We met the legendary FOKN Bois—Mensa and Wanlov the Kubolor—at Wanlov’s place in Djorulu. A Kubolor is a kind of street person, but Wanlov’s pad looked pretty nice, with a friendly monkey out in the yard—the same monkey used in Sister Deborah’s sexy, absurdist video “Uncle Obama.” We sat down for a chat without much idea what we were in for. Suffice it to say, there is nothing in African hip hop—or African music of any sort—that quite compares with this daring duo. I have described them as “the South Park of Ghanaian music.” The idea is that there are no sacred cows in their world, but they dole out satire with such lovable wit, that it’s difficult to be truly offended. Here’s how the conversation went down on our first full day in Accra.

Banning Eyre: To start, why don't you guys just introduce yourselves?

Mensa: My name is Wanlov the Kubolor. Also known as the African Gypsy, the Pastor Wives' Sexer...

Wanlov: That is, if you were me. And if I were you, I would be Mensa the Magnificent Menstruater.

M.: That is if you were me. No, seriously, my name is Mensa Ansah, one half of the FOKN Bois. A Ghana boy. Not buoy.

W.: Yes, not buoyant. And I am Wanlov the Kubolor, African Gypsy. Other half of the FOKN Bois.

B.E.: Tell us your stories a little bit. How did you guys become musicians?

Mensa (Eyre 2013)

M.: I would say it's almost accidental. But also, I didn't really have a choice. I just started by playing the piano, listening, and just being really interested in writing a couple of things here and there. And then, as I grew up, I was doing it more and more. And in that process, I met up with Wanlov here in high school, and we started writing music together. Just really as a fun thing.

W.: But, how come there was a piano at your disposal?

M.: Okay. It's crazy. It was not because my father was a musician or anything of that sort. Which he was. But it was because my best friend had a piano at home. And I used to go and spend a lot of time messing around. And I started bugging my mom for a piano. So she said, "Okay. If you're going to do this, you're going to do this properly. You're going to have two hours of lessons five days a week." And then, of course I started hating piano. I mean, if I missed my lessons, my mother would beat me. You know? Yes. In Ghana, it's okay to beat your children. Really, it is. With anything in sight.

W.: Yes.

M.: Yes. You know? Pan and cable. All those things. And then, as I grew up, I realized it was the only thing I was really passionate about and I could do "properly." So I said why don't I just do this is a full-time career?

B.E.: So, even though you hated the piano, you did learn from those lessons.

M.: Oh yes. And once I discovered rap music, it was over.

B.E.: How did that happen?

M.: Through my brothers, and MTV. This was the early to mid-90s. But I was lucky, because my eldest brother had been listening to hip-hop since its inception. So I got a chance to listen to all the early stuff. Then after a while, I started discovering my own music as well, and then introducing my brothers to stuff.

And then because I could play a little bit of piano, I started messing around with my own beats and stuff like that, and creating ideas and things. And then, anytime I was in the studio, I seemed to be more interested in what the engineer was doing. I had a friend, David Bolton, who said, "Okay, if that's the case, come and clean my studio every morning, and once it's ready, I'll show you how to use the Korg Trinity," which was a keyboard that allowed you to create everything on different tracks. So I really got into it then. And this is me now.

B.E.: You said your father was a musician. Any relation to ET?

M.: No, no. Mensa is my first name. Ansah is my last name. So no relation to E.T. Mensa.

B.E.: No, I meant the Extraterrestrial.

M.: [LAUGHS] Oh! See where I take it. Man, I'm just going down my straight lane.

W.: But your father.

M.: Yes, my father was a guitarist for Osibisa in the early days. He wrote a few songs. I recently had a conversation with my dad, and he really went into how he felt really jilted by the band, a lot of politics. Because he was supposed to be touring with the band. My older brother was conceived. In my mother's stomach, so he didn't go on tour. So he was replaced. And then his songs got published and he didn't get any kind of... yeah so it's really not a nice story.

B.E.: He was bitter over that.

Tumi Ebow Ansah

M.: Yeah, yeah. But he got over it. Because my dad was an actor, a trained actor in Britain, Tumi Ebow Ansah. He was in Heritage Africa, from the '80s. I don't know if you know that. He did a lot of roots and African pop. And "His Majesties Sergeant," which was recently re-released as well. Actually it was the first film that shot in Panavision in Africa, and it starred my dad. So he's a proper, seasoned actor, and now he lives in California. He's been living there for the past 15 years as a freelance actor, and traditional person to go to. And he does some kind of freelance...

