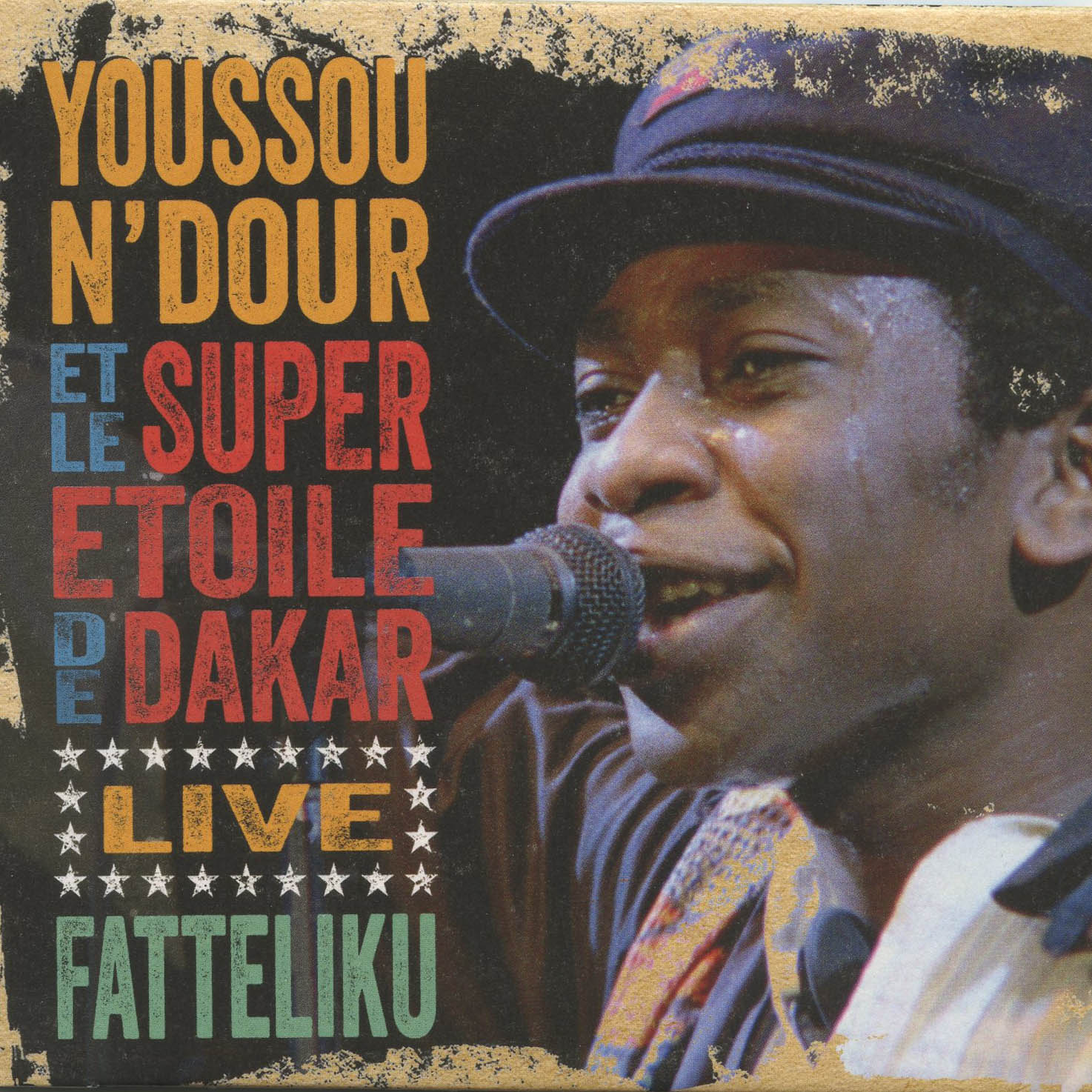

It was the stuff of history when Peter Gabriel invited Youssou N’Dour and Super Etoile de Dakar to open up for him on his 1987 tour, promoting his massively successful album, So, on which N’Dour had performed. Gabriel personally introduced N’Dour to his fans at the start of each performance, and fans liked what they heard. How could they not? N’Dour’s was one of the tightest and most interesting pop bands in West Africa at the time, and very few outside Africa had any clue about them, or about the vast world of popular music they represented.

