In February, 2006, up-and-coming Congolese singer and bandleader Felix Wazekwa came to the United States for the first time to do a limited, introductory tour in Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York, including an unusual stop at Harvard University as part of a symposium on Congolese culture. Felix could not bring his entire band, so he pulled together a show using the band Soukous Stars, who now base themselves in New York. Banning Eyre caught up with Felix during a rehearsal at the start of the tour. Afropop Worldwide’s programs “The Congotronics Story” and “Hidden Meanings in Congo Music” were both in production, so in addition to talking about Felix’s career, the two discussed the central ideas in these programs as well. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Hello, Felix. Welcome to Afropop Worldwide. How about telling us a little about yourself?

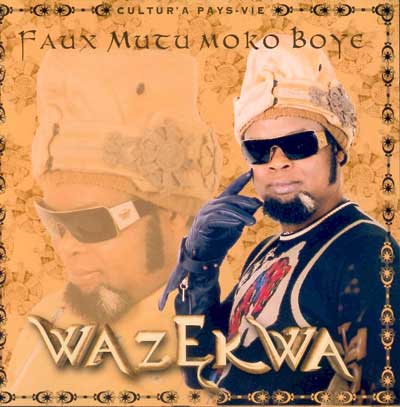

Felix Wazekwa: My name is Felix Wazekwa. I'm an artist - a musician - from Congo, Kinshasa. Before starting to sing, I wrote songs for many Congolese artists and out of that experience as a lyric writer, in 1995, I released my first album, which was called Tetragram. At that time, I was singing in the name of God. On that first album, I was very happy, because I was accompanied by Papa Wemba, and also Madilu System. My second album was also a benediction because I was lucky enough to do a duo with Tabu Ley. Tabu Ley is a monument in Congo, so I had a great experience with Tabu Ley on my second album. Then came my third album, Bonjour Monsieur. This time, I had my own group, which I started in 1998. I've been evolving with this group right up to today. So now, I'm up to my eighth album, which I've just released. It's called Faux Mutu Moko Boye. That is to say, a certain bad character.

B.E: Yes, I wanted to ask you about that title.

F.W: It means a certain bad type of character. A bad man. It's an expression we use among friends. When you have before you certain friends, intimates, you call them Faux Mutus. It's actually the opposite. In reality, this is an insult, but among friends, it's a code word.

B.E: Joking around.

F.W: Yes, joking around.

B.E: I understand that your fifth album, Sponsor, was a breakthrough.

F.W: Exactly, exactly. That was in 2000. That was the first time I brought my own group to Europe to record. That trip really promoted us because the musicians worked under really good conditions, in really good studios. So we were able to make an album that really opened doors for us. With this album, we began our takeoff. I got a sponsor, a very, very big brewery back home, Bralima. Ever since that album, they have opted to sponsor me, and I'm with them up until today. With Bralima, I have been able to do many things, lots of trips, and they put a lot of money into promotion. They promote their beer, but also the group. The group benefits, and especially the fans. So I am very happy with that album because it has become something of a reference for many things, but especially for myself. Since 2000, we've done a lot of touring. We've been out of the country at least 10 times. Just three months ago, I was in Europe with the entire group for a tour of five months. That went very well. At the moment, we are preparing for a tour here in the United States, maybe later this year. So things are going very well.

B.E: That's great. Great group, great sound, and now a sponsor. But you started out as a lyricist. So I'm wondering if part of your success has to do with the words you sing.

F.W: It's true. I got my start as a lyricist, writing lyrics to songs, for operettas, for anyone who needed words. Through this work, I introduced and modified the language of the Congo quite a bit. I introduced lots of phrases and expressions that people still use today. I also had favorite themes. I like to sing about complexes that Africans have. We often have complexes about Europe, about America, about whites, lots of phenomena that create complexes for blacks. So I wrote a song about that called “Complexe,” talking about this phenomenon. For example, you have asked for the hand of young woman in marriage, and she has refused you as long as you are still in Africa. But when the woman discovers that you've gone to the United States, for example, suddenly she says yes. That's going to give you a complex. Does she love a man, or a country? So I talked about that sort of complex in this song.

There are lots of songs like that. Recently I talked about duplicity in a song called “Motema Mabe.” That means a bad heart. Duplicity of the worst sort: bad faith. This too applies to Africans. The enemy of the African is the African himself. The African wants to do harm to someone else, but unfortunately, what he does passes on to his country, his people, as we see in the Congo today. The country is very far behind in many ways. It's not because we lack the means. It's not the poverty of the country. It is the poverty in the heads of people. People have not evolved yet, so I sang a song about that, which people really liked. I have another song that talks about this poverty of spirit on the new album Faux Mutu Mogo Boye.

B.E: This is the album that you've just released?

