Eve Troutt Powell, is a professor of History and Middle East and Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. She is also a MacArthur Fellow and the author of A Different Shade of Colonialism, Egypt Great Britain and the Mastery of Sudan (2003: University of California Press) and co-editor, along with John Hunwick, of The African Diaspora in the Mediterranean Lands of Islam (2001: Markus Weiner Publishers). Her specialty is the Nile Valley, particularly the 19th century history of Egypt and Sudan. Banning Eyre interviewed her at the end of a year long fellowship at Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study in Cambridge, MA. Eve provided the principle voice in the Afropop Worldwide program, African Slaves in Islamic Lands. Here is the complete interview.

Banning Eyre: Tell us a little about yourself and how you came to study that Arab and Islamic slave trade?

Eve Troutt Powell: After college, I was one of the only people in my graduating class who had absolutely no idea what she wanted to do. So there was an internship at the American University in Cairo, for clueless wonders like me. I went to Cairo in the fall of 1983 with no Arabic, no Middle Eastern history, no background, nothing. I just wanted to be someplace different. I got there and couldn't read the street signs. I was a cultural illiterate. I had gone to Egypt thinking, "Okay, I'll see the pyramids. I will see all the ancient stuff." But it wasn't the ancient stuff that grabbed me. It was the street signs, and the crowds, and the rhythms of the city. Then I thought, "I need to know this city. And I need to be able to read Arabic, and I need to be able to live here, because this is such a powerful place.”

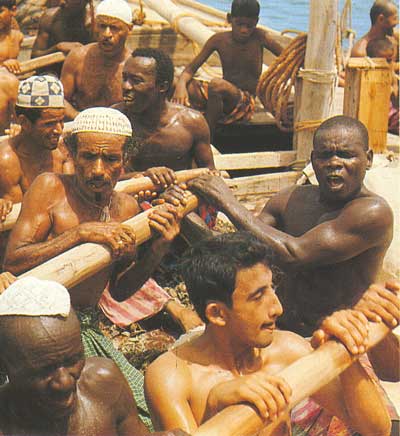

Slave servant in Egypt

B.E: What do the Koran and Shari’a law have to say about slavery?

E.T.P.: Okay, I’m going to begin by saying that I am not an Islamic specialist. But my sense, from what I have gleaned from my research, is that there are several interpretations of what Islam has to say about slavery. There is the idea that has been promoted by many Christian or non-Muslims abolitionists that because slavery is in the Koran, because the Koran sanctions slavery in the sense that it regulates slavery, there are many who believe that that means that Islam condones slavery. That Muhamed the prophet, when the revelation of the Koran came to him, did not do enough to actually censure slavery. Another interpretation and one that I find much more helpful in understanding the relationship between religion and this Institution is that what the Koran does is to regulate something that was huge and widespread in pre-Islamic, Arabian society, and that it actually tried very much to limit the impact of slavery and to create a world in which slaves had rights, and where there were limits to a master's rights over the slave.

Domestic slavery

The real question that comes out of that though is: What does Islam do towards the abolition of slavery? That is a huge question and one that I think we will have to keep working on and thinking about. Because there is a difference between the Koran itself, the Shari’a, which is Islamic law as interpreted by Islamic specialists, jurist consuls and scholars. There are many who say there's a huge difference between the Koran and how it has been interpreted legally over the centuries. Which means that there are some, like the wonderful Mauritanian scholar Mohamed Diakho, who has a book in French called L’Esclavage en Islam, which says that the Koran actually does everything it can to actually get rid of slavery, and that it is later interpretations of the Koran which, sort of ceding to the powers that be in the slaveowners that were, were complicit and complacent about slavery. So I like that idea. I think it is more workable.

But, some of the basics. The Koran says slaves do have certain rights. They have the right to protest against certain kinds of mistreatment. They cannot be beaten, for instance. And they can go to a Shari’a court in order to protest this, and can ask for manumission in those cases. If a slave woman has a child with a master, and the master recognizes this child as his, then she is known as umm al-walad, the “mother of his child.” The child is not a slave. In other words slavery is not inherited. It is not congenital as it was in American society. Just because your mother is of a certain status doesn't mean that you are of a certain status, if the father, the master, recognizes the relationship. And often, this did happen. Often the children were recognized. Now this is not to say that this was not difficult for many slave women. It was. So that is one thing that Islam does. Another limitation, though, is that slaves could not testify against masters in court, or the testimony of a slave did not count for as much as a free person. Slaves, I believe, could not inherit, or they could inherit if it was willed by the master, but it wasn't automatic in the way that it would be for family members. Manumission is something that the Koran encourages. It encourages slaveowners to free their slaves, and this is something that was very important in the prophet Mohamed’s lifetime as well. It was considered a good thing to do to free your slaves eventually, however, whether or not this happened institutionally, we will talk about as we talk more about the influence of slavery in history. Different cultures interpreted this differently.

Pearl divers in Bahrain

Now one thing that is very important about slavery in the Islamic world, is that it was not racial. It wasn't only Africans who were enslaved as it was in the case of Atlantic slavery, or slavery in other places. Anybody could be a slave as long as they were not a Muslim. Muslims could not be enslaved by other Muslims, but there was no racial stigma yet of slavery. And well into the Ottoman Empire, which is of course many centuries after the prophet Mohamed, there were Circassian slaves, Russian slaves. There was a whole spectrum of color of slaves coming from the Caucasus Mountains and then going into other parts of Russia, the Balkans. There were many Slavic peoples who were enslaved into the Ottoman Empire, and then you had people from East Africa and the Sudan, and Central Africa, who were enslaved. So by the time that you get to the real height of enslavement in the 19th century, that is the height for the Muslim world, you have a rainbow of slaves. But slavery means something different in each of these societies.

B.E: In the book you edited with John Hunwick, The African Diaspora in the Mediterranean Lands of Islam, there is mention of this interesting phrase in the Koran, a kind of euphemism for slavery, "those who the right hands possess." Is this the only way that slavery is referred to in the Koran?

E.T.P.: That is a really good question. But I don't think so. I think there are other references, because there are terms that come from the Koran about slaves. But I’ll have to look into that further.

B.E: You make an important point about the different kinds of people involved in Islamic slavery. Of course, we are really looking at just one part of the story, how the Arab and Islamic slave trade affected Africa.

E.T.P.: And how the African slave trade affected the Middle East. It is important to make the distinction because people goof all the time on this. By coming out of old Western concept of slavery, it is automatically assumed that slavery bears a certain kind of stigma, and it is really important to differentiate. Sometimes it did, if it was for Africans, but not necessarily the way would for African Americans. If you were Circassian in the Ottoman Empire, it was a wonderful thing in some ways to be a slave, because when you were freed, you could often reach the uppermost levels of power, short of being the Sultan himself. All the great viziers in the Ottoman Empire were trained as part of an elite institution. This was true within the Mamluk Empire as well, which was earlier. So you basically have different classes of slaves going on. And there were black slaves who could achieve those levels as well, so it is important to keep that in mind. You can't just exclude the Circassian slaves out of the picture, because there's a whole racial gradation that comes out. It is very complex, and we don't like to talk about how complex it is because we have a very black and white interpretation of slavery in this country, which just doesn't work in the context of the Middle East or East Africa.

