African art historian Lubangi Muniania has lived the life of modern Congolese music. Growing up in Kinshasa, he experienced it up close and personal. And with his New York-based production company, Tabilulu Productions, he has worked with the greats as they performed, toured and recorded in the United States. He’s been a commentator on a number of Afropop Worldwide programs, always providing fascinating context and detail. For our 2022 program, “Remembering Papa Wemba,” Afropop’s Banning Eyre spoke with Lubangi for insights about this most consequential Congolese singer and bandleader, and as ever, Lubangi did not disappoint.

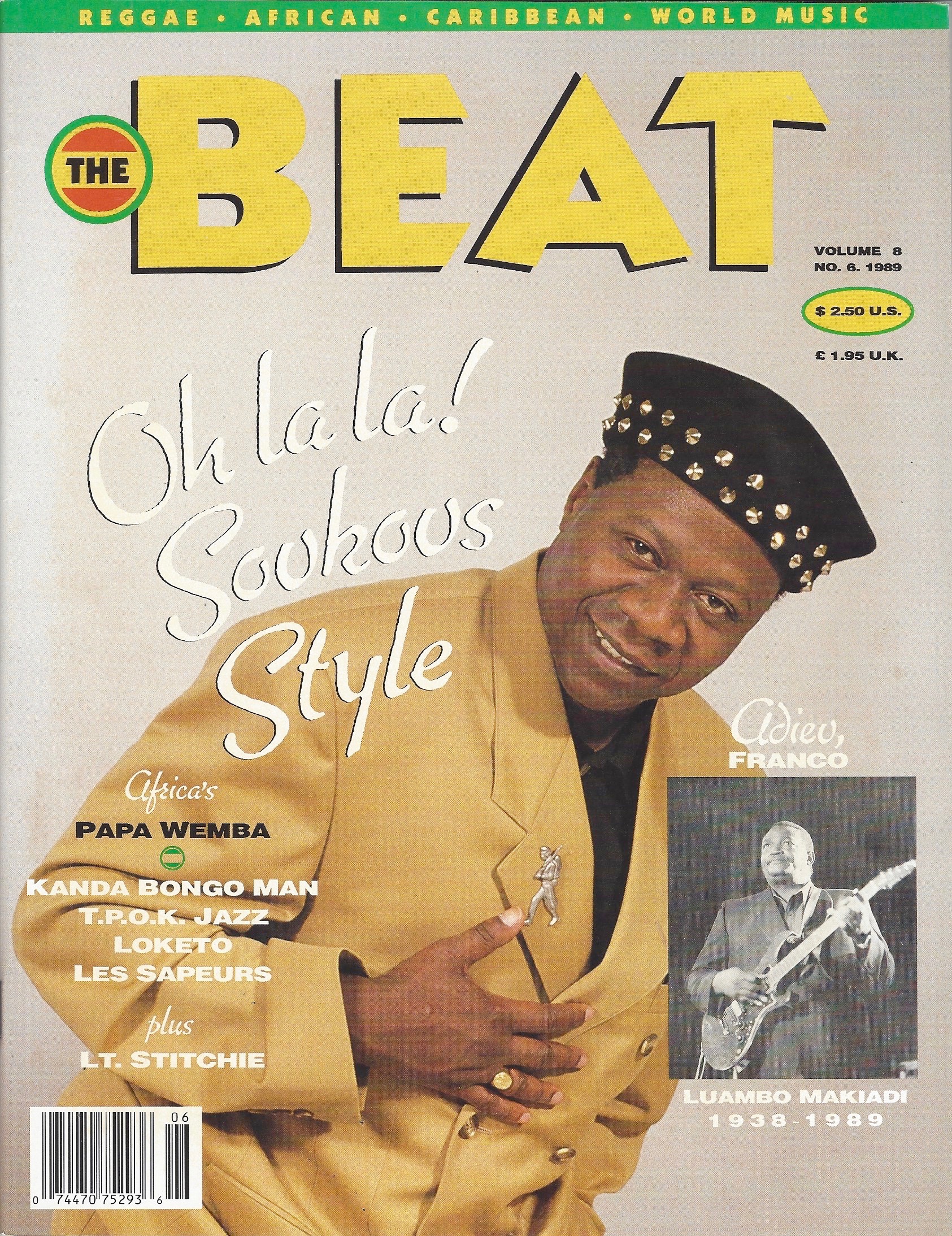

Their conversation began with a focus on a concert Afropop recorded in Kinshasa in December, 1987, the 18th reunion of Zaïko Langa Langa. They had played the night before in the Chinese-built Palais du Peuple. Now they were in the open air on the Kinshasa esplanade, with a crowd of thousands in attendance. This transcript also includes occasional excerpts from our interviews with Papa Wemba over the years.

