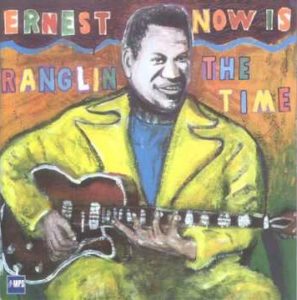

Guitarist Ernest Ranglin is one of Jamaica’s most revered musicians. Ranglin was there at the very beginning as a session player and musical arranger, when Jamaican sound system entrepreneurs began recording local artists on basic equipment. He graced some of the very first albums ever released by Island Records in the late 1950s, worked with the Skatalites at Studio One, was an in-house arranger for Federal Records, in the team behind Prince Buster’s earliest recordings, and was responsible for Millie Small’s breakthrough hit, “My Boy Lollipop,” all the while enjoying a burgeoning solo career, which led to overseas album releases on RCA Victor in the mid-'60s. His contributions to the Jamaican music scene continued into the roots reggae era of the late 1970s, when he cut important sides at Aquarius Records and broadened the sound at Lee Perry’s Black Ark. As he began spending increasing periods abroad, he cut a series of sublime jazz albums, often in conjunction with his longtime friend and collaborator, the pianist Monty Alexander. There were some noteworthy albums in the 1990s too, such as the excellent Below the Bassline for Island, and although the 1997 Baaba Maal collaboration In Search of the Lost Rhythm didn’t work so well artistically, at least the album was out of the ordinary. His live shows have seldom disappointed, and even as he grew older, the man displayed unusual energy, his musical skills seemingly undiminished, and he’d often do wild tricks on stage like playing his guitar upside down behind his back.

Ernest Ranglin’s June 27 gig at the Barbican was part of what is billed as his "Farewell Tour." Since he’s already 84 years old, it's fair enough if Ernie wants to hang up his skates. Yet, since the backing band boasted Afrobeat pioneer Tony Allen on drums, perceptive bassist Ira Coleman, inspiring saxophonist Soweto Kinch (replacing the announced Courtney Pine), and Senegalese singer Cheikh Lô among the lineup, along with Latin jazz pianist Alex Wilson (a longstanding collaborator with Ranglin), expectations were running high--especially since London was still reeling from the disastrous "Brexit" vote that has plunged the nation into utter chaos.

As I reached the warren of brutalist concrete blocks in which the Barbican’s concert hall is situated, I could not help but think of those wretched MPs who have crash pads in the vicinity. The gig fell on a Monday night, and the area felt totally dead, yet the Barbican concert hall was packed, a fitting turnout for this musical legend. Opening act Nerija is a septet of young female jazz musicians that evolved from the Tomorrow’s Warriors Female Collective, one of the many creative initiatives established by Ernest’s nephew, Gary Crosby, to stimulate young British musicianship. Playing an invigorating set of their own compositions, Nerija had the house totally riveted, displaying all manner of talent and with each member evidencing their individual personalities through their chosen instruments. The dual-sax melodies of Nubya Garcia (tenor) and Cassie Kinoshi (alto) fused well with Sheila Maurice-Grey’s trumpet blasts, and trombonist Rosie Turton was a fine soloist. Guitarist Shirley Tetteh had a pleasing understated style, and in a nice reversal of the usual state of affairs, the only white members of the group were the rhythm section, with drummer Lizy Exel keeping complex timing throughout and double-bassist Inga Eichler yielding strong sweeps of melody. Songs like Eichler’s “For You” started with a cacophony of brass noise but soon morphed into a slow crescendo of melody; others went from Euro-jazz to rhythms informed by the jit and jive of southern Africa. They seemed confident and perfectly at ease on stage and had good musical communication among them, despite being in the midst of one of the nation’s premier concert halls, and the excellent acoustics of the Barbican allowed us to savor their obvious talent. The brief set really raised our spirits and it is easy to understand why Nerija has been nominated for Jazz FM’s Breakthrough Act of the Year. I expect great things are in store for Nerija in future, so if they come to your area, don’t miss them.