Within the Islamic world, within the Middle East, there all kinds of racial gradations of slavery. They were whites. There were Abyssinians (Ethiopians). There were Sudanese. There were Nubians. There were Circassians. There was a whole complicated racial gradient going on which is very difficult for Westerners to wrap their minds around because slavery in the West, particularly African American slavery was black-white. Either you were black and you are enslaved, or you were white and you owned. This is something very difficult it seems for us, to intellectually divorce ourselves from our own racial constructions.

B.E: At a high level, what are the important things that distinguish the Western, European slave trade, from what was going on in the Middle East?

The Mahdi

E.T.P.: I'm going to start my answer from the 19th century. I'm a specialist in 19th-century history, and I think it also the height of the African American slavery institution that is so iconographic for us, and then the Middle Eastern one that we’re talking about, is the 19th century. So here are some of the differences. In the United States, of course, and the Caribbean, you had agricultural slavery. You had plantation slavery. In the Middle East, this was very rare. You did not see this certainly in the 18th and 19th century. So African slaves in Egypt would work in people's households, would be part of people’s families, would live in the household, would not have a huge community of other slaves around them, but really would be surrounded by the family of their owners. This is very different from what you have in the United States south, where you have large numbers of slaves on many plantations. The slave-owning family could often be the minority in many cases. The slavery that we’re talking about in the Middle East is much more domestic.

Now there was also a military slavery, which you do not find all in the west. There was a military institution along the Nile Valley in the 19th century. This was known as the jihadiyya, in which you had particularly Dinka tribes conscripted into the Egyptian army as slave soldiers. And this is an old tradition in the Islamic Middle East. It goes way back: having slaves be soldiers loyal only to the ruler. Of course, in the United States, the idea of putting guns into the hands of slaves would have been just totally anathema to the whole institution. It is exactly the opposite in the Middle East. And finally, again, you don't have slavery as an inherited status. It just doesn't carry that same weight through the generations.

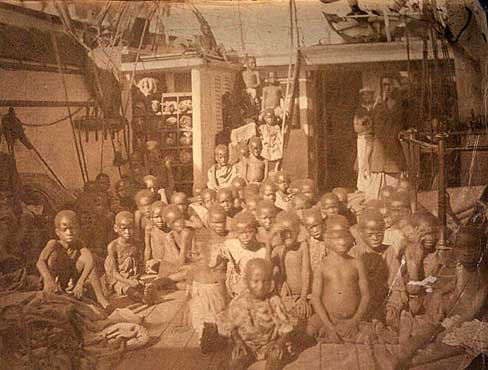

Slaves on the Indian Ocean Passage, 1868

B.E: In terms of numbers, what can we say comparatively about the European slave trade as posted the Arab/Islamic one? Was one substantially larger?

E.T.P.: I would say the slave trade in West Africa was much, much bigger. There is a lot of confusion of the actual numbers. Ralph Austin has tried to sum up all the numbers, but there is so much controversy over this.

B.E: I have heard it said the Arab slave trade was more of a steady trickle rather than I have a large flow, but that the Arab slave trade went on for longer, and so in the long run the numbers become more comparable.

E.T.P.: I don't think it ever comes close to the numbers we see in the West.

B.E: All right. One thing that interests me is that if slaves are not living in compounds with each other, but rather with the families of their captors, that really changes the ways and the extent to which their African culture and music can be preserved, shared, transformed in their new setting, and maybe the extent to which these things can have any lasting influence. You know, if you look at the New World from the perspective of music, we have Afro-Cuban music, Afro Haitian music, Afro Peruvian music, and so on. To some extent, these are driven by living communities who wish to promote themselves in part by attaching that "Afro" to they're identifying name. In the Mediterranean, we don't find Afro Iranian, Afro Turkish, or Afro Kuwaiti music. The author Joseph Braude spoke to us about musicians in the Persian Gulf, who everyone can see have African heritage, but that isn't part of their identity, their marketing, or even what they sing about. To what extent can we connect that result with their characteristics of the slave trade that you just described?

E.T.P.: I am not convinced that there are not communities of Africans who sort of carry on some of the legacy with them. I'm not sure that there aren't. I just don't know if we know how to find them yet. I'm not sure about that in the Nile Valley. I believe that there actually are neighborhoods in Cairo where there have been generations of people from the south of Sudan who could sing songs for you. You just have to be able to find them and get into them. This I know from some of my Dinka friends who have lived in Cairo for many years. But they certainly don't identify themselves as say Afro-Nilotics. They don't. That's true. I think perhaps in the Gulf it's a little different. Because the connections between former slaves and the slaveowning families are still very much alive. And so nobody wants to come out and sing these songs and proclaim themselves, talk about their slave identity necessarily, because the links are still there. They may not be slaves any longer, but it was their mothers or grandmothers who were, and they are often still living on the property of the former slave-owning families, and things are much more complicated. And this is something in countries in the Gulf, like say Dubai, where tourism is very important right now, and being involved in international marketing is hugely important, this is not something to publicize.

Aisha Khalife could tell you more about this. This is something I learned from her. You don't proclaim that because it embarrasses people. And what I have learned too from my interviews with southern Sudanese refugees in Egypt is that many of the questions that we Western listeners, looking for traces of slavery, ask, are really rude in another context. So we are saying, "Hey, let's hear about your slave history. What songs did you all sing? Got any Negro spirituals?" And we are missing the point, because there was no civil rights movement. The history of slavery, the family history of slavery, the personal history of slavery, is shameful. So people, when you approach it in that way, they are horrified. It is still an insult.

I think we are not asking the right questions. We should be asking questions about labor, and about labor communities. We have to change our vocabulary. We have to translate in a different way, because I have done this. I've gone right up to people and said, "Can you tell me about your past history? Isn't it wonderful that you and I share this legacy of slavery." And they are horrified, and I feel like such a goofy American, again imposing my own history on other people. So I think that is part of why we haven't yet found some of these communities. We need the language, and we need the connections to ask the right questions, and so people will let us in if they would be so generous, and then we can hear what they say.

B.E: That is really fascinating. Let's talk a little about the concept of Nubia. Many of the singers that we have focused on in Egypt and Sudan, Mohamed Mounir, Ali Hassan Kuban, Abdel Gadir Salim, Hamza el Din, all celebrate Nubia. They embrace this identity. What is that about?

E.T.P.: I will have to go to people in Egypt, because I think is a different legacy in Sudan. Nubia, in my understanding, represents a place of great Pharoanic legacy. It was such a treasure, that part of Egypt in northern Sudan was such an investment by the Pharoahs, and so much was located there that Nubians can really point to their homeland. “We go way back. We are the first Egyptians in many ways.” And this has always been my sense when I have gone to Aswan, which is the center of Nubian culture in Egypt, that people feel much more so than in Cairo that there the owners and protectors of a very, very old culture, thousands of years old, going back to the Pharaohs. There were Nubian pharaohs. Also, though, Nubia has become more fragile because of flooding of Nubia, or a great deal of Nubia, by Gamal Abdel Nasser, and the building of the Aswan Dam and Lake Nasser, which flooded all of these communities. I think the flooding started 1956 or 57. And this is something that Nubians are still mourning. Hamza el Din still has a lot of discussion about the loss of the place, and the loss of his own village, and I think Mohamed Mounir talks about this too. And yet the Nubians were the protectors of Egypt who were in some way betrayed by another kind of Egyptian culture coming in.