Banning Eyre: What can you tell us about that 1987 concert?

Lubangi Muniania: It was not just a regular concert. It was a reunion, so some of the original members were there. I recall Mbuta Machakado came out to the podium and he did sing two songs, and he interacted with the crowd, and Papa Wemba was also part of the reunion. [He had left Zaïko in 1974 to start his solo career.] And of course he did sing quite a few old songs. Bozi Boziana, also from the original Zaïko, was there.

Papa Wemba’s interaction with the crowd was quite interesting. He was very comical. He improvised his role as MC in a way. So he was asking, “Who remembers the title of this song?” And of course some people remembered. Then he said, “But who remembers the author of this song.” And then he would say, ”If you get it right, I'll pay you 5,000 Zaires.” And then Mbuta Machakado came on the podium, and Papa Wemba made a joke about “Why wasn’t Mbuta Machakado with us yesterday? He should tell you why.” Because it was probably about the money. He wanted Machakado to tell people why they didn’t pay him. So Papa Wemba put him on the spot and then the crowd liked that.

That's wonderful. You know, we recorded both of those concerts. It’s funny. Back then, we were not allowed to take pictures in public places, but some how it was no problem to record these historic concerts.

I wouldn't be surprised if you're the only ones who have those.

Listening back after all these years, I was surprised at how good the sound is. This was just microphones held up in the air. The singing is really particularly beautiful. But let’s go back to the beginning. If you were describing Papa Wemba to someone who didn't know anything about him, What would you say?

Papa Wemba was an unusual person. Later on, people were surprised to see that he was bigger than the music, in whatever he did. For you to understand that, you have to understand where he came from, and the way he grew up. His father was in the military, and though his mother was a housewife, she was involved in traditional things, like the traditional christening of children. It was the most important part of someone’s coming of age. The modern setting was not really there for that, especially before independence. Tradition helped children and newborns, giving them the energy to become active members of society. The traditional setting, or settings—I'll put it in plural—were there for that. Those who kept those traditions were mothers. They were housewives during the day, but at night they were traditional leaders. So Papa Wemba grew up in that type of household in the community.

Papa Wemba: My mother was a crier. In our culture when there is a death, the body is kept outside for two nights. People come to cry and sing. My mother sang for the dead, and everywhere she went, she would take me. So I grew up with this melancholy singing. I am also a Catholic, and I sang in church. In that music, there are also a lot of minor keys. It's like rhythm and blues: the heart is speaking.

A little bit after that, Papa Wemba took on a very, very important role that most people don't know about: he became sort of a community leader. Today we would probably say “organizer.” In the community, he was in charge of orientation for so many youths. Soccer was part of it. Papa Wemba was a leader where he grew up in Kinshasa.

Which part of Kinshasa?

Matonge. During the Belgian time, it was known as Quartier Rankin. Papa Wemba and all the original members of Zaïko Langa Langa were there. That was where most of the workers lived, the people who worked for the colonial power as helpers or whatever. Papa Wemba came out of that kind of household and community. He became a coach for a soccer team in his neighborhood. He already had this leadership quality; he knew how to pick his teammates and players, and how to help them develop and become active in the community. That alone gives you an idea of what shaped Papa Wemba’s personality as a leader.

That's very interesting. And this is before he's a singer.

Yes, when he was still a kid.

Papa Wemba: For 10 years, I was alone with my mother. She was 11 when she had me. But she was too small, so she didn't have any more kids for 10 years. My father fought in the Belgian Force Publique from 1939 to '45. In the family, we lived as if we were in the village. We spoke only our regional language, Tetela. So I grew up as if I was in a village, but I was in a modern city.

Lubangi: You are a child but yet responsible already at the age of six. It was not just go out and play. No. You had to be there helping your mother. So you learn so much, and quickly. By the time you become ten years old, you already know what means what, who means what, what needs to be done. By the time Papa Wemba became a teenager, he already knew how to organize his space, his house, his community.

Those qualities came through in his singing, his choice of songs. Papa Wemba did not have a problem transitioning from Lingala to his native language, Tetela. He knew how to weave them together. The chorus would be in Tetela and the rest in Lingala. He was doing it naturally. I would say he was a leader in that type of style.

And he did that even back in Zaïko Langa Langa?

