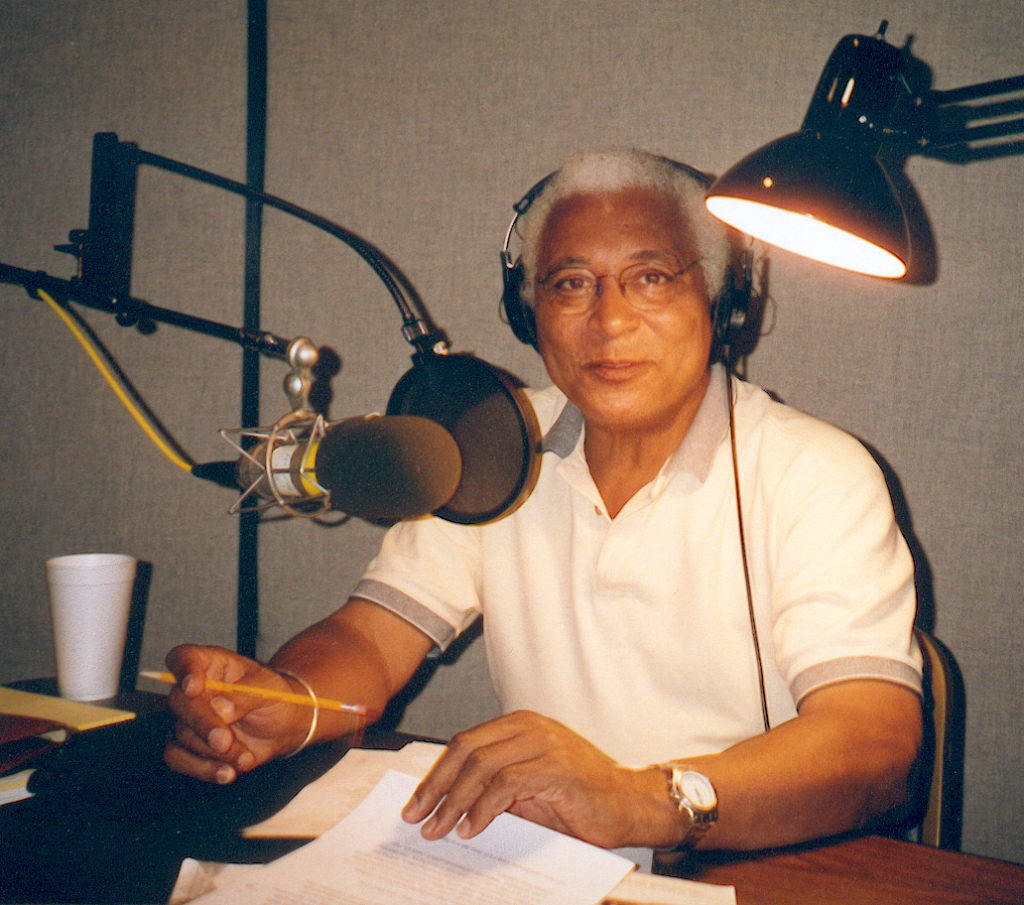

Georges Collinet has been the host of Afropop Worldwide since the show first aired in October 1988. In 2015, he celebrated 50 years in broadcasting. Producer Banning Eyre interviewed Georges in his Washington, D.C. home studio on Sept. 30, 2016. It was the night after Afropop supporters had gathered to honor Georges as part of our Icons and Innovators event. Banning was also in the process of writing a retrospective program, “African Music at the Crossroads.” The two Afropop veterans engaged in a freewheeling discussion. Here is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Banning Eyre: You were honored as an icon last night. How does that feel?

Georges Collinet: Icon. That feels old. Like the Virgin Mary in Russia, in a gold case…

You used your time at the mic to thank certain people. Give us a taste of that.

Well, I started with my parents. My mother was the woman who carried me for nine months and who gave birth to this guy, and transferred her genes, that were very joyous and loved music and happiness and all that. And then my father, who was this French guy who was very stern, and also, he was a trickster, which I am too.

That's where you got it.

Yeah, that's where I got it. But he gave me that structure that led me not to be a ruffian, which I could've been.

You have the right stuff to be a ruffian?

I had the right opportunities.

Georges receives Icon award (Ben Bangoura)

Georges receives Icon award (Ben Bangoura)

You were born in Cameroon.