In Sudan, I'm not as clear about what Nubian-ness means, because you also have the Nuba Mountains. These are places where you have tribes that do this incredible wrestling and stuff, and have their own culture, which is not the same as what you have hundreds of miles north in Aswan. Also, and this is important, in Aswan, most of the people in Egyptian Nubia are Muslim, and this is not the case is in Sudan necessarily. So once you get further south into Sudan, Nubian identity is different.

B.E: So the people in the Nuba Mountains are Christians? Animists?

E.T.P.: They are non-monotheistic. Some are Muslims, but not all.

B.E: This is interesting. The singer Abdel Gadir Salim, as I understand it, took the folkloric music of Kordofan and Darfur and made it acceptable as urban music.

E.T.P.: Ah, so that's northern Sudan. That's interesting.

B.E: I'm wondering how that story dovetails with the history of slavery. One thing I've read is that as more and more coastal Africans became converted to Islam, there was greater pressure on slavers to move inland, so as to capture Africans who had not converted to Islam. Do you agree with that?

E.T.P.: I have never thought about it in terms of increased conversion to Islam affecting the slave trade. I have always thought about it in terms of the needs of Islamic Mediterranean countries, having a greater need to get further and further up the Nile in terms of controlling the resources of the Nile and also the people along the Nile. That has always been my interpretation, so I differ from Ronald Segal [author of Islam’s Black Slaves] on this point. Because those Africans, who may or may not have identified themselves as Africans in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and who also were very much a part of the slave trade in this part of the world, were responding to a need. I mean, you have to have a market before you can go in. So it's not just that so many people are converting. Islam has been in Africa for a long, long time.

I think what works more as the engine behind the increase in the African slave trade in Islamic lands is that first, you start with Muhammed Ali who takes over Egypt in the early 19th century, 1805, who is the vassal of the Ottoman Empire but has ideas about making Egypt and the Nile Valley his, and creating an independent or semiautonomous region, apart from the Ottoman Empire. And he sees the best way to do that as starting up the Nile. And so he actually starts an invasion of Sudan. In 1821, it's over, and he has conquered most of the Sudan. And the Sudan from 1821 until about 1884 is known as the Egyptian Sudan. And it is this push that really gets the slave trade going in Central Africa, Uganda and parts of Kenya, and much of what we now consider modern-day Sudan. This is what really pushes that. And in addition to that you also have a rival. So you have independent slave traders who start privatizing, and that's different. That's what you didn't have before. And that's what really gets the numbers up. You have Suleymane Pasha in Darfur, who creates basically his own slavery corporation, which rivals the Egyptians, and is selling to the Egyptians. And then in Zanzibar and Tanzania, you also have Tippu Tip, who is also doing the same thing. So I think it's not so much a question of: “ There are too many Muslim Africans." It's more like, "We need more and more and more people, because Istanbul and Cairo want them." Because Cairo is now selling to Mecca and the economics of slavery becomes much, much more sophisticated than it had been before. So I think that economic magnet that creates this market for slavery is what pushes things towards the interior, much more so than the question of conversion.

B.E: So this narrative of Abdel Gadir Salim bringing the folklore of Kordofan to the cosmopolitan capital, Khartoum. What does that tell you?

E.T.P.: Well, it suggests to me that culture is commodified and that artists know how to project themselves and figure out their audience is. It reminded me of being in Senegal last year and buying music like crazy in Dakar, and how so many people were writing off Youssou N’Dour and saying that he has gone totally Western. “He is no longer representative. He does what they ask him to do in Paris, and because of that, it doesn't sound what we want to hear anymore.” Meanwhile, all of the artists that I was hearing were rapping like crazy and clearly indebted to 50 Cent and people like that. So who people will claim as influences, and who people will accuse of being great diluters of culture, and to set themselves up as the representatives of culture, is always very interesting to me. But I don't know yet if southern Sudanese musicians, for instance, or Dinka, Zande, Nuer, or Nuba people have even hit that level of involvement commercially in Khartoum. I don't think this has happened yet in Khartoum. I know it has not happened yet in Cairo. It probably is happening more here in the States, with “lost boy” communities who know that there is an audience of people who really want to know what their experience is.

B.E: What about that expression "lost boys"? What is that about?

E.T.P.: I really can't stand that expression, and I don't know if they call themselves that. It's a missionizing term. It's a religious term, in many ways. The “lost boys” are young men now whose villages were attacked, or who were sold into slavery and escaped, who walked out of refugee camps in groups, as children, from Sudan into Ethiopia, from Ethiopia back into Sudan, or they walked into Kenya. But they walked thousands of miles to get to refugee centers or African capitals where they could get help. Their villages were destroyed. It's really quite sad. Many lost boys ended up in refugee camps near Nairobi. Others had to flee Ethiopia because of different wars going on recently in Ethiopia. But they have walked out of the Nile Valley in order to get help. They were orphaned. They were sick. Many died along the way. And then, they have been sponsored increasingly by major humanitarian groups like CARE, but also, most importantly by evangelical Christian congregations, who have seen these long treks in biblical terms, and have sponsored many of these boys to come to the states.

So they are in places like Iowa, places like Seattle, places like Georgia, and really sponsored by Christian communities as people who have had fight against all kinds of horrible circumstances, but also, and very importantly, against Islam, and against Islamic slavery. My objection is that there were a lot of girls along the way too, and their story kind of gets left out. And there's something about the terms "lost" and "boys" that keeps them in this perpetual childhood, and I've met some of these wonderful people, and they have survival instincts and sophistication which is miraculous really. It’s incredible. But they are not children anymore, so there is something about it, which in terms of my sense of the racial politics of this country, bothers me a great deal. Not out of any disrespect for them, but just the way it becomes packaged.

B.E: I think you’ve heard this collaboration between a young rapper Emmanuel Jal, who has that “lost boy” history, and Abdel Gadir Salim. Any thoughts about that project, the CD Ceasefire?

E.T.P.: I have listened to it. I really like it to tell you the truth. I think that Ceasefire is a nice CD. I brought it so that my kids could hear it, because I'm always talking about what's happening in Egypt and Sudan, and they know a lot of people from Sudan in Egypt, and so I bought it because I wanted them to get a sense that not everybody was fighting, and that there were these efforts. Also, I heard Emmanuel Jal interviewed on Fresh Air, and was really impressed with his responses and how really intelligent he is. He was a child soldier in the SPLA, and he's mentioned I think in Emma’s War, that book that's been a bestseller about the war in the Sudan. So it was so nice to hear him, a southern Sudanese person, being able to represent himself, and talking about his music. Now, I don't know how many people in Nairobi, in refugee camps, or in Cairo, are listening to this CD. I don't know if this means anything to them. You know, it's "cease-fire." I'm not so sure that that really has that much impact on communities in Darfur these days. But the idea is lovely, and it's a nice introduction for Americans, just to hear a Northerner and a Southerner actually make music together.

B.E: It was made at a moment of hope that turned out not to be so hopeful. It has transcendent meaning, though, for outsiders, because it gives us a window into a world we know little about. Maybe this is the time for you talk about Sudan as country, and about its difficult path to nationhood.

E.T.P.: Sudan has had one of the most difficult experiences in becoming a country of any country I know of—certainly in the Middle East or Africa—and this is being played out today. What we are seeing now is a country where nationalism has not worked, where there is a complex legacy of colonialism, not just a European colonialism, but also a Middle Eastern colonialism. In many ways, it is a failed State. But it is not a failed culture. It's a beautiful culture, beautiful cultures, but not a place where any government has been able to answer the needs of all of its people, and here's why.