W.: …rituals...

M.: Yes, rituals. Though he's a Hindu as well. Yes. My dad has been a Hindu for 35 years now.

B.E.: How did that happen?

M.: I don't know. You know, my dad grew up in Britain. And in the years of the hippies and hugging a lot of trees. And he's been that way since. So when I was a kid, actually, I used to go to monasteries and I knew some of the prayers.

B.E.: Okay, Wanlov, a little biography from you.

Wanlov the Kubolor (Eyre 2013)

W.: Now, you're going to see the difference. My father, I heard he picked up guitar from time to time, like I do now. Just to entertain his friends. But he was a collector of music. Blues. Traditional. West African music. And my mother, a Gypsy, classical Romanian music. And I just listened to it in the house and danced. And we had a piano, but I think it was by accident, because when I started playing the piano, my father gave it away. Years later, I go to visit my aunt, and the piano is there.

M.: That's mine!

W.: Just collecting dust. And I was like...

M.: You messed up my future!

W.: Yeah, that's it.

B.E.: So, how is it you have a Romanian mother and a Ghanaian father?

W.: In Nkrumah's time, there were a lot of relations with the Eastern Bloc. And so a lot of students after high school got scholarships and went to study in Germany, Romania, Bulgaria and so on. That’s how my father met my mother. He was going into petrochemical engineering. And that was where him and my mom did a sin.

M.: Did they do it before they were married?

W.: Yes, before they were married.

M.: No! Nkrumah wouldn't be happy.

W.: No, he wouldn't.

[WE HEAR SIRENS]

Accra street (Eyre 2013)

B.E.: Wow, it sounds like Brooklyn here.

M.: Yes. Maybe it's a motorcade passing. Maybe it's the president.

W.: Yesterday, we had just driven up here after doing some filming. There's a team from Switzerland in town, and they're doing a film documentary with us. And just as were pulling back to the gate, I was on a bicycle, a police car pulled up behind their taxi. Four or five police surrounded us. And they came up to me first, and they were like, "Why have you ejaculated?"

M.: What?

W.: "Why have you ejaculated?" Basically, my cloth was a bit thin. Maybe there was an outline showing. But I was not even erect. Now the police are, "Why have you ejaculated? Who are these people? No. Park the bike. Why have you ejaculated?"

"What? I can show you that I have not ejaculated." Anyway...

B.E.: It sounds like they knew you. Maybe they had watched your videos...

W.: Yeah, yeah, exactly. He knows me as the guy who showed his penis to the TV hostess. "Oh, you're that guy. I have your picture on my phone." One time, the police stopped us at a barrier; they were trying to get money out of our taxi driver. And then they recognized me. They were like, "Come, come, come." And then they show me a picture of myself, exposed. I said, "Thank you."

B.E.: The joys of celebrity, right? So, you say you started at doing this for fun. When did it become serious?

W.: You think this is serious?

Mensa and Wanlov (Eyre 2013)

M.: Actually, it was not serious then. Because we would skip class, while our parents were paying for our premium education [at Adisadel College, Cape Coast, Ghana]. Wanlov would just walk into the class and tell the teacher that another master was looking for me, and I had to be excused from my literature class. And we would go sit in an empty classroom or the dining hall, and the drum on the tables and write rap music.

W.: That's what made us good rappers.

M.: Yes, very good rappers.

B.E.: Now, Jesse Shipley says in his book that you guys represent a kind of evolution of hiplife, or Ghanaian hip-hop, coming out in the original stuff that Reggie Rockstone was doing. That was very focused on America. And you guys are part of a movement to kind of bring it back home in certain ways. What do you make of that? What were you trying to do when you started making recordings and videos?

W.: To be better than Reggie.

Reggie Rockstone (Eyre 2013)

M.: Yes. But to come back to what you are saying about Reggie, I think what Reggie did was very necessary. Because in Ghana, all the music that the young people were listening to was from America, and he had come as somebody from that part of town, bringing something that we could make ours. But it's a process. So maybe he had those kind of Americanisms or whatever, but it was very necessary. Because he was the only person who came and really represented the language. And he was very good at the language, and making it really cool. Because back then, nobody wanted to hear anybody rap in Twi, or make any kind of Ghanaian references. The more Yankee references you made, the cooler you were. But Reggie kind of made it...

