Read Part One of this report on Festival Taragalte here. It's a unique, dynamic music and culture festival on the edge of the Sahara desert in southeast Morocco.

All photos by Sebastian Bouknight.

Arriving at Festival Taragalte was like a half-waking dream. The long drive to M’hamid El Ghizlane passed through a sprawl of chunky red rock, naked geological uplift and dry riverbeds. Cars of tourists with hiking backpacks pulled up to the center of town as the mosque let out from Friday prayers. Ornate, earthen kasbah hotels peppered the rambling palm groves like a Saharan Beverly Hills. After a 10-minute ride in a flatbed motorbike, swerving around a car stuck in the sand, we reached the grounds.

It was hot and bright, the sun blazing from above and radiating from below. All kinds of sunburned and strangely dressed tourists jostled in line for tickets. Kids from town marched through the gate from the sandy parking expanse.

This place — this festival — has something for everyone.

Encounter

Taragalte has a remarkably broad appeal. Its co-founder, Brahim Sbai, told me that most people come “to leave the quotidian life."

Such was the case for many of the foreigners -- like the Slovakian woman wanting to break the slog of her cement company office job – but also for the Moroccans. I shared a taxi with two guys from M’hamid who live in a nearby city; they traded their jeans and T-shirts for gandoura robes and cheche headwraps when they got to their hometown. One desert tour guide told me he comes to the festival not to look for clients, but to take a break and kick it with friends.

Moroccan city kids set up tent cities under the shade of gnarled tamarisk trees and in every pocket of the dunes. Walking through them at night was like scanning radio channels, with one crew strumming guitar and the next blasting techno and waving laser pointers through the campfire smoke.

A Dutch psychedelic voyager and former techie rolled up with broken glasses and plenty to say about universal divinity and the social media panopticon. Two young Moroccan hippies trailed him, indulging in his camper van and good acid. A Frenchman wearing heart-shaped glasses appeared at every concert, waving a huge heart flag, while, nearby, some local guys waved Polisario flags and lectured fervently about the cause of Sahrawi independence. Young musicians from around Morocco brought their guitars and guembris and jammed under trees.

Though Taragalte was more grounded than I expected, some European (and Moroccan) festival-goers still bathed in fantasy. There was the group of older Germans dressed in bizarre misinterpretations of Amazigh attire, or the couple in white gandouras posing romantically in the dunes. Some young locals made sure to perform the identity expected of them — the mysterious custodian of an exotic way of life — competing for biggest cheche and oversalting conversations with the word "nomad."

The high-priced tourist tents, where the festival generously lodged me, were corralled in a private circle on the outskirts. The aura of the desert might be enchanting, but its mundane reality not as much. “There’s too much sand in my tent,” one Frenchwoman griped.

The tent next door served up a rich buffet of Moroccan dishes -- beef stew, cow foot and chickpeas, lentils, salads, etc. Those on more modest budgets kindled fires and cooked up tagines in the dunes. Nearby, a string of tents run by small-scale local restaurateurs sold tea, cheap, tasty food, and shiny Saharan and Sahelian bric-a-brac.

The daytime activities seemed to be curated for the foreign visitors. Camels raced and people played “nomadic hockey,” neither of which really happens outside of the tourist context. Conferences on nomadism and climate change sleepily took place in the afternoons. An NGO that employs local women to make rugs from old Dutch rags held daily weaving sessions. Sbai led a tour of the nearby oasis, the crumbling ruins of an abandoned kasbah and a town being slowly swallowed by the sands.

Someone had invited a nomadic Sami family from snowy northern Scandinavia, who shared their traditions of clothing, jewelry, reindeer herding and song. While I talked with the father, his boys played on a smartphone, and a Moroccan shepherd from the desert city of Guelmim came up. The two quickly bonded, sharing pictures of their animals and discussing markets, butchering techniques, and recipes (“You wash the stomach, turn it inside out, fill with with other organs and hang it in the sun to dry? We do that too!”)