Yes, I was born in a small village. It's really just a hospital in the middle of the bush, in the forest. There was an American hospital in Metete, the only medical facility around. But it was over 100 km from my village, and to travel that distance-- Jesus, it took forever. My mother had her child, a girl, and she gave birth in the forest, but she died at birth, and when I came along, my father said, “I'm not taking any chances. You go to Matete.” So they arranged a tipoi, two bicycles put side by side. And you put a piece of wood to make a frame, and between the two pieces of wood, you make a bed, and there are four or five strong people pushing these bicycles on the road.

That's how you made your first road trip?

Yah, mon.

What big town are we near?

The biggest one is Sangmelima [in the south, nearer to Yaounde than Douala]. It was a city created by my father. The presence of the white man made a difference; a lot of people came there. At the time he had come out of the Navy. He had fought in Sebastopol and the Crimean War and then came to Africa where he was dealing in buying cocoa from village to village. Because it's a cocoa region. They were buying the cocoa and selling it to Europe. This was 1925, '30—somewhere there. It must've been extraordinary. I wish I could've interviewed him more, and interviewed some of the elders in the village, to tell me how life was. It's all coming out in the book.

You're writing a book. After 50 years in broadcasting.

Yes. I started in 1965.

So we’re now in the second year of celebration.

You know, radio is such a magical media. I just love it. I do forays into documentaries for television and film, but nothing really compares to radio.

Well, you have lived the Golden Age of radio, both there and here.

My God, I was very lucky. Because it was the Cold War. I was brand-new in America, and this gentleman who was in New York who was a correspondent for the Voice of America at the U.N. His name was K. Watson, Kenneth Watson He was a Russian guy, but you know what the time, everybody took an English name. Oh, Kenneth Lawson would do.

Did his accent give him away?

Oh no. This guy had a voice that was just fabulous. I went to pass the test there because I didn't have a job. I was selling socks at B. Altman, this big department store across the street from the Empire State building. And then I went to the French embassy, the cultural center, and somehow, they had me read books. I had piles and piles of books to read for university workshop.

Like books on tape before their time.

Yeah, tape, and they would send the tapes to universities for their language laboratories, to teach French. You had to have the right accent. And it was funny. The guy says, "You're the only person who really sounds French, and you're black." I said, “So?” But anyway, reading all these books day in and day out--I think that's where I really learned my job well.

Anyway, then I came to Washington, and there was Terry DeRosa who was the chief producer. And Terry became like my mother. She wanted me to be the best in radio. “You have the talent. I want you to be the best.”

This is at VOA. Voice of America.

Yes, VOA. From New York now, I'm in Washington, D.C., where toilets still had signs, with silhouettes for black or white. The funny thing is, the black people would never, never, go into the white toilets. And I didn't know, so I went anywhere. Everybody say, "You're going in there? It's for white people." I said, "What do you mean it’s for white people? Don't they do what I do? Come on, give me a break”

So Terry would take me in the studio for days. She would give me a book, a script, in French, and I was reading this paragraph over and over, sometimes for half an hour, sometimes 45 minutes, until she was satisfied. Sounds like Afropop doesn't it?

I was going to say...

Georges with VOA compadres

Anyway, the talent of this woman was amazing. We used to do stories, big epics, where I would do many voices, and they would put in music. Mostly about the American Revolution, in French. “And George Washington says, "Je veux traverser le Delaware. Allez-y, mes enfants.” And the music swells… I love that, you know? I really love that.

That's how it started. And Terry taught me how to edit. You had a razor blade, and your little slate where you would cut. You would mark first where to cut, then you would put it on the thing and cut it. But you know, I was doing a lot of pranks at the Voice of America…

Pranks? You?

Oh, my God. You can't believe it. It was terrible. You know those tape rolls? We would see who could throw them the furthest. And so we had these tapes rolling down the corridors of the Voice of America sometimes. Sometimes visitors would see these things going by and say to the people who are taking them around, "What is this?" And they would say, "Oh, it must be Georges Collinet.”

But it was amazing how many cuts we did. They didn't want any ums or ahs. It was so bad with this need to remove all these things that one of the editors cut all the clicks out of Miriam Makeba’s "Click Song." “Did you hear that?” Yeah, it's part of the song. “No. Remove it.” No, you can't to do it. That's their language. What's the matter with you? They removed all the clicks in the "Click Song."

Miriam Makeba

Interesting. Because Miriam Makeba was one of the first African artists to get on American radio. People didn't really know what this music was all about.

Yes. Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela, in the mid '60s.

What was your own experience of African music before that. What was its role in your early life?