W.: ...cool to be Ghanaian.

M.: Yes. So I suppose it was just the beginning of things. And through the years, it's come to this. But it's really just a continuation of what Reggie started.

W.: Now, it's gone a step further, to say, "We are now making it cool to be a free-thinking Ghanaian." I think that's the next step that we have taken.

Wanlov and Banning (Barlow 2013)

B.E.: You guys take on a lot of touchy issues. Nothing is off-limits it seems. So maybe for listeners who are not familiar with your work, you could introduce a few of your songs, and talk about what's behind them.

M.: Okay. I will mention the song, and then you tell them what we were thinking.

W.: Okay.

M.: "Thank God We are Not a Nigerians."

W.: It's just an honest telling people where to go. [LAUGHTER] No, if you go back to the early beginnings of hiplife, this jama style of hiplife, where hiplife was very identifiable as a unique sound, Nigeria was still doing a very rap, hip-hop sound—very traditional. They hadn't yet found that balance that hiplife had. So hiplife actually inspired the likes of P-Square, you know, to create a sound that came out later from them. And then, if you go further back, there were certain elements of highlife that inspired Fela. So, in a way, Ghana has always, even though we were economically the little brother of Nigeria, musically, I feel we were more mature.

And we came out with that song at a time where we were very tired of our fellow Ghanaian who speak to us in an American accent, a forged one, very well forged. And there was now a new phenomenon, because these new Naijapop acts were growing up, and they had the clout to make

it on MTV Base, and they were on our radio stations, because they had the money to pay our DJs and so on. So the youth in Ghana started picking up a Nigerian way of speaking. And it really irked us. And so, "Thank God, we are, not a Nigerians" was a kind of tongue-in-cheek response to that.

But at the same time, the main joke in there was that Nigerians are very proud of their traditional way of living. The way they have fused it with so-called modern life. So you won't find a Nigerian wearing an Armani suit, because they like their traditional agbada. You won’t see them eating pizza and hamburgers and stuff, because they like their local food. And the Ghanaians are not as proud as that. We will do that in secret. But in public, we dress Western. Like anytime you see a Nigerian president overseas, he will be wearing a traditional Nigerian outfit. But our president from Ghana will be wearing a suit. And so we were actually speaking about ourselves. It was one stone and many birds at the same time, with Ghanaians and Nigerians both saying that they are better.

B.E.: A number of people have talked to us about this phenomenon where musical ideas start in Ghana and then get popularized in Nigeria. It goes back to the Afro funk story, and as you say, Fela figures into that..

M.: Right. Fela's first recordings were actually made here in Ghana.

W.: Okay, I'm going to do this one. "Strong Homosexual Guys."

M.: I don't like that song. No. "Strong Homosexual Guys"-- I think, really, the song was about how homophobic we are here in Ghana. I suppose most men are. The chorus goes, "We know they fear guns. We know they fear knives. We only fear strong homosexual guys." And the political take on that is how we've kind of allowed foreign army bases to set up here in Ghana. They've taken people who have lived there for hundreds of years, removed them from there, and set up foreign army bases, and that's okay. But if a gay person was standing outside right now, there's going to be some kind of tension. Our attitude towards homosexuality is like that. But when did a gay person pick up a gun to shoot somebody? When has a gay person hurt somebody because of their homosexuality? When have they been a threat? So it's really just talking about our kind of homophobic nature. And it's not specific to Ghana but, I suppose, most parts of the world.

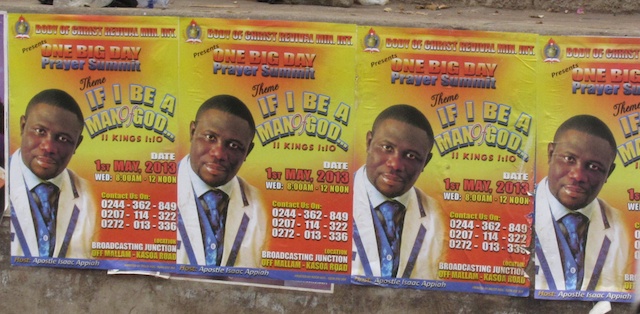

Accra posters (Eyre 2013)

B.E.: But it is strong in Ghana because of the church.

