Blog March 24, 2014

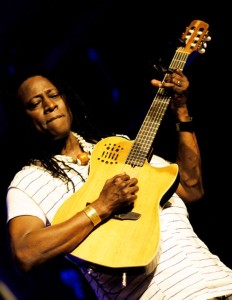

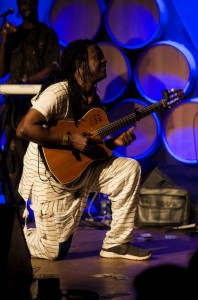

Habib Koite Celebrates His Homeland--Mali

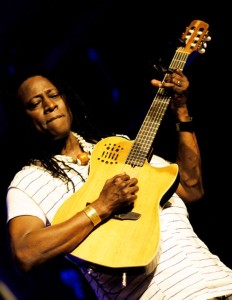

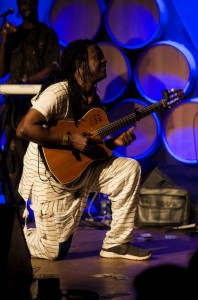

Habib Koite brought his new band to the City Winery in New York on March 6 for what turned out to be the best concert we've seen all year. The band is smaller and younger, and features Issa Kone on killer guitar and punchy banjo. Habib was looking fit, playing and singing at the top of his game, charming the crowd with his evolving English patter, and downright slaying them with his music. About the music, it was nearly all from his new, self-produced CD, Soo (Contre Jour). In a show that ran well over two hours, and included many visits to the stage by dancers and dashers, he played only two songs from the repertoire of his first four studio albums. Before the show, I caugh t up with Habib in the dressing room for a chat.

Banning Eyre: So, Habib, we missed your shows with Eric Bibb last year. How did that tour go?

Habib Koite: It was good. It was happy on stage. The gigs were great.

How did you meet Eric?

On tour. It was the promotional tour for the CD Mali to Memphis, the Putumayo compilation. They chose blues musicians, and bluesy music from Mali, from West Africa, and they made a promotional tour. This was 12 years ago. We met like that, and then afterwards, we met on the road in Australia, everywhere. And each time we talked, we talked about doing something together, and we did that two years ago. We met for five days in Brussels. We rehearsed in a hotel room, to see if we could do it. And the music was good.

The record is very sweet.

Eric came to Mali to make it. We tried to record in my son's home studio, but we had too many problems there. The electricity was coming and going, so we moved to a hotel. We rented one room in the hotel, and set up a studio. We recorded everything ourselves, with Daniel Boivin. He brought his computer. Then when the record came, we did a big tour—a lot of gigs in Europe, and in the U.S. A lot.

Just the two of you?

No, we took my young calabash player. So we were three on stage.

Still, a very small group. So that was a different experience for you, right?

Yes! A different experience, I tell you. Only three. For two songs, I played solo on stage, and Eric played two songs solo on stage. The other songs we played as three. Some of the songs mixed very well. The CD was good, but the gig was more interesting. On stage, we added new parts.

t up with Habib in the dressing room for a chat.

Banning Eyre: So, Habib, we missed your shows with Eric Bibb last year. How did that tour go?

Habib Koite: It was good. It was happy on stage. The gigs were great.

How did you meet Eric?

On tour. It was the promotional tour for the CD Mali to Memphis, the Putumayo compilation. They chose blues musicians, and bluesy music from Mali, from West Africa, and they made a promotional tour. This was 12 years ago. We met like that, and then afterwards, we met on the road in Australia, everywhere. And each time we talked, we talked about doing something together, and we did that two years ago. We met for five days in Brussels. We rehearsed in a hotel room, to see if we could do it. And the music was good.

The record is very sweet.

Eric came to Mali to make it. We tried to record in my son's home studio, but we had too many problems there. The electricity was coming and going, so we moved to a hotel. We rented one room in the hotel, and set up a studio. We recorded everything ourselves, with Daniel Boivin. He brought his computer. Then when the record came, we did a big tour—a lot of gigs in Europe, and in the U.S. A lot.

Just the two of you?

No, we took my young calabash player. So we were three on stage.

Still, a very small group. So that was a different experience for you, right?

Yes! A different experience, I tell you. Only three. For two songs, I played solo on stage, and Eric played two songs solo on stage. The other songs we played as three. Some of the songs mixed very well. The CD was good, but the gig was more interesting. On stage, we added new parts.