The date of this recording—October, 1987—has personal resonance for me as I was about to embark on my first research trip to Africa, gathering material for early broadcasts of Afropop, about to launch on American public radio. So hearing these six long, leisurely tracks, performed before an enormously enthusiastic crowd in Athens, Greece, all these years on is nostalgic. It is also a useful and clarifying reminder of what made African music a viable international commodity in those days, and where it has been since.

Peter Gabriel had been listening to N’Dour since catching a live show in Paris in 1980, so he knew well what he was doing by placing a 10-piece band from Dakar in front of rock audiences. N’Dour had just turned 28 at the time. Born to a line of Tukulor griots, he had formed Le Super Etoile at 18, so the band was in a 10-year-deep pocket by this time, and it shows. The vibe is one of mastery, but also youth. Hard to imagine that this confident young crooner would go on to be named “African Musician of the 20th Century” (by Folk Roots magazine), or to spend 18 months as a minister in the Senegalese government in 2012 and 2013—but then again, why not? No one could doubt that something new and powerful was beginning here.

The five Super Etoile tracks are all in the 8-minute range, leaving time for guitar solos, crack percussion breakdowns, and vigorous call-and-response vocals between N’Dour and the audience. The recording and mix are excellent, letting us feel the crowd without being distracted by it. The set begins with “Immigres,” one of the seminal songs of international Afropop. That insistent rhythm guitar riff remains iconic, and N’Dour’s vocal fairly blooms with enthusiasm and virtuosity. Thierno Koite’s single saxophone is a mark of the band in these days, and the dual guitars of Jimmy Mbaye and Pape Ngom still dominate the sonic texture, with Habib Faye’s keyboard mostly taking a back seat. Powerful sabar and djembe percussion from Assane Thiam and Babacar Faye comes forward midway through “Immigres,” punctuated by Mbaye’s rocking guitar note bends—all sounding as fresh as they did nearly three decades ago. Then there’s the content of “Immigres,” warnings and laments about the difficulties facing Africans in diaspora—a subject that, like the music, has not aged at all.

Even harder mbalax follows with “Kocc Barma” composed with bass/keyboard phenomenon Habib Faye, who hails from a musical dynasty in Dakar. The crowd joins joyously in singing along, but do they know they are singing in praise of the 16th century Senegalese Sufi philosopher, Kocc Barma Fall? Not likely, but they can tell that this music runs deep. There’s a third real mbalax number here, the jazz-inflected “Ndobine,” near the end of the set. Elsewhere the grooves are less gnarly, easier for non-African ears to grasp—all part of N’Dour’s skillful seduction.

“Nelson Mandela” projects a strong 4/4 beat, and offers universally understood vocal refrains—“Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe...Nelson Mandela” and “So-weeeeh-TO!” This one was sure to rouse a live audience in the dramatic final years of South African apartheid, though, inevitably, the track feels more bound to its time than others. “Sama Dom/My Daughter,” with its rock/reggae groove and English lyrics, also makes for friendly fare. Its refrain—“Know your destiny; do not follow your heart”—offers an intriguing introduction to Senegalese Muslim philosophy with words that may have provoked questions among rockers raised very much on a DO follow your heart ethic. The album closes with N’Dour and his two percussionists joining Gabriel’s band adding fire and spice to his chugging rock anthem “In Your Eyes.” N’Dour’s searing, sailing high notes sound as good here as on the consequential studio version of this song on So.

It’s worth noting that this moment of connection and discovery led to significant changes in N’Dour’s music. On subsequent albums, he toned down the angular rhythms of mbalax and donned trappings of progressive art rock. He took some heat for that from critics and longtime fans. But it’s also worth noting that N’Dour’s music, and mbalax itself, were never about any sort of purity. They were always hybrid forms, open to absorbing new influences, whether Afro-Cuban music, griot tradition, r&b, rock, jazz, reggae, or, famously, the art music of Egypt. And of course, the hybridization of West African music has continued apace. What this recording makes clear is that the 1980s was a sweet spot in that process, a point when the connection to African tradition was robust and palpable, and the open-armed embrace of international trends warmly inviting. No band better captures that moment than N’Dour’s. Kudos to Gabriel and RealWorld for at last sharing this crucial performance.

More on Youssou N'Dour: From Best of The Beat, interviews from 1987 and 1994.