You have to understand one thing about Papa Wemba. Among his many qualities was timing. Zaïko was a little bit different than when he became a solo artist. Zaïko was a bunch of egos together, a bunch of friends, so each one of them wanted to showcase his talent, his ego. Papa Wemba knew how to play with that, when switch it on and went to switch it off. The people with the biggest egos were those who were born in Kinshasa. They were already 10 steps ahead of the ones who came as kids to Kinshasa.

So you had all these the egos. I'll give you the example of Evoloko. His ego was through the roof. Then you had Gina Wagina and Nyoka Longo. Then you had Mavuela. He was taller than any of them, bigger in life. So all of them were Zaïko. It was crazy. How do you excel when you are among all these people? Papa Wemba couldn’t show everything that we would see when he became a solo artist. But you would see bits and pieces in Zaïko when he was there.

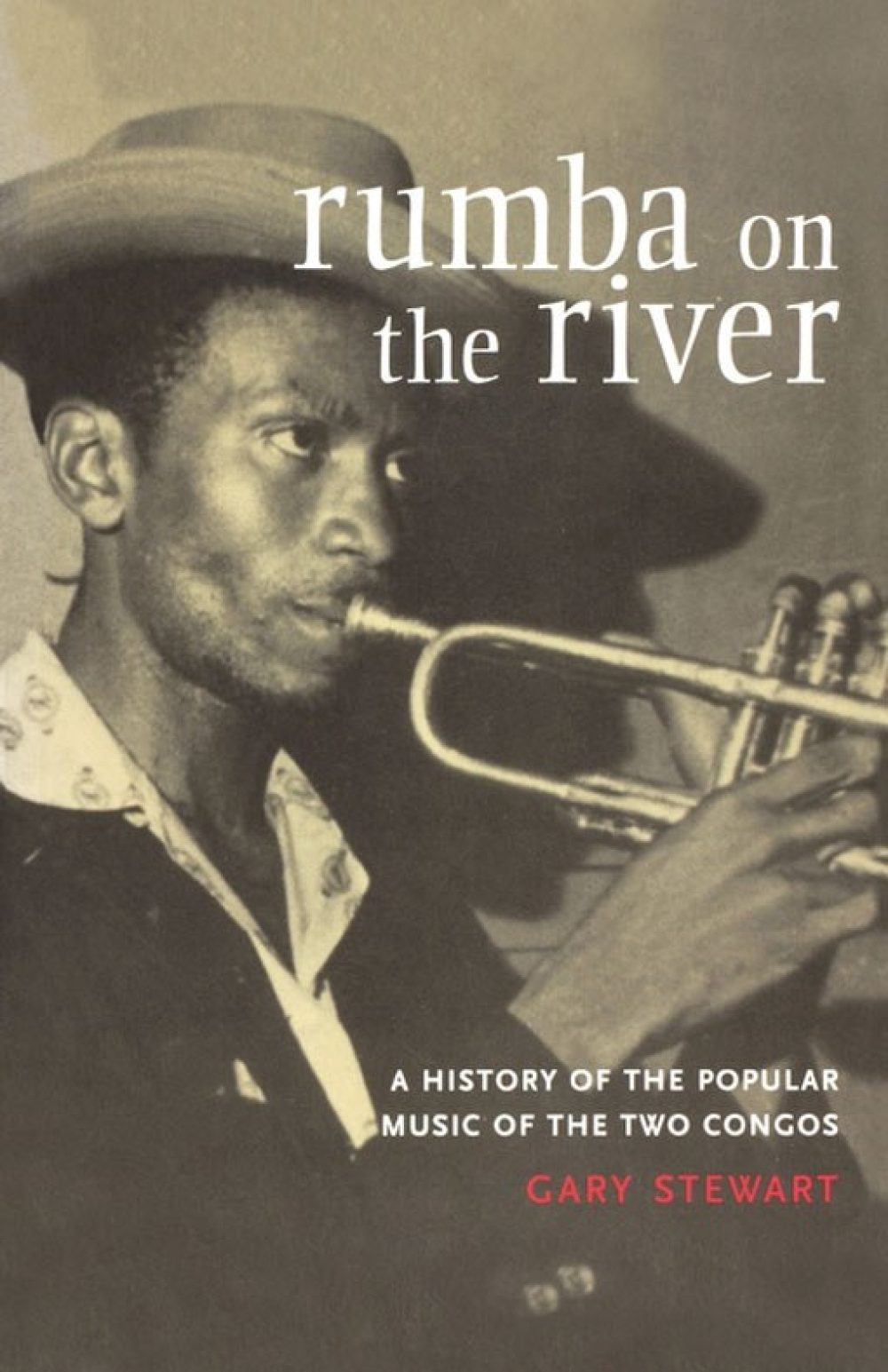

I'd like to hear more about the early days of Zaïko. I read in Gary Stewart's essential book, Rumba on the River, where a reviewer described Zaïko’s vocal arrangements as “bizarre” and “discordant.” Obviously, some in the older generation didn't get it. But Zaïko became enormous. Talk about that moment when they first arrived on the scene.