M.: Yes. Yes. The religious influence is major. This actually is a good point because some of the pastors, preachers and whatnot are committing hideous crimes. Child abuse. Sleeping with other people's spouses. All kinds of fraudulent activity. But nobody talks about that. It's just you're gonna get judged by your sexuality, your own private, personal choice. And so the song, really, was about us, Wanlov and myself, after finishing a show, getting invited to this after party. They told us they were going to be loads of girls. We get there, and it's only men, and the bouncer is holding hands with the promoter. And they seem to be coming at us. And then they start chasing us, running after us. I escape. He doesn't escape. He gets... sorry for this. He gets raped, by a strong homosexual guy. Because that's what homosexual guys do. They rape other men. So it was just a play on that. But at the end, we find out that it was just a dream.

W.: A homophobic dream.

M.: And even after the dream, I invite him to a party where there's actually going to be girls, and he says he won't come, because he just had a homophobic dream. So in the last few months, there's been a bit of trouble with one of our ministers protecting the human rights of homosexuals here in Ghana.

W.: Yeah, she got hell from the churches, the media. They really got nasty on her. And we said a few words in support of her as being someone we've known for a long time who's been a very strong advocate for human rights. And so we asked people to respect her. And then it just started...

M.: We got a lot of threats.

W.: Yeah, they were very non-gay people saying that they wanted to probe our anuses with hot metal...

M.: ... and show us how it's really done.

W.: How it's done, yes. There were a lot of threats. They said our parents were gays.

M.: How is that possible?

W.: I mean, we have children. So they could at least call is bisexual.

M.: And again, they just called us gay because we were supporting and protecting human rights.

B.E.: When did that song come out?

W.: Valentine's Day, last year.

M.: But when this issue came up recently, people thought that we had just released the song.

B.E.: I don't imagine that the song received a lot of radio play.

W.: No, no, no.

B.E.: In fact, I imagine that most people hear your music on the Internet, right?

M.: Yes, and when something pops off, then they find a song that connects and say, "Oh they just recorded a song about this." But it's been sitting there for a whole year.

Wanlov and Obama monkey (Eyre 2013)

B.E.: I am impressed that you're so out there with these sensitive topics. Nobody else is doing that, for one thing. But also, this is how change happens. I mean we've seen an amazing evolution on the gay issue in our lives, in our country. The president backing gay marriage is something that would've been unimaginable just a few years ago. It's going to be a slower process here. I've done a lot of work in Zimbabwe, and I know how strong these attitudes are.

Sean Barlow: The main way that attitudes have changed in America and Europe, I think, is the fact that all it takes is knowing someone. Once it's someone close to you, all of a sudden, "How can I be against this?"

W.: So that's why it's slow here, because we are still forced to hide it.

B.E.: Let's talk about religion. We just watched the video of "Sexin' Islamic Girls." Was there any blowback on that one?

M.: That was just really being naughty. I mean, we just kind of thought, "Well, Christians talk about sex and have a very liberal sexual expressiveness. How come Muslims don't?"

W.: And I would put it like, Muslims try to flex like they’re more holy than the other religions. But we know some Islamic girls who have very colorful sexual lives. And so this song...

M.: ... was a tribute.

W.: A tribute to them. And later, a lot of Muslim girls came up to us, and they love the song. The feminists hate the song, and I can see why. But at the end of the day, it's like, if you are a feminist and this song is empowering other females to feel free about their sexuality, who is more feminist then? It is a form of objectification, but maybe it serves a different purpose. But we got through it. Some of our friends in London told us we shouldn't go back to Ghana.

M.: “Don't go back to Ghana.”

W.: “You guys should not come back. The guys are looking for you. From the Muslim population areas.” I was just playing basketball, and these guys were asking me, "Why did you guys go and do that? Why did you say that?" So we were worried. But then we go in the neighborhood, and people are taking pictures with us.

M.: It's never come up. It's never been an issue.

W.: Never. The Nigerian issue has come up more than the Islamic girls. And then there's Old Faithful, Yesus Christus.