F.W: Yes, it came out in December, 2005. We recorded it recently in Paris, with the whole group. It's doing well so far. We are trying out a new system. I think this exists in America, but it's the first time we've done it in Africa. When I make a CD, I also put a DVD in it. This way, people have not only the music, but they can see the songs being performed, the dances especially. So I did that this time. I couldn't put all the songs on the DVD, but some of them. This works very well. People come to the shows already knowing the dances, and singing the songs

B.E: Let's talk about some of those songs. Start with the first one.

F.W: “Cas Oyo Benga Nzembo.” That's a song that I sing about myself. It's an introduction. But in the song, I say things using proverbs, the sort of things I like to put in my songs. Today in Africa, we have a habit of starting an album with a very good dance song, a kind of generic song. If we sing in Lingala, not everyone will understand, because a lot of people don't speak Lingala. But if we do a song that is about dancing, everyone finds himself in the dance. When you’re dancing, you don't need words. You only need rhythm. I think this is why we have developed this habit of starting an album with dance song. It makes people move.

B.E: That song uses traditional rhythm, not the rumba or “soukous” rhythms.

F.W: That's right. That's because we want to be eclectic. We want to touch everyone. We don't want fall into monotony. What is good in African music is to put a little jazz into it. We can do that. We can do rumba. We can tango. We can introduce lots of rhythms into the music. If you listen to American music, you won't find all that. We have the opportunity to sing all forms of music in the world. Not only can we use all the dance rhythms from the different regions of the Congo, but we can also put in European or American music. That means there are many colors and our music. It's hard for us to fall into monotony. The main thing is to please everyone. To touch everyone a little bit. That's why there are so many rhythms in our productions. It takes a long time to learn all parts of the song and put them together.

B.E: Yes, I have seen that watching you all rehearse. The arrangements are very rich. You have a lot to drawn on in the Congo. I want to come back to music, but let me ask you another question about the words. On the level of message, what is the most important song on this record?

F.W: I think it might be that one I mentioned, “Motema Mabe.” That song talks about the bad condition of the heart of the African, who is his own enemy. That's the song that has really been pushing us forward recently. You see, now in Africa, people wait for the state to give them everything. They don't try to do anything on their own any more. It's as if the state had a magic wand that they would wave and solve everyone's problems. In this song, I say that people should not depend on the government. We must organize ourselves. The state will do what people cannot do, but we shouldn't count on them for everything. If you want to take care of your home and property, that is not the state's work. If your property is dirty, it's up to you to clean it. It's not up to the state to send someone to clean it for you. I included lines like that to show that we Africans are a little bit reticent. That is to say, we are hesitant to work. In reality, we can work. We have knowledge, ingenuity, many things. But unfortunately, we have today an attitude that says that we should wait for the state to do everything for us, and arrange everything for us. This is why in Kinshasa, we still have mosquitoes. Normally, the mosquitoes would be there as a sign that we are not living our lives properly. But, unfortunately, everyone is waiting for the state to take them away. So we are trying, struggling, to put words in our songs that will encourage people to have hope in life, and in the future. That's it.

B.E: I have been reading about the upcoming elections in Congo. Do you have renewed hope for your country now?

F.W: Yes. About the elections, what I have to say is this is really a new hope for the Congolese. This is really the first time we have voted, and we want the support of Americans. Because the Americans are the most powerful people in the world today. We would like President Bush to help raise the consciousness of our politicians so that we will see a dignified election. We want to believe in the results of the elections. Everyone is happy that we now have a democracy, and we hope that other countries will now invest in the Congo. The Congolese have great means, but they hesitate to invest in their own country because of war, because of the troubles, the security. This is why people who have the means today prefer to invest outside of the Congo. But after we have this election, and if it is a real democratic election, I think that this time things will go well.

B.E: I have the impression that in the Congo, where people have not had a lot of confidence in politicians, musicians have quite a powerful voice. But of course, during the Mobutu time, they did not speak out about politics. What you think the role of musicians is in guiding people now in this new era?

F.W: Today, artists are looked up to, and sought out, because in order to have a political discourse, you have to invite the artists also. It is the artists who reach many people with their discourse. We can play two or three songs, and afterwards the politicians can speak to the public. But we do not want to become too involved in politics, because it's not easy. We basically want to leave politics to politicians. I myself consider that very difficult work. It takes a lot of preparation and education. Me, I consider it a difficult profession. But the role of the artist today is to show that the ability to play concerts is also a fruit of peace. If politicians give us peace, we artists can express ourselves. We can go all over the country. The artist today is someone who reveals whether the country is doing well or badly. If people are suffering from hunger, we sing about hunger. If people are happy, we sing about joy. We reflect the state and the spirit of the country. If things are going badly, we can't stand back and cross our arms. We must speak. We must speak. This is why I think politicians respect us also, because they know that what we sing - our songs - translates the reality of the country.

