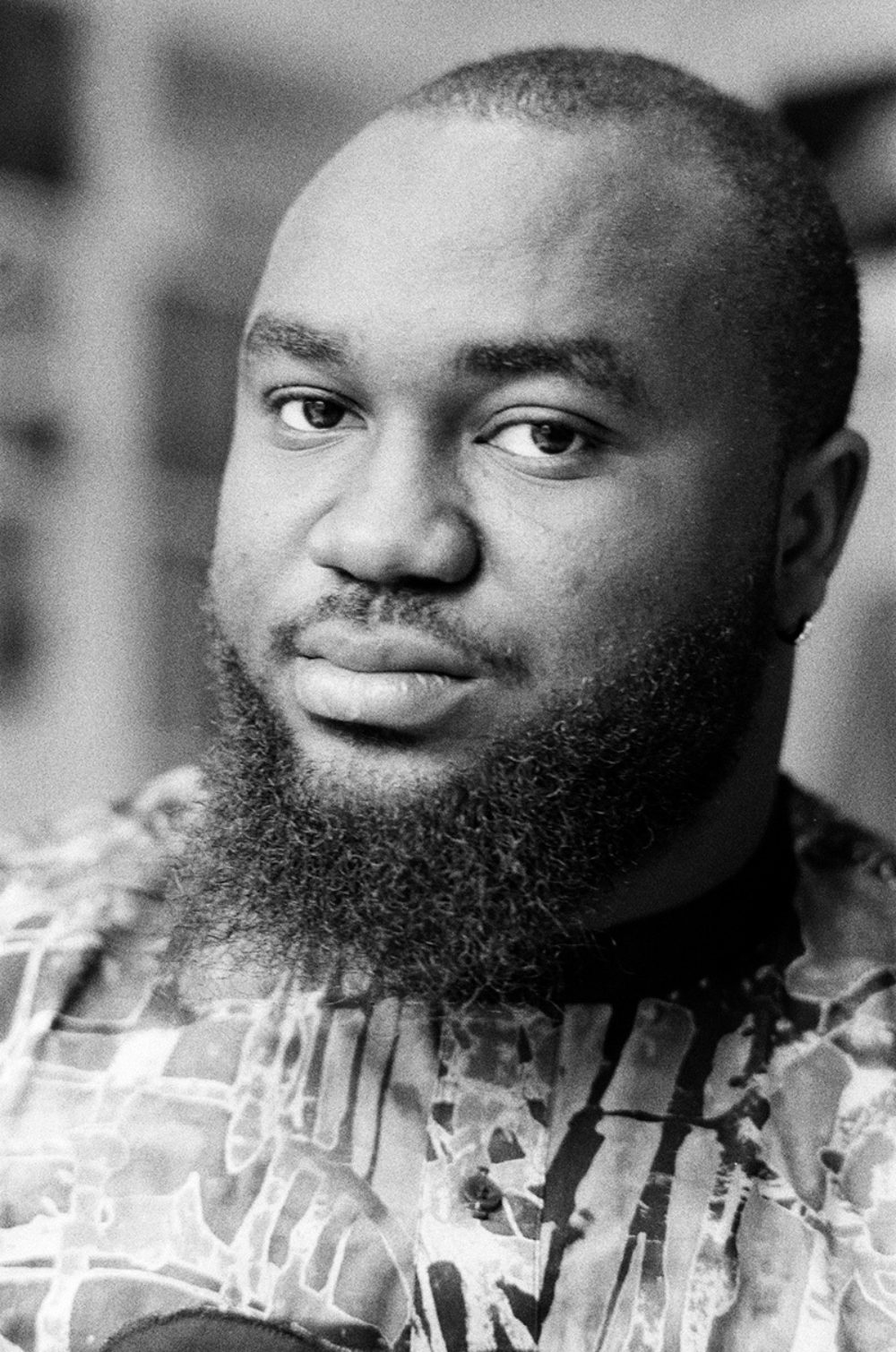

Etuk Ubong is a trumpetist, composer, arranger and bandleader from Lagos, Nigeria. Born in Akwa Ibom State in southeastern Nigeria, he was raised in Lagos where he showed early signs as a musical prodigy. He went on to perform with highlife legend Victor Olaiya and Afrobeat torch-bearer Femi Kuti. Today, Ubong leads his own band, and is among the most innovative, groundbreaking rising stars in African jazz. His 2020 album Africa Today was recorded direct-to-disc for the Night Dreamer label in Holland, and the album is featured on Afropop Worldwide’s “New Moves in Afro-Jazz.” In 2018, Ubong opened his own venue in Lagos, The Truth. Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Ubong over Zoom from Lagos to discuss all this and more. Here’s their conversation.

Thanks for speaking with us. I’ve been enjoying your album on Night Dreamer, it’s a great example of the potential synergy between jazz and contemporary African music. It's kind of a truism that jazz has roots in Africa, and of course there is a lot of great African jazz, but overall, jazz doesn't have a very big audience in Africa. Of course every place has its own story, and Nigeria I think has a special relationship with jazz, in part because of the legacy of Fela Kuti. I certainly hear that legacy continued in your music. So that's why I wanted to talk to you.

O.K. Cool.

Let's start with some of your background. How did you become a musician in the first place?

Basically, my mother was one of my greatest influences. I'm from this kind of Christian religious home, a half-religious home. My mother was a committed and devoted Christian. My dad was a traditionalist. And then my grandfather was a chief priest. So a bit of Christianity and the other way as well. My mom used to tell us, “We need to go to church,” and then everybody goes to church. So at church, I found myself on the conga drum at some point, and then I developed an interest in playing the drum set. But then I think I stayed with the conga for a while, until a day when the church got a new trumpet. They invited a trumpet player to come and play that day. After the church service, my mom took me to the trumpet player and she was like, "This is my son." You know when someone hands you over to somebody else. "This is my son. I need you to teach him the trumpet." And that's how my journey into music and the trumpet started professionally.