Well, I have one friend, and we used to go around, and I sang. I had a guitar, and I was a singer. And we used to go down from Paris to the Cote D’Azure to Nice, and we would stop at various places and I would sing. We would panhandle, and we made a lot of money, man. Sometimes we get Fr.100,000. That's $400. And people would say, "Would you come and play for us at this event?” And my friend had a scooter. I was sitting in the back, and we would ride all the way down that way. We had a lot of fun. A lot of fun. We all had a good time.

So I was singing a lot, to a point where they wanted me to sing at this big gala in Nice. And they had a poster” “blah, blah, blah, blah, and Georges Collinet.” So somebody passes by and sees this, and sends a letter—because we didn't have a telephone then—to my father in Africa, saying, "I saw the name of your son on a billboard. Can you believe that?" About a week later I see my father and he’s saying, "What is it? What did I hear? You're doing what?" "No, Papa, no. I was on vacation."

That wasn't his dream for you.

No. You know, it’s the familiar story. The familiar story.

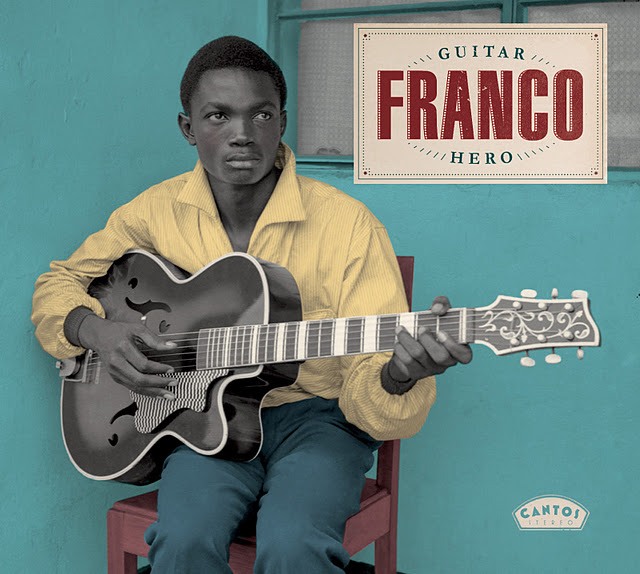

So you were singing French and English songs at that point. But what about African music? It was being recorded then. Franco had started in 1956.

But it was not reaching Europe. It was very local. At that time, we used to listen to jazz a lot. And to American stuff. The Platters. "I'm so young, and you're so old, my darling." All the American pop stuff. But really, African music? Well, Francis Bebey was kind of getting there. But that's about it.

So when did African music start to really reach you?

When I came to America. But the thing is, Africa has always been there. My village has always been in my heart. My uncle was an amazing musician. He was the party maker. He used to build huge fires, and he would take his bandoneon, which was a small accordion, and the drummers would come, and man, the drumming. The drumming!. People think they’ve heard drumming here. Drumming over there in the village. Woah. It was, man, awesome. A lot of the people that I meet who remember say, "Man, you made us dream of Africa with your African tales, talking about your village, talking about your family.”

But when I came to the Voice of America in ‘65, I thought it was important for me to broadcast also a segment of African and Latin American music. Because the show was one hour every day. “Le Maxi Voom Voom with Georges Collinet.” [Sings "A Taste of Honey”] I don't know how much money the Voice of America owes Herb Alpert. It was called “Bonjour L’Afrique.”

Anyway, I had 40 minutes of American music, blues primarily, black music. soul and things like that. You know, at the time, it was so bad, that I would bring 45 RPM – one of those tiny 7-inch records. The were usually marked “race music.”

Right. They still used that term.

And I would give one of those 45s to the engineers, and they would touch as if it was dirt. It was amazing. I would say, "What's wrong with you?" “Nothing. Don't worry about it.” The mere fact that it was a 45 connoted race music, and they hated it.

Wow.

Anyway, I had 40 minutes of American music, and then 20 minutes of Latin and African music, because I thought people had to know about this music. I understood that in Africa, people did not really connote music outside of the music of their country. You know, the radio in Ouagadougou would only play the music from Upper Volta, Burkina Faso today. Or in Cameroon, people only played Cameroon music. So I had this thing where I really wanted people to hear the music." Decca Records was helping me with that. Because look around at all this stuff. Most of these 45s here are all Decca records.

They were a company that was really trying to make a business of recording and selling African music.

Oh, did they make a business! In those days African musicians would just take a tape recorder, a cassette machine, they would have the band, and they would put the machine here, and they would record, and they would send the tape to Decca, and Decca would make a record out of it, 45s primarily. But you know, they had so many of them that they were making a lot of money. I mean, how much did it cost to take a cassette to a record and sell it. So that's how it worked. Even Tabu Ley in the beginning, and Franco, it was really rough. The sound.