B.E: So that is more important than singing that this politician is good or bad, right?

F.W: Yes. As you said, in the time of Mobutu, it was true that we could not do that, because during that era, anyone who spoke badly about politics was immediately arrested. But today, we have certain freedom to speak about our choices, and to show if things are good or bad for the country.

B.E: I understand that even during Mobutu's time, although artists could not sing about politics, they had other roundabout ways of commenting on the situation.

F.W: Absolutely.

B.E: You were very young at that time, but what do you think music did for people during that time?

F.W: During that time, we had artists like Luambo Makiadi (Franco), Rochereau, Wendo, many artists of that time who had to express themselves. They were obliged to express themselves, although always in fear of the reaction of politicians. If I said something bad, it was true that they would arrest me. But I do not want to stay quiet. I must speak. I'm still an artist. And artists must reflect the reality of the country, and certain artists, like Franco, did have the courage to speak out, and many times, he was arrested. But because he was in such demand by the public, they always released him. So it is good that we artists today have more freedom of expression, but is not total, this freedom. We are still afraid. We know that there are subjects we cannot broach without fear. For example today, I myself was received last Sunday by the vice president of the Republic, M Z’Ahidi Ngoma—because we have one president and four vice presidents—I was received by this vice president and we spoke for a long time about the politics of the country. This is good, because politicians know that we artists live with the people. People are close to us. We are in a position to explain certain realities to politicians. We can actually explain to them some of the needs of the people, because the politicians cannot live among all the people. But we are among all the people. We do popular concerts. We do VIP concerts. We play for everyone. So I tried to explain to M. Z’Ahidi Ngoma the needs of the people, what the people are waiting for from the Government. And he also explained to me certain realities. In short, it is not easy to address the problems of this country without elections. We must pass these elections.

B.E: Thanks. It is an important moment. Here's a musical question about the state of Congolese music in the world today. In the United States, we recently had a tour by this group Konono No1, under the banner of Congotronics. It was very successful. Young people came out hear this group. I understand that these groups are not especially popular in the Congo, that they are not taken very seriously. So what you think of this phenomenon - these village groups who have come to the city?

F.W: Just goes to show that there are many different colors in Congolese music, even in African music. But lacking publicity and promotion, many groups are not known. The groups that are working out, like me and some other friends, are the ones who have the means. But they're not the means given to us by the state. No. We have done it our own way. This is the problem with making music and our country today. You mentioned this group Konono. There are many groups like that that have a lot of talent, but that never really emerge even in this country, because no one works for them. These days, we have a lot of problems getting visas to leave the country. That is hurting the music. We also suffer from of a lack of good producers. That is why I encourage anyone who is interested in helping make our groups be better-known, to help them to be heard, to get visas, and make an effort. It's true that there are some who have used visas for other purposes, but there are many who won visas simply so they can do their work.

B.E: Right. I think it was a little bit of a surprise for some people here to see Konono. There are some big fans of Congolese music who did not understand why this group was getting a tour, when so many other big stars do not. But people who know very little about Congolese music really responded to their sound. They liked the fact that it was a bit rock-and-roll, not so well produced or arranged, but very authentic. So now there is a bit of debate among Congo music fans here. That's why I'm asking you that you feel about the actual music that group like Konono plays.

F.W: Yes, yes, yes. I think these are the groups that should be promoted. There should be a lot of promotion for these groups who are in difficulty today. They are not known, even in Congo. There are a lot of groups like that who lack a promotion. I don't know exactly how Konono came to the United States, but I congratulate them. We have a lot of groups like that who need to be promoted. It takes a lot of promotion to become known - good recordings, even DVDs. When people can see the image, that's a really good promotion.

B.E: These groups are folkloric, but electrified. I understand that they had some influence on popular groups too, like Zaiko Langa Langa. Konono was a source for the song “Zaiko Wa Wa.” Groups like that took ideas from folklore and put them into modern music. Do you do that in your music?

F.W: Yes, yes. All the groups do. I will take the examples of Franco and Tabu Ley. These are also people who came from villages, and went on to become known in the city. With electric instruments, they modified the music they knew, and mixed it with Western music. They made a mixture of modern and traditional to create the music we have today. Even today, we need that music in order to keep creating. Without it, we don't move forward. This is music that is not very well-known, and that's why I like to make trips to my home region, stay a few days, listen to groups. We must keep alive this music which is very rich, but not very well produced. Today, we hear records only by the musicians who live in Kinshasa. There are far fewer recordings of the groups who live in other regions.

B.E: Congolese music is very rich. It doesn't end. But I think this interview has to. You need to leave, don't you?

F.W: Yes. Thank you.

B.E: Thank you. And I look forward to seeing your group here next time.