Interesting. How old were you that?

I was a teenager. I started playing professionally when I was 14.

Wow. You know, trumpet was the first instrument I wanted to play. But I ended up playing guitar.

Oh man, the trumpet is one of the most beautiful instruments. Guitar is cool, but…

Well, that's how you should feel about your instrument. You grew up in Lagos, but your family came from the south, right?

Yes. I lived all my life in Lagos except when I had to go study in South Africa at the University of Cape Town. I did that for about a year. I also studied a bit in Ibadan in Oyo State, which is in the west. But I spent practically all my life in Lagos.

What made you go to Cape Town?

It’s the same story about jazz music, man—the transition of Fela from Abeokuta to Lagos, from Lagos to London. The same thing led me to South Africa. Actually I have always dreamt of being a jazz musician. I grew up listening to the likes of Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, a lot of others. Clifford Brown was my favorite. Basically, in Nigeria, the jazz culture here is not functional. I'm going to use that word. It's not functional. You can't get a jazz education here in Nigeria. The best you can get is a classical education, would you have to go to the Peter King College of Music, which the MTN network sponsors, and offers scholarships. I had a scholarship to go study there, so this is how my journey started.

I really wanted to study jazz, but unfortunately, Nigeria couldn't offer me that. All I got was this rudimentary theory of music, which I learned from the Peter King College of Music first. And then I went to Ibadan to study a bit of music tech, but I still wasn't satisfied. I needed a proper jazz study. Then I got a scholarship to study at the Music Society of Nigeria. It was strictly classical music. Then four months before I got my diploma in classical music, I got admitted into the University of Cape Town, South Africa and College of Music.

I couldn't defer my admission in South Africa because they gave me the impression that they needed me. They needed a trumpet player. So I had to go study jazz music, because that's the only place in Africa where you can get such a level of education, up to standard.

Sure. That’s the home of Abdullah Ibrahim, Basil Coetzee and so many others. That must've been a great experience.