So because you had the segment on your show, Decca was sending you music, and this is how your first heard people like Tabu Ley.

Exactly, and I loved it! Like this show we did recently on the music from Bobo Dioulasso.

"Off the Beaten Track."

Yes. I have them all here. Volta Jazz. All that stuff.

So you recognized right away when you heard this music that this was new and exciting and it had to be heard. What are some of the ones that you still have to listen to every so often?

Oh, Franco. Sorry, Tabu Ley. Tabu Ley is my big buddy. Franco was my big buddy also.

They are looking down from heaven. “The two wings of the airplane,” as Tabu Ley once described it to me.

[Laughs] And Papa Wemba. I saw Papa Wemba when he was just starting, at a stadium. He was this guy who hardly spoke. But there were so many people. Sosoliso. Trio Madjesi, and the people in Cameroon where you had all the bikutsi people that were playing. Various obscure groups that were doing some incredible music. And Fanta Damba in Mali. Gee whiz. The Rail Band. Buffet Hotel de la Gare. And Super Etoile in Senegal. The sound was not the best, but the energy! You could feel the energy and all that.

Let’s talk about the energy that the music, especially made in the '60s and early '70s, had. This is coming soon after independence for most of these countries. How much did that have to do with that optimistic feeling that came with independence, that sense of starting a new future?

Well, there was a spirit there that was magical. It was independence, yes. But it was a happy music even before the independence. These guys were creating something. It was a movement that was so exciting. Yes, everybody was feeling liberated, quote unquote.

It seemed like it at the time anyway.

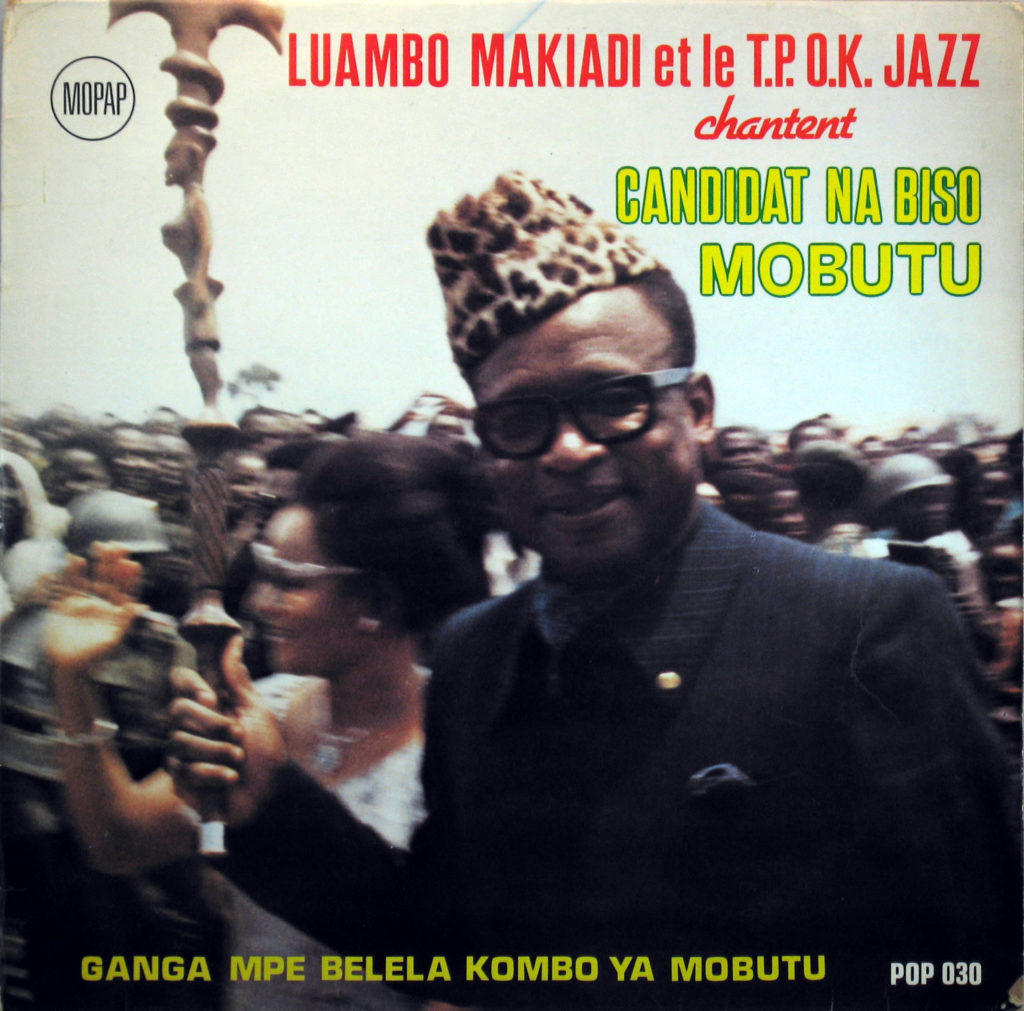

Yeah, at the time. But you know, a guy like Mobutu Sese Seko. He was terrible president of Zaire, but he was my buddy.