After a long interval, the main attraction slowly made its way onto the stage, and Cheikh Lô’s momentary stumble when he somehow collided with Soweto Kinch seemed like a metaphor for what was to follow. Once everyone had taken their places, with Ernest Ranglin in a sharp grey suit and Lô in a yellow robe, seated at a pair of timbales, the opening number “Moondance,” from the 2001 Telarc album Gotcha, had Ranglin playing in tandem with Soweto Kinch, but things felt wobbly at first, with the two not totally in time with each other. Once Ernest signaled him to solo, Kinch sounded more in his element, and there was a great flourish of Latin jazz keyboards from Alex Wilson; later, Cheikh Lô had a bit of a flurry on the timbales, as Tony Allen slowed to a stop. “Swaziland,” from Modern Answers to Old Problems, started with sax, bass and guitar playing in unison, with some good soloing from Ernest on his lovely sunburst hollow-body, but Soweto Kinch still seemed a little out of sorts. Then there was a somewhat sentimental-sounding instrumental, with some good soloing by Ernest, and a slow-motion section where Ernest and Ira Coleman locked into a tepid groove, but the ending was another wobble, suggesting a lack a proper rehearsal time.

Once Ernest counted-in the beloved title track from Below the Bassline, there was widespread applause as Ernest and Ira belted out the melodic anchoring in unison. With Kinch momentarily absent, Ernest started doing some rhythmic knocking on the fretboard with both hands, following by scintillating scales. Then Kinch slowly crept back in on saxophone, and the sound felt stronger and more solid. Yet, a stagehand had to sneak across to turn Ernest’s amplifier up a notch, since his guitar was somehow a bit lower than it should have been.

After Ernest saluted a planeload of Canadians that had apparently flown across for the show, there was a change on stage as Cheikh Lô picked up an acoustic guitar to lead “Balbalou,” the title track of his latest album, which had some good call-and-response interplay with Wilson on the piano, yet Lô’s vocals sounded muddy in the mix and Ernest’s attempts to jam in the breaks had the effect of throwing things out of time; Lô tried to speed things up, and after things fell back into place, Soweto Kinch drifted back for a few notes after the second verse.

“Memories of Senegal” was then delivered in jazz tempo, with staccato piano breaks and a nice sax solo from Kinch. Thus far, Tony Allen had been largely subdued in the proceedings (his surprisingly understated beats contrasting with rim-shots and edge-taps from Lô on the timbales), and when he finally launched into a propulsive drum solo, it still felt like he was largely holding back, as Ernest starting a rhythmic rubbing of his guitar neck. Crowd-pleaser “Surfin'” then began with a languorous introduction and soon yielded strong solos from Kinch and Ernest, plus a playful piano part from Wilson. But then, as Ernest drifted into an extended solo with some fancy footwork to accompany it, Soweto Kinch made his exit from the rear of the stage, and that was the last anyone ever saw of him. Was he disappointed with the lack of musical communication on stage? Did he need to leave the premises to go to present his weekly jazz show on Radio 3? Or did he just want to go to watch the football match?

We never got the answer, and even Cheikh Lô was baffled by Kinch’s absence, as he clambered onto the drum kit in place of Allen to start the song “Bamba,” delivered here with funky organ licks and a rhythmic reggae skank. Yet, it was another wobbly number until Ira Coleman was able to anchor things with the bass, and Ranglin’s guitar solo added texture. The next number had a South African feel, with Cheikh Lô dropping in some vocals in French, and Ernest moving things the Congolese way for a time, but we could not hear what he was doing properly; later, Ernest did a fancy solo at the top of the neck, but the drum solo towards the end was pure chaos.

Things had gotten so confused by this point that when Ernest started launching into “Below the Bassline” a second time, the band members were as confused as the audience. Was he unhappy with the earlier rendition of the tune, or had he forgotten that they’d already played it? Or was it just a way of filling time between numbers? In any case, “Ball of Fire” was another crowd-pleaser, marking the end of the set. And the crowd, of course, did not want to let him go yet, even though the set was approaching the 90-minute mark, so the band (still minus Kinch) soon came back for a rendition of “Nana’s Chalk Pipe”—the only number to get a few brave souls dancing in their seats—but Tony Allen was clearly struggling with the time signature, making it feel like an anticlimax.

An Ernest Ranglin concert is always something to savor, and this one certainly had its moments along the way. It can definitely be described as “memorable,” though not necessarily for the right reasons. At the end of the night, I couldn’t help thinking that a “farewell” tour might have been better executed with a band Ernest had chosen himself, rather than one with guest players suggested by outside sources. But in any case, it was good to see that Ernest is still an able player, in good spirits, and with the agility of a far more youthful man.

An Ernest Ranglin concert is always something to savor, and this one certainly had its moments along the way. It can definitely be described as “memorable,” though not necessarily for the right reasons. At the end of the night, I couldn’t help thinking that a “farewell” tour might have been better executed with a band Ernest had chosen himself, rather than one with guest players suggested by outside sources. But in any case, it was good to see that Ernest is still an able player, in good spirits, and with the agility of a far more youthful man.