It was. But the transition was already taking place in Lagos, to be honest. Before I got to South Africa, I was already playing beautifully well. I was able to integrate a lot of changes. I started a jazz band in Lagos. I played some gigs. I started writing some music. So I think my transition came from when I started playing with Femi Kuti at The Shrine. But before that, I played with Victor Olaiya, the highlife genius. Fela had also played in his band.

And Tony Allen too.

And Tony Allen. Yeah, man. So that's a big deal. I played in Victor’s band and then I moved to Femi Kuti’s band, and while I was in Femi Kuti’s band, I really got to really delve into Afrobeat and what Afrobeat reflects about African history, the black experience, all of that about Africa and the continent itself. So I met the likes of Hugh Masekela. So that was a turnaround for me because then I started to learn about my culture, my heritage. I started thinking about how I could reflect my culture being an African, being a Nigerian, also being an Ibibio man. So by the time I got to South Africa, I was already writing more African music.

It was beautiful because I still had the opportunity to learn the jazz studies for a while, but then the change in the transition came from there, because it was more like "Man, know yourself." So at that point I regained my consciousness, and it was about Africa. And that's what I reflect.

So Victor Olaiya and Femi came before Cape Town.

Yes, I went to Cape Town in 2015-2016.

I'm curious about your time with Victor Olaiya. What was that experience like for you?

Man, it was a life-changing experience. That was the first band I ever played in. And that's when I started playing professionally, on that stage. We used to play two nights a week, every Wednesday night for band rehearsals and Saturday nights at the Papingo Nightclub at the Stadium Hotel in Surulere, Lagos. Victor Olaiya owns the nightclub there. Or he did. He’s late now.

I got into the band through a guy named Baba Wise. Baba Wise used to be a tenor saxophone player with Fela back in the day. Then he started this company for fixing and repairing horns, saxophones and trumpets, all sorts of horns. So I took my horn to his place, and after fixing the horn, he told me to check it. I started to play chromatic scales. And I think I was playing at about 250 BPM, or even faster. So I started playing, and the guy was like, "Wow. You sound really amazing. Where are you playing?" And I said, "Nowhere."

And he was like, “Who trained you on trumpet?” I told him, “Victor Ademofe taught me the trumpet." And he said, "Would you like to play in a band?" And I said, "Yeah, I don't mind."

“O.K., next week Wednesday, come here at 1 p.m. You're going to start playing in a band." And I got there at 1 p.m. He took me to the Stadium Hotel, and I played the trumpet. What happened was I got to the rehearsal section a bit earlier than everybody. The record was playing. I think it was “Trumpet Highlife” or “Moonlight Highlife,” one of his songs. And then immediately, I transcribed that trumpet part and I just played the solo. Victor Olaiya heard it from his office, and that was how I got the job.

It was beautiful because it was more like an institution for me. I got exposed to the music and the life of Bobby Benson, Rex Lawson, Zeal Oniya, Roy Chicago, E.T. Mensah, even Fela. Victor Olaiya told me about those people, their stories, his experiences with them. It was more like living the life back in the ’60s, like you are experiencing what happened in the 1960s, 1970s. And it was fun, because those are still part of my major influences to date. That really affected me a lot. I played in the band for about three years before I played with Femi Kuti for about two years. So it was beautiful. I had the best education playing as a side man with Victor Olaiya, because I was able to sing. I was able to play. I was able to give them a show, man.

What a great experience! And by that time, Victor had done it all. He had mentored all these great artists.

Man, I'm so lucky.

Tell me about playing with Femi. I've seen the band a number of times, and boy, that is a hot horn section.

Femi is a genius. Femi is beautiful. He's one person who taught me the art of being very disciplined. He's a very disciplined musician, and a very disciplined human. The music is beautiful, as you have experienced. The horn section is amazing, very, very hot, and his presence alone is something else. I learned a lot from Femi at The Shrine. He's very determined and focused and passionate about what he does, and that also was a great inspiration for me. The band is amazing as well, because like I said, the discipline. You just need to be on point. You need to be punctual. You need to get your parts right. You need to be able to do the things you need to do. It's more like you're going to school. Because you go to the best school, doesn't guarantee that you come out being one of the best.

