it’s nature.

M.L.: When you say north, let’s say someone from Nigeria was sitting here, would he also say that’s from the North of Nigeria?

E.T.: Yes! Of course.

M.L.: So, if you could do a little diagnosis, we are trying to understand what is it that changes from funk to Afro-funk? What is it that you would have done differently if you were covering this song?

E.T.: I’ll tell you frankly, we would like to play it exactly the way it was, because it’s real funk, and it gives you the impact to dance, and you see the similarity the way he voices out, like a northerner, similar to “There was a TIME,” He put more emphasis on what he want to say, and rhythmically, and you feel him not like a Sinatra or Elvis Presley, you really see that this is a black man interpreting a form of music.

M.L.: So what’s the difference? So why is Afro-funk not just James Brown copies? You didn’t start writing songs just like this. You took it to a different level.

E.T.: You would like to do it like James Brown, sing it with the same impact, with the same feeling. You see what I mean? And everybody who listens to this will turn around and dance, even today. I wish we could have James Brown today, instead of having the reggae stuff. This is more original African, than the reggae, like an English foxtrot. I would prefer music closer to James Brown, because you can hear the African. I would prefer a James Brown Day, a celebration, than a Bob Marley thing. The Bob Marley thing is like, you have the colonialism, you have slavery. But with James Brown, you have slavery, and it’s more intense. The guy wants to be liberated, through music, and he’s saying it.

With Bob Marley, it’s like criticizing. “Get up stand up.” It’s like the English foxtrot, it’s not as exciting like the American funk music. This is music that comes from a deeper form of blues than anything else. Not even Lord Kitchener could turn people on like that. He make them dance, but here you see the political reaction in terms of music. And the funk music is more intense than any form of music. Even more than the Afrobeat that we play now. Afrobeat is secondary to this. What I just heard, I haven’t heard in so many years. It was in the 60s, you know, but it still has that impact.

Aaron Sukura, Ebo, Sean, Banning

Sean Barlow: Did you ever meet James Brown?

E.T.: No. He was in Nigeria, but I never had a chance to see him. But I can tell you this. James Brown is as unusual an artist as has ever emerged in America. When he was in Nigeria, every Nigerian was mad…Every Nigerian was, ‘EHHH!!’ Like the real guy, the Jesus Christ, is here. And I’ve never forgotten how exciting that was. Even if he sings ‘If I rule the world’ even though it’s a ballad, but the way he sings, you see that it’s an African, there’s something burning in him. He treats it like he’s treating anti-slavery. And it takes you back to the north, and you see that it’s more original. So the similarity with James Brown and the people up there—you can feel the same thing. If James Brown was a politician up there, he would win all the elections.

B.E.: You convinced me, man.

M.L.: But when you say Afrobeat and Afro-funk are second order to the original funk, for many of us fans of Afrobeat of or Afro-funk, we wouldn’t say it’s better. You guys are doing something that even James Brown isn’t doing. That’s why we love this music.

E.T.: Yeah, but it’s James Brown at the center. I tell you, me and Fela, we will all agree to it. The drumming is quite different, the drummer’s taste, because we have more drums. You can add more drums to this. But the excitement in this kind of music can never be achieved in the Afrobeat.

B.E.: You were talking about the North, and that vocal, and the feeling of suffering, and the role of nature. But what is the role also, another thing that’s different about that belt, is most of those people are Muslims, they have Islam, and Islam has a great vocal tradition that’s very intense that way. What’s the role of Islam in the creation and the history of that way of singing?

E.T.: Islam is religion, but this is social, this is culture. Like I’m a Catholic. If I don’t go to church, I won’t sing the hymns. But Islam is like a form of religion in the north. It’s not their basic culture.

B.E.: So you think that way of singing and stuff like that goes way further back than Islam.

E.T.: Yeah, you can feel that this music coming from the northern part of you. You know, the people in the North. What makes James Brown say, “There was a DAY,” and then “uh!” What does that ‘Uh’ mean to you? How would you interpret the meaning of the ‘uh,’ the ‘oh’ and all the things that he does? There’s no answer to it, but you can see that it’s an inner feeling that needs to come out, not in music but in another emotional attitude or…I don’t know how to describe it.

M.L.: It’s interesting that Islam arrives in Northern Ghana and Nigeria somewhere in the 17th century, 1600s, so it’s right at the time that slavery is beginning. And music changes too. When you do that song where you’re talking about that semi-tone from the E minor to the F major 7th, that’s very much like some of the key modes, the Islamic Arabic modes that have that semi-tone right at the start, like hijaz or other modes. So, do you think that perhaps melodically, bringing that in helped shape the music of the north some, even though the feeling was much older?

E.T.: I still feel that the music of James Brown come from the North. He’s attitude, his emotion, his approach, and the kind of music is not just music, it’s something that is exploding. It’s the truth that this is what is happening here!