More than just putting on some annual fun, Taragalte actually seems to build community. I met many artists and festival-goers who come back every year, building friendships, starting bands, maybe even finding love.

Music

As the sun started to sink from its searing heights, the local families and folkloric music groups came out. Musicians from the Arab Sahrawi ‘Arib tribe played chamra, a dance of handclaps, voice and bowl drum.

An Amazigh (Berber) group performed ahwach, a mighty, top-of-the-lungs style of call-and-response song, exchanged between a line of men with frame drums and women dancing in black shawls.

Men dressed in all white performed ganga, a branch of Gnawa music, except without the guembri lute. All of these communities make M’hamid, a long-time meeting place for Saharan caravans and cultures, what it is today.

The setting sun drew a pilgrimage to the crests of the biggest dunes to soak up its luscious orange and red. Once its fire cooled to deep blue, the main stage came to life.

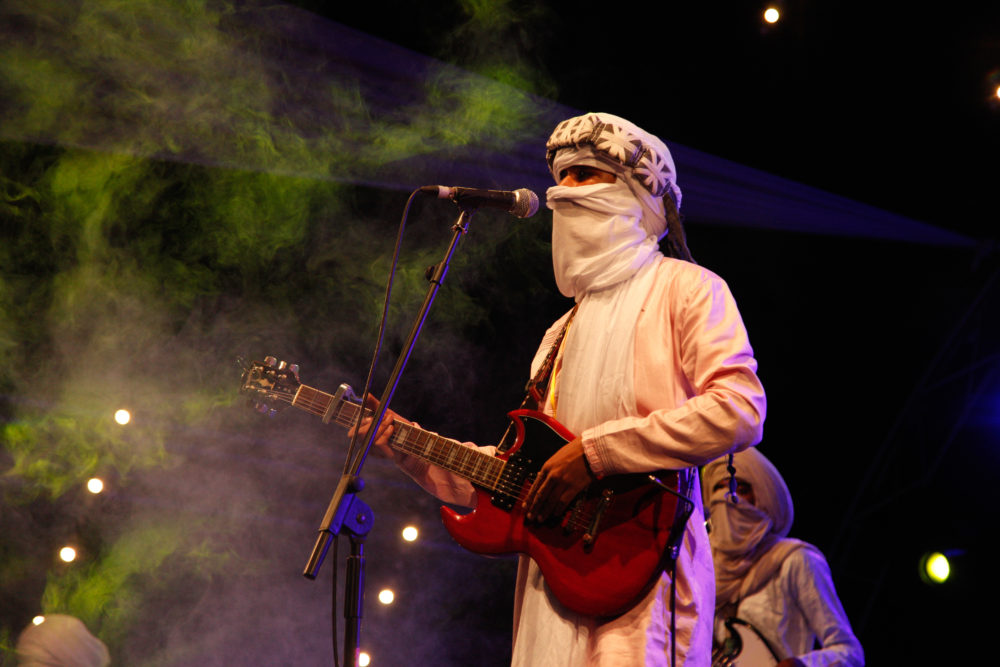

The lineup was heavy on desert blues, and much of it local. The M’hamid area is home to a thriving crop of young musicians who draw from the generous well of local traditions as much as from rock bands across the Sahara.

Les Jeunes Nomades de M’hamid, Joudour Sahara, Generation Taragalte, and Tarwa n-Tiniri are all bands hailing from Morocco’s southeast. To varying degrees of success, they make the loping, expansive Saharan blues sound their own. “Taragalte is a platform for all the young talents who want to play on stage,” Sbai told me. “We have a real impact on the youth of M’hamid.”

Generation Taragalte, founded after its members saw Tinariwen perform at this very festival seven years ago, is probably the most veteran of the bunch. Saïd, one of the lead guitarists, is an adept player. Their music has taken them on tours in Europe and around Morocco, but they told me that no matter what heights they reach, M’hamid is home.