So then, you went back to Mali. I haven't seen you since the traumatic year of 2012 in Mali. What was your experience of all that political upheaval?

It was like a disaster in my soul. And in my mind. I couldn't believe what was happening to my country. What's happened? What's happened? But during the whole crisis, I traveled a lot. I played with a project called Five Great Guitars. That was in the Netherlands. They were jazz musicians, 55, 60 years old, and they wrote to me several times. Then, after I made the album with Eric, I went on tour with him too. I did go home. I went back to Mali, but I wasn't there the whole time. That's why sometimes I say I zapped some parts of this crisis. At one time, people could not play any music in the North, and at the same time, in the South, in the capital, they made a coup d'état, a political crisis, a big problem with the military. All at the same time.

I was in Bamako when they declared a state of emergency. They decided there should be no music, no big gatherings. The police were everywhere. The whole country could not make music. Everything was broken. A lot of the NGOs, and people who came from outside to work in Mali, everybody's offices were closed. They left. Big hotels were closed, completely closed. Dark, no light. When I saw this I was very sad. And sometimes, when I was going on tour in Europe, I would calm down a little, but when I came back home... But, OK, that was two years. Now, two years later, it's better.

Even for musicians?

For musicians, it's better now. It's not like before all this happened, but it's better. We can make concerts. It's not great. But it's better. For example, they can do the festival in Segu this year, but not the one in the desert. We hope to do that next year, to come and find a normal situation.

Afropop hopes we’re going to be able to come back to Mali next year. We’re working on a way to do that. Last summer, we saw musicians from the Festival in the Desert, Tartit, Mamadou Kelly, Imarhan. They were here, and we spoke a lot about what was going on. Their stories were pretty chilling. But during that period, you continue to write new songs.

So then, you went back to Mali. I haven't seen you since the traumatic year of 2012 in Mali. What was your experience of all that political upheaval?

It was like a disaster in my soul. And in my mind. I couldn't believe what was happening to my country. What's happened? What's happened? But during the whole crisis, I traveled a lot. I played with a project called Five Great Guitars. That was in the Netherlands. They were jazz musicians, 55, 60 years old, and they wrote to me several times. Then, after I made the album with Eric, I went on tour with him too. I did go home. I went back to Mali, but I wasn't there the whole time. That's why sometimes I say I zapped some parts of this crisis. At one time, people could not play any music in the North, and at the same time, in the South, in the capital, they made a coup d'état, a political crisis, a big problem with the military. All at the same time.

I was in Bamako when they declared a state of emergency. They decided there should be no music, no big gatherings. The police were everywhere. The whole country could not make music. Everything was broken. A lot of the NGOs, and people who came from outside to work in Mali, everybody's offices were closed. They left. Big hotels were closed, completely closed. Dark, no light. When I saw this I was very sad. And sometimes, when I was going on tour in Europe, I would calm down a little, but when I came back home... But, OK, that was two years. Now, two years later, it's better.

Even for musicians?

For musicians, it's better now. It's not like before all this happened, but it's better. We can make concerts. It's not great. But it's better. For example, they can do the festival in Segu this year, but not the one in the desert. We hope to do that next year, to come and find a normal situation.

Afropop hopes we’re going to be able to come back to Mali next year. We’re working on a way to do that. Last summer, we saw musicians from the Festival in the Desert, Tartit, Mamadou Kelly, Imarhan. They were here, and we spoke a lot about what was going on. Their stories were pretty chilling. But during that period, you continue to write new songs.

Yes. I did.

And I know from the past, that it's not easy for you to write new songs—not your favorite thing. So what was the story this time? What did you write about amid all this?

Well, in the beginning, everybody was asking me about a new album. This is how it started. Because the last album was seven years ago. I knew it was time to make another one. I was late. The producer, the fans, everybody is asking me, "Hey, where is it?" So I started. I had an idea, but I had not sat down and thought it through clearly. So I decided to take up the guitar, and start writing things down, figuring out parts. I would go to my farm and stay there the whole day. If I do this, it means it's serious now.