Zaïko started from school students in Matonge. They were in high school, pretty much all of them. There was a group before called Beguide. That group became the original Zaïko.

Wemba says that he and guitarist Manuaku Waku were the original members.

Papa Wemba: Zaïko was created in 1969. I was among its founders. Manuaku Waku and me. The others came later. At the time, there were not many young groups in Kinshasa. There was Thu Zaina, there was Simba, and there was Zaïko Langa Langa. It was unbelievable. It was like the Beatles in London. In every concert, Zaïko was attracting an incredible world, an insane world!

Lubangi: There's a debate about who came first. Because the fact of your being there does not mean that you started the group. Nyoka Longo was part of Beguide which later on became Zaïko. There was already a group of members, so he would tell a different story.

Papa Wemba: When we started with Zaïko Lango Lango, it was the era of rhythm and blues, with big singers like James Brown, Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Sam Cooke... My favorite was Otis Redding. And then in France it was the time of singers like Johnny Hallyday and Claude Francois. We Zairian musicians tried to embrace it all, without forgetting that Congolese music began with Afro-Cuban rhythm.

Zaire Ya Bakoko, “Zaire of our ancestors.” Langa Langa is a flower that floats in the river. I was the one who gave this name, Langa Langa. That was me.

Lubangi: Langa Langa, the word, is Papa Wemba’s contribution. It's a medicinal plant. You see again his traditional background with his mother coming through.

That's interesting. Gary Stewart’s book he says that “langa langa” means “to get drunk.”

I don't know about that. But maybe there's some strange connection. But keep in mind, this was way before the name of the country changed. The country changed its name in 1971. Zaïko was already there. Zaïko was not a name that Mobutu came up with.

So it wasn't a response to Mobutu’s authenticité initiative.

No. Actually, Zaire was a name that the Portuguese mispronounced instead of saying nzadi, which means “river.” So they started calling that river “Zaire.” That's why it was easy for Mobutu’s government to say, “Let's come up with a name that is somewhat neutral, that will include everybody. Because the river crossed the whole country. If we call it an nzadi we will be locked into one region where the Bakongo are. The name of the river keeps changing as you go inland. So they decided to come out with this somewhat neutral name, Zaire.

So it's using the idea of the river to unite all these different ethnic groups.

Yes, and it was the name of the currency first, before the country. The currency was called the Zaire.

So coming back to the musical impact of the band. Once Zaïko hit the scene, it was a different sound than what people had known with Franco and Kabasele and Dr. Nico. There were no horns. There was more complex vocal and guitar arranging, and lots of animation.

Well, Zaïko as a rebellious band. They did not follow the rules of the game in the music that was there before then. They rebelled against the rules. The rules said, “If you wanna be considered modern, you gotta sing like us. Do it like us. That's the school.” And then you have these kids who did not want to have saxophones, just their voices. And they were dancing to their own music with moves that would just make the adults angry.

Wemba says that before they formed there were very few young bands. There was a vacuum.

Right. There was a vacuum that had to be filled. So whatever they did, it became the expression of the group. The Congolese are now living in the cities. They are independent. Their parents are working in the government. There are some good salaries now so what do kids do? They wanted to express themselves. But what made them stand out was that they befriended most of the children of the rich and the authorities. And those children became their sponsors, helping with whatever they wanted to do, whether it was footing the bills or creating parties.

The children of the elite supported them.

Exactly. The new elite. They were radically independent. Now, the elite themselves were hanging out with Franco and Kabasele. But their children created their own space.

Papa Wemba: In a group where there are a lot of stars, there's always a Cold War. We spent four years in Zaïko, and then we quit, Evoloko, Mavuela, Bozi and me, to create the group Isifi Lokole. Isifi lasted only one year because we were all stars. We abandoned Evoloko and made another group Yoka Lokole. Now Yoko Lokole, it was again the same problem. So I slammed the door. I told myself, “Now, no more. I’m going on my own road.” That's when I created my own group, Viva la Musica.

Let's jump ahead to Viva la Musica. Of all the bands that split off from Zaïko. This was the most successful and for many people the best. Do you agree with that?