These bands write originals, but covers of Tinariwen and Tamikrest are a must, even though they can’t always understand the lyrics. Their idols are Tuareg, or Tamashek, an indigenous ethnic group related to yet distant from the Amazigh of M’hamid. The Amazigh members of Generation Taragalte can parse out the songs’ meanings for those who only speak Arabic.

Joudour Sahara, a music school recently founded in M’hamid, has propagated Saharan blues and local folklore in the oasis. Youth from the town came in droves to listen to their rockstar neighbors (like I did with the local punk bands in my suburban hometown).

They enjoyed themselves ferociously. The young crowd — mostly teenage boys — seemed in constant flux between dancing ecstatically and throwing punches. “When they hear electric guitar, they go crazy,” Khalifa, of Generation Taragalte, told me. Some flavor of chemical intoxication turned the heat up, and the rebellious lyrics pushed it a notch further. But for every fight that broke out, the dust would settle and everyone would start dancing again.

Meanwhile, one European, swaying to his own beat on the other side of the crowd, exclaimed dreamily, “Can you feel Africa?!”

Kader Tarhanine put on a great concert. The young guitarist, born in Niger to Malian parents and now living in Algeria, lays bare the absurdity of the national borders imposed on his community. He’s one of the most popular Tamashek musicians across the Sahara today, coming into a solo career after fronting the band Afous d’Afous. Tarhanine (a pseudonym meaning "my love") is a romantic, but also sings about the struggles of the Sahara and the need for solidarity. The Taragalte crowd adored him.

And he brought a very special guest: Lalla Badi, the 85-year-old matron of modern Tamashek music and a fellow resident of Tamanrasset, Algeria. Grand in repose and commanding on stage, she’s toured North and West Africa, Europe and even Japan after the recent release of her first album. Tinariwen’s frontman Ibrahim Ag Alhabib spent his formative years at her house, learning her songs and the rhythm of tende music. In some ways, Taragalte is thanks to her.

The culture they share with M’hamid is not so much based on ethnicity, but on land. The desert, and the nomadism it once demanded, is a bridge stretching from Morocco to Niger. But with borders now blocking movement, music is the connector.

There was music from beyond the Sahara too: From Mali, the singer Salomé Dembele played a bubbly music rooted in the sounds of the Bobo ethnic group. Her balafon player, Kasim, was a total face-melter, playing that marimba-like instrument faster and more creatively than I’d ever seen.

Samira’s Blues, led by the Dutch-Moroccan singer Samira Dainan, cooked up a sweet, spare take on desert blues, while Aziz Sahmaoui, a veteran of the Moroccan music scene, rocked out a thick blend of Gnawa, Malian kora music, phased-out Saharawi guitar and reggae.

The concerts were raucous fun, but things truly clicked during the unpolished late-night jams, with a crackling fire nearby. Every night, after a laser pointer-wielding astronomer turned the sparkling sky into a planetarium, musicians gathered in the back of a big camel-hair tent. Lit by candles, they jammed on Saharan blues till Orion reached overhead around 3 a.m.

It may sound cliché, but the desert really is the perfect habitat for such sounds. It just makes sense there. The reverberating, layered guitars and loping, lolling djembe nestle perfectly into the dark landscape of rolling dunes and rocky sprawl.

The bustle of the festival electrified a place that normally is deliciously mellow. I stuck around for several days afterward, sucked into a rhythm that was infectiously slow. There was always someone napping on the thick carpets in the corner of a tent, smartly saving energy under the midday sun. When things happened, they did so spontaneously. In between naps and spurts of work, everyone ate together from a huge dish. Private property was an afterthought — jugs of water, glasses of tea, sleeping space were shared without a word. The tent was a place that could become anything it was needed for — work, eating, praying, performing.

And sand got in everywhere, eventually. The desert wants to make you it. Taragalte sure helps.

Related Articles