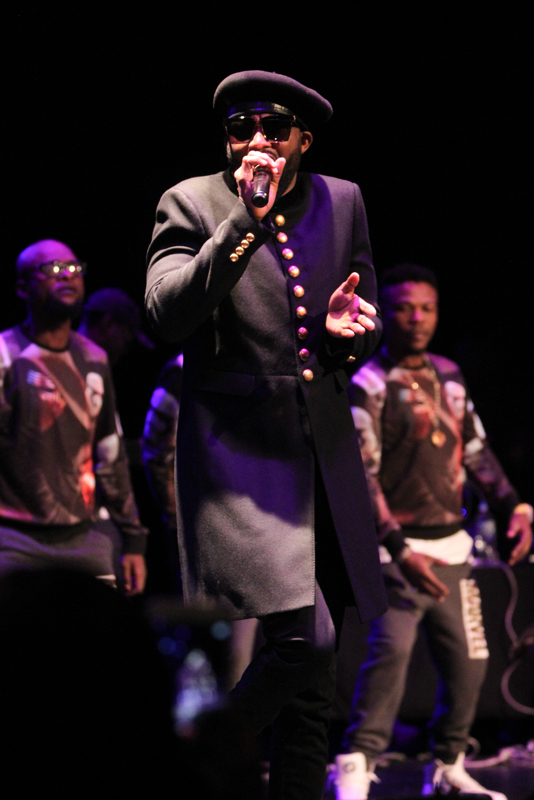

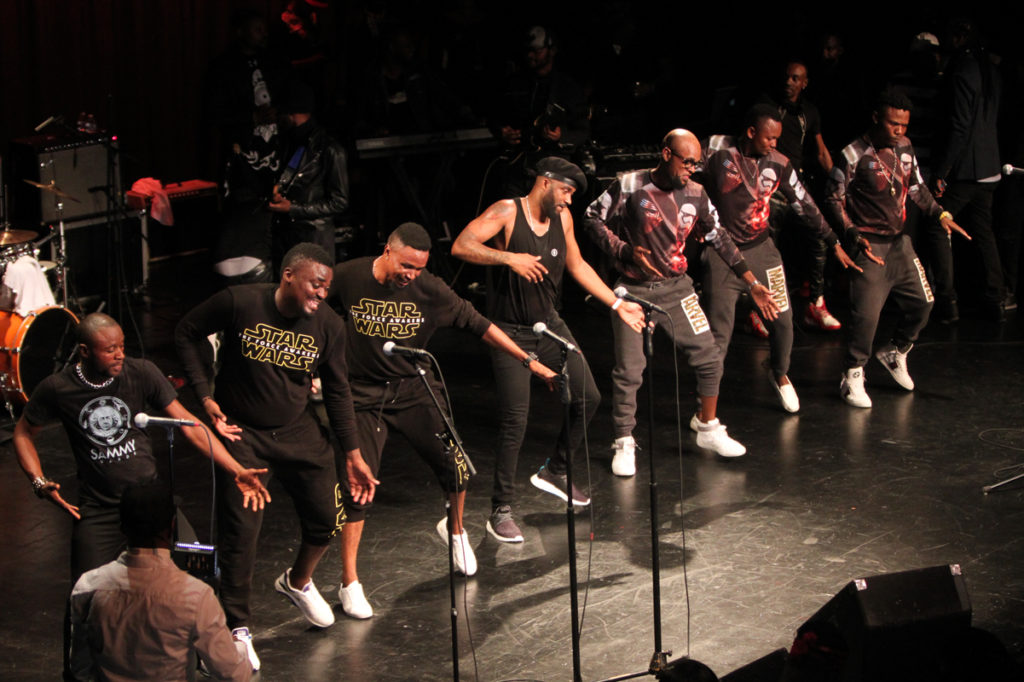

On Nov. 4, the Afropop team interviewed Fally Ipupa, one of the best-known singers and bandleaders in Congolese popular music, in his room at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel. Fally and his group F'Victeam performed live the next night, at New York's Symphony Space. If you would prefer to read this in the original French, click here. Photos by Sebastian Bouknight.

Morgan Greenstreet: You are known by a few different stage names, including “Three-Time Hustler.” Here in New York, we’re familiar with the hustle, the New York City hustle. But what was your hustle like when you were coming up as a young artist in Kinshasa, at the beginning of your career?