I was really determined and I am very passionate about music, the trumpet and everything I do. I was able to ask Femi a lot of questions, how he does his things, how he composes his music. I watched him practice for a while, so the experience was really beautiful—being in that space, experiencing Afrobeat. The great thing is it was like experiencing Fela as well. Because he experienced Fela. He played in Fela’s band, so I got to know about that. Unfortunately, I didn't stay long, just about one year, eight months before I went to study in Cape Town. And then I started my own band afterwards.

When the Cape Town opportunity came up, you had to drop everything and go there, right?

Yes. I had to do that. But I already had plans. Like I said, the transition happened while I was there, because I knew I was going to become a pan-Africanist, a concerned African, and a concerned citizen of the world through my music. But the greatest inspiration I got from Femi was The Shrine, actually. The day I stepped into The Shrine, it felt like a new world. It felt like something different, a world that embraces humanity regardless of race, culture, class. You know that’s something very beautiful. I said to myself, "Someday I’m going to have my own space where humans can come to dialogue in optimism for a better world." So that was part of my greatest benefit from the band. So after I left Cape Town and came back home, I started my own band and started touring. Eventually, I was able to save up and start my own place.

I want to talk about your venue, The Truth, and about your band. But first, your biography mentions ekombi as an important element in your music. Can you tell us what ekombi is?

Ekombi originally is a dance art form. It's from Ibibio, from the southern part of Nigeria. The Ibibios were more like a nation unto themselves back in the old days. We were kind of half Bantu, that's the origin of the Ibibios. Like I said, reflecting my culture and heritage, that's something that comes to me naturally. That's what I reflect. I need to talk like an Ibibio man; I need to think like an Ibibio man as well. So my music needs to have such elements. It's a dance form, and then applying the dance form and the style and the group that goes into the dance form is part of the things that I play now. And also part of the elements that comprise my compositions, and my rhythm section, actually. It's basically reflecting the Ibibio culture.

When it came to forming your own band, what was your concept? What instruments did you want to have? What was the overall idea?

The band was going to be one of the greatest bands in history.

Well, that's a good start.

Yeah, we work so hard. So now we play three nights a week, and then I think we might start playing four nights a week very soon this year. That's a lot of work, man. And then touring together. That's beautiful. No complaints. That's what I want to do with my life. The band is comprised of a big horn section: baritone saxophone, tenor saxophone, trombone, trumpet. Then the rhythm section is comprised of the drummer, the conga player… One guy plays plays the conga, the bongos and the giant conga. And then a percussion player plays all the toys: shekere, wood block, the triangle and all that. And there's a piano player as well, and electric bass. Then I have two dancers who also do backing vocals as well. And myself, I play the trumpet, I play the flugelhorn, and I sing. I play the organ as well. I direct the music, compose the music and arrange the music.

That sounds like about 12 people. A big band.

Yeah.

Let's talk about this record a bit. Now this is not that Lagos band, is it? This is a project you did with musicians in Holland, right?

Yeah. This is Africa Today. It’s a beautiful piece. The fact that I also recorded it with Night Dreamer was a big deal for me, because you hardly come by musicians recording direct-to-disk in the present day. You know, it used to be the old-fashioned style of recording back then, which I really dig a lot. When I listen to the records back in the ’60s and ’70s, they sound really amazing. Miles Davis records and all that. Even Fela Kuti. So when I got the opportunity to work with the label I couldn't say no. I took the music to the Netherlands with one of my musicians from Lagos. Some of my musicians from London played as well, and then the other part from Netherlands.

Africa Today reflects the present happenings in Africa, and not just the present happenings in Africa, but also the past events. And how they have affected today's events, all the present events in Africa, why Africa is where it is today, and all that's been happening.