We decided to make an album that would be less expensive. The album I did with Eric Bibb was not that expensive to produce. We just recorded two people in one week. We practice and recorded, bang bang bang. We didn't spend much money on this project. But people like the album, we made a nice tour, and we sold a lot after the gigs. The producers made all their money back. Everybody was happy. There were a lot of people involved in this album with Eric and me, my company, his company, and everybody was happy. This was a good deal.

So after that, we had the idea to make an album more like that. Because my last album, Afriki, I recorded songs everywhere, some in Bamako, some in Belgium, some in Vermont in a studio with Jacob Edgar. The money for this album was too much. So this time everybody said, "Okay, you have to make something cheaper." We’re not going to bring a sound engineer from Europe. I have to find someone in Bamako. And the musicians would all come from Bamako. Everything done in Bamako, and afterwards we can do the mix in Europe. I said OK.

I was the producer. I organized everything. We recorded everything in my home. I called the sound engineer, Charly Coulibaly. My son recorded two songs himself, but most of them were done by Charly, and we did everything at home. Toumani [Diabate] came to my home to record one afternoon. Bassekou [Kouyate] came to play on the song "Terere." We would spend the whole day, nine in the morning to eight p.m. This was my first time to do this. I was the one to give the money, for the taxis, for the musicians’ sessions. At the end of each day, I would take my iPad and write everything down. I did everything myself. This is the first time.

Yes. I did.

And I know from the past, that it's not easy for you to write new songs—not your favorite thing. So what was the story this time? What did you write about amid all this?

Well, in the beginning, everybody was asking me about a new album. This is how it started. Because the last album was seven years ago. I knew it was time to make another one. I was late. The producer, the fans, everybody is asking me, "Hey, where is it?" So I started. I had an idea, but I had not sat down and thought it through clearly. So I decided to take up the guitar, and start writing things down, figuring out parts. I would go to my farm and stay there the whole day. If I do this, it means it's serious now.

We decided to make an album that would be less expensive. The album I did with Eric Bibb was not that expensive to produce. We just recorded two people in one week. We practice and recorded, bang bang bang. We didn't spend much money on this project. But people like the album, we made a nice tour, and we sold a lot after the gigs. The producers made all their money back. Everybody was happy. There were a lot of people involved in this album with Eric and me, my company, his company, and everybody was happy. This was a good deal.

So after that, we had the idea to make an album more like that. Because my last album, Afriki, I recorded songs everywhere, some in Bamako, some in Belgium, some in Vermont in a studio with Jacob Edgar. The money for this album was too much. So this time everybody said, "Okay, you have to make something cheaper." We’re not going to bring a sound engineer from Europe. I have to find someone in Bamako. And the musicians would all come from Bamako. Everything done in Bamako, and afterwards we can do the mix in Europe. I said OK.

I was the producer. I organized everything. We recorded everything in my home. I called the sound engineer, Charly Coulibaly. My son recorded two songs himself, but most of them were done by Charly, and we did everything at home. Toumani [Diabate] came to my home to record one afternoon. Bassekou [Kouyate] came to play on the song "Terere." We would spend the whole day, nine in the morning to eight p.m. This was my first time to do this. I was the one to give the money, for the taxis, for the musicians’ sessions. At the end of each day, I would take my iPad and write everything down. I did everything myself. This is the first time.

Let me ask you about some of the songs. The title song, "Soo," seems kind of like the spiritual center of the album, the idea of home.

Yeah. The song "Soo" comes from some deep thinking I did about Mali. I was very sad about the situation. As I was saying, I traveled a lot outside of my country during the crisis, but I was thinking a lot about my country when I was out. It's a place I love. I love the life there. Because I can spend two months out of my country, but I'm not really anywhere. During those two months, I'm moving each day, from one city to another city. That means I'm not really anywhere. I just wait to be somewhere, when I come back to my country. So I was thinking about this.

The crisis made me think we have to do more to make this homeland as sweet as it used to be. Because in the time of the crisis, my home lost the sweetness. So I was thinking about all the energy and synergy I could find to bring back this sweetness to Mali. That's why I talk about home. Soo is like your house in Bambara, the idea of being at home, in French chez soi. My house, my country, my home. I wanted to make people think about this, and what it means. And to think about what they know. Because they know that everyone has a homeland. So if I'm telling them they have a home, I'm not telling them something new. I'm just repeating what they already know. But I hope, when they listen to this, they can think again about this idea of homeland, and how to make it sweet. That's why I made this song, and why I called the album Soo.