Lubangi: I agree. There was a guy called David Mwanda. He was the very first percussionist of Zaïko. I don't think he was a great percussionist. But he needed to be there. He needed to be in the band and make sure the band could grow its own legs and go. David was a community organizer. I believe he was older than Papa. I would say that he was the one who actually founded the Zaïko. He knew how to pick people. He picked the best. So someone like him, being part of a Zaïko, set the tone for what the band was going to become. He picked someone like Nyoka Longo, who was actually studying to become a priest. So he was already a very serious and well organized person.

Another person was the rhythm guitarist Enoch Zamwangana. He was actually a captain of that soccer team, a well-organized guy, very disciplined. So behind all these singers, they allowed for the stars to do whatever they needed to do to attract their clientele. Evoloko, Gino. Mbutu Machakada... David and Enoch let them do whatever, but when it came down to business, there was a team that held it together. And that's what made them last longer, until today I would say.

What about Viva la Musica? Papa Wemba had had these two other short-lived bands, but this one worked.

Viva la Musica was very much a product of the team Papa Wemba put together. When Isifi did not work, it was because they couldn't work together. Too many egos. Papa Wemba was actually kicked out. “You're too much. Get out of here. This guy when he was with Zaïko, he seemed to be so together. What’s going on?” So they did Yoka Lokole. Same thing.

They were trying to bring forth a mixture of traditional and contemporary music. Papa Wemba was trying to bring something new. It didn't really work because of the egos. Papa Wemba was also out of that band. But now, he had a following.

Remember in his background, he was the one who used to organize people in his community so they came together. They were people who knew and believed in his ability to do something greater. Papa Wemba was listening. That's how Viva la Musica became something. He listened to his girlfriend at the time, Sharufa. She’s still alive. He sang a lot about her. Sharufa was a young business-woman who was traveling a lot. And he listened to her. Now, he was able to listen. And this time he said to his musicians, “O.K., tell me what you want to see happen." That's how Viva la Musica became something.

Papa Wemba: I played at the Zaire ‘74 festival with Zaïko Langa Langa. It was full, full, full of singers from all over the world: James Brown, B.B. King, Johnny Pacheco. I had seen James Brown. I had seen B.B. King. The discovery for me was Pacheco. That’s where I got the name Viva La Musica. It was Johnny Pacheco. At the end of each song he would shout, “Viva La Musica! Viva La Musica!” That's when I got the idea of creating a group that must be called Viva La Musica.

So this time, Papa Wemba was in charge. He didn’t have to deal with other egos.

He did not. But he had loyal helpers, like Sacre Zaza. To this day, if you want Viva la Musica, you still have to go through Sacre Zaza. He was the original. He was never able to leave Papa Wemba. He was there to help Papa Wemba recruit, but he made sure that Papa Wemba was the leader, in charge. Nobody else but him.

Now, Sharufa, the girlfriend, was traveling a lot and she went to Nigeria. It was the ‘70s and she went to the Kalakuta Republic. She saw how Felt was running Kalakuta. She said, "Papa Wemba, I saw this fellow who is in charge of his own thing. He created this republic that he called Kalakuta. I think you should create something. A village.” So that's how Papa Wemba is able to create Village Molokai. They were looking for a name. He picked this name out of Hawaii, one of the islands, Molokai. He didn't want to go with the real name of any village, because if you claim to be the chief of that village, you probably have some serious problems with the real chief.

He had to make something up. It's kind of like Zaire.

Yes. It gave people the ability to think and create themselves. And it was a movement. People wanted to re-create themselves with names, with companies, with bands. It was a great moment to live in Zaire to see how these people who were denied freedom were recreating themselves. That's what Africa was! People recreating themselves, creating kingdoms. Nobody told them what to do until the Europeans came in shut everything off. They couldn't re-create themselves, even their own names. Everything was denied. So with Zaire, Mobutu, said, "Hey, I'm the new president. I am Mobutu. It means such and such and such. Let's re-create ourselves.” That's what authenticité was about. People went back to try to find out the meaning of their names. If they didn't have one, they created a new one. And it was not just names; it was everything people were doing. That’s when Papa Wemba was bringing in the lokole, the log drum. That was one of his responses to this new call.

Papa Wemba: There was not really a complicity between Mobutu's politics and traditional music. But Mobutu did contribute enormously to that trend when he proclaimed the return to authenticity. All the musicians started singing in their maternal languages. And I was the first musician to incorporate a traditional instrument in modern Zairian music. I introduced the lokolé. This drum was used for communication between villages, like a wireless telephone.

Now let's connect that with what comes around the same time the emergence of the “sapeur” movement, the high-fashion look Wemba became known for.