Africa's got a very beautiful history: the good, the ugly, and the present. The good part I believe is that Africa—you might not agree with me—but Africa is the mother of world civilization. I say civilization started here in Africa. I have my facts though. Before the Greeks and the Romans and all them came into Africa, we were already practicing a whole lot. We had our civilizations. We were already creating, constructing the architecture, the designs, the pyramids. We had medicine as well. We had our forms and our modes of writing as well. So that is one part of West Africa, and the Arab influence as well from Egypt. That's the beautiful part: how we civilized the world and how we changed the course of civilization.

But then, where it got wrong, after the invasions and all that, we had a role to play in it. Our kings as well then, our rulers as well. This history isn't too good. Because when you think about it, they came and brainwashed the people. They gave people weapons and gunpowder and all that, which doesn't make sense to me. But then, where we are today, we have the potential of becoming one of the greatest continents in the world. We've got oil, we've got diamonds, we've got everything. But then our leaders are so greedy. Our leaders are the problem of Africa. They are highly corrupt. If the leaders are corrupt, they hold the funds, they hold the power, then there's a problem, man. Because all that common wealth doesn't get to the people. The leaders keep on exploiting the people.

After 60 years of independence in Nigeria, we still don't have good roads. We still don't have security. Boko Haram is a problem for us today. The educational system is bad. The health care system is not functional. The problems we have with COVID-19 today are a reflection of the healthcare system not being functional. You see, all of these problems are the basic problems that we shouldn't be facing after 60 years of independence.

When leaders are corrupt, it creates a culture of corruption. That’s hard to undo.

Exactly. So it's not just a Nigerian thing, but also the rest of Africa. So like I said, in Africa today, they kill our people, they burn our houses, they keep people starving. There's hunger in the land, poverty, starvation and all that. Yet the leaders are not doing anything. And you see a pastor getting a private jet. It seems like religion is the order of the day, politics is the order of the day. Those are our top celebrities now, which is really, really sad.

So until we get to that point where we eradicate corruption in Africa, maybe at that point there might be changes. Maybe we might start singing about love then. Maybe we might start singing about something more beautiful at that point. But for now, we need to focus on the problems of Africa now and make people aware.

So the beautiful thing about this album is how it educates people and makes them aware about the happenings in Africa. Too many people really don't have that experience. They don't know what's happening in Africa. They don't know the African history, even some Africans here, because the majority of the schools don't teach the history of Africa, which is really sad. How are you going to progress when you don't know your history. So I have taken it upon myself to make sure I do this through my music. I need to make sure the Black man knows himself.

For our recent program on Nigeria, I spoke with Ade Bantu of the band BANTU, and he was too highlighting the problem of not teaching history in schools. He too believes that music can play a big role in correcting that.

Let me ask you about a couple of the songs on this album, starting with the first one, “Ekpo Mommomm.”

My granddad is Ekpo Mommomm. He was just a beautiful young man back in the days when there was farming, hunting and all that. He went missing for about six months. When he returned, he explained that he was in the sea for three months there with the spirits. This is a true life story man. They called him Ekpo Mommomm, which is a ghost, because, literally, he was a human and a spirit as well. He had the ability to appear and disappear. He played pranks on people sometimes. You might be in the garden with him and then, you can't see him anymore. But then he picks you to like, “O.K., I need this one to see me." And then you are the only one in that garden can see him. So it's stuff like that. But then he did beautiful things with his power as well. He healed a lot of people. He did amazing things like curing people from illness, so he was a great guy. I wrote that song in honor of my granddad, Ekpo Mommomm.

How about the song “Spiritual Change”? That's a very beautiful, cooler song in the mix.

You know, we had great people who tried to change Africa into the beautiful Africa, into what Africa used to be like, and even more. We had Kwame Nkrumah, who tried to unify the spirit of Africa. That's the first step. If you can unify Africa, then 80 percent of our problems are solved. So we had the great Kwame Nkrumah. We had Thomas Sankara, who was a very beautiful president from Burkina Faso. We had Patrice Lumumba from Congo with the Belgians. You know the story, right? We had Stephen Biko from South Africa. We had Nelson Mandela. We had all these great people who were trying to make a change in the society. Even Malcolm X in the diaspora as well. We had Martin Luther King, Marcus Garvey. We had all of those people.

