Ethio-jazz is at a tipping point. Musicians such as Meklit and Jorga Mesfin are bringing back the genre and adding their own spins on it. This time, there is real potential for the Ethio-jazz reservoir to flood world music.

In the ‘80s Ethio-jazz musicians did not get to share their vision. Now, the growth of Ethio-jazz is a return to a chance moment of cultural exchange between Armenians and Ethiopians.

Orchestras in Ethiopia had their origins in Jerusalem, which housed refugees from the Armenian genocide from 1915. In 1924, the former Emperor of Ethiopia, Hailie Selassie, previously known as Prince Ras Tafari, was visiting Jerusalem and came across a marching band of Armenian children orphaned by the genocide. He got permission to bring the band back to Ethiopia, where it became the Royal Imperial Brass Band. Afterwards, orchestras often accompanied singers.

In the ‘50s under Selassie’s empire, Ethiopian musicians began to fuse Western jazz with traditional folk music. Thus began the 17-year-long “Golden Age” of Ethiopian music, in which Mulatu Astatke, Mahmoud Ahmed, and Hailu Mergia led the country musically and thrived on a platform to express their musical artistry.

However, the movement wasn’t able to spread as much as it could have. Once the Derg, the military junta under Mengistu, took control in 1987, emigration was nearly impossible. Musicians couldn’t play their music on an international platform; they could hardly play on a local one, as the Derg imposed curfews and Ethiopian nightlife suffered when the clubs closed. That didn’t mean there was no music in Ethiopia, it just meant the cultural hubs contributing to the development of Ethio-jazz closed. In place of Ethio-jazz was a flood of cheap keyboards and synthesizers, from the alliance between the communist government aligned with Russia. And although the Derg collapsed in 1991 with the fall of the Soviet Union, as Meklit stated, “You can’t actually pick up where you left off.”

That’s why it took some time for Ethio-jazz to gain momentum. But there were some Ethiopians carrying Ethio-jazz in their back pockets, who are now helping to strengthen the musical movement. While the Derg was in control in Ethiopia, Jorga Mesfin was playing with his Ethio-jazz band Wudasse in Atlanta. His U.S. residency permitted his practice to deepen so Jorga could be “bilingual in both the idioms of jazz and Ethiopian music.” Now, Jorga is the musical director of Mulatu Astatke’s African Jazz Village in Addis Ababa. Addis Ababa is livening up as a result of the Village, and folks are noting a musical surge, as demonstrated by the reopening of Coffee House, one of Addis’ oldest jazz houses, which now hosts the capital’s top Ethio-jazz players.