You knew him.

Oh yeah, I knew him very well. A lot of those leaders, they all used to wear the same glasses that I wore, you know those big heavy black-rimmed glasses. Every time they went somewhere, I was invited. Mobutu in particular, I have to say, he understood the power of his music and musicians. Sure, it served his purpose, but also he was giving them the chance to improve, to create. He was financing a lot of the bands. And in Mali, there were all these greats contests from region to region.

The Biennales.

The Biennale, yes. And the same thing with Sekou Toure in Guinea.

It's interesting, that paradox of these guys. You look at the authoritarian politics and the brutality they were responsible for, and then the fact that they understood the power of music. It's not all the leaders who had that insight. But it leaves a real mark today, because of the music that was created in that time.

Absolutely. Enduring music.

Let me ask you this. Because you were very familiar with African-American music at that time, and then you followed the emergence of modern African music. As you know, when large numbers of African musicians and bands started come to the U.S. in the '80s and '90s, one of the common experiences they had was that they would come before an audience in New York or Washington and it have an enthusiastic crowd dancing, loving something new and exciting, and that crowd would be also entirely white. And they would say, “Where are all the black people? Where are the African-Americans?”

The thing is African-Americans were stuck in their ghetto. It's much better now. But for a long time, and until very recently, they were stuck in a ghetto. They were listening to only black American music. That's all they wanted to know. A funny thing that happened to me. I was trying to promote African music, so I put together a program and I took it to high schools around, for the kids to listen to African music.

This was back in the '70s?

Something like that, and it was primarily in New York and Ohio. And I went there with my little tape, and my boombox, and I would play them the music, and the black kids would hide, because they didn't want their friends to listen to something so foreign. It kind of belittled them.

They were sending me little notes saying, "Please, don't do that again. All my friends are making fun of me. They think I'm a savage." But others would say, mostly the white kids, they would say, "Thank you, Georges, for bringing this into town." One of the letters said, "I thought Africa was not funner. I listen to you. And it is very nice. I'm telling my parents, next time we go on vacation, we should go to Africa." Because to them it was so different.

Interesting, but you say the black kids tended to feel uncomfortable.

Very uncomfortable. Part of that is just the idea of Africa. And not necessarily even the music. It was just the idea.

But I'll throw this out. When you talk about the happiness and the pride and the feeling of independence in African music, African music is so much about celebrating heritage. This is where we came from. This is where we are going. There's this sense of continuity that makes it happy. Whereas African-American music has more of a sense of solidarity among the marginalized. You talked about the ghetto, a sense of rebellion. It's a very different place to be coming from emotionally. Do you think that has anything to do with it?

To me, Americans wanted to keep a distance from anything that was outside their community. And I understand why. Because the other day I visited the African-American Museum. And I went into the basement where they have the slave trade. People asked, me, “What did you feel, Georges?”

You know I felt like someone had thrown me in a boxing ring with Muhammad Ali, because every time, I’d feel that punch in the stomach. Every picture that I saw was like being in a ring, and being punched out. It hit me so hard. God knows, I produced a film on slavery for UNESCO, for the communication of the slave trade, the official film.

So it's not like you haven't thought about that history.

No. But to see it. It's coming all the time, pam, bam, bam. All these little details. You know in a film, you just make it global. You don't go into details. Here, you go into details. It's like being punched in the stomach, or in the face. Because it is so strong. And so, for these African-Americans, they've been there for so many years. Four hundred years. The cruelty was so much that it changed the DNA of a lot of these people. The DNA. Can you imagine that? That's how strong the cruelty was.

I've heard it said that for all the physical brutality of slavery, the greatest harm was taking people's culture away. That to me is a big difference when you talk about popular music in Africa as opposed to America. In Africa, we're celebrating culture. In America we’re basically creating a new culture because the old one has been obscured or lost or disconnected.

Georges and Sean Barlow in early days of Afropop Worldwide

Georges and Sean Barlow in early days of Afropop Worldwide

But you know, it's like in the book I'm writing, one of the chapters ends when I came to Washington, D.C. Aside from the village, all my peers had been white. I lived with white people, so my vision was different, and I wanted to have the experience of blackness. So I moved to a place on Euclid Street here. It was totally black, and it was rough. I was talking about all sorts of things. “Did you hear that we walked on the moon? Blah blah blah.” And this guy says, "Do you really believe in that bullshit? What's wrong with you. Get out of here." And as I left, I saw two rats fighting on the sidewalk. That's the end of one chapter.

Now you have this wave of people going to check their DNA, to find out where they came from.

This is a new thing, that it's possible to do that, but also that people are interested.

Yes, they’re interested. And that’s where we, Afropop, should come in. Because people are saying, "I'm coming from Cameroon. I want to know more about this. I'm open. I can listen to music." Because through music, you learn about your heritage.

I did an interview last week with Rab Bakari, a Ghanaian-American who was involved in the early days of hip-hop and later went to Ghana in the mid-'90s and played a big role in the creation of hiplife music. These days he is working to get African music played on black American radio. He talks about the barbecue test. A backyard barbecue in Atlanta. They've got Chris Brown, and Sean Paul from Jamaica, and now he wants them to add Wizkid from Nigeria in the mix. You get the idea.

Rab says that language doesn’t count as much as it used to. It’s all about beat and groove, and music is moving from place to place much more easily than in the past. What’s your experience of all this?

My experience is very simple. In Africa, they love jazz, they love blues, they love pop music. American music. They don't understand a damn thing that these guys are singing, they just like the mood. This was perhaps helped by the fact that America was lucky enough to have Hollywood that promoted an image, and that image is very important. Like when I was doing my show on the Voice of America, people would say, "Oh my God, you are in America. Wow." When I used to do my show on Radio Luxembourg in France, people would call in and say, you sound American. Because my French, after having lived in America for so long, had changed a little.

But you know, one time I was with Dick Gregory. I filmed him in Gabon, and he was summing it up in an interview. He said, "When I was growing up, Africa was a bunch of savages, doing nothing, killing animals, eating crap." So many Americans still don't have an accurate image. We’re trying to create that with Afropop.

Right. We’re working on it.

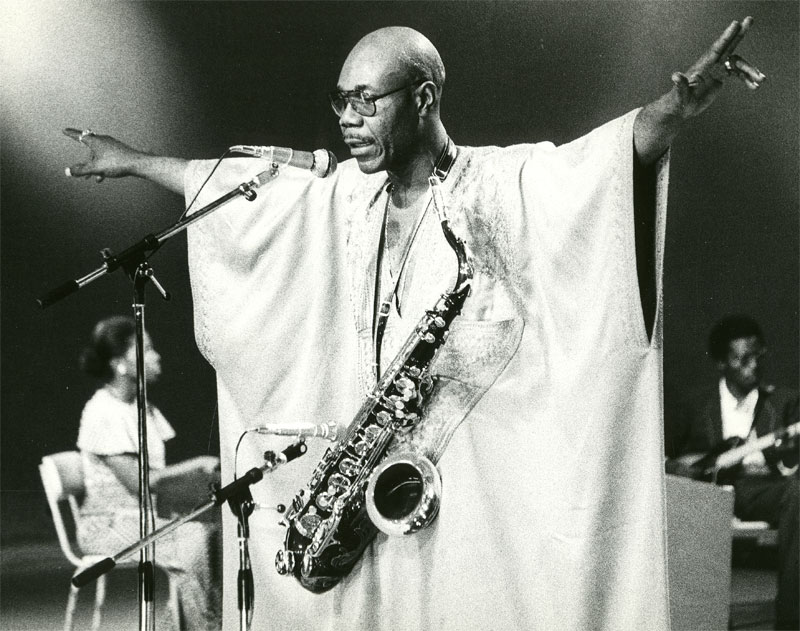

But that's a hard, hard long way. We have to create that image for people to really understand, to really listen to African songs. I remember discussing this with Manu Dibango, when we were together. He was saying, “I think we need the Bob Marley of Africa."

I’ve heard that before.

Yeah. But I think it's more than that; it's more than that. We have the Bob Marleys. Lots of them, starting with Miriam Makeba, continuing with Hugh Masekela, Youssou N’Dour, Angelique Kidjo… I mean they are there. But somehow, you have to put that sound in people's ears. Your friend is right. You have to put it in people's ears. How do you do that?

Slowly but surely. I feel like it's starting to happen. But when I listen to this new music, its identity is evolving, but it is a lot more imitative of American music, which cuts both ways. It may help with the backyard barbecue, but it may sound less interesting and original to a lot of our listeners, who are looking for something more identifiably African. But I want to go back to what you were saying about Hollywood images. Because most of these new Afrobeats songs come with videos, and the videos are always mansions, beautiful clothes, guys with beautiful girls, fancy cars. There is an image that this music is projecting for Africans within Africa, and this is help to make people in Nairobi listen to music from Lagos and Accra. What do you think about that?

Well, the thing is, it's a little too much. To me, it's really too much. It's always the same. The guy is leaning on a Mercedes and he has his beautiful lady next to him. It's not original. I mean, it’s what we used to do here in the ‘80s or ‘90s. We need to come up with something that really has the African stamp on it. Because, actually, that's what's killing African television. These producers that are trying to do some good television, and suddenly they end up playing only those winding butts of beautiful ladies. We have to come up with something original. And we are not.

But it's selling. Those artists are making good money, more money then those great artists we came up with made.

Like Prince Nico Mbarga. I always remember. He was almost crying when I met him. He said, "Man, you know, I put out 100,000 records. By the time it came out, there were 500,000 pirate copies in the market.”

Right, and his song “Sweet Mother” was one of the biggest hits ever.

But he didn’t make much from it.

We've talked about the piracy problem on our show a lot. But I feel like in a funny way, the piracy phenomenon inoculated African musicians for the shock of the digital age. Now few people pay for music anymore. That’s a huge change for artists all over the world. But so many African artists never made money from recordings. European and American artists used to make most of their money through sales, and when that was taken away, and they had to make big adjustments. African artists seem to adapt to this new reality better, because they never depended much on physical music sales. They rely on radio, endorsements, sponsorships, patrons, gigs, live shows. It’s patronage thing. The jackpot is to get a corporation behind you, to become a sponsor for a campaign by a beverage company, a cigarette or cellphone company, or whatever it might be. So these days, Rab is kind of a broker between artists and corporations, trying to find the right artist for their different campaigns. It's just a completely different model than anything we knew before.

And you have these musicians advertising in their recordings. “And this is going out to so-and-so and his store…” Which is fun. It's very interesting. But I don't know.

This is a big thing in Congolese music. That shouting out of patrons’ names, libanga. Morgan Greenstreet did an excellent Afropop Closeups podcast on this.

In a way, it's like what griots do.

Except that griots are supposed to know something about the people they praise. Sometimes these guys are just shouting out names.

And when that guy hears his name, he is in heaven.

And he shells out the bucks.

And he buys 100 records to give to his friends.

And he gives the artists money. That is how a lot of Congolese musicians make money now. I'm sure it happens in other countries, but it's a real informal system there.

What Rab is doing is quite interesting. But in order to sell something, you have to sell… something. What is it? We are selling what? We’re selling African music? Well, why not try? You know, I have a lot of bona fide DJs who come here from France and they go through my records. "Oh my God. You have this!” And they will tape it, because they can't find it anywhere else. This next-door neighbor of mine is a young guy who works at the World Bank, and they have big DJ concerts. He goes, and he plays a lot of African music. But first, he does stuff with it, remixing, changing the beat and all this. Since he travels a lot, he buys records wherever he goes.

But it’s getting hard to find records anymore. Even CDs. Everything is electronic.

It's horrible. We have to change that. But I think the role of Rab will be very important if he can really connect people, and it will be a boost African music, that's for sure. If it works.

I find it interesting that his goal, with all these techniques he’s using, is the same as what your goal was when you started putting that African and Latin segment in your show. You were trying to make listeners understand Africa in a different way, to connect on the cultural level. And we’re still fighting that same fight today. It's a long road.

It's a long road. And I don't know what the problem is. Because after all, almost all the music that you hear has an African root. But it’s like we’re fighting some dark shadow. It's ridiculous. Maybe it's our fault. We are doing Afropop, but we should do more. Television. Produce good stuff for television.

You know, the other day I was with a bunch of ministers, because I do some work at the World Bank as a communications specialist. And one of the guys from Uganda said, "You know what? You are always showing these pictures, beautiful pictures of Africa, and it's beautiful pictures of Africa begging. Why do we have to show constantly this poor woman carrying a huge basket on her head, going to her field. We don't need to show that all the time. We have great things in Africa. We have to show them too. Even to us." It's a question of pride. We have to change that.

You were talking about race records earlier, and how the DJs at VOA didn't want to touch them. I meet people all the time in interviews I do and conversations, who have a disparaging notion about of “pop music.” The word itself is somehow distasteful to a lot of people. Even Rab, who's dealing with Afrobeats and all this commercial stuff. He said he is not impressed with pop music. What impresses him is innovation and originality, and to him “pop music” means surrendering to formulas.

But then, I did another recent interview with Ian Brennan, who recorded prisoners in Malawi for the Zomba Prison Project. His passion is marginalized music, so you might've thought he would also shun pop culture. But at the end of the interview, he emphasized how important popular culture is, and how we’ve been “brainwashed” into thinking it’s trivial.” Any thoughts on that?

Well, you know, when I came back from America to France in the '70s, my first mission was I wanted to improve African music. Because Africa is so gifted musically. Everybody is a musician, basically. But everybody doesn't understand that music is something that you have to work on. You don’t just go in the studio and record. So I would go and bring some records to these big studios in Paris, when I had these African musicians. I’d say, “Listen to the guitar. Listen to the drums.” So they would listen and try to re-create that. And I would tell them, “Don't sell your soul to Babylon.” Because you know, to them, playing the kora, playing the balafon, was ridiculous. They would say, "You want us to play our traditional instruments, but when we can’t get a gig playing these instruments?” And I’d tell them, “It will come. It will come. Don't worry. Make something that will be strong. You can copy rock 'n' roll, you can copy all these things, but always keep your soul."

And that's why you had Youssou N’Dour becoming very popular, because it is Senegalese, but at the same time, that there's a lot of modern stuff behind it. Angelique Kidjo, same thing. All these people have this pop sound. That's very important, damn it. You want to do traditional stuff? You can. But pop music is very important. It’s music that people can understand. That's what African musicians can bring to the world. I think.

That's great. When you say you were going back to France and talking to African musicians in trying to to get them to improve, you're talking about the '60s? The '70s?

‘70s and ‘80s. I was in the studio a lot then. Hey, wait a minute; I made about 12 records myself. They were lousy, but.… [Laughs] I was working with Francis Bebey. We wrote a musical, the first African musical. And then we went bankrupt, because we didn't realize how much money it would take just to record the music. We were constantly in the studio. I always remember one morning where violinists of the Paris national orchestra came in. They were dressed in their little jackets. Blazers, with ascots. Grey pants. Very chic. Very elegant. And then suddenly had these African guys. You know, the drummers come in, half naked, with a necklace of panther teeth.

Oooo yeah!

And these orchestra guys were looking at them. "What the heck is going on?"

Well, speaking about the money, to some extent, the money comes from the audience. If the audience is willing to pay for the recording or the gig, then it works. We recently covered the One Africa Music Festival show at the Barclays Center, and it was all these big Afrobeats artists from Nigeria, but also Ghana, Sierra Leone... And there were 10,000 people there. I mean, when was the last time you saw an African concert with 10,000 people?

Wow.

And of those people had paid Barclays Center prices. They weren't coming to a free show at Central Park SummerStage. And who were they? They were young African diaspora, and Caribbean diaspora people. There was no more than a smattering of African-Americans, and hardly any white people at all.

Really?

And here are 10,000 of them listening to artists like Wizkid and Flavour and Tiwa Savage, and they are knowing the songs. Even if it's not their language. And they are dancing and moving and just going crazy. It's like they're seeing the Beatles. And I just looked at that and said, "O.K., whatever I might feel about this music, and however much I might think that the music of the '70s was richer and better, this is really happening.”

Crowd at One Africa Music Fest in Brooklyn

Crowd at One Africa Music Fest in Brooklyn

So let's end with this. Looking at the future, do you feel like with all the work you've done, and we've done, and people like Rab are doing, that it might actually work? Can we actually build a large, durable audience for African music in America?

Oh, yes. But we need more people than us. We need clout. We don't have clout. A lot of people don't realize how much work is going into these programs we’re doing. But if we had the clout to really get it out there, really produce something and promote it at another level. It's promotion, stupid.

But what would that look like?

I don’t know, we need to find people to give us the right kind of exposure. We need that big exposure.

Sounds like Donald Trump. "I’m gonna get the best people."

[Laughs] No, but this is not a joke. This is serious.

This is serious. But what was nice about the Icons and Innovators event last night was that you did feel like the generations could talk to each other. You spoke with those young artists and they were really interested in you what you had to say. And then when we got down to the music, you had these young dancers from Howard University, dancing to Samba Mapangala doing classic rumba songs. They were really into it.

Yeah, yeah.

And you just thought, it's not impossible that these generations can talk to each other.

We need more of that.

And we need to do more interviews, Georges. I’ll be back!