And in the lyrics, I talk about people who are not at home, people who are outside their homeland. I tell them that they can have money, they can have a lot of things, but these other places can never be their homeland. Never.

Let me ask you about some of the songs. The title song, "Soo," seems kind of like the spiritual center of the album, the idea of home.

Yeah. The song "Soo" comes from some deep thinking I did about Mali. I was very sad about the situation. As I was saying, I traveled a lot outside of my country during the crisis, but I was thinking a lot about my country when I was out. It's a place I love. I love the life there. Because I can spend two months out of my country, but I'm not really anywhere. During those two months, I'm moving each day, from one city to another city. That means I'm not really anywhere. I just wait to be somewhere, when I come back to my country. So I was thinking about this.

The crisis made me think we have to do more to make this homeland as sweet as it used to be. Because in the time of the crisis, my home lost the sweetness. So I was thinking about all the energy and synergy I could find to bring back this sweetness to Mali. That's why I talk about home. Soo is like your house in Bambara, the idea of being at home, in French chez soi. My house, my country, my home. I wanted to make people think about this, and what it means. And to think about what they know. Because they know that everyone has a homeland. So if I'm telling them they have a home, I'm not telling them something new. I'm just repeating what they already know. But I hope, when they listen to this, they can think again about this idea of homeland, and how to make it sweet. That's why I made this song, and why I called the album Soo.

And in the lyrics, I talk about people who are not at home, people who are outside their homeland. I tell them that they can have money, they can have a lot of things, but these other places can never be their homeland. Never.

It seems like there's also a message in that song about what it means to make a home, the idea of unity, being together, and valuing each other. I think that's always been part of your work, you know, the way you have always performed different ethnic styles, including ones that aren't your own. I think that kind of spirit really got challenged during these recent events. You don't talk about this directly in the song, but I feel like you're commenting on it in a roundabout way, right?

Yes, you know, I don't want to be brutal. I know some lyrics are very tough. No, I don't like to be tough with my words. I want to say something soft, and people can think about the meaning, the other side of what I say. My words are based on the feelings I have in my soul. I try to call on the souls of people, to touch the soul. To make them think about their homeland.

The fact that you sing in so many different languages on the album is interesting. There's a message in that too, isn't there?

This idea of singing in different languages is for me a way to call people around me, and bring them around me, and give them the opportunity to be close, to be around someone. They can be close to me, and they can feel each other too, through my songs. I sing in the language of the Dogon people; many people don't sing in the Dogon language in Mali. But I tried to do it in a solo song, very clear. I want people to hear very well my voice and the words I say, even if they don't understand. Because all Malians don't understand Dogon language, but they recognize it. And that's the effect I wanted. They recognize the words, and they know it's me. It's not a Dogon guy; it's Habib. And the Dogon people can recognize their own language, sung by a Malian who comes from another part of Mali. That's the effect I wanted to create.

It's a beautiful song. Tell me what it says.

It's about a flag. It's called "Drapeau." It says to people, "You are welcome. Come

It seems like there's also a message in that song about what it means to make a home, the idea of unity, being together, and valuing each other. I think that's always been part of your work, you know, the way you have always performed different ethnic styles, including ones that aren't your own. I think that kind of spirit really got challenged during these recent events. You don't talk about this directly in the song, but I feel like you're commenting on it in a roundabout way, right?

Yes, you know, I don't want to be brutal. I know some lyrics are very tough. No, I don't like to be tough with my words. I want to say something soft, and people can think about the meaning, the other side of what I say. My words are based on the feelings I have in my soul. I try to call on the souls of people, to touch the soul. To make them think about their homeland.

The fact that you sing in so many different languages on the album is interesting. There's a message in that too, isn't there?

This idea of singing in different languages is for me a way to call people around me, and bring them around me, and give them the opportunity to be close, to be around someone. They can be close to me, and they can feel each other too, through my songs. I sing in the language of the Dogon people; many people don't sing in the Dogon language in Mali. But I tried to do it in a solo song, very clear. I want people to hear very well my voice and the words I say, even if they don't understand. Because all Malians don't understand Dogon language, but they recognize it. And that's the effect I wanted. They recognize the words, and they know it's me. It's not a Dogon guy; it's Habib. And the Dogon people can recognize their own language, sung by a Malian who comes from another part of Mali. That's the effect I wanted to create.