Papa Wemba: When I created my group Viva La Musica, I said I have to get beyond the ordinary. If you look at rock bands, what distinguished them was often their accoutrements. So I said, “O.K. I need to tap into something that the others have never done.” It was a rebellion. So I started wearing clothes from the great fashion designers of France and Japan and Italy.

Lubangi: The sapeur movement is a bit complex. A lot of people don't know how to explain it. Sape is an acronym that was well known— Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes (literally "Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People")—but the state of mind came way before the acronym. It's always been part of the tradition to have clothing, intricate clothing. Even if you look at traditional outfits, you will see the chief always had all this kind of look. Part of the tradition was that if somebody died back then, the only possession you were buried with was clothing. So clothing was a big deal.

When colonialism came and had its foot down on everyone, what replaced clothing were these fantastic military or high officers with epaulets and medal. Oh wow! So the chiefs started wearing those, and they became very impressive. Then some people were not chiefs, but were with the colonials, would wear suits, and when they would go to places where people didn’t have suits, they appeared to be special. That's the state of mind.

That state of mind did not change. It just evolved from the traditional to the modern. When Zaïko was Zaïko, they were performing, and some of them would wear a certain fashion. They would say, “I'm wearing this just to let you know that I'm special.” It was just a regular shirt and jacket, but that was part of it. So for Papa Wemba with Isifi and Yoko Lokole, those elements were already there.

Now, when Viva la Musica came, the very first day they performed it was on TV, and we see Papa Wemba wearing this hat and a velvet suit, shiny shoes. They asked him about it. He talking about it, and he give it a name: Muniere. Oh my goodness, then it was everywhere. That is a time when Mobutu had outlawed European suits. They outlawed neckties. So Papa Wemba, somehow he came with this jacket, but he would not wear a tie. He stayed right on the border of the law, so they didn't say anything. “Well, he's not wearing a tie. It's O.K. He can run with it.”

But nobody talked about “sapeur” then. Now the interesting thing is, if you cross the river to Congo Brazzaville, they did not have this. So they were wearing suits the European way. Over there, they also have the same state of mind of clothing. So when they expressed themselves it was through European suits, 100 percent. Now, in Kinshasa, you had to be creative. You had to play with colors because you didn't want to wear European suits. Papa Wemba was very famous in Congo Brazzaville, so whenever he went over there, all these people with wearing suits would come to him and greet him. He embraced them, but differently. He had to play with colors. So that's how the whole thing was born. When he went to Europe, he found out that the Zairian and the Congolese were called “Zai-Co,” Zaireans and Congolese. But it was the same mindset.

Papa Wemba was in the same spirit, and that's when he found out that the society of elegant people in ambienceurs existed, because whenever they went to parties, they showcased what they were wearing to underline that most of them went to Europe thinking, “O.K. I'm gonna go there and it's gonna be great. I'll become a doctor and I'll go home.” So going home, it became difficult, because most of them did not become doctors. So they decided, "I don't need a degree to make a name for myself.” So what they did was they stuck with Papa Wemba to make a name, because Papa Wemba was very popular. He would make music for them and sing for them, and they would come in and instead of showing their degrees, they would say, "Hey look. I have this outfit.”

Georgio Amani.

Exactly “Just go in and find out how much it costs and you will know my value.” So it was like, you wear something that is out of reach, your value goes up. And Papa Wemba was like this referee. He was saying, “So-and-so is wearing these out of this world shoes made by Georgio Amani.” And the other one would say, “Oh, no. Mine is Yohji Yamamoto.” “Oh wow.” “It's Japanese.” “Oh really?” So it became this interesting dynamic, where people were focused on becoming elegant. “Hey, I'm in Europe. I'm just gonna drink, have fun and dress well.” “But where do you get the money?” “Don't worry about it. Just watch me on stage.”

So musicians started playing with this. They became actors in a way. It was a role you were playing every weekend. And the fans work hard during the week, but on weekends, they were no longer who they were during the week. So it became this fantasy of people. And the soundtrack of that movement was Viva la Musica.

Papa Wemba: I've seen singers like Alpha Blondy, Youssou N'Dour, Mory Kante, Salif Keita who are almost like me. But they have understood that you have to go to Europe, to leave Africa, in order to promote your music throughout the world. I have slammed the door on the music I made in Zaire. I abandoned my musicians who came with me to Europe. I am now playing with professional musicians who live in Paris.

Let's talk about the the time when Papa Wemba moves to Europe. Viva la Music is starting to get a little bit shaky because Wemba spending time away doing other projects, like his gig with Tabu Ley Rochereau. This is around the time he starred in that film La Vie Est Belle. It was first shown in Kinshasa in 1987. So it’s another new project. And now he goes and makes his own band in Paris with professional musicians and he begins to forge this new identity. How does that go down in Kinshasa?

