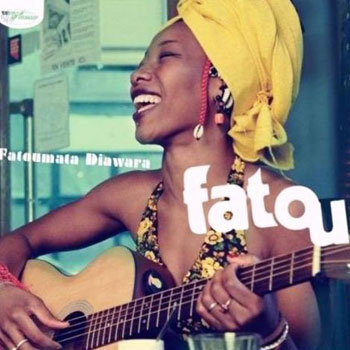

Fatoumata Diawara is having her moment. Tall, slender and beautiful, and a talented singer and songwriter, Diawara created her debut CD with the help of the team at World Circuit Records, the folks who shepherded the careers of Ali Farka Toure, Oumou Sangare, Cheikh Lo and the Buena Vista Social Club. The resulting recording, Fatou, spent 6 months atop Europe’s world music charts last year, and Diawara and her group have toured widely ever since. Now the CD appears in America just in time for her first US tour, and at a moment when many eyes are focused on Mali—now enduring a far sadder and more violent turn in the spotlight.

Diawara has been described as “headstrong,” and you sense that quality when her mellifluous voice rises to take on a ragged edge, moving from quiescent to fierce in a carefully modulated escalation of passion. As a girl, she famously escaped her parents’ restrictive grip and boarded a flight to Paris to begin a career in music, theatre and film. As a singer, she recorded and toured with her mentor Oumou Sangaré and American jazz singer Dee Dee Bridgewater, among others. All this was preamble to this recording, which, for all its good qualities, does not entirely fulfill its promise. These twelve songs broach profound subject matter with reflections on a girl’s youthful rebellion, resistance to intolerance and bullying, resistance to arranged marriage, and even condemnation of excision, the brutal practice of female genital mutilation, still common in Mali.

Diawara’s singing voice is wonderful, sometimes soft as a whisper in the manner of early Rokia Traoré—another friend and mentor—other times full and defiant, and, occasionally, showing the elegance and nuance of the great Oumou, as on the percolating anti-war song, “Kèlè.” The opening track “Kanou” has a slyly seductive hook, and the upbeat “Sowa” a more obvious but equally effective one. “Sowa” is surprisingly pop for a song about mothers forced to give up a child due to poverty, but it’s in the tradition of uplifting songs about downpressing subjects.

Elsewhere the vocal melodies are less memorable, however well delivered. Most of the songs receive gentle, understated instrumental accompaniment, typically guitars and light percussion, much of it played by Diawara herself. Toumani Diabaté insinuates subtle and masterful kora work to the waltz-like “Wililé,” a song that underscores a central message of the CD: to get ahead in Africa, a young girl must rebel against her parents. Other grooves feel a little too restrained, a little too precious, not quite up to the power of Diawara’s voice, let alone her subject matter.

Diawara’s biggest challenge is living up to her most prominent antecedents—Oumou, Rokia and also Habib Koite, a pioneer in the singer-songwriter side of Malian pop. All three of those make more savvy use of traditional music than we find here. Songs shuffle and lope amiably, aided at times by traditional instruments, but the music feels familiar, safely free of folkloric quirks or more than occasional flashes of true originality. The song with the most trenchant and visceral groove—“Mousso” in praise of women—owes its success to Nigerian Afrobeat drummer Tony Allen, whose august command of cool makes the album’s other grooves feel tepid by comparison.

Fatou—which was recorded some two years ago—arrives in the US during Mali’s darkest hour in modern history. The album’s peaceful vibe and well-meaning messages are laudable, but feel a little out of step at a time when peace-loving Malians are facing the choice of becoming warriors, or submitting to horrendous privation and abuse. YouTube clips of Diawara’s recent concerts show her to be an engaged and exhilarating presence on stage. (This clip from WOMAD is particularly good.) One hopes her next recording will kick a little harder and dig a little deeper. For clearly this is a gifted and committed artist, and a welcome new arrival in Mali’s musical pantheon.