It's a beautiful song. Tell me what it says.

It's about a flag. It's called "Drapeau." It says to people, "You are welcome. Come  close to me. I have fresh water. Come close to me, we can stay together. I can give to you water, and we can help each other together to take our flag up." Up, up. During the crisis, the community of the Dogon made a group to go and talk with their Tamashek cousins up north. How do you say sanankou?

Well, I don't think we have an English word for that. But I know what it is. It's like joking cousins, people who have the right to be honest, kid, and even insult one another. It goes back to old history, right?

Yes, and the Dogon are the joking cousins of the Kel Tamashek [the Tuareg].

Oh, I see. That's interesting. I knew that families had that relationship, but I didn't really see it extended the whole ethnic groups.

The Dogon people and the Kel Tamashek are sanankou. That's why a big association of Dogon people went up to the north. I think they went to Kidal, and they talked, just one year ago. It went very well, because they knew they were going to join their joking cousins, and they were free to talk to them. And the Kel Tamashek must welcome them too.

And they did.

Yes, yes. And for this reason, I said, okay, I’m going to sing about a flag, I want to sing in the Dogon language.

Again, you're doing it in a roundabout way, but you're saying that Mali has to stay one country, not be divided as many Tamashek would like.

Yeah. Yeah. Everybody has to come together and take this flag up.

close to me. I have fresh water. Come close to me, we can stay together. I can give to you water, and we can help each other together to take our flag up." Up, up. During the crisis, the community of the Dogon made a group to go and talk with their Tamashek cousins up north. How do you say sanankou?

Well, I don't think we have an English word for that. But I know what it is. It's like joking cousins, people who have the right to be honest, kid, and even insult one another. It goes back to old history, right?

Yes, and the Dogon are the joking cousins of the Kel Tamashek [the Tuareg].

Oh, I see. That's interesting. I knew that families had that relationship, but I didn't really see it extended the whole ethnic groups.

The Dogon people and the Kel Tamashek are sanankou. That's why a big association of Dogon people went up to the north. I think they went to Kidal, and they talked, just one year ago. It went very well, because they knew they were going to join their joking cousins, and they were free to talk to them. And the Kel Tamashek must welcome them too.

And they did.

Yes, yes. And for this reason, I said, okay, I’m going to sing about a flag, I want to sing in the Dogon language.

Again, you're doing it in a roundabout way, but you're saying that Mali has to stay one country, not be divided as many Tamashek would like.

Yeah. Yeah. Everybody has to come together and take this flag up.

That's beautiful. Tell me about the first song on the album "Dėmė."

Most of the songs on this album are about the homeland, Malian society, about neighbors, and the relationship between neighbors. It's about neighborhood—young people who play football in the afternoon when they don't have to be in school. This is not the football of the big stadium. This is just 8, 10, 16-year-old kids. The neighbors come and watch them in the afternoon, the family—mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers. Everyone comes around, and there’s noise, the sound of the neighborhood. We live outside on the street, and we make a lot of noise, but it's a good noise, because it's the noise of life, the noise of your neighbors. Normal life. There's an ambience I want to talk about because it's alive. It's a reality, and it's very interesting for the relationships between neighbors.

So dėmė is help, helping. It's about the people who help each other. If you are helping, you are a good human being. It means that you observe others. You know when someone is suffering or someone needs something they don't have, and you can give that to them, or help them. It means you don't just look at the sky, or look at the earth and walk. It means you are a good person, and you take care of other people. I ask everybody to be helping. If you are helping, you can have a good life because you give others the opportunity to have a good life too. It's about this kind of interaction.

You do have one song here that's about not being at home. And that's "L.A."

[LAUGHS.] "L.A.," yes. I love Los Angeles. Los Angeles is sunny, not too much cold. I love this city and the houses, the short houses. I know there are some higher buildings to, but most of the houses are short. The weather...

And what else?

That's beautiful. Tell me about the first song on the album "Dėmė."