It didn't go well. Number one: what gave him this desire to go to Europe was Kanda Bongo Man. Kanda Bongo Man left Zaire a long time before. We didn't hear about him. And then suddenly Kanda Bongo Man is on TV in France, playing on big stages. He bought a house in France. And Papa Wemba was like, “Wait a minute. This guy was not near my success. So how can he do this in Europe?” But listen to what the music is doing. Kanda Bongo Man wasn't singing for people to hear him. Kanda was singing for people to dance. That's what made him a success. Papa Wemba’s success in Africa did not bring him money the way he wanted it to. People were broke, but they were there. So Papa Wemba said, “Wait a minute, I have to start making real money. I have children. What's my future life? I can't just be a success. I need to have money.” That's what Papa Wemba went after in Europe.

He decided to do this new kind of music and still be a local superstar. And of course the villagers of Molokai, his village, they were very angry. “Papa? What are you doing? You were doing music for us.” And he said, “No no no, I'll come back. I'll come back.” That's what put him out there, doing music for the world. And he went all out.

When we interviewed Papa Wemba in 1989, it sounded like he was leaving Congo music behind for good. But within a few years he went back to doing both. Is that because he was responding to that public back home?

Yes.

So then he's in this interesting position where he has two bands, and that's complicated. Did that help in terms of his reputation back home? Did they sort of say, “O.K., you can still do that as long as you keep doing music for us?”

He came back. He told people, “I want to do my thing.” But in reality, he felt like he was going down. His contract with Real World was supposed to be for one album a year. But Papa Wemba was not used to doing just one album a year. So he was there in France hanging around going to the studio. And people said, “Wait a minute. We can't just see you on the street. We need to see you on stage.” So that's when he said, “You know what?” I signed the contract as Papa Wemba. But this band Viva la Musica did not sign the contract. So he started playing with Viva la Musica, doing concerts every Saturday. He went back to Kinshasa. Then he created another band for the Kinshasa audience. And he became very busy. Very busy!

Yes that would keep you very busy. So all of this leads up to the problem he had with the French immigration authorities. What's the story of that?

What happened was in Zaire, the country was going down. The economy was being destroyed. It was being attacked from outside, from within. Of course people outside wouldn't know, but people inside knew there was a problem.

This is the late ’90s.

Yes. Things were really bad. Terrible. So when the new Kabila regime took over in 1997, Papa Wemba was not the choice of Kabila’s government. No one was allowed to come out of the country. Civil war broke out. But musicians such as Papa Wemba were allowed to go out with their groups, with like 25 members. 27. All of them would go out and perform in Europe, stay there for a long time and come back. That's when some people approached him and said, “They trust you. They don't trust us.”

Congo was dying. There was no future. And they asked him to help them with their children: "I'm already old enough. I can die here. But I want my child to have a chance to go to school to see something else because what's coming it's just going to be war, war, war. We know this." And that's when Papa Wemba became involved in helping his musicians first. He did help his musicians. When he traveled he told him, "There's nothing back there. You can stay here if you have the chance." In fact one of them is Julius Djanana. And of course his son became Maitre Gims, a huge star in France now. So thanks to Papa Wemba, a lot of musicians were involved in helping the youngsters to leave. Today some of them are doing well. They are pastors and lawyers, and Gims is huge.

Of course. But that got him in trouble.

It was illegal. When they allowed Papa Wemba to travel with his musicians, they did not allow him to bring non-musicians with him. But he used that status.

And that's what it came down to in the case. He had brought non-musicians posing as musicians.

Yes. Somebody said, “You know what? We think Papa Wemba is traveling with too many people. Thirty people? How many of them are musicians?” So when they checked, they realized that maybe 15 of them were not musicians. So his defense was, "They're my fans. I want them to come and see the concert." Of course they want to see the concert, but after the concert they never went back. Who would want to go back but they were raping women and killing people. It was just spreading. Who would want to go back? So that's why people stayed. Some people say that in Germany in the ’30s, it was the same way. Some were trying to help people when Hitler was assassinating. They would do anything: buy a passport, use someone else's passport, just get out. That's what happened.

But the court was not sympathetic and he went to jail, not for long though. How long?

He was there a few months, and then there was an appeal. Eventually they let him out.

I asked him about this in a phone interview in 2005, and he didn't want to say anything about it. But I know that he had some kind of religious conversion when he was in prison. He had early on spoken about being a Catholic. And in fact he still called himself a Catholic in our last interview in 2010.