M.: Yes. "Jesus is Coming."

W.: Now, Mensa and I have this theory that if Jesus showed up right now in Ghana, and everybody knew it – “That's Jesus right there!” -- and he was walking down the street of churches, and all the members came out and started filming him -- "That's Jesus!" --the pastors would be upset.

M.: So upset.

W.: And then they would all come together and have a meeting. "Look, I was just about to buy a yacht. And you were just about to get a new church. And this Jesus guy came. The timing is not good." You know what? Let's come together. Let's kill him, poison him or something. Then he can come back later. I think this is a very probable scenario.

M.: Ditto. I think if Jesus were to come now, the pastors... Forgive me. I think the idea or the concept of Christianity is sold on the idea that Jesus is coming one day, and not knowing exactly when he's coming. So just stay believing and keep the faith. He is coming one day, but we don't know when. It's almost like going to a bank and saying one day the profits are going to be returned, but we can't tell you when. If you don't get it in this lifetime, then in the afterlife. You know? So, if everybody asks for their money, what are the banks gonna do? They're gonna shut down. I think that's how it would be if Jesus were to just land, say, here in Accra.

B.E.: I remember when I was here 20 years ago, I took a bus up north, and it was one of those buses where seats fold in to fill the aisle so you're really locked in to a grid—no way out. And as the the bus left, this guy got up and started preaching, into a megaphone. It was loud, and quite excruciating, for hours and hours. I've been exposed to a lot of evangelism in America, but this was really aggressive, in public transportation. But these days, looking around at all the billboards around Accra, it seems like churches are stronger than ever. So, again, I think it's brave of you to take this on. Are there other artists who are willing to do this kind of stuff, point out these ironies?

W.: Not among the musicians we know. But we have Mutombo the poet, a good friend of ours. He addresses these issues in his poetry. We have a few friends who are into this, maybe DJs and so on. But it's very hard to survive from the music, and then usually you have to line up with some corporation, like a telecom, or some kind of electronics company. Samsung. And then you find out the boss is Christian. And the staff is Christian. And they can't have that. So for us, we take it as a therapy. Because we see it growing around us. We feel so helpless. We just talk about it so we won’t explode.

B.E.: And you talk about it in a very humorous, friendly, musical kind of way. Makes it all go down easy. But I'm sure it's provocative in certain circles.

W.: This song, "Jesus is Coming," is actually played on gospel shows, because they don't know that the whole song is sexual innuendo.

M.: Yes. The whole song is about sex. The thing is we just kind of thought, why don't we write verses where depending on where you're standing, which angle you're listing from, it could be about a sexual experience...

W.: ... or a holy experience.

M.: So, I think I'm going to let you do this one.

W.: No, no, no. It's yours. Because your verse reveals more than mine does. Mine is more inside jokes.

M.: Well, I say, "Place the Rod," which is trying to say, "Praise the Lord," but most of our Ashanti brothers and sisters have problems with...

W.: ... L and R.

M.: Yeah. So when they want to say "Praise the Lord," they would say "Place the Rod." "This verse is taken from the Book of Romance, the part about the enjoyment of flesh between mans and womans. The book is so elaborate. It goes further to explain that for the coming to be breathtaking, use your brain. Kneel on your knees, beseeching the holy power. Open wide and receive. Believe, and don't cower. For the Rod of the Lord gives in abundance. Those who run from the coming will live in wondrance, never knowing what sweet manna tastes like. Do you fear to swallow the truth and taste life? For sin is an acquired taste. Man is full of goodness. Don't let it go to waste. Be full of grace and face the snake's temptation. Heavenly gates await the Lord's penetration. Evil period, Moses; the sea of blood, Get serious Noah, prepare for the great flood. Get serious. Prepare for the great flood. Jesus is coming, Jesus is coming, Jesus is coming, one day, one day."

W.: And of the average Christian pastor will listen to it, and they just hear holy things.

B.E.: Even now? Surely by this time, people have figured it out.

W.: No, now, they just know there's something up.

M.: Yeah, they just know that these guys must be up to something, because they're just mischievous.

W.: Even if we do a clean thing, they'll think, "No, no, no, there's something bad about it."

Continue to Part 2 of FOKN Bois: The Cutting Edge of Satire in African Hip Hop.