Most of the songs on this album are about the homeland, Malian society, about neighbors, and the relationship between neighbors. It's about neighborhood—young people who play football in the afternoon when they don't have to be in school. This is not the football of the big stadium. This is just 8, 10, 16-year-old kids. The neighbors come and watch them in the afternoon, the family—mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers. Everyone comes around, and there’s noise, the sound of the neighborhood. We live outside on the street, and we make a lot of noise, but it's a good noise, because it's the noise of life, the noise of your neighbors. Normal life. There's an ambience I want to talk about because it's alive. It's a reality, and it's very interesting for the relationships between neighbors.

So dėmė is help, helping. It's about the people who help each other. If you are helping, you are a good human being. It means that you observe others. You know when someone is suffering or someone needs something they don't have, and you can give that to them, or help them. It means you don't just look at the sky, or look at the earth and walk. It means you are a good person, and you take care of other people. I ask everybody to be helping. If you are helping, you can have a good life because you give others the opportunity to have a good life too. It's about this kind of interaction.

You do have one song here that's about not being at home. And that's "L.A."

[LAUGHS.] "L.A.," yes. I love Los Angeles. Los Angeles is sunny, not too much cold. I love this city and the houses, the short houses. I know there are some higher buildings to, but most of the houses are short. The weather...

And what else?

[LAUGHS.] I remember when I was traveling with Eric Bibb there and we arrived late at night. We were going to find something to eat, and this was the last restaurant. They were ready to close. And we asked the guy; I spoke to him in English. I said, "We are a band, we just want something to eat. Please..." And he said, "Well, where you from?" And I said, "I'm from Belgium." And he looked at me, and he answered me, "You’re from Belgium? I'm from Belgium too." And now he changed, and he spoke to me in French. I was surprised, because my story wasn't true, but his was. He really was from Belgium. So then he said, "Okay, my kitchen is closed, but I can make chicken wings for you." And then he brought us something to drink, and he brought some wings, and french fries. We had a good moment together.

And was the thing he brought to drink tequila? Like in the song?

Well, yes, we did taste a little, just a little.

Uh huh. "One shot, two shot, three shot, for shot, five..."

Well, this was for the song. In reality, no. Five is a lot!

[LAUGHS.] I remember when I was traveling with Eric Bibb there and we arrived late at night. We were going to find something to eat, and this was the last restaurant. They were ready to close. And we asked the guy; I spoke to him in English. I said, "We are a band, we just want something to eat. Please..." And he said, "Well, where you from?" And I said, "I'm from Belgium." And he looked at me, and he answered me, "You’re from Belgium? I'm from Belgium too." And now he changed, and he spoke to me in French. I was surprised, because my story wasn't true, but his was. He really was from Belgium. So then he said, "Okay, my kitchen is closed, but I can make chicken wings for you." And then he brought us something to drink, and he brought some wings, and french fries. We had a good moment together.

And was the thing he brought to drink tequila? Like in the song?

Well, yes, we did taste a little, just a little.

Uh huh. "One shot, two shot, three shot, for shot, five..."

Well, this was for the song. In reality, no. Five is a lot! I have to ask you about one more thing. The banjo. That's a new sound in your band.

Hey, the banjo was a gift from Eric Bibb. When we finished the last tour, I had been playing one song solo with the banjo. I played "Khafole," the same song that I play here on the new CD. I was doing a solo version on banjo, and at the end of the tour, he gave it to me. And I brought it to Mali, and when I started to make my album, I thought about what to do with it. I gave the banjo to Issa Kone, and he plays it on three or four songs. It's good. The sound of the banjo and the djembe give something new, something clear and open.

It's a nice element, and we know, of course, that the banjo came from Africa in the first place.

Yes. So I hear.

And are you using it in the show now?

Yes! Ah, if you don't have a banjo, we don't play. No, no, no.

That's great. I'm going to let you prepare for the show now. But it's wonderful to catch up.

Say hello to everyone at Afropop. I hope to see Sean Barlow.

You will, on the stage dashing you, no doubt!

[caption id="attachment_17459" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

I have to ask you about one more thing. The banjo. That's a new sound in your band.

Hey, the banjo was a gift from Eric Bibb. When we finished the last tour, I had been playing one song solo with the banjo. I played "Khafole," the same song that I play here on the new CD. I was doing a solo version on banjo, and at the end of the tour, he gave it to me. And I brought it to Mali, and when I started to make my album, I thought about what to do with it. I gave the banjo to Issa Kone, and he plays it on three or four songs. It's good. The sound of the banjo and the djembe give something new, something clear and open.