They came. They died. But they lived for the people before dying, and their legacy still continues. Unfortunately, the world has changed. People have been distracted. But I'm happy that in the present day, the Black man is aware. They are aware of the happenings in the world, and they are not ready to back down We are working hard. We are striving hard, which is a change. We’re striving now to end segregation. We are striving to make sure racism doesn't exist. It might not be in our lifetime. It might be in the next 500 years, but that's the change we should be all about. We once had a man like Nelson Mandela, a man like Fela Kuti, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, and all those people.

Those people were once the change we had, so I want to be the change today. We all should be the change. This isn't just an African story. Europe has got its own problems. United Kingdom, they've got their own problems as well. Even the Americas. So we ought to be the change, man. If we want to change the problems and happenings in the world, we ought to be the change. Everyone should be part of it.

I love the last piece on the album, “Etuk’s Ritual.”

Yeah, man. “Etuk’s Ritual.” I'm very spiritual. I believe in what I believe in. You know, music is more like my religion actually. It's not just music anymore. “Etuk’s Ritual” came from me and the whole concept of truth. You know my space is called The Truth. Once I'm there, it's a world that I created, not just for myself but for humanity as well. You know, a lot happens there. It's a reflection of what came up, the band, the music and all that. It reflects Earth Music. That’s what I call my sound, Earth Music.

You mentioned that Ekombi is an important part of your rhythm section. Can you point to places on the album where we hear that?

You can hear that on "Mass Corruption.” You can hear that on "African Struggle." You can hear that on "Spiritual Change." You can hear the feel of the rhythm section, but not just the drums, like the whole ambience of the music from “Etuk Mommomm.” [Sings]. So it's very dramatic and it takes you straight to Africa, and then from Africa it takes you to Nigeria, and from Nigeria, you find yourself in the Ibibio land.

One thing I notice about this album is that it tends to feature ensemble horn arranging more than soloing.

That's true.

Is that part of your overall band concept or is that just the way it came out on this album?

That's basically the way it came up on the album, because writing the music, I try not to alter what comes. About 99 percent of my compositions are not things I think about. They just come. “Africa Today”—the lyrics, the rhythm section, the groove, everything came from a dream. I woke up and I recorded it immediately. I called the band together the next day. Boom. Straight from where it came from to the disk.

But I'll just say, watch out for the next album. There's a lot of solos, improvisation and all that. But that's the way it came for the Africa Today album. The writing, the way of writing is more of that ensemble feel. It's just the Black experience, man. You can feel a lot from the music. You can feel the things I said about the happy place where we used to be, the mother of civilization, the agony, which is the pain, how it happened with imperialism, colonialism and all that, and then the present day, why Africa is where it is today. Then I'm also beginning to sing and write songs about the future as well, the possibility of how we can unite as humans and how we can be great as Africans. So that's what people should expect from the next album, which is going to have a lot of improvisation as well.

Are the recordings of your own band?

You will hear that in a couple of weeks. We're releasing a new single which is called “I Waka Dey Go.” “I Waka Dey Go” talks about the current happenings in Nigeria today. Nollywood is like our own kind of film, our own kind of Hollywood, the drama and all that, and the struggle. Man and woman struggle every day to put food on their table in this hard time, because the government, the system, doesn't make it easy for you to be able to even have three square meals, or even two square meals sometimes. It's so hard and difficult. The poverty rate has actually increased, especially in this Buhari regime. And then, it talks about police brutality as well. Last year, we had a great movement here called EndSARS [Special Anti-Robbery Squad.]. It addresses that problem. And then the government keeps stealing from us. We need to get vaccines. COVID. It's just crazy when the system does these things to you, the system that's meant to protect you and give you a better life is now making it difficult for you to even live. So yeah, this song addresses all of that. But it's also very interesting musically. It starts with a trumpet part and it ends with a trumpet cadenza.