I was talking earlier about Mohamed Ali and Egypt invading the Sudan, and the Egyptian armies who were led by Circassian leaders, so these are really Ottomans who spoke Turkish, who Mohamed Ali had brought in. He was himself an Ottoman general. So they were not connected so much to the people of Egypt, and certainly not culturally connected to the people of Sudan, and they were coming in first with the hope of getting more slaves and finding gold and also finding the source of the Nile, but secondly, with this idea of making a Greater Egypt. I'm imagining in the minds of people like Mohamed Ali and his generals who went south, having a country didn't mean being like the United States of America. It was a sort of empire, not the British Empire, an extension of the Ottoman Empire. You went in, you surveyed, you created a tax system, and then you pretty much left things alone.

But the administration that was set up was very unpopular among the Sudanese. By 1881, now you have a lot of slavery going on, and many Europeans in Sudan by that time who are helping Mohamed Ali and his successors rule this place. You also have Northern tribes furious at the taxation, at what they see as the un-Islamic practices of the Egyptian army, and there is a rebellion, this is known as the Mahdiya, after its leader Muhammad Ahmad who is known as the Mahdi, “the rightly guided one,” who is going to bring Sudan to a new Islamic reality, to a purer Islamic experience than that which the Egyptians had imposed. From 1881 to 1884, there is a long struggle between the Mahdists and the Egyptian army, and this is resolved really when the Mahdist forces encircle Khartoum, and you have General Gordon the famous British colonial officer, who is there to evacuate the British army. He is encircled and besieged by the Mahdist forces, and beheaded, and the Mahdist forces take over Khartoum, and it's a huge defeat for Egypt. And at the same time that this is happening, the British occupy Egypt, so that Egypt loses its colony in Sudan within months of becoming occupied itself by Great Britain, and this is why the experience of nationalism and Sudan is so sensitive and so interesting for Egyptian history. Because what you have is a colonized colonizer, so Egyptian nationalists are calling for independence from the British often at the same time as their calling for the recolonization of the Sudan, and this is all goes on in the late 1880s and early 1890s.

Meanwhile, the Sudan as we know it in its present borders is run by first the Mahdi and then by his successor the Khalifa. And for 14 years, it is pretty much an independent Islamic region. There are parts in the South which have not been colonized, places like Equatoria, where there are many Dinka tribes. These had been places where there had been a great deal of slavery. And so slavery kind of goes on unimpeded under the Mahdist state. But in 1898, the British decide that they are now in control of Egypt, and they are going to reconquer Khartoum and take back Sudan. They do so, and that is finished in 1899. And then Sudan becomes, and this is a wonderful historical phrase, the “Anglo-Egyptian Condominium,” which is a made-up phrase that means Egypt pays the treasury for the Sudan government, which is completely run by the British. So it's double colonialism. Now the British have Egypt and Sudan, and the Sudan government—that is, the British government—lasts from 1899 until basically independence in 1956 for Sudan.

The Egyptians still have great historical and cultural links in Sudan. They have often been teachers. Universities are built in Khartoum. The Gordon College is built there. There are many Egyptians involved in that. There are Egyptian who are training Sudanese soldiers for the Sudan government armies. But after 1925, when the head of the Sudanese army, a British officer, is killed in Cairo, the British work very hard to keep the Egyptians out of any kind of administration of Sudan, and at the same time as that is going on, the British are working to separate the north from the South. So there are all kinds of important ties, culturally, educationally, politically, that are created between the British and actually former Mahdists in the north, in Khartoum. They create schools, they educate the elites, the children of some of these leaders. But the British don't want to anger these communities by challenging slavery, and they don't want to keep slavery going in the south, so that pretty much segregate the north from the south. By 1930, this is pretty much in effect, and so in the south, education is pretty much left to missionaries, and the north is moving, keeping up at a pace, and people are starting to send their kids to London. So you have a terrible bifurcation in terms of opportunities, in terms of education, in terms of political involvement. People in the north are getting involved, and people in the south aren’t.

Then independence occurs. Egypt becomes independent in 1952, and we have the rise of the free officers and Gamel Abdel Nasser. The Sudanese—some have great nationalist ambitions. Others don't. So when in 1956, Sudan becomes independent and the British leave, you have northern Sudanese politicians with very little if any experience in the south, and you have a southern Sudan with very little experience in the north. So right there, you have a country that does not necessarily make sense to the people who are supposed to be its citizens, and this is why war breaks out very soon in the 50s, and that ends in the 60s. There is a peace that goes from about 1962 to 72. War breaks out again. There are peace treaties. And in 1983, war breaks out again, and the war from 1983 lasted until very recently when there was the peace treaty between the north and south.

There are many, many scholars, and many Sudanese who are quite sure that the ultimate result of this peace treaty we will be that the South will secede. And even if that is resolved, you have Darfur, which was not included in any of these treaties. So it is as if capital can't quite reach, can't keep a hold in people's imaginations, certainly hasn't been able to military defeat them. You have a country that has never really been concretized in terms of nationalism. There has never been something that held it altogether.

B.E: During the British occupation, 1885-1956, what was going on with slavery?

E.T.P.: Okay, well the British abolitionists had been the great force behind abolition in Egypt and Sudan from the 1850s, 60s, on into the 20th century. So the Anti-Slavery Society in London had been getting information about Sudan from General Gordon, who as I just mentioned, who was killed in Khartoum in 1884, from Livingston, Speke, Grant—all the great explorers of Central Africa and the Nile Valley are sending all sorts of information about what is going on with slave caravans. Much of the information we have about how slaves were sold comes from these British explorers, who are coming back to London and speaking before the Anti-Slavery Society and the Royal Geographic Society, so there’s this great link between exploration and abolition. So when the British finally take over Sudan in 1899, one would think that abolition would become a very important part of the colonial administration they were trying to set up, and it was not. There were many fears among Kitchener, and then Wingate—these were the leaders of the early Sudan governments—that if you freed all the slaves, you would have vagabonds and prostitutes running around Khartoum disrupting general civic order. And they are bringing with them their own ideas about African sexuality, about African criminality. They are not non-racist. Let's put it that way. And also, they are very afraid of disrupting the very tender treaties they have with the Mahdi’s son, or the other important Sufi leaders who had been part of the Mahdiya, who had owned slaves right and left. So they are very careful about this, and they don't really abolish slavery.

And yet, they give lip service to it by trying to keep the Northerners out of the south, because they assume that Northerners can't do anything but enslave Southerners, and so that goes into segregating the north and south, but they don't really do that much about abolishing slavery.

B.E: Fascinating. To what extent is it true that the south represents in the minds of the north, essentially just a source of slaves?

E.T.P.: In the 19th century, perhaps even earlier, the racial gradient that I spoke about earlier in terms of who could be enslaved and what kinds of people would make slaves and stuff like that, there is the language of the jallaba, and these are the slave raiders, who called different tribes in this Muslim places by different things, and so if you were a Dinka, you could be this kind of slave, and if you were an Arab Sudanese… Even the word Sudanese, Sudani, was in the 19th century a word that did not apply to the Arab tribes of the north, but apply to African tribes of the South, or non-Muslim tribes in Darfur. So these terms, as they took hold, meant that many in the north saw people from the South, or non-Muslims, with the terminology of slavery. So abid becomes a word to describe a black. Let me just stop here and say that it's very complicated. For an outsider to go to Sudan and look at the people of the north, and we think that these people in the north do not see themselves as black Africans. This is for us often quite mind-boggling. But people see themselves differently, and it is important to honor that.

I have been trying throughout what I’m saying to avoid any kind of Arab versus African terminology, because there has been all kinds of mixing over the years. Of course, if you have domestic slaves who are having children with the masters, you are going to have racial mixing. But I do think that the cultural legacy of slavery in the north has been to look at people they see as Africans as slaves or descendents of slaves, in a pejorative, and very sad sense.

B.E: So do people in the north, no matter how black they may appear, think of themselves as "Arab"?

E.T.P.: I think so. Yes. That doesn't mean they see themselves as Arabs like the Iraqis, or Arabs like Syrians, but yes, I do think they see themselves as Arabs. But they do own the term Sudanese now. That no longer just means people in the South. 150 years later, people own that term. But yes, I would say that there are many people in the north who identify themselves as Arab. You know, it just occurred to me that the one place where you might be able to find self-proclaimed African music that comes from slavery is in the music of zar rituals are bori rituals. I know that in Tunisia in the early 19th century, a Muslim jurist, Ahmad al-Timbuktawi really denounced black slaves in Tunis as being infidels in many ways, because they had brought in all these African influences. And these were communities that celebrated bori rituals, which was the kind of dance. And they have their own temples even, and music was something the apparently was quite widespread in Tunisia in households. You also have bori in Sudan. You have these kind of dance. Now, I don't know who has recorded any of this music, but that was something that definitely his store we has been considered something that slaves did.

In terms of zar, zar gets all the way up to Alexandria, in sort of these tracks rituals among women. Men are not allowed in. And the people who are the organizers of this for all Sudanese slave women. They were famous for this. And there are songs that come out of this, but because these were done among women, they are hard to penetrate, although you still have that going on now.

B.E: I have a CD of zar rituals going on in Yemen. The Yemen Tihama, or Red Sea coast. The songs are sometimes performed accompanied by a lyre, rather like the Ethiopian or Eritrean krar.

E.T.P.: That’s interesting.

B.E: But let's back up a little. What is zar?

E.T.P.: Zar is a calling up of spirits among women. I don't think that men participate in this. So among women, calling up of spirits, often to protect a child, to honor different prayers, or if someone is having a hard time having a baby or conceiving. These are crises that would concern women in particular ways, and so you would bring someone in who would summon up different spirits, different ancestors, and I know from some of my work that in northern Sudan, where you also have a great deal of zar ceremonies, the actual moments of enslavement, and raids, would be played out. This is spiritual possession. Someone gets possessed, and then speaks in the language of different spirits that are part of the drama that becomes this particular ceremony. I have never been to a zar ceremony myself. Hopefully that day will come. But I know there is a great deal of discussion about slavery involved.

B.E: I guess it's really not so surprising that we would find this in Yemen, just across the Red Sea. Someone I spoke with mentioned that water, like the Red Sea, is often a more efficient means of transmitting culture than land. But let's move on now to talk about a very specialized form of slavery, and one has been much exploited by popularizers. I'm talking about eunuchs and concubines.

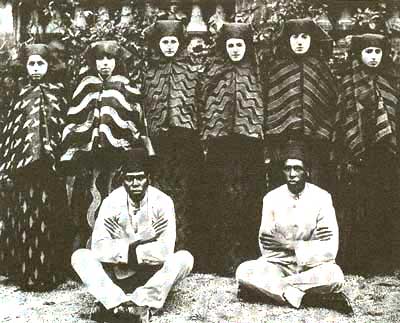

Eunuchs and concubines of an Ottoman sultuan, 1929

E.T.P.: Okay, on this one, I really won’t call it the Arab slave trade. Because as I have already said, a lot of what we're talking about has to do with Ottomans too, and they were not Arabs in any sense of the word. So I'm going to go ahead and call it Islamic slavery, for want of a better word, the slavery that the Islamic territories created. Eunuchs and concubines conjure up for Westerners all sorts of fantasies. God knows how many films and how much good harem pornography have come out with the idea of men who have been gelded, if you will, and women who are the sexual slaves of these very envied Oriental despots. But yes, there were concubines. Within Islam, it was possible for slave owners to have as many concubines as they could afford. You could only have up to four wives, if you could treat them equally, but you could have as many concubines as you wanted, and this was certainly a position that many Circassian slave women found themselves in, and also one that many Sudanese an Ethiopian women found themselves in as well. And really, this meant that they were part of the household. They cleaned, they cooked, and they did all that stuff. But also, they could be sexual partners of the masters, and if they were concubines, usually, their children could be free, would be recognized by the honor in many cases. In some cases, not.

The eunuchs were also a reality of the slave trade in the Nile Valley, and certainly in the Ottoman Empire. These were boys taken from particular regions and then brought to, and now I'm speaking only of the Nile Valley, brought to Assiout in Upper Egypt, where they underwent this operation, usually by particular people in Assiout. History and the archives show them to have been Coptic families, and I'm not sure why that is, who would do the operation and remove the testicles of these boys, and then try to heal them in certain ways. The mortality rate was high, which meant that those who survived were very valued and very expensive, and so eunuchs you really only find in Egypt in the upper, upper most echelons of Egyptian society, those closest say to Muhamed Ali or his sons and grandsons who inherited his throne, or in the Ottoman Empire. Some were brought to the Sultana in Istanbul. There were also eunuchs who came from Circassia or the Balkans, so you would also have white eunuchs. In this case I'm not sure where the operations would take place.

But they were quite valued, and because they were quite valued, they had very prominent positions in whatever family they were sold in to, or if they were part of the government in the Ottoman Empire. There is a very famous eunuch who lived in the household of Huda Sha'rawi, who was the leader of the Egyptian women's movement in the early 20th century, and she wrote these wonderful memoirs about her life, and this particular eunuch, Lala Agha, as she called him, had tremendous all authority over her life while she was growing up. I mean, it was the job of the eunuchs in many ways to oversee the education of their owner’s children. And this eunuch was particularly prized for his intelligence, and Huda Sha'rawi, a very famous figure herself, speaks with great love and also great sadness about the hold that this man had over her in terms of how he prized her and tried to comfort her when she was forced into marriage at a very early age, and also limited her education because she was a girl. So they are a very interesting group of people, and it would be wonderful the find memoirs written by some. That I have not yet been able to do.

B.E: Their high value is also based on fact they could be trusted around women, in particular, the sultans daughters and concubines, right?

E.T.P.: That's right. Although, it is widely documented that many eunuchs were married. They were not asexual people. They just couldn't reproduce.

B.E: There are horrifying descriptions in the accounts that you and John Hunwick pulled together of these operations taking place in the desert. And in some of those descriptions, not only the testicles but the entire genitalia are removed.

E.T.P.: In some cases, but in many of the other case that I've looked at in archives, that is not so.

B.E: I guess I'm wondering if there was some evolution over time in terms of people learning how this operation could be done with a higher survival rate.

E.T.P.: I truly don't know. I am certain that it was different in different places. I would imagine that in Istanbul, for instance, in the Ottoman Empire, eunuchs were not fully castrated, but I can't say with certainty. It would be an interesting question to follow up along with female genital mutilation, and how practices of that have either changed or not changed. FGM, of course, has nothing to do with slavery.

B.E: But Islam definitely does condemn castration, does it not?

E.T.P.: Yes. Which would be why you would have non-Muslims doing the operation. That would explain why you have the Copts doing it rather than Muslims. Because the Koran forbids castration. But you know, this is really a whole different topic. This really

B.E: I imagine that concubines from certain areas were favored because of their physical characteristics, right?

E.T.P.: And how well they worked. So there were ideas that habashiyat, which is the Arabic word for Ethiopian women, were beautiful, almost as beautiful as Circassian women, but couldn't really work. They were sort of household divas, whereas southern Sudanese women could work, the jediyas of the southern Sudan could really work. They were not as prized for their beauty as much as they were for their ability to work. So the Circassian women were noted for their abilities to sing, or dance, but not for work. So all this is part of the gradation.

B.E: What are your sources for stuff like that? Who wrote about these things?

E.T.P.: Well, you find it in a lot of the descriptions of households that people themselves tell. You find it in the archives taken from the slavery manumission bureaus.

B.E: Let's talk about slave religion, and the extent to which slaves really did convert to Islam. There's a suggestion that the conversion was sometimes the performance, exaggerated by particularly ardent praying and so on, but that this was sometimes a cover for other, older religious practices that slaves practiced in secret. What can we say about that?

E.T.P.: I will have to base my answer on how deeply slaves converted to Islam in two ways. One is who will they be telling their spiritual beliefs to? And that is important, because if they had been freed and redeemed by, say, Italian Catholic missionaries, often their story would be that, no, they didn't really convert. I think, though, there are many examples, and if you look at communities of former slaves in Khartoum, which Ahmad Alawad Sikainga talks about in his book, Slaves into Workers, you can see that there were actually former slaves who really were Muslims, who really did adopt the faith of their master and become Muslim. But the whole idea of conversion is very interesting, particularly in the 19th century, because of what starts happening in the 1870s and 1880s is that you have missionaries coming into Sudan, for instance, who are hoping to free slaves. These are Christian missionaries, who are hoping to free slaves, and there are many, many examples of them actually buying slaves, retaining them, converting them to Christianity, and sending them to Italy to learn Italian, and also Cairo to learn Arabic, so they would be the best missionaries around. This was very much a part of the philosophy created by Daniele Comboni, who was one of the most famous Catholic missionaries in Sudan, and who died in 1881 in Kordofan.

So, having slaves testify to their own religious experience under the rubric of the Camboni brothers meant in many ways that slaves were talking about converting to Christianity as a way out of the confines of Islamic slavery, the confines of Islam as the Camboni brothers saw it. And on their road towards freedom, their adopting of Christ as their Lord is a very big part of their becoming real people, free people who owned themselves. But those slaves who could not speak like that, those slaves who remained in Muslim households really, I think there are many examples of the fact that you could not really join society unless you were Muslim. So you do have many, many, many stories and cases of say Dinka people who convert to Islam and use their sense of Islamic faith to make the case that they should be more of a part of Sudanese society.

I will give you an example. Ali Abd al-Latif, who was the founder of the White Flight League around 1922, 23, in Khartoum, was a Dinka who had been actually educated in the north. I believe his parents were slaves. I don't think he was. And it was horrifying to some of the old Mahdist leaders to see a Dinka, championing this idea of Sudanese nationalism. He was very much a nationalist, but he was also very much a Muslim, and asserted his Muslim identity as what made him a legitimate spokesperson for Sudanese nationalism. I would say that's a very interesting and very complicated question. Because how religious authority looks to have slaves speak, certainly in Christianity, what it means to have a former slaves say, "I was a slave, but now I'm free, and the reason I'm free, or part of why I’m free, is that I have been saved,” versus, "I want to be a big part of the society and I am a Muslim, and my conversion not only was complete, but my family's conversion was complete." So I think there were many, many people who actually did convert.

And there is a gender difference too. Often, there were certain things that women took care of themselves, and that's when you get into zar. There's not much that is Islamic about zar. This goes back way, way back to other practices among women, and it was often the case that women were not Muslims. Women were necessarily educated in terms of what was proper, Orthodox Islam. This was something that was fought for in Sudan around the turn-of-the-century, to actually get women to have a stronger sense of Islamic practices and things like that.

But let us also not forget that within Islamic slavery, slaves have the right to appeal to an Islamic judge if they're being mistreated. So if you are a Muslim slave, and you go to the Shari’a court, as many did and certainly did in Egypt as well, and use say, "I need help, and here's what happened." Well, if you were not a Muslim, you wouldn't have that. Let's face it. The Christian missionaries were not everywhere. And so there were partially many avenues for help that Muslim slaves could find.

B.E: Interesting. Also, I would imagine that even if the parents’ conversion had an element of the performance to it, the free children of those parents growing up in a Muslim society might be more devout.

E.T.P.: That's also possible. That's right.

B.E: So, coming back to music, we have said that overt references to slave history are pretty rare, even in Sudan and Egypt. But I'm still curious about the evocation of Nubia, which I think has to be seen as an assertion of Africanness in an Arabized context. One popular singer and Egypt who has donned the cloak of Nubia is Mohammed Mounir.

E.T.P.: I'm a very Cairo centered scholar, and the Nubians that I know in Cairo are very, very protective of their identity, and are very proud of it. And in terms of marketing it, I think someone like Mohammed Mounir has tried very hard to market himself with great respect for the culture that he comes from, but I think what makes him important to Egyptians is that he sees himself within an Egyptian context. He is a movie star, and a theater star, in addition to being a wonderful musician. He's in all kinds of wonderful movies and he gets prizes. But he is speaking in these movies and colloquial, Egyptian dialect. He is very much a part of an integrated, Nubian community. He is an Egyptian, as well as he is a Nubian.

Now, the other Nubians I know, who are shopkeepers and such, tend to see themselves also as very much part of the Egyptian scene, although they make a lot of differences in terms of not being like the other Egyptians. They are not trying necessarily to integrate themselves culturally. They are very protective of their own language, and some look at Mohammed Mounir. I think they admire him and are concerned in some ways that, like I said about Youssou N’Dour, that he has become very much an Egyptian, not so representative of Nubia. Look, there's not as big a market among Nubians. They are a much smaller community. But I don't know that has happened in other ways, and the other thing that I would say, and perhaps I'm completely wrong here, is that Mohammed Mounir looks like he could be from any place in Egypt. He is not dark skinned in the sense that some of the other Nubians that I know are. And so he has been able, perhaps, to capture Egyptians’ imagination because he blends. He blends beautifully, and gracefully, in ways that perhaps other Nubians do not.

B.E: So it would be natural that Nubians would be sensitive about how their identity is projected into the mainstream. They might have mixed feelings about who does that, and how they do it.