Fally Ipupa: It was like the hustle in New York, but it was difficult as well. We worked hard to become the well-known artists that we are today. We started in Bandal [short for Bandalungwa, a municipality of Kinshasa]. It was true hustling, because at the time there was no Internet, you had to work, and it was complicated to get on television, you had to give it your all. So, today, thanks be to God, we are doing things here in New York, in France, in Africa. We’re hustling, but Kinshasa style.

And you’re here in New York to perform with your group F’Victeam. But F’Victeam is also a record label through which you put out a recent album, Libre Parcours, which features members of your group. It seems rare and special to me in the history of Congolese popular music that you give so much space to show off your group, to give them their own creative space. How did you come to this idea?

Yeah, that’s important. You known, music is like sports, you need to pass the baton. One won’t be here forever; I think that at a given moment, one has to know how to push young artists, and other artists in general, one has to open doors for other talented artists. Today, sincerely, I have nothing left to prove. I make music out of passion, because music is my life. But I am not the only artist in the Congo, so it is necessary to flood the field with many Congolese artists who can sing, dance, write and compose. I think that’s the best way to promote Congolese music, to lift the flag of our Congolese music as high as possible.

Is the F’victeam label also a way of uniting the members of your group around you? Many great Congolese groups, Wenge Musica for example, were almost destroyed because so many members split off to form their own groups. Is this also a way of gathering your musicians closer to you?

No, honestly, I don’t care if people leave the group, if they go and start their lives, I don’t give a damn; that’s not even a problem. I am an artist, I make music, firstly, because, thanks to God, I have the talent. All Congolese artists are ungrateful, except me [laughs]. So, no, this isn’t even a way to keep musicians in my group! On the contrary, my musicians have the right to go do collaborations, to participate in projects, whatever. My vision is not the same as that of my elders, my peers, my brothers, no! It’s a question of sharing: I created the label in order to produce artists, not necessarily Congolese artists, or artists from Bandal or Kinshasa, but just to produce talented artists. The artists who accompany me today are talented, they produced an album that was pretty successful, even if it wasn’t a smash hit; it didn’t sell millions of copies, but that’s O.K. It has some beautiful songs, and I think it was the best way to launch the group.

Today, if one of the artists who accompany me wants to follow his path, start his solo career, I will support that with pleasure. There’s no question of retaining artists, that’s not part of my vision, in fact. My artists remain family, because most of my group, many members of my group are my childhood friends, we grew up together. There are people in the group who I’ve known since I was 10 years old. For example, my guitarist, our musical director, and others, they were with me when I started. So, firstly, it is a family clique. But if someone wants to go pursue his career, there’s no question of retaining them. But I can understand when people say that groups break up because our elders didn’t want to give younger artists a chance and all that. Even here [in the U.S.], there are always artists who leave groups, it’s normal. I wanted to create this label to propel artists, not hold them back. They’re not obliged to work with me. I have my life, my vision, my career and they are there, talented, and they accompany me. But if today they decide to make their career, it would be my pleasure to support them.

These days, you are one of the, if not the ambassador of Congolese music in the world, and throughout Africa. In the past, Congolese music was at the top of the scene, but lately it’s more Nigerian music, or Afrobeats, which includes music from other Anglophone countries. So, for you, what is the place of Congolese music in the world in general, and across Africa in particular, right now?

Yeah, firstly I’ll say that it’s a good thing that African music is on the throne. If it’s Nigerian music, or Ivorian, or South African, it’s a good thing. But Congolese music is the real deal! The music is for real! I respect Nigerian music a lot, I have many Nigerian friends, I respect their music a lot. Today, we’ve lost our place a bit, I’ll say we’re no longer number one, but we’re still hitting hard. They have the benefit of language, they speak English, and today the Afrobeats current is working very, very well. I’m really happy for them, but we are still here, because, if you put a Congolese artist on stage with a Nigerian artist, there will be a really big difference: they’ll defend their music and we’ll defend ours! I’ll take myself as an example: I’ve been on the scene for 10 years, I’ve been touring for 10 years, I have three albums out with multiple singles.

So we’re not complaining, but Congolese artists need to stop their stop with their stupid, futile arguments, they need to focus, and work hard. That’s how the Nigerians are, even if there are small problems, and don’t worry, I speak with an understanding of the situation, because I have a lot of Nigerian friends. There are always small squabbles, but at least they put intelligence into their stupid games. But yeah, it’s time for Congolese artists to respect each other. I believe that musically, we are good. Sincerely, I wouldn’t say we’re coming in last place, at least I am not among the last in any case. There will always be the Congolese side, the Lingala side, which will try challenge the other side. But we respect our brothers a lot. For me, the opening is good, if it’s a Ghanaian artist, a Nigerian, an Ivorian, as long as it stays in Africa, it’s cool with me!