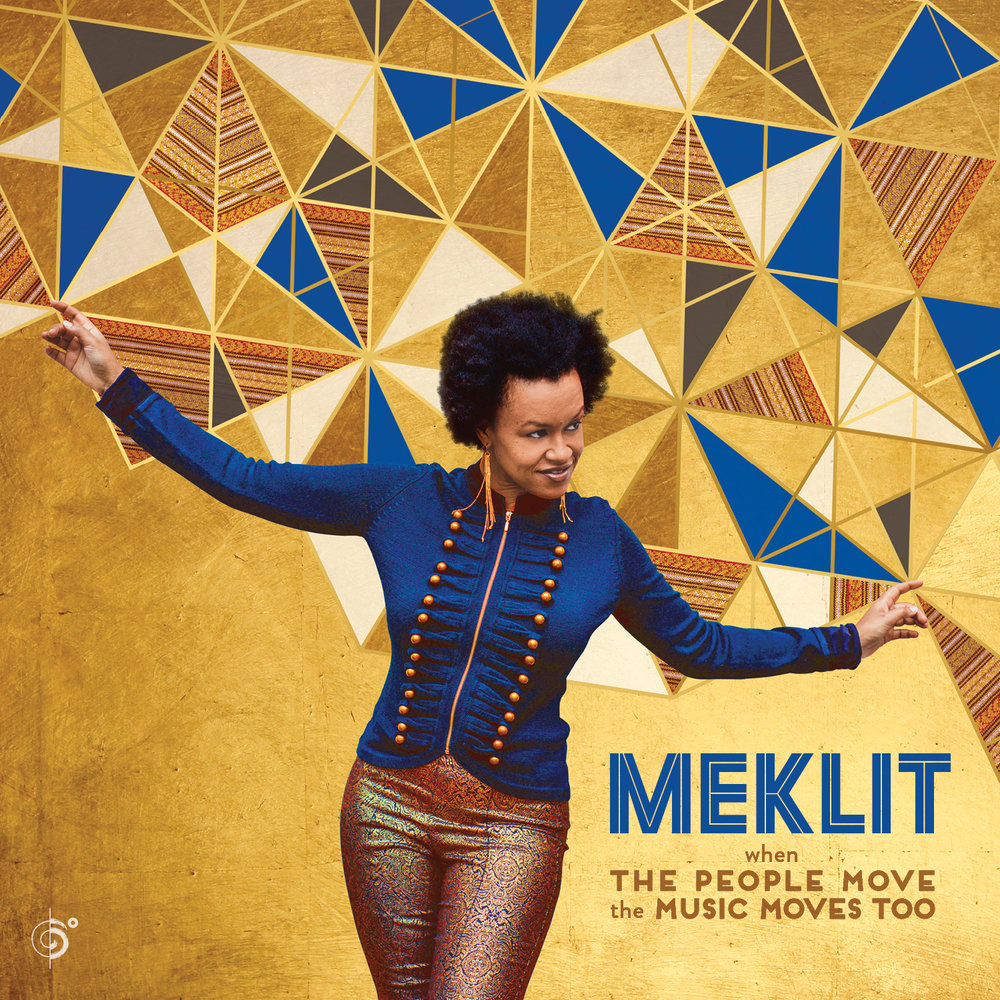

As Meklit was raised in Brooklyn, Iowa and Florida in an Ethiopian family, the process of adding to the Ethiopian musical canon happened naturally. “Ethio-jazz is a music that naturally can hold my journey,” she told me in an interview. Meklit started her musical career at age 25, playing Ethio-jazz as people played it in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Then she encountered Mulatu Astatke, the godfather of Ethio-jazz, who questioned her old-fashioned playing style after one of her shows and pressured her to adjust her style to push the genre’s boundaries. She now agrees with Astatke’s point: “This music has to keep growing and keep on evolving to remain current.” The individual journeys of artists such as Meklit contributes to the current resurgence of Ethio-jazz music. Now, Meklit blends the pop, jazz, and soul she grew up with into classic Ethiopian tunes. Continuing to innovate is especially important in this resurgence, because the first wave of Ethio-jazz, which had a promising beginning, was forced to a standstill.

In a time in which people are recognizing social patterns that must be changed, fueled by movements such as Black Lives Matter and protests, Ethio-jazz musicians I talked to hope to make an impact. They have more than just music in mind when they are belting notes or caught in the throes of a saxophone solo. Both Jorga and Meklit focused on their social visions. Jorga yearns to “express the wisdom of two giant civilizations. The African-American and the Ethiopian.” He says, “Ethio-jazz gives a glimpse of the side of jazz that is not reacting to a white supremacy racist power structure.”

Meklit articulated how Ethio-jazz can move humanitarian movements forward: “We’re just on the edge of seeing what Ethio-jazz can be as a global language… I think about films like Black Panther and this way that people [from] the African diaspora are so hungry for expanded representation and of looking at ourselves in this breadth of beauty and expansiveness and multiplicity.”

The resurgence of jazz nightlife, the vibrant state of the African Jazz Village and new experiments with Ethio-jazz by artists such as Meklit, Jorga, Samuel Yirga, and Girum Gizaw suggest that Ethio-jazz really is making its way onto the world music stage. Although currently small, the rise in Ethio-jazz today is culturally significant, and represents a renewed creative expression that wasn’t always available to Ethiopian citizens. If Ethiopian musicians continue to experiment with old and new forms of Ethio-jazz, there is no way of telling their global potential.

Meklit will be touring the East Coast in July, including New York. Click here for more information.

Related Audio Programs