It was an evangelical wave that took over the whole country, because of the war. There was no solution. If you can't go out, your only solution was God. They saw people who were praying and became calmer, at peace. The country was destroyed. The tradition was destroyed. People were crossing the river to Brazzaville, going to Angola. People just started running away from everything. So Papa Wemba found himself in prison for the first time in his life. He thought he was doing something good, for the people, and then it turned out to be wrong. He thought he had his back against the wall and he didn't know what to do. So now people come up to him and start talking about religion. “Just give everything to God and you will get peace.” He believed them. That's how Papa Wemba converted himself into an evangelical.

Wow. As I said, he still considered himself a Catholic, but you think this conversion was sincere.

It was sincere. Even his girlfriend, Sharufa, the one who came to him. She also became very religious. I think her new husband is a pastor actually. But this was a pretty large movement, and it really shook Papa Wemba’s circle. He did not become a Christian singer, though he did come out with one Christian song.

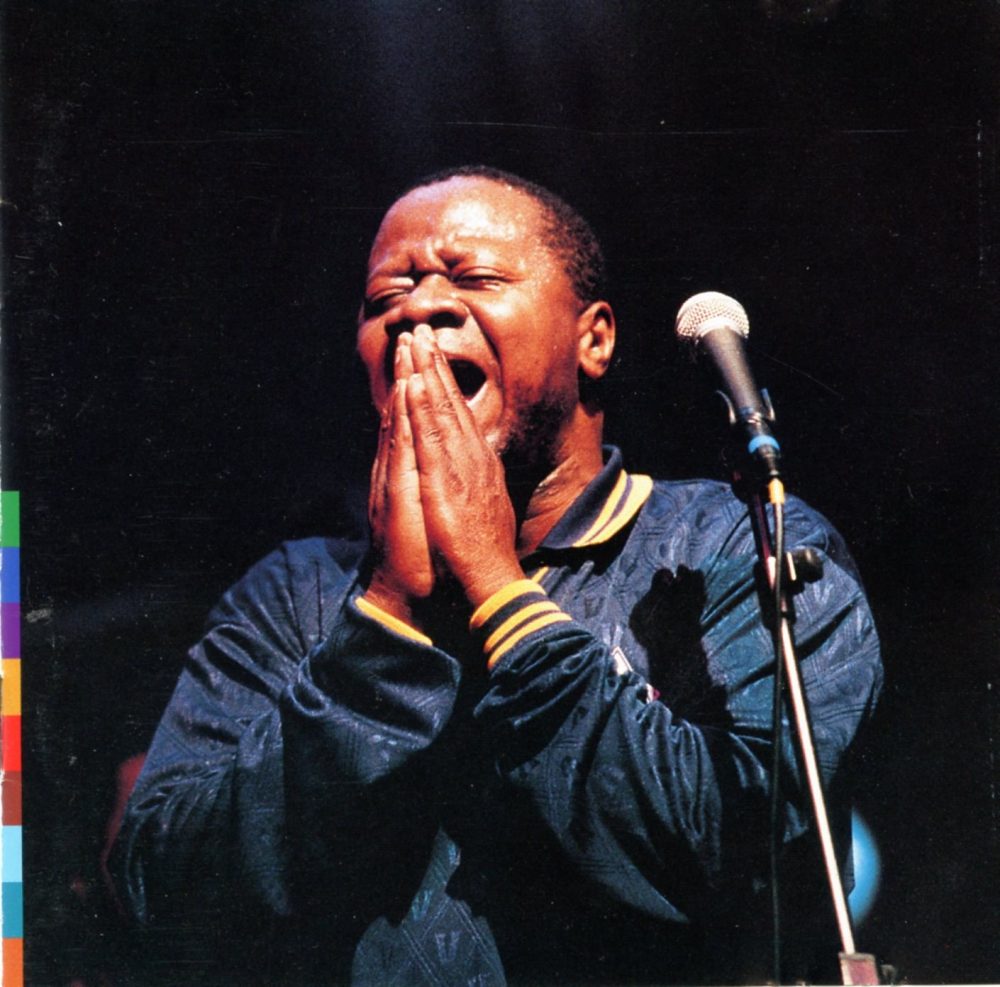

Well, he didn’t have a lot more years to live. He died in 2016, on stage at a concert in Abidjan. He was 66 years old. And I always remember what he said in our last interview, about how much he loved performing.

Papa Wemba: I love this. I love to tour and do concerts. Even in small rooms. I adore it. I can come with 10 people in the audience, with the same energy, and the same determination. Even if it's thousands of people at a festival, it's the same energy, the same force. Because for me the stage is one of the places where I free myself. Totally.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles