It is fair to say that the original inspiration for Afropop Worldwidecame from Nigerian juju music, specifically when King Sunny Ade and his African Beats toured the United States in the early 1980s. KSA’s lengthy, unraveling shows featured some 18 musicians on stage, a crush of drums, shakers, electric guitars, voices and dancers that knocked first-time listeners, including Afropop’s creator Sean Barlow, clean off their feet. Nigeria has emanated successive waves of music since, most notably Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat, a sound carried forth by boisterous, brassy ensembles all over the world these days, and more recently, Naija pop (Afrobeats), polished party dance music that is to our era what Congolese soukous was to the 1980s.

But none of these sounds delivered quite the roots-pop punch of juju, with its battery of percussion: gangan (talking drum), sakara, omele, iya ilu, gudu gudu, dundun, shekere, all mixed up with interlocking guitar and vocal lines. As it turns out, the ‘80s, the very years when King Sunny Ade took the world by storm with his juju juggernaut, also saw the decline of juju as the dominant pop music style in Nigeria. It was not overtaken by Fela’s Afrobeat, but rather, by an even more rootsy pop style, fuji. Fuji bands in those days rarely if ever used guitars, keyboards or horns. Concerts and recordings offered a barrage of percussion and voices, with few tracks running less than 15 minutes. Americans got a brief shot of fuji in the ‘90s when Adewale Ayuba and his fuji band spent some time in New York City recording and performing. But lacking an ambassador with KSA’s means and star power, the genre never really broke through abroad the way it did in Lagos.

As Sean and I planned our Hip Deep field trip to Nigeria in early 2017, we were determined to take the pulse of juju today, and to delve into the fuji story as one can do only in Lagos. There is a fine scholarly book on Juju, Chris Waterman’s Juju: A Social History and Ethnography of an African Popular Music (Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology). But no comparable volume seems to be available on fuji music. University of Ibadan professor Paul ‘Wale Ademowo published two books on fuji in the ‘90s. The history of fuji music in Nigeria (Ibadan, 1993) and The king of fuji music: Dr. Wasiu Ayinde Anifowoshe Marshal (Ibadan, 1996). These are now out of print, and we learned of Professor Ademowo’s work only recently, after our return from Nigeria. We’ve also since learned of Dayo Odeyemi’s Sikiru Ayinde Barrister (Ibadan, 2001). As we note in the program, there’s a big opening for a comprehensive and up to date volume on fuji.

In any case, unlike most of our Hip Deep endeavors, we ventured forth without the benefit of a great deal of scholarly guidance. That said, we gained tremendous insight into the history and enduring importance of fuji in particular. We were told that fuji artists don’t generally like to give interviews. Some say this is because they prefer to speak only through their lyric-heavy songs. Others say they don’t tend to speak the Queen’s English and are often self-conscious about that.

But working through channels, we were invited into the homes of four of fuji’s biggest contemporary stars. The interviews they gave us were both generous and deeply informative, and occasionally contradictory, even if not delivered in the Queen’s English. What follows is a set of excerpts from those interviews, also interviews with juju artists not well known to American audiences, and comments of a few industry professionals on the subjects of juju and fuji. You can hear all these artists and their music on our Hip Deep in Nigeria program “Lagos Roots: Juju, Fuji and Apala.” We sincerely hope that this work will inspire further scholarship, particularly on fuji, a rich, fascinating and deeply revealing world just awaiting sustained and serious study.

K1 de Ultimate, formerly KWAM 1, formerly King Wasiu Ayinde Marshal, and born Wasiu Ayinde Marshal, is officially the king of fuji music. The naming and titling of fuji artists is a complex and at times controversial affair—a subject for another time—but most fuji fans do recognize K1 as the top man. He received us in the town of Ijebu Ode at a mansion fit for a king, with gardened grounds, a palatial home, and a veritable zoo of exotic birds, gazelles, tortoises, a water python and a pair of ostriches he occasionally releases to romp about the grounds with him, even though it can take three days to coax them back into their enclosure. We begin with him.

Fuji music started from here: Yoruba land. It’s mainly something played by the Yoruba. It is the music of our forefathers. The word “fuji” means fun, but with a question mark. What is your fun like? What is your fuji like. Fuji means fun. At first it had an Islamic undertone, because they used the fuji of then to celebrate people during the Muslim fasting period: the call to prayer, the call to fast, during Ramadan. What is later known as fuji used to be called ajisaari or ajiweere. Ajisaari is a participant in the Islamic fasting period. That is the person who calls people to gather to fast. Sari is when they wake people up to observe the fasting preparations, in the early morning. Ajiweere means the group of musicians doing that.

They sing about happenings in the society. They use it to educate people to advance the life of the common man, and not just entertainment alone. They take you down memory lane, the memory lane of your forefathers. They tell you stories of your area. They go into history. They go to the archive. They praise you. They call your lineage. They do all sorts of things.

When I was young, my father died. My first year in secondary school. And he was married to a woman who is not educated. My mother at that time did not know seriously the value of education. My father was an educated person. He knew the value of education, and I lost him. You can imagine that is a problem for me, that I dropped out of school. My mother wanted me to come and join her in her business. If my father had not died, I would still play music. I would still be great. But I would have a university degree. I know that for sure.

But his mother did teach him about music. She sang a style of women’s music called waka.

Waka mainly was for women. You hardly see a man that does waka. They will do sakara or apala (other forms of Yoruba praise music), or fuji. My mother is one of my backbones. She taught me and prepared me when I wanted to go for competition, or what we call discoveries. She would be the one that sits me down together with other males and to teach me things and give me narrations and stuff. She taught me a lot. She’s still around. She’s 99. These competitions are where they discovered people like us. Competitions were being organized by Ramblers Association. Many associations like that had come to develop ajisaari and make it what is later known as fuji. The competition becomes a very serious thing. They test your IQ. You must be very familiar with things around you, conversant with the history of our culture, our people. They want to showcase all that culture.

I started performing when I was 7 years old. And I was nurtured from the junior category. By the time I was 15 years old, I had clinched all the trophies, from the junior category to the intermediate category and the senior. And when you get to the senior category, if you like, you can remain there, or if you like, you can take up music as a profession. So I went pro. I turned pro when I was 15. I had my direct boss, the late Sikiru Ayinde Barrister [Along with Ayinla Kollington, Barrister is considered a father of fuji music.] I had my tutelage under him. I lived with him until I turned pro. If you look at his production of “Fuji Garbage,” that’s a street con word. He was trying to make a statement, an expression, like when they say “bad,” when they mean “good.”

Lagos musician Beautiful Nubia put the “Fuji Garbage” phenomenon in context, explaining that the music was had a low status in the beginning. Nubia said, “At the beginning it was the music of the Muslims. And then when the younger guys came in and started adding innovations, they were not singing about Islam anymore. And then it changed and became a bit faster, at some point, it earned fans from across the country. But it also used also be the music of the poor. The more elitist Yorubas would listen to foreign music or juju music or highlife. And the poor people listened to fuji. But now I think it’s gone beyond that. It cuts across all classes. It’s still not the music of the elites. They might say, ‘Sometimes I listen to that stuff, yeah.’ But it is still more the music of the ghetto.

K1 de Ultimate: Olubadan of Ibadan, the king of Ibadan now, is the one who discovered me, and took me into the studio, and I started to release albums. My boss then was Chief Adetunji. But now he is the King of Ibadan. I worked with them until about five or six years ago, before I established my own label and recording company.

King Sunny Ade was crowned king of juju music. And he has his position as KSA, King Sunny Ade. He is a prince too. He was born into a royal family. But he was crowned the King of juju music. When you do it right and do it well, our people, they know who is the best among the rest. I would also say, it’s another way of giving you a task and a responsibility to say you are the chief now. Don’t rest on your laurels. Keep doing what you’re doing. Because you have people behind you.

Why all the different names?

It’s done by musicians everywhere, all over the world. Music is attached to names. It’s like you are rebranding and rebranding and rebranding by name changing. It’s good for business. It’s good for showbiz. I’m sure you’re very much aware of even in the West, when an artist changes his name. P Diddy changed his name. And look at this artist Prince. He was used to being known by one name, before he woke up one day and says, “Artist formerly known as Prince.”

Anyway, as time goes on, modernization comes. We take fuji music out of its Islamic undertone and bring it to the limelight. And we have the present-day fuji music that is full of all instrumentation, percussion. It becomes world music. Fuji has been showcased at the WOMAD Festival, at WOMEX. We have to taken fuji around the globe. The era of good music today is country music. Look at all awards. In the last five years, which group clinches the best awards? They are the country music. So fuji is country music of here, because it has meaning. Their lyrics have meaning. They lace it with serious words. And people know the value for the money they invest in it.

Glory to God Almighty, I would see myself as the reason for many young folks taking up music. If he can do it, then we too can give it a shot. I named my band then Fuji Revolution. Why do I call it Fuji Revolution? Because they never gave the younger ones opportunity to have a say in that kind of music. But because I came in so young, and I was doing so well, and my background like I said, prepared me for that great ahead of me. And I was close to Barrister too. I was learning seriously from him. So you can imagine putting all that together to other young folks, they see that great thing in me, to serve as a role model.

We are the mouthpiece of the people. We say the way the public feels about governance, either good or bad. I derive my followership from the students. We grew up together. I performed at various universities, colleges of education, polytechnics. And the youth on the street, those who probably didn’t even go to school. They see you as their spokesperson, because we say it straight as it is. We tell them what is not right. We tell them, “That thing that one said, he is lying, eh? He is lying. It is not true.” And they believe us. The activism in us really made us to be straight up like that, and be the voice of the people, the youth. We pass the message to people. [Sings] “Nigeria. Democracy. Government of the people, made by the people and for the people…” Things like that. It’s educating people about our responsibility to govern and responsibility of people us, the masses. We are asking questions. “Can we ever witness true democracy in our life?”

K1 says he paid a price for his outspokenness, especially during the 1980s military regime of Sani Abacha.

The worst time was in the ’80s. Very many arrests. Very many destabilizations of performances. They come to your venue. They don’t want to see you with your group. They don’t want to see your people greeting. Somewhere you have a particular performance spot, they come in there and close it down, deny the ownership their license. You know the many things they did to Fela? What they did to Fela, they did to us too.

We would keep on running here and there. They send us away from here, we go and regroup at another spot. We would go underground, and the show was still going on. We make albums, and we release them to the public, and they would say, “He’s still there. Still saying it.” At a certain point, they called us to negotiate. They would say, “O.K. What were you talking about?” “We were talking about the responsibility of the government to the people. Do it justly. Give people what they want. Who cares about what you stole? What we care about good education, good health care system, good roads, good transportation. The ability for people to do business without molestation and harassment.” Those are the things. Let there be an environment for people to demonstrate their love, showcase their talent, and let everybody be free. You in government, you know one thing for sure, when you do it, and you don’t do it good, you still have to come back to the people to give an account of what you did. Which is happening now. People now they are so wise. They can tell any government, No. It happens everywhere. Happens here. And it’s still happening.

Saheed Osupa (pronounced Oh-SHOO-pah), also considers himself the King of Fuji, because the grand old man of the music, Barrister, called him that some years back. That caused controversy, especially among fans. In any case, Osupa is a major force in the music, and interviewing him was a particular treat because he sang so much during our conversation. Much of that is heard in the “Lagos Roots” program.

My name is Saheed Akorede Babatunde Okunola [b. 1969]. My stage name is Saheed Osupa, the King of Fuji Music in general. Osupa means “moon.” So I can say that the moon is the king of the stars. Osupa is not really my name. It is my father’s name, because he too was a musician. He was one of the pioneers of fuji music. Because fuji music was originated from this local kind of music they call etiyeri. Etiyeri is part of the songs they sing for the egungun, the masquerade. Egungun, they do like a kind of entertainment. They use whips, just flogging people, you understand. Because they sing about what is happening secretly. They use it as a form of preaching morals. They caution people. If they see you doing something that is against the society secretly, they will start singing, “I saw someone yesterday sneaking, doing this, doing this. They should not do this. This is wrong.” They will sing it, entertaining people. At the same time they are using it to preach morals, cautioning people to abstain from doing wrong things.

So right from that, they now derived another kind of song called were[or ajiweere]. That were, mostly Islamic people do that kind of music. They use it to wake people up during the fasting period. They wake them up to observe their prayers, because you know, Muslim people eat during the midnight. They don’t eat anything till the evening again. So they use this music to wake them up. You see them moving around drums and everything.

Then in the late ’50s to early ’60s, that was when they changed were music to fuji music. Fuji was tagged that name by Alhaji Dr. Sikiru Ayinde Barrister, when he went to Japan. He just saw a sign post. They wrote “Fuji.” His intention was just to tell people that the music was all about faaji, about entertainment. Faaji and fuja means enjoyment and entertainment. That is the meaning of faaji and fuja in Yoruba. Barrister was thinking about how to abbreviate it. He doesn’t want to say faaji and he doesn’t want to say fuja. So when he saw that signpost in Japan, they wrote fuji. That’s when he changed it to fuji music.

I was born in the ghetto. I was brought up in the ghetto. I was trained in the ghetto. My parents broke up when I was 6 months old. I lived with my mother. She was the one that brought me up. She was the one that trained me. I didn’t really know much about my father. It was only when I became popular that people started telling me about my father, and then I went to him and asked him, and he told me all the stories of how fuji music generated from etiyere. And he told me a lot about himself before he died.

I started singing in 1983. I loved mixing up with my friends. So this guy was singing, he was a leader of a band of like five members. So I now joined them, I was doing the chorus and he was singing. So his parents told him that they didn’t want him to sing, that was when we as a leader that’s the way I started my music career.

So there was this man in our area that used to organize a competition. He would tell you that you must sing a new kind of lyrics that they have never heard before. So they will now bring the judges, and this one will know about Yusuf Olatunji, this one will know about another singer. All of them. If you are singing, they will be listening. If you sing any part of those people’s lyrics, you are out of the competition. I always came up as a winner, for 10 years.

So then I was thinking: what am I going to do that will make me unique, that will make the world know me? I don’t want to sing in English, because if I started singing in English, I would lose that flavor of that fuji music. So let me think of doing something exceptional. What have I not talked about? Let me talk about marriage. What have I not talked about? Let me talk about hard work. What have I not talked about? Let me talk about honesty. What have I not talked about? Let me talk about diligence. What have I not talked about? Let me talk about courage. If I am singing about courage, I tell them merits and demerits of being courageous. I tell them the merits and demerits of being honest. I tell him the merits and demerits of being faithful. I tell him the shortcomings of being in a marriage. I tell them.

I started doing what I believe that the past fuji artists have not done. I did three albums at a time. I did four albums at a time. About four or five years ago, I was performing like six times a day. Those six concerts, if you play them, they’re not related in any way. So that was when Barrister was surprised and he said, “What kind of human being is this?” Because he was the king of fuji music then. So he was now seeing me someone was doing far above what he has done. So we now come out and said, “O.K., let me crown this guy the King of Fuji music.” This now made controversy more. It was a serious problem then. A big fight. They started singing abusive things about me and writing rubbish about me and paper, using journalists against me and everything. But I kept doing my own thing in my own way, and I kept moving.

[Sings] “….Nigeria, my country… Be faithful and honest…”

What I’m saying is that the political godfather controls the government. So they should not say a political leader is not good. It is probably the fault of the godfathers. Because the political leader in Nigeria, in Africa, can only do what the political fathers instruct them to do. “I am the one who brought you to power, so anything I tell you you should do.” So that’s why most of them do wrong things. That’s what I’m telling people.

[Sings] “….Nigeria, it go better…”

“Nigeria will be O.K. Nigeria will be O.K.” You keep saying Nigeria is going to be O.K. Is it going to be O.K. in 1,000 years? When is it going to be O.K.? There is no political leader that has a good intention. Most of them that has good intention, they are not allowed to become the leader of this nation. There are people that decide the government of this nation. So if they know you’re going to do something that is good for the people, they don’t want you. They want people who will do something good for them. So that’s what I’m saying. And that’s what the song is all about.

Osupa has done some 40 albums now, as he says, on many topics. But we also learned that there is a variety of songs in fuji (and other styles) referred to as “lewd songs.” These are songs with racy, sometimes coded meanings. We didn’t find singers all that willing to share examples of this with us. But Osupa came up with a good one.

[Sings] What I sang there was: A pregnant woman that has a baby in her. They are twins. So the babies heard someone knocking. So if somebody is about to knock the door of the pregnant wife, you know what that means. So one said, “Here comes daddy.” And the other one said, “No, this is not how daddy knocks.” When the visitor came in, the other one said, “I told you it was Daddy.” The other one said, “No, it’s not Daddy. He’s going is going to drop something like yogurt for us to drink, if it’s Daddy.” So because the guy was using condom, he was unable to drop that yogurt the other one was expecting. Then the other one said, “O.K. I believe it’s not our daddy. That means our daddy is doing rubbish with some other woman. That is why another man is doing rubbish with our mother now. So I will tell daddy that he should not have extramarital affairs with another man’s wife, so someone else too will not have it with my mother.”

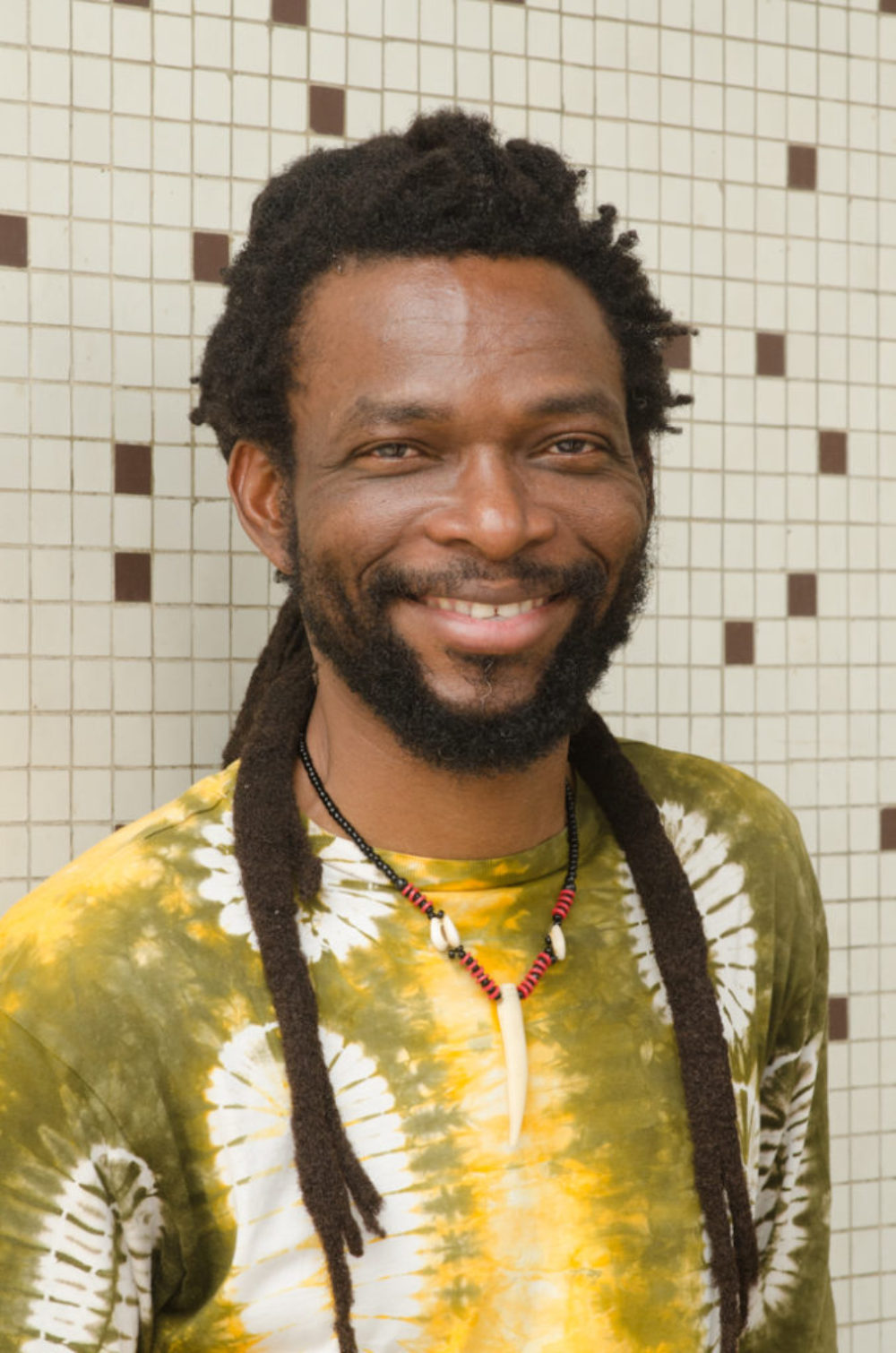

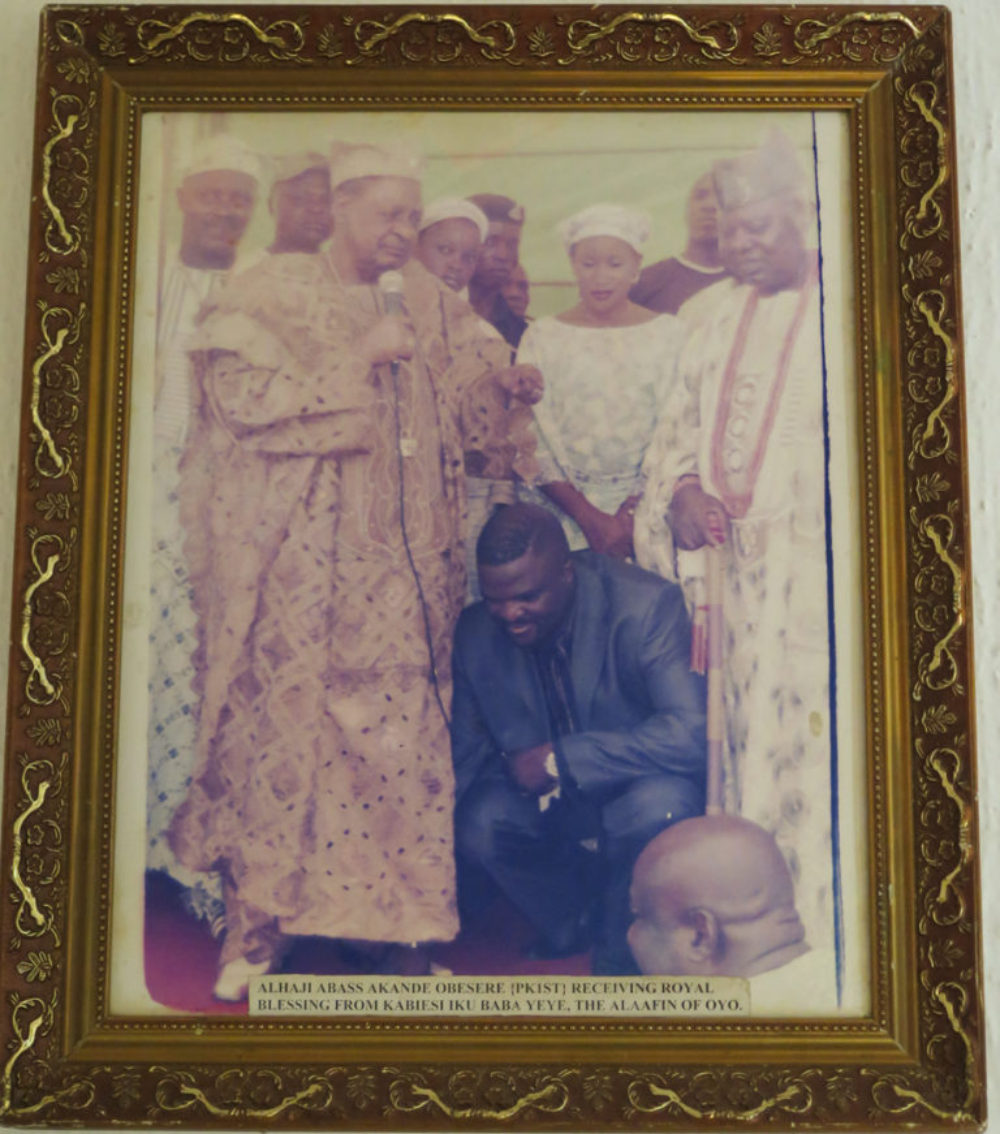

Obesere is another big star in fuji’s current generation. He is known as a playful, colorful, provocateur, a specialist in lewd songs, but also a moral leader. He embodies the paradox of fuji: moral advice and outrageous unbridled entertainment. Another larger-than-life fuji master!

My name is Abas Aponde Obesere, the Paramount King of music. I was born in Ibadan, and I come from a home of music. We played music in the family. You pick up a drum. So this music that I am playing is something that’s in the blood. And my kind of style is very unique. In Yoruba, people call my own style asakasa [pronounced ah-SHAH-kah-sha]. But at the same time, it’s not only asakasa that I can perform. I am a professional. I can play any kind of music that you want me to perform.

Fuji comes out of apala music. Who has been singing apala? Though most of them have died now. Like Alhaji Harouna Ishola, Alhaji Omowura. Olatunji Yusuf. Alhaji Tata Lualamu. This apala, that is what they sing. But fuji is not like that. It’s something that we modernized from that apala.

Asakasa means slang. You know, sometimes, you may not like someone close to the process to understand what you say. You can just say by slang. So the person will end up understanding what you mean. That’s what asakasa means. For example, there’s a Yoruba proverb that means you cannot say what you are selling is not what you are eating. Let’s say you are a burger seller now, because I know that’s what you can understand. You are a burger seller now. You can’t say you are selling burgers, but it’s not what you eat. You can never say what you are selling is not what you are eating. Or, another one says that anything can happen here, and people start saying, “Ah, what is it? Hey, we have not seen these kinds of things before.” You understand me? There is nothing that has never happened before. [Sings] It means, “You can continue eating fish, then I will continue sucking breasts.”

We asked Obesere about one of his early stage stunts, dressing as a woman on stage.

I did it to attract people. To attract more fans, to cross over. When they see you doing something funny, they will be forced to give you attention. You can’t say, am I putting on women’s dresses now? and not give the person attention. So you ask someone close to you, “Who is this?” And when they tell you, you know the person already.

Here in Nigeria, even our father, King Sunny Ade, you listen to all of his music, you will hear one out of it that is singing a lewd song. Even Obey, Commander, that has been singing spirituals. Even Sikuri Ayinde Barrister. Everyone of us, there is no way we are not going to sing that we are not going to do one or two things like that, because if you did not do it, will not enjoy you. It’s going to look boring!

Understand: My profession is different than the kind of person I am. You cannot judge my profession with my character. I am an entertainer. I was born to entertain. It doesn’t mean I should go with four wives or 10 wives. No. You understand me. So God structures everything for human beings in this life. That is why we can be invited anywhere that something good is going on, burial ceremony, wedding ceremony. Because it means they want you to sing about what they are doing, to praise him or her, talk of one or two things that people will feel, “Ah! This man is saying sense.” And if you are not into that kind of traditional music, you can only come and entertain, just for them to dance.

Salawa Abeni is the most prominent woman in fuji music. A veteran singer, composer and bandleader, she was a particular delight to meet. She sang for us, served brandy (though she didn’t drink it herself) and made us dance!

My name is Queen Salawa Etiome Alidu Abeni, and Her Waka Funky Modernizers. Waka is music all over the world. In Yoruba language, we call it ori. But in Hausa we call it waka. I am not the waka creator. I met old, old, old ones in the waka music industry. Everybody that sings music today in Nigeria, whether fuji, juju, Sakara, Apala, high life, hip-hop, in Nigeria, they are all singing waka. Waka is music.

We had some trouble pinning down exactly what distinguishes waka. Beautiful Nubia said, “Waka was a bit slower. And of course, because the women were doing it, there was more melody there. A lot of the fuji was based on rhythm. This was just one melody there, a lot of hand drums, shakers and voices, beautiful voices.”

We always played moonlight, in the moon. So we gathered ourselves together. We will join our hands together. Somebody will be in the middle, and be taking us one by one after they sing. Anybody that loves to do this music, they will be shouting.

There was a radio program then in 1974.The program started at 9 o’clock in the evening, so any time they are doing the program, I always go to the person who has a radio in my village to come and listen to the program. I used to listen to King Sunny Ade, Commander Ebenezer Obey, and Professor Haruna Ishola, then reproduce it, just singing and dancing. But I didn’t know that by the time I am singing it, God has witnessed me and said, “Amen.” That is how I started in 1974. In 1976, I made by one first album. It was titled In Memoriam, for our late general Murtala Mohammed. It sold like one million copies then.

I’m the first lady in the music industry in Nigeria. The type of music I am singing, when they are singing it, everybody is sitting down. But being a small girl, I said, “O.K., what am I going to use, the brain, to beat these people?” I stand up, and say everybody must stand up. We did my own music on standing. So I funkified by introducing piano, guitarists, and electric organ. That is the meaning of funkify.

I’m in early 20s, then, when Oba Lamidi crowned me Queen. Tears were running down my face because, you know, as a small girl, everything just happened like that. Thank God.

[Sings “Gentle Lady”] The meaning of “Gentle Lady.” When my children were young, I was driving them to the school one day, and this man hit me, hit my car. Instead of him to beg me, he was talking, blah blah blah…I’m telling them, “You will kill somebody.” He doesn’t have any money to pay. I’m just looking at him. And he is still saying, “You can’t do anything” And I said, “You know what? I am a gentle lady. I am not a fighter. Don’t push me to fight.” That is the meaning of “Gentle Lady.” I am a gentle lady. I am not a fighter. Don’t push me to fight.

I did that one “Experience” and “Gentle Lady” in 1990, followed by “Waka Carnival.” That is when Oba Lamidi crowned me Waka Queen. My name is Alawa Abiomi Abeni, and her waka group. When they crowned me Waka Queen in 1991, I changed it to Queen Salawa Abeni and the Waka Funky Modernizers. I introduced guitar, calabash, and the piano to funkify it. That’s why I call it “and her Waka Funky Modernizers.”

I sang a song in my past. [Sings] “I’m a singer, oh. I’m a dancer, oh…..” Then when when my son started music as hip-hop, we did a remix together. [Sings] “I’m a singer, oh. My son is a rapper, oh…..” It’s not message alone. But in my own music, as you are getting messages, there’s also danceable. That is where I’m coming from. I sang with Chief Commander Ebenezer Obey, we did “Omo Ogun Ise Ya” together. They gave it to me. I funkified, modernized. He did his own with his own beautiful voice. I did my own with my beautiful as a young girl. Yes! Sir Shina Peters is there. Adewale Ayuba is there. Shina Kone is there… The Islamic and the gospel. They put all of us together.

So that’s how I come: the only tiger that travels the beach. I am the only lady musician that troubles all male musicians. The young ones call me “Mama, mother of them all,” whether they like it or not!

Fuji remains very popular. Shows happen all over Lagos, generally not publicized widely. They’re often private events, weddings or other ceremonies. When there are public shows, people often find out just by word of mouth or social media. All that said, the music does have its critics and its limitations.

Beautiful Nubia: I don’t think there’s a fuji show you can go to where they won’t fight. They are always fighting. This is what happens. The musicians themselves are not poor at all. They get a lot of money. They have their own clientele who have a lot of money. A lot of them are like business people, traders and stuff, or people who do other things, and I think that sometimes why the fans do fight. Because the fans expect the artist not just to play for them but also to give them money. Fuji shows they will say they are charging a very small amount. People will fight to get in there. They get in there. They start fighting again. And the artists can’t get in because people want to take money from them; they want to extort from him. You can’t play the venue because you have to pay them. It’s always kind of like that.

Kunle Tejuosho (Proprietor of the Jazzhole, a great source of classic Nigerian music recordings): Fuji has lost a lot of its substance. Fuji then, late ’70s, ’80s, even K1 when he started, it was very creative rhythms, all kinds of funky rhythms. There was an innocence to what he was doing. He wasn’t copying his master [Barrister]. He had his own style, and he had his own crowd. And his crowd is still with him. But now, they are bringing in all kinds of instrumentation. That’s not fuji! You have to understand that the percussionists, the talking drummers, the sakara drummers, they are all from families. The guitar players are just there. They are not fitting in. They are not trained. They are just playing into rhythms. There’s no arrangement! Original fuji, there is an arrangement. They understand the lines.

Ade Bantu (leader of the band Bantu and organizer of the Afropolitan Vibes concert series at Freedom Park): Fuji music was always there. But you can only appreciate it if you speak Yoruba, or if you are really open-minded enough to say, “O.K., I don’t understand the language, but I love the beat.” I remember the first time I saw white people connect to fuji I was like, “But they don’t understand what they are singing.” You know? So that is when I had to shift my perspective. Because there are a lot of non-Yorubas in Nigeria would say, we don’t understand it. Well, we appreciate it, but…” Then you had exceptions. You had people like Shina Peters who completely blew up and cut across board. And then you had an Adewale Ayuba who maybe also had his moment. And you had K1, but no one that was consistent in terms of cutting across. Because even if K1 is big, it’s not like people in the north know him, or in the south, south. They know of him, but if you ask about the music, they can’t really tell you anything.

K1 de Ultimate: I have other businesses. When you make money, you have to put your money somewhere that keeps things going. I’m into electronics. I’ve been doing electronics for the past five years. I’ve been bringing equipment into Nigeria for the past five years. I buy from Long and McQuade in Toronto. I buy from New York. Very many places I buy equipment from. Sam Ash Music in New York know me very well. I have dealt with them in several hundreds of thousands of dollars. I bought equipment. I sell equipment to churches, and different organizations. I go to Sweden. I’m a direct secondhand distributor of Bang & Olufsen. So I have something to fall back on. I wouldn’t encourage anyone not to have a fallback. Music. No. Music is not enough when you have the kind of load that I have over my shoulders.

JUJU

One of the tricky aspects of fuji and juju is the way they are loosely identified with organized religions: Christianity and Islam. You hear a lot of juju/gospel on Lagos radio. Fuji is not explicitly associated with Islam these days, but you hear those roots in the vocal style with its intensity and ornamentation. And of course, behind all of this lie older African faiths and practices.

Mark LeVine (Hip Deep historian, UC Irvine): You kind of have Christianity and Islam facing off in Nigeria. But where’s all the variety of religious traditions in this country that have disappeared from public view? They’ve gone underground and I think that’s a disaster because these traditional religious practices and beliefs were part of communal structures that had been developed over centuries. These practitioners were first of all forced underground by colonialism and British rule, and then again once you had the Nigerian state. These were practices that encouraged decentralization, communal versus state power—all things that no government was going to want to encourage. Christianity and Islam each in their own way, represented “civilizing missions.” So people were constantly being berated by Christian leaders and also by Muslim leaders for any kind of traditional practices. This is something that Fela directly spoke against. He tried to bring the people back towards what he thought of as traditional Nigerian or African religious practices, more in tune with the earth which was being massively destroyed right at the time Fela became political in the ’70s. That’s when the oil took off and more and more was flowing and the environmental degradation really started to tick up. So it’s all very organically related.

Sir Shina Peters is one of the preeminent living juju artists. King Sunny Ade and Chief Commander Ebenezer Obey are the living patriarchs of the genre. Both are in their 70s now and perform only when it suits them. But Sir Shina, representing the next generation, continues to play steadily all over Nigeria and beyond. He made his mark in 1989 with his Afro-juju sound, defined in three key albums: Ace, Shinamania and Dancing Time. Sir Shina’s son Clarence Petersis perhaps the most sought-after music video producer in Nigeria, and he too comments in this section.

I’m sure it’s the church that influenced me to have passion for music. I started young, let me tell you. I bought my first car at 13. Had my first child at 14. My first house at 16. So before 20…

Banning: …you had seen it all. [Laughter]

Sir Shina: I wanted to play something that was totally different from what they had been hearing. Because the Igbos and the Hausa refused to accept Yoruba music. Because of the language, we cannot carry them a lot. So I said to myself, “I want to create something that will unify the country together.” That’s how Afro-juju started. That was the time the fuji people… May he so rest in perfect peace, Alhaji Sikiru Ayinde Barrister came with “Fuji Garbage.” And nobody wants to listen to juju music again. And I said to myself, “Continue this way with juju music, we die.”

Clarence: Juju and fuji percussions are now intertwined. But it wasn’t always so. Juju had always been more highlife. My father Shina Peters, he said one of his biggest contributions was a taboo. He took fuji percussions and brought them into juju. He did that for a reason, because fuji had the streets and he wanted to tap into that larger audience. He wanted the mass market. And there was a problem in the ’80s when he did it, it actually caused some issues for him. Juju music is usually very highlife and very slow, so when you start having [Sings fast fuji percussion], “Woah, woah. hold on.” But my father had been an apprentice under everyone… he started off with a juju band; at some point he moved to apala; he had been an apprentice under Fela for 10 months. For him to actually find what he called the Afro-juju sound, he had done about years of apprenticeship in all those different genres.

Sir Shina: It took me four years. I left everything. I said I want my own identity. I want to be known as a creator. I went to where Barrister is playing. I gather what people are enjoying is not the lyrics, it’s the percussion. Now, I went to a disco. I want to see what the students are enjoying in it. I can see that it is the heavy fives. [Sings]. Then I blended with jazz, African jazz, Fela’s type of music. Then I now add to my fast tempo aspect, and that is what killed the industry. By the time Ace came out, every artist, none of them can enter the studio for almost three years. Because they don’t know where to start from. They were used to, [Sings]. And now, [Sings]. So for any artist to go to studio, I mean they find it difficult.

Clarence: By 1998, he [Sir Shina] had hits back to back over a 10-year period. He had found the sound that could unite cultures: Hausa, Igbo, Yoruba. Everyone could actually tap into it, which is probably the recipe for what we have today. Now K1 also did that for the new generation. Fuji listeners could put a K1 tape in their car and pump the volume, on Victoria Island, and not feel inferior. That was what Wasiu [K1] did; he made them feel like, “My music isn’t inferior.” Instead of listening to it in corners, they could do that. Since K1, there has been a subconscious effort to make sure that fuji music never dies. It never experienced the drought in those five, eight years. So there has been continuity and consistency. Juju, on the other hand, didn’t have that consistency anymore. Fuji has evolved so much that it’s still around now, and juju just remained, in that classical era.

Sir Shina: You know, that boy, he’s a genius. The guy is from heaven. I appreciate Clarence. I admire his courage. We used to swim in that pool when he was like three years old. I knew that this guy is up to something. You watch Clarence’s job, totally different ideas from all these musical videos. He always liked to distance himself from what others are doing. Son, I love you so much.

I don’t know what happened to our government. Our government can generate all lot of foreign reserves from music, but they prefer football. They vote for football. Millions of dollars. I told them that what you did for football you can also do it for music. Give them the best studios. The best theater. The best joints.

Our neighbor governor did something last Christmas. He organized a festival. It was the first time that the crime rate was at the lowest. You know why? Because all these different people were busy watching artists for almost two weeks. Even if you want to go and rob, you would like to watch Shina Peters at the stadium. Music is something that the government can use. It’s the fastest language that you can use to send your message across. There is no way you can kill music. Because even the kidnappers and the armed robbers too. They listen to music. So why can’t we use that to eradicate the crime? Let’s now allow our people to see us as godsends, by playing good music, giving them advice, and let the tension die, and that is exactly what we are cooking.

Ayo Balogun is the Queen of Juju music. When we interviewed her in her office, she told us she got her start in the church. Recognizing her exceptional voice, members of the congregation invited her to perform at events, and eventually urged her to form a juju band. She’s never looked back.

I went to a school of music here in Nigeria. I took correspondence exams from London Royal School of Music. I actually was planning to be a music teacher. Until this fateful day and my friend said, “Oh, we know that you go out with your church to perform every time. And I know you can do this at our party.” And I said, “O.K., let me just do this for a friend.” And when I got there, the reception was so overwhelming. The acceptance was really beautiful. And people started asking me for my complementary card, which I did not have at that time. So I started writing my landline number that I had for them. I wrote the numbers for them, and people kept calling me. That was 1995.

I was not really, really good with juju music then. I did more of gospel music. I started learning after that by listening to the works of other juju musicians that have been before me. People like Ebenezer Obey, King Sunny Ade, Dele Abiodun, I.K. Dairo, even Shina Peters. Juju music is a very difficult type of music. Because it is percussion and singing. It involves a lot of equipment, the guitars, the maracas, omele, gungun, all sort of instruments. So it was very challenging then. But I love challenges. People are doing this; why can’t I?

Interestingly, the top people prefer to listen to juju music at their functions. Because juju music is very, very clean. It is more meaningful. We sing to correct things that are going around in the society. So that attracts intellectuals. Gospel and juju, they are kind of interwoven. Hardly can you find a juju artist who will not praise God, who will not do gospel. Juju artists, most of them are Christians. And fuji artists, most of them are Muslims. Maybe that’s where the inspiration comes from.

The way fuji is sung, it’s like they are reciting the Koran. That’s the way it sounds. Juju music is a straightforward thing, no Arabic sound like of lyrics. That makes us totally different. But, seriously, it can never take the shine off juju music. It can never take it, because the difference is there. The difference is there.

When I am performing, inspiration comes. You can use any of these older songs while you are on stage. I have some albums I recorded where I take songs from those. I have five albums now. When I’m playing live music, I can do all sorts of brands of music, even gospel music. Everything. But I do write songs. I write songs a lot. I am a songwriter, a composer. [Sings] “Whatever you do today is a story tomorrow. Whatever you do today is a story tomorrow. So do your best. God will do the rest. Do your part God will do you right. Do your best. God will do the rest. Do your part. God will do you right.”

Talking of the women in the industry, we have Titi Ogun Toyibo, Princess Folake, Tope Tenten, Seun Aranisiola. Who else? We have Tywo, another very good lady. But I don’t have any women in my band. I am the only woman. Why I do not want women in my band is that I wouldn’t want to limit anybody. Maybe I would be working with someone and she will say, “Oh, I want to go and get married.” Sometimes maybe she is sick sometime. Maybe she is pregnant. At the end of the day, she will not be able to cope with the very tight schedule. And you don’t want to ruin her home anyway, so you have to actually let her go. So at a point I just said, “You know what? I don’t want to do this anymore. No more women in my band.” Maybe I’m lucky because I started at a time I was very matured. This year I will be 60 years old. I don’t have anything to keep me down, and the children are grown up.

I sing mostly in Yoruba. For my non-Yoruba audience. I mix in a little bit of English.

Joseph Alabi (leader of the multigenre percussion and vocal troupe Kiniso Koncept): I don’t know how those songs became segregated to just the Yorubas, because the juju was an inception from the Salvation Army church. The young altar boys at Salvation Army, they used to play the maracas. So it was them saying “ju sí mî kin ju sí e.” “Throw the maracas to me, and then let me throw it to you.” So the song is just going on, maybe praise and worshipping song in church, and then they keep playing the maracas. Someone plays a little and then tosses it to you and then you play. That act is called ju sí mî kin ju sí e And that was how ju sí mî kin ju sí e became juju. So Salvation Army is not just a Nigerian church. Salvation Army is not even Nigerian. But along the line it became really segregated and it became a Yoruba thing.

Timmy Wonder is the youngest juju musician we met, a true believer in the genre. We met him at his rehearsal space and recorded him working with his band the Creative Crew. We also saw him performing at a memorial service for an eminent Nigerian, a large catered event at a Lagos hotel. Both time, Timmy showed impressive energy and verve. As he insists, juju is not dead!

They call me MP Timmy Wonder, Mr. Creativity. Because I am most creative with everything I do. So the name of my crew is the Creative Crew. We are addicted to creativity. We are always addicted to creativity. When people ask me what kind of music we play, I will tell them I sing juju gospel classical.

I was born in Lagos here but I hail from Edo State. My dad and my mom are from Edo State. When I was in primary school then, my dad didn’t want me to be singing. “You have to go to school. You have to eat. You have to read.” But when I was in school, I could feel this inspiration. I think that’s from God Almighty. In school, maybe after our lectures in school, from my secondary school, I created a crew then, just five guys. We had the long break, we stayed back in the classroom. That was time to play on the desks. We would sing and move. There might be four or five of us hitting desks or some tin cans, just playing.

After school hours, I was in the junior choir in church. I love going to church because of the singing. I am very small boy then. In time, they can see my ability, the way I sing, and they can see an inspiration to me. “This guy has a better future.” Then they promoted me to the senior choir, where I played the drums. Then, little by little, I started getting into the music. They taught us music; they wrote the music on the board like this, but they would want to sing the music offhand. The rest of my friends than were in the junior choir, they don’t have the ability to sing offhand. They must hold the paper like this. But me, and this is a gift from Almighty God, I sing offhand. So they promoted me to the senior choir. I was at home one day and something came to me: why can’t I create a group? So I find I have the power or ability to create my band. We’re just five guys, but we created our group.

You know, people think juju music is dead. Juju music is not dead. Juju music is alive. We have an association here in Nigeria called AJUMN. Association of Juju Musicians of Nigeria. Our president in Nigeria now in juju music is Queen Ayo Balogun. She sings King Sunny Ade style. We have juju in different states. We have them in Ijebu, We have them in Ogun State. We have them in Edo State, in Ibadan, in Abuja. Just go out on Friday, any Friday you chance. I’ll take you around and you could see a lot of juju artists performing every Friday, painting the town red in Lagos state!

JUJU, FUJI, HIP-HOP

We asked various roots artists how they feel about the new pop music of Nigeria, which has taken the continent by storm in recent years. Lagos music industry insiders like to call the music Naija pop. Folks in the diaspora tend to call it Afrobeats. But many in Lagos, including those quoted here, use the term hip-hop.

Queen Ayo Balogun: I will first of all give kudos to Nigerian musicians. The industry is getting bigger every day. Seriously. They are doing quite well. There is nowhere I will go to and I will not hear Nigerian music, even at the stores in the United States, I will hear our hip-hop and Naija pop kind of music. But how it has affected the juju musicians. Now people want to have juju music at their functions, and at the same time, they want the pop music. So sometimes, it cuts the duration of time we perform. It cuts it short. Because after we finished performing, then they will start to play the pop music.

Timmy Wonder: Hip-hop now…. They don’t really work the way we do. When I go to the studio to record my album, we play all the instruments, all the percussion. We use the analog studio. We’re doing everything live. I’m there with my producer with them doing everything, which hip-hop would never do. They will just go to the studio, and just create a beat for them [Sings] on the keyboard. They just start singing. And they are blessed by God Almighty. When you invite me to perform live now, I’m playing everything live, but hip-hop would never do that. They just bring the CD, stuff in the CD, and start miming.

When the hip-hop came out, it really affected juju world. I will never lie to you. I just have to be blunt this time around. It really affected our world. The hip-hop! And most of all these hip-hop artists, what they sing, they take it from juju music. Listen to most of their songs, their lyrics. It’s from juju music. They just start adding rap to it, and people start buying it. [[Sings and raps]. And people start buying it.

Saheed Osupa: Nigerian hip-hop is an extract of fuji music. They just extract one of the lyrics and start repeating it, like a kind of chorus. Instead me doing all this long play, 15 minutes, they just do three minutes, two minutes.

Clarence Peters: That’s where the dispute’s always been. You’d say it’s more fuji than anything, and then juju people would come and tell you it’s more juju than anything. But understand one thing. It sounds like it’s more fuji to them, because of the fact that fuji was catered to the grass roots, and juju catered to the aristocratic. So when you listen to street music, it sounds more fuji. However when you listen to people who actually try to apply more education to it, just more arrangement and all that, just a lot calmer, so you can feel the chords more, it begins to move towards juju.

The difference between fuji and juju, there’s a huge, there’s a lot of history behind that. There’s a lot of beef within fuji, within juju. For instance I was having a conversation with Pasuma the other day, and I was kinda amazed the way he broke down the fuji history for me, from the ’80s till now. Kollington and Barrister pretty much took the music to a certain point, but the aristocratic market in Nigeria did not want to associate themselves with fuji, because it was seen to be “local.” Juju was more aristocratic. It took Kwam 1, Wasiu, to actually flip the music, because between ’88 and ’94 fuji music actually had a huge decline. Kwam 1 is the father of the new fuji music.

Kunle Tejuosho: There’s something hypnotic about fuji. And guys like Wizkid, hey, these are street boys, they are fluent with the language, they are strong with the language, and they’ve managed to use fuji slang and style and rhythm and infused it into their brand of Lagos hip-hop. And they’ve cut into middle-class kids. You know, they’ve got all our kids mad with the music

If you’re talking about music in Nigeria, highlife is highlife, juju is juju, apala, sakara, and all the other forms. They all had their own forms, and their own style and their own audience. These days what we should ask ourselves is, “What is the Nigerian sound? What is Nigerian music?” Then I get worried, because if we’re going to take his young, exciting music that we are talking about now. It’s a mixup of all kinds of things. I still find them searching. They are young. Very few of them will remain, because there is a lot of money that they are making. And most of them are in there for the money and less of the music. I know that for a fact. Even from their lyrics, you can tell that it’s a money thing. I don’t know if it’s going to evolve, because I mean it’s just about beats. It’s not as if they are thinking about arrangements or how they are going to tap from this and tap from that, like a Fela was thinking of tapping from all these forms. I just think it’s a thing of the times.

K1 de Ultimate: We have two sides of society. We have the children of the rich, famous, powerful people. Then you have children of the struggling families. If there’s a musical concert, and the artist came aboard to sing about happenings in the land, to complain, a young guy left school in the last three years could not have a placement at any job–they are roaming the street. Definitely they will welcome such an artist. They will see that artist as feeling the way they are feeling. They will follow. But the children of the famous and rich, they will tell you, “We don’t like this. It’s a commonly known thing. Every society has that.”

Today everybody wants to get rich quick. If you are hard in going against the government, definitely you might not be making money. The present-day musician, they see the importance of people coming in to sponsor them. And who are those people behind all those different organizations sponsoring artists? They are the so-called people in government. The money they stole from government to pump into various organizations, and they think they can silence you. “If you want me to sponsor you, you don’t say what you’re saying, you don’t let your focus be attacks on government today, and stuff, and stuff.” But we are made already. It’s part of us. If I want today to declare a serious war on government, war comes. Because we know them. We see them every time. After music, we sit together. We wine and dine. We discuss issues. We argue. We are used to that.

But I must be honest with you. I would not do that for the whole night. You dedicate a little time to say, “This is what I want to talk about.” And when you talk about that, those who feel good about it, they will applaud. They will definitely know where you stand. We know you stand on the side of the people.

Related Audio Programs