Great. I look forward to hearing that. In our December show, we talked a lot about EndSARS. We also talked about the changes in the music. You know, we've been covering Nigerian music for over 30 years, so we've seen a lot of change. And now today, these young artists—Afrobeats, Naija pop, whenever you want to call it—these artists are having a global impact. So when you look at the scene now, how does your music fit into the scene?

I see it this way. The world is turning around, going back to the old-fashioned way, going back to the ’60s, the ’70s. And that's actually happening now. It's happening in Nigeria. With Afropop being very dominant globally, I come to realize that live music is beginning to take form again. There's more like a revert already. With The Shrine, where Femi performs twice a week, it's always packed, and they also host one of the biggest festivals in Nigeria, which is the Felebration that happens every year. I can say this for my own club as well, The Truth. It's surprising to see that the working class, the young people between the age of about 19, 18, up to about 45, you see a lot of them come to the club, to come listen to the music, vibe to it, so they’re really into that culture of live music coming back.

Back in the ’60s, we used to have a lot of clubs where all these great musicians performed. Bobby Benson had a club. Roy Chicago had a club. Victor Olaiya. All of those people used to play at clubs. Lagos was just like 52nd Street in New York where you have a lot of jazz clubs. We used to have that kind of nightlife back then. But then, after the Civil War broke out between the Nigerian and the Biafran people, nightlife started to degenerate. Now it's coming back. The culture is coming back. But the young folks are not smiling. They're not joking. Because they want to go for it. They want to be able to see action.

My music, which I call Earth Music, has the influence of jazz and Afrobeat. It's going to be able to stand on the same level with the mainstream, the same level with the Beyonces, the same level with the Burna Boys. the Wizkids… Because it's about the groove. It's about the message. It's about the feel. And then the African experience, like I said. Trust me, what made Hugh Masekela what he was? It was because when Hugh Masekela got to America, the likes of Coltrane, the likes of Miles Davis and Art Blakey told him, "You need to play African jazz, man. You need to reflect Africa.”

And then Hugh Masekela becomes great automatically. You can name Hugh Masekela. You can call Herbie Hancock. You can name Fela Kuti, these great people who had their identities. So with my kind of music, and the live music happening now, it's just about the culture. Your culture needs to stand out, and what makes your culture stand out is your identity, who you are. So it doesn't sound like pop. It doesn't sound like rap music. It sounds like Africa.

I like your vision. And I like what you say about live music. There's nothing like the feel of a live band. To end, tell me a little bit more about your venue, The Truth.

Well, The Truth is the truth! It's located at Surelere. I think the capacity is about 500 people standing, maybe about 300 seating. It's a very cool venue. It's beautiful. You come into The Truth, and it makes you feel like you're in Africa. You are in the motherland. Yes! The first thing you see: You see Fela Kuti. You see Thomas Sankara’s and Kwame Nkrumah’s pictures. You see Malcolm X and all those great people. Then you start seeing the masquerades. So that's the culture, you being in the Motherland.

Things that the current civilization makes you see as diabolical and bad, you will see the truth and it's going to look good. You're going to appreciate the essence and the value, and then you get to know this is your history. This is where you came from. This is it. So that's the feel you get from The Truth. I play three nights a week. Every Tuesday is our band rehearsal which is open to the public. Then we have our ritual night every Friday night. Then we have our Sunday commune. And we do this festival every year: The Truth Festival. Once a year. It happens in November. We adjusted to last year in November. We are striving to do number three this year.

So the club's just been opened three years?

It will be three years in November.

And it's working? You getting good crowds?

Yes. People are coming. We’re packing out some of the nights, the majority of the nights. An interesting part, and the interesting thing is we usually get a lot of different people. The story has gone wide so that when people in the diaspora come to Nigeria, and they have to be in The Truth. We’re seeing a lot of faces from the diaspora. And then the class thing is not there. You can't differentiate between the rich and the poor.

I look forward to visiting.

You will. You will. I'll be so happy to host you.

I look forward to it. We'll get out of this pandemic one of these days.

I believe we will. Things will turn.

You got to believe.