E.T.P.: I will give you a little cultural history about Egypt in the period I was talking about earlier, in the late 19th century, particularly when they lose the colony in Sudan and are colonized by the British. This is an incredible period in Egypt. This is called the Nahda, or “renaissance,” and there is so much flowering in terms of literature and plays, music and poetry. All kinds of newspapers are created, and satiric journals, and it's just marvelous. In the late 19th century, or certainly by the turn-of-the-century and during World War I, there is this guy named ‘Ali al-Kassar, who is a very famous Egyptian actor who performs in the new theater district in Ezbekiya Gardens as Osman ‘Abd al-Basit, “the one and only Nubian." And he takes on the character of this Nubian man, who is usually a servant, who because of this status becomes sort of the confidant of welfare Egyptians. He is the heart and soul of Egypt, but he is Nubian. This is performed in blackface, and ‘Ali al-Kassar, although many more sophisticated artists look at him as the worst kind of vaudeville and the worst kind of slapstick, is part of a tradition in Egyptian, and also Ottoman culture, of impersonating others.

There was another actor called Najib al-Rihani who had this great character called Kish Kish Bey who was from the Upper Egypt, or the Sa’id, who is famous in Cairo for his goofiness, and sort of takes on in a comedic way lower Egyptian stereotypes, or Cariean and Alexandrian stereotypes of the country bumpkin.. The wealthy country bumpkin. But anyway, you have‘Ali al-Kassar adopting this Nubian identity, and this goes from 1916 to his death in the ‘50s. I guess he dies around ‘55 or ‘56. There are movies of him being this Nubian character. So there is a lot of suspicion, rightly so, among Nubians today, who say, "Wait a second. Our identity has been usurped by people who are not Nubians.” And it's funny. Because there is one movie of ‘Ali al-Kassar’s that's called Seven O'clock, in which he is not in blackface. He is playing Osman ‘Abd al-Basit, this Nubian character, who is very, very popular, by the way. And the way you know he is Nubian is they go to Aswan, and they actually have Nubian performers come out and sort of dance around him, to say that he is a real Nubian. So they are used sort of as markers of his identity, because by that time, they were not doing the blackface onscreen. It is very interesting. And then you have actual Nubian performers, but they are folkloric. They are sort of the furniture in the room that declares the identity of the owner of the room.

B.E: I guess I was seen as more tasteful. But the character is a servant, not a slave.

E.T.P.: Not a slave. Right. And the character is constantly asserting himself as half-Nubian, half-Sudanese. I have a whole chapter on this in my book (A Different Shade of Colonialism). There is an amazing history about how this identity is used by a very nationalistic, Egyptian performer who is extremely popular. This is in some ways gutter comedy, but it played to a larger crowds than other things. It's interesting because the music that is performed situates them. It is a map, a marker. The Nubian performers themselves are not really identified.

B.E: How does slavery wane and, to the extent that it has, end in Egypt and Sudan?

E.T.P.: With the increased attention of British abolitionists and Italian missionaries from pretty much—I would say that the French and Italians are involved in this by the 1840s, and the British somewhat later—there is a movement that creates an end to the slave trade in 1874. People are given a seven-year grace period. The purchase of slaves, not the owning of slaves, but the purchase of slaves in the Nile Valley is rendered illegal. And the Egyptian ruler at this time is Sa’id Pasha, and then ‘Abbas Pasha, and then his successor, Khedive Isma’il. Sa’id Pasha really is the leader of Egypt in 1874 when this happens, and so the purchase of slaves becomes illegal, although Isma’il has lots of slaves, and a lot of people have lots of slaves still, you can no longer buy them. And so this creates a real pressure in Egyptian society, and there are trials of wealthy Egyptian nationalists who the British are just looking to get for owning slaves and purchasing slaves. But this really pushes the slave market underground, and what the British do, even before they have occupied, because Egypt goes bankrupt in 1876 and so the British and French authorities take over the Egyptian treasury. So a couple of years before Egypt is actually occupied by the British, there are Europeans in great positions of power in Egypt who are thorns in the side of the Egyptian Khedive, the Egyptian ruler.

Because of this influence, the British are able to create manumission bureaus, or slavery bureaus all over the Nile Valley, in which slaves are encouraged to come and get their papers of manumission. And some do. By 1882, when the British come in take over Egypt, they are in a position to police this. They are not in a position to do this in Sudan, because Sudan belongs to the Mahdi at this point. They can't get in. And so you have, and to this is what I'm working on now, families in Egypt whose whole sense of the household is changing because they are not going to be able to buy more slaves, and also because there has been an internal debate within Egypt about: why do we have slaves?

There were important Egyptian thinkers who really challenged the elite’s view of slavery. One of the most famous and one of the most interesting is this wonderful journalist named Abdallah al-Nadim, who really felt that Egyptians should just stop slavery. Enough is enough. That it had terrible implications for women in their own households, that it was a dissolution of the Egyptian family, and that it did no service whatsoever to slaves. In his newspaper called al-Ustadh, al-Nadim has a beautiful article, published in I believe 1892, which is a script between two, former Sudanese slaves who are talking about what it means to be free. The article is written as a script because al-Nadim knew that people read them out loud in coffee houses, and this meant that Egyptians would have to actually act out the identities of former slaves. He's really something, really a genius, and it's all about, “No we don't become mature. We were rendered perpetual children." It's quite lovely and quite graceful.

So slavery begins to die out in Egypt because there is social pressure, and because it no longer makes sense, and I would say by the early 1900s, it's pretty much done. You still have people who are former slaves living in households, but it is pretty much done. In the Sudan it is more complicated than that, because as I talked about earlier, the Sudanese government, run by the British, was much more ambivalent about what to do with former slave communities. So they were not ready to say, "Slavery is abolished." In Sudan, this is one of those great hypocrisies of British imperialism. Those same people who had been calling for abolition in Egypt, really saying that Egyptians did not deserve to govern themselves because they still had slavery, well, once they come in and to take over the Sudan, they do not free the slaves.

You can read about Sudanese slave owners themselves freeing their slaves in the 1920s and 1930s, and I'm not sure if it's ever completely wiped out that point, but it is certainly considered anathema by the thirties and forties and fifties and sixties and seventies. However, there are many, many claims that slavery has been reintroduced because of the long, long civil war in both the South, and in Darfur. I would say the first real scandal of the reintroduction of slavery is brought to public attention in Sudan but to Sudanese scholars, Suleiman Baldo and Ushari Mahmoud, who actually go to a place where there has been a great massacre of Dinka, and document slavery right there. They did this in 1987. One was imprisoned for this, and the other one is living in the United States now. Because it is very dangerous. It is still very controversial. But there are so many cases now that have come to the attention of the Red Cross, Christian Solidarity International, not to mention Sudanese organizations who are really operating underground, that slavery has come back. I think it is fair to say that it is not gone from Sudan at this time.

B.E: And there have been famous journalistic accounts, in particular those two reporters from the Baltimore Sun.

E.T.P.: Right.

B.E: This is very interesting. It's not a matter of slavery having not disappeared in Sudan. But that it has been reintroduced. That makes you wonder whether it really ever completely disappeared. And of course, the other place often cited as still having slavery is Mauritania.

E.T.P.: In Mauritania, it has not disappeared. But that’s a whole other story. I’m not even going to go there, because it's huge, and it's different, and I think we have to be careful about assuming that all these places have the same kind of history. Mauritania is really a different slave population, different relationships with the slaves, the fact that it is still going on. It has different countries influencing the abolition movement, and different cultural influences going on in that sense. I wouldn't even begin to compare. But in Sudan, whether or not it stopped, I really can't say. I truly don't know, and as a historian, if I don't see it in front of me, I'm not going to say that I think it happened in Sudan. But it's definitely back. And how do you document it? This is part of the problem. How do you actually document it? This goes back to how does someone say, "I was a slave”? So there's this real need for people to become their own archivists in a sense, and for organizations to look for slaves to proclaim themselves slaves. It's a sad history of slavery in the Nile Valley. The fact that it is so controversial to even talk about it shows that is not dead at all.

B.E: I think there are some key ideas that need to emerge out of this program. One is how much more complex this subject is than any simple model we would try to impose on it. Just the idea that Mauritania, so often lumped together with Sudan and this discussion, is a completely different narrative, and that it is dangerous and misleading and wrong to impose a foreign model there. Maybe you could address that directly. Why can't we do not see Arab Islamic slavery in Africa has one subject?

E.T.P.: Simply put, the reason we cannot see African Arab slavery as one subject is because we don't look at African slavery as one subject. British slavery in the Caribbean was not the same as American slavery in the United States South. French slavery in the Caribbean was not the same as British slavery in the Caribbean. We don't do that. Our historiography is very careful about keeping regionally specific Western African slavery. Well we need to do the same thing when we are looking at the equally vast territories where there were African slaves in Islamic lands. Istanbul could not be more different from the Jermina, and Khartoum is very different from Fes, and Cairo is not the same as Damascus. These are vastly different places with their own kinds of cultural, economic, and political systems and why would we dare assume that just because it's Islamic, it would be the same thing, or just because it's African it would be the same thing. I think that's carelessness on our parts if we indulge ourselves that way, and it means that were trying to take a complex story and make it too simple. It's not simple. Slavery is never simple.

B.E: I like the passion. [LAUGHTER] The other thing that has to emerge in our program, and I asked this question in terms of music before, has to do with scholarship and literature. Ther is this ever growing narrative about the Western, Atlantic slave trade. I recently read that so far this year, 75 books have been published about slavery in English. Just this year. And that on top of countless other books, films, television documentaries. This is a huge subject that is being discussed very openly. I don’t think that’s so much the case in Islamic contexts today. There is not the same level of reflection and discourse. Why is that?

E.T.P.: The reason my slavery is not discussed with the same attention, volume, the same passion in the Islamic Middle East as it is in, say, the United States, there are several reasons for this. One, as in the case of Sudan, it is still going on, and this makes it very difficult for the Sudanese government, so it becomes a huge political controversy. It is very dangerous for people to talk about. If they talk about it, they're often imprisoned. You cannot get into do research about this anymore. That's one thing. It is politically dangerous in places where it still exists. But there's another reason to, which is that, especially after September 11, the Western world, if I can bifurcate the globe in the sense, the Western world is really angry with the Islamic world, and very suspicious of it. This has created a great deal of anti-Islamic, I would call it racism. And so, there are many people who fear that if you explore the subject, you are catering to the worst kind of Muslim bashing. This age-old idea that Muslims are all despots, and they can't really govern, and they don't know the difference between politics and slavery.

And also, you have the very controversial question of Israel. Much of the scholarship that has developed about the Islamic slave trade, especially in the 1970s, was sort of an example of, "Look, if they could be this way to Africans, well look with a do to Jews." We saw an oversimplification of the issue by cloaking it in terms of the United States civil rights movement. Again, this is an imposition of one history onto another history, which grossly oversimplifies the history of the Islamic world of slavery. It means we don't really learn about it. We just make ourselves look better by comparison. So I think that's a very important part of why it hasn't been discussed, certainly among communities of Middle East scholars. They are concerned about the image of the Islamic world in the West. I myself feel very sensitive to that as a scholar, which is why I would like to be as accurate and as broad as I can, and as specific as I can when I discuss slavery.

However, I do think it is important to hear the slaves themselves, to see what they say. If we think about slaves as some of the greatest explorers in the world. The fact that they crossed borders no one else crossed, that they crossed borders in ways no one else crossed. They had to learn to translate cultures in ways that say David Livingston would have prayed he had the same kind of skills. If we look at slaves in and of themselves, as some of the most powerful interpreters of culture, I think we can tell a different kind of story, one which really honestly tells the history is slavery, but also empowers slaves themselves, in the simplest humanitarian ways.

B.E: That is powerful. Isn't it true that one of the reasons we have this highly developed narrative about Atlantic slavery is that we do have powerful accounts from slaves, telling their stories. Have these narratives forced us to reckon with history? Also, isn’t there something about the kinds of communities that freed slaves lived in the Americas that's very different from some of these Islamic contexts? The freed slave living in Istanbul, Cairo, or the Gulf is now being embraced and integrating into a society in a very different way from blacks and reconstruction America. They themselves may be less motivated to tell their stories and to bring their own narrative to light. It seems to me that the freed slave in the Middle East might be less motivated to bring their story to light, and that may be part of the silence we live with today.

E.T.P.: Well, first of all, I think that the history of narratives, and slave narratives, is really complicated. Even in the West, it is really, really complicated. Remember, William Lloyd Garrison told Frederick Douglass what he wanted him to say. And Frederick Douglass said, "I'm going to say it this way." And that was very controversial. And then you also have the WPA interviews with slaves that were usually, with the exception of some like Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes, most of the interviewers of the former slaves were actually white. So you always have had a sort of framing problem. Who was actually telling the story? And then there were people who actually told their own story, like Harriet Jacobs, and people believed for decades, if not a century, that it was a white woman who wrote the story. Because it was difficult for Harriet Jacobs to actually get published under her own name. So I would deny that slave narratives only come from African-Americans wanting to tell their story. That comes much later. That's because of the civil rights movement, that there is a growing class of intellectuals, black intellectuals who are able to get the story told, but they are also breaking through some of the framing of slave narratives in American history.

Now going to the Middle East, where you haven't had that kind of movement, it's different. As you very rightly said, there is not the same kind of self-segregating or self-identifying communities of former slaves in one place. I mean, look, it is harder to grasp onto that kind of culture. But there are narratives. It is important to go to the narratives and see, for instance what slaves said to the courts, how they presented themselves to the courts, and there is a wonderful work being done about that. The book I'm trying to work on now is memories of slaves in the Nile Valley. And I'm looking at slave holders and slaves, and how they remembered it, and how it’s published, and how the stories are actually told, but published too. That's very important, that they are published. But those narratives are either done under the auspices of Christian missionary society, or within a court system. And now you have—and this has brought still more attention to Sudan—people like Francis Bock and Simon Deng coming out and saying, "I was a slave five years ago. I was a slave 10 years ago." And these books are coming-out now, 2005, 2006.

But yes, it is very different. And the fact that you actually have published slave narratives coming out now, and they are published not in Arabic, but in English, and I think that has a lot to do with great sensitivities to it, and great fears about Western scrutiny. Let me just add one thing. Abolition came to the Middle East on the heels of the colonizers. All those figures who were calling for the abolition of slavery became imperial, colonial administrators in Egypt. So abolition always smelled of imperialism, and that is part of the story the think it is important to mention. It never looked like it was simply humanitarian. It always looked like it was part of the carving up of Africa for European interests.

B.E: Wow, this is a lot. I’m in awe. But also, I am left with the sense that this is still a young area scholarship. There's a lot more to do, isn’t there?

E.T.P.: Yes. Yes.

B.E: Thank you, Eve. You have taught me, and our listeners, so much.

E.T.P.: Thank you.