B.E.: But you also seem to be saying that what he is getting from the north is very old, even older than this Islamic influence, yes?

E.T.: Yeah. Because it’s natural. It’s an inborn thing, we’ve been living with it for years.

Geraldo Pino

B.E.: Okay, coming back to the emergence of Afro-funk in Ghana, I want to ask about a few things that happened in the late ‘60s an dearly ‘70s. First, there was this singer from Sierra Leone, Gerardo Pino, famous for channeling James Brown. Did Pino help to make people here feel like, "Okay I could do this."

E.T.: Of course, he made the Ghanaians feel that, because his band was of the same size like James Brown. They were using the keyboard, and they were using two guitars, rhythm and the lead, and then they had the vocal styles and they have equipment to boost the sound. It was quite a technical thing, the technical aspect of it. Not just the musical aspect of it. They had electronic equipment that gave the same feeling of, like the James Brown thing., So he became very popular. And he was playing James Brown’s songs.

B.E.: John Collins talks a lot about the importance of the Napoleon Club, Faisal Helwani’s club, where Fela used to play. Talk about nightclubs, and maybe that one in particular. Was this a place where the Afro-funk sound really started connecting with an audience?

E.T.: Yeah, the Napoleon club was modeled like any international American or English club, or a club on the continent. The décor was like in Europe. Whilst the other nightclubs were like, you sit outside, it’s not well decorated. But the Napoleon nightclub had lighting systems and good acoustic equipment that matched international standards. And they played that kind of music. And it was also an important place where African music was enhanced. You know, the Napolean featured the Hedzolleh Sounds and other groups, Basa-basa, and Eddie Kamfoh. These groups were playing African music and putting it into the same level with the music that come from the west, and from America.

B.E.: This was all part of the vision of Faisal Helwani. Tell us a little bit about him.

E.T.: Well, Faisal Helwani was enthusiastic about outdooring African music. And he was an entrepreneur who would support music and musical shows more than any one else in town. Faisal supported the musicians union; it was his money that actually set it up. And he supported individual ideas, and he even brought Fela, Hugh Masekela, and they were all common products in his nightclub.

B.E.: Faisal came from a Lebanese background in Ghana. And he wasn't the only one to become involved in Ghana's entertainment industry. But he was probably the most important, right?

E.T.: I think Faisal invested more in show business in Ghana than anybody ever did. He even set up a recording studio. He had about three groups that he catered for. I think that his input into the entertainment sector was magnified even by his own personality. People respected him for his color, and people also respected him for his money, and so people of that category, always supported his ideas. He was famous because he was an exciting person. He can do things in the entertainment, with all his money and strength. So I think he has some credits on his back.

B.E.: How about the Soul to Soul concert in 1971? Was that important to the development of funk in Ghana?

E.T.: I didn’t watch it, but I’m also sure that Ghanaians welcomed it. They want to repeat it now, I heard some weeks ago. Some lady was is the country, she even came to Salt Pond to see me. We spoke about it. But the Soul to Soul thing, if it will be done again, must involve the cultural musicians more than the enlightened musician.

B.E.: So when it happened in 1971, it was the first time that Ghanaian audiences had really seen soul and funk. They saw Wilson Pickett and a lot of great music that maybe they had heard on the radio or on records, but now they’re seeing it on stage. How was the audience and the scene in Accra here different before and after than concert, what did it change?

E.T.: I wouldn’t say it changed their mood or their respect for the music, it was just an experience to see the American musicians perform. But if you talk about Soul to Soul then we have to talk about roots to roots. The roots of these…the agbadza, the adenkum, the asafo, and the unknown territory that has not been exploited by music. What we are doing now is all cosmetic; SINGS. You just play classics to cover up our shortcomings, or the loopholes. But, if we were to play the root music, we would play that kind of music, that we have not been able to bring to the stage yet in this fundamental form, in this rudimental form. We always want to cover it with classics or jazz.

But if you talk about Soul to Soul, there should not be any cover-up. What we have here, years ago, must always be consistent with their expectations. The Americans were not expecting to hear an African play blues like I’m playing, they wanted someone with some wild jungle clothing and some jungle manners and musician who doesn’t look like you at all, and doesn’t even smile. He’s seriously playing his drums, because the drums are sacred instruments. Their music that they are playing in the chiefs house is sacred instruments, sacred music, it’s not music just for fun. It’s music for expression. When an old man gets up to dance, he’s expressing what the music is saying, and his reaction and attitude towards it…and when the chief gets up to dance, it is not just emotional, it is rather conveying the anticipation, the expectations of the audience. You don’t just get up and dance. There are modalities to dance that type of music.

[Keep an eye out for the second part of this interview, in which Ebo takes us to Salt Pond to hear konkoma music, and talks about Sinatra, Nkrumah, hip hop and hiplife. Thanks to Morgan Greenstreet for transcription help with this interview.]

Ebo and his wife in Salt Pond (Eyre 2013)