[Laughs] For sure. As a foreigner, there’s one facet of Congolese music that interests me a lot, that’s libanga [shout-outs or dedications in music, often in exchange for monetary donations or other forms of material support. Listen to our recent Afropop Closeup on the subject]

Ah! Libanga! We are the precursors! Today, even Americans are starting to do dedications in their music. Even our Nigerian brothers, even in Europe…except they still don’t know how to get paid from it! We are so far in advance! One day they will…You know, 20 years ago, only Congolese musicians played live concerts, and, still, today Congolese musicians are the only ones who really play live concerts. You see, I came here with 16 musicians, guitars and all that. And we’ve been doing this for 30 years, this story of dedications, shout-outs, libanga. Go ahead, finish your question.

No, I think you’re getting to the point. I believe that, throughout the world musicians don’t really have the economic means to produce our music. Albums don’t really sell like they did in the past. So musicians everywhere need something like libanga! [Laughs] We need a system that will pay us to continue making music. I know that libanga isn’t exactly a "system" per se, but I’m interested, how does it work for you as an artist?

It works really well! You know, basically, libanga is, firstly, a way to thank someone, to recognize support, or to support someone. At the root, that’s what it is. You know, when I make a libanga, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you have paid me something; it is a sign, first and foremost, of affection. After that, of course, there are people who have tried to create a business around libanga. There are people who have become famous, who started a successful business, solely because someone shouted them out in a song, they received a real libanga from a well-known artist, and after that they also became well known, they became a star, and they created their own business. In exchange, they will always want to contribute every time the artist goes into the studio to record an album, they’ll want a new libanga.

So we made a business out of it. Of course, there are also free libanga, libanga done just to thank someone, to show gratitude to someone who has helped you. Libanga is a truly Congolese thing, and I’m proud to be a Congolese artist who has been a part of this system of dedication, of libanga, because, I’m telling you, mark my words, in five, 10 years, not only Congolese artists will be doing libanga!

O.K.! But there are people who criticize, saying that libanga gets in the way of the music.

Yes, I understand, there are artists who overdo it. You know, when I do libanga, I leave space between them. Everyone does it their own way. As for me, I don’t record an album in order to do mabanga [pl. of libanga]. Because there are artists who record in order to do mabanga. That becomes a bit complicated, you know, because there’s always a limit, otherwise you pass to the other side of…you destroy the profession. But when I record, I first record the melody, the lyrics, the music, and then I add the libanga.

Ah, O.K.! I understand.

And I try to do make them clean.

I’ve noticed you sometimes sing your libanga, you include the names in the melody of your songs.

Exactly! For example, there are songs where I don’t even do libanga. But wait, I’ll give you an example of a song where I did libanga even in the melody of the song. [Sings] "Gino Alcapone," so, you see, because I sung it, you wouldn’t even think that was a libanga, right?

Yeah, yeah! True!

So you see. But there are people who do it…what’s your name?

Morgan Greenstreet.

Morgan Greenstreet [Shouts it out] See, that kills the melody. Anyways…

[Laughs] Thanks! Last question: Right now, in the Congo, there’s a crisis of democracy, at least that’s how we see it from an international perspective. How do you see the place of artists like yourself, well known artists, what role do you play, or do you have a role to play in the democratic process in the Congo?

Sincerely, we don’t have a role to play when it comes to—how do I say this—when it comes to passing a political message, but we do have a role to play to pass a message to the population. I have always said, I’m on the side of the population. We want a country without war, without insecurity. We want a good and honorable Congo. We are obligated! We want to have this, how can I put it? We want to have real value! Today, we want to be respected as well. So politicians should do the right thing, because as you know, they’ve been juggling us. One day, you’ll see, an artist will become president! So, I always say, they need to take their responsibilities seriously, and they better not destroy the country. So yeah, that’s politics.

Thanks so much for your time!

Akornefa Akyea and Morgan Greenstreet with Fally Ipupa at the Waldorf Astoria. Photo by Anna Touré

Akornefa Akyea and Morgan Greenstreet with Fally Ipupa at the Waldorf Astoria. Photo by Anna Touré