It's a nice element, and we know, of course, that the banjo came from Africa in the first place.

Yes. So I hear.

And are you using it in the show now?

Yes! Ah, if you don't have a banjo, we don't play. No, no, no.

That's great. I'm going to let you prepare for the show now. But it's wonderful to catch up.

Say hello to everyone at Afropop. I hope to see Sean Barlow.

You will, on the stage dashing you, no doubt!

[caption id="attachment_17459" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Sean Barlow dashes Habib, and dances takamba to the song "Fatima."[/caption]

Sean Barlow dashes Habib, and dances takamba to the song "Fatima."[/caption]

t up with Habib in the dressing room for a chat.

Banning Eyre: So, Habib, we missed your shows with Eric Bibb last year. How did that tour go?

Habib Koite: It was good. It was happy on stage. The gigs were great.

How did you meet Eric?

On tour. It was the promotional tour for the CD Mali to Memphis, the Putumayo compilation. They chose blues musicians, and bluesy music from Mali, from West Africa, and they made a promotional tour. This was 12 years ago. We met like that, and then afterwards, we met on the road in Australia, everywhere. And each time we talked, we talked about doing something together, and we did that two years ago. We met for five days in Brussels. We rehearsed in a hotel room, to see if we could do it. And the music was good.

The record is very sweet.

Eric came to Mali to make it. We tried to record in my son's home studio, but we had too many problems there. The electricity was coming and going, so we moved to a hotel. We rented one room in the hotel, and set up a studio. We recorded everything ourselves, with Daniel Boivin. He brought his computer. Then when the record came, we did a big tour—a lot of gigs in Europe, and in the U.S. A lot.

Just the two of you?

No, we took my young calabash player. So we were three on stage.

Still, a very small group. So that was a different experience for you, right?

Yes! A different experience, I tell you. Only three. For two songs, I played solo on stage, and Eric played two songs solo on stage. The other songs we played as three. Some of the songs mixed very well. The CD was good, but the gig was more interesting. On stage, we added new parts.

t up with Habib in the dressing room for a chat.

Banning Eyre: So, Habib, we missed your shows with Eric Bibb last year. How did that tour go?

Habib Koite: It was good. It was happy on stage. The gigs were great.

How did you meet Eric?

On tour. It was the promotional tour for the CD Mali to Memphis, the Putumayo compilation. They chose blues musicians, and bluesy music from Mali, from West Africa, and they made a promotional tour. This was 12 years ago. We met like that, and then afterwards, we met on the road in Australia, everywhere. And each time we talked, we talked about doing something together, and we did that two years ago. We met for five days in Brussels. We rehearsed in a hotel room, to see if we could do it. And the music was good.

The record is very sweet.

Eric came to Mali to make it. We tried to record in my son's home studio, but we had too many problems there. The electricity was coming and going, so we moved to a hotel. We rented one room in the hotel, and set up a studio. We recorded everything ourselves, with Daniel Boivin. He brought his computer. Then when the record came, we did a big tour—a lot of gigs in Europe, and in the U.S. A lot.

Just the two of you?

No, we took my young calabash player. So we were three on stage.

Still, a very small group. So that was a different experience for you, right?

Yes! A different experience, I tell you. Only three. For two songs, I played solo on stage, and Eric played two songs solo on stage. The other songs we played as three. Some of the songs mixed very well. The CD was good, but the gig was more interesting. On stage, we added new parts.

So then, you went back to Mali. I haven't seen you since the traumatic year of 2012 in Mali. What was your experience of all that political upheaval?

It was like a disaster in my soul. And in my mind. I couldn't believe what was happening to my country. What's happened? What's happened? But during the whole crisis, I traveled a lot. I played with a project called Five Great Guitars. That was in the Netherlands. They were jazz musicians, 55, 60 years old, and they wrote to me several times. Then, after I made the album with Eric, I went on tour with him too. I did go home. I went back to Mali, but I wasn't there the whole time. That's why sometimes I say I zapped some parts of this crisis. At one time, people could not play any music in the North, and at the same time, in the South, in the capital, they made a coup d'état, a political crisis, a big problem with the military. All at the same time.

I was in Bamako when they declared a state of emergency. They decided there should be no music, no big gatherings. The police were everywhere. The whole country could not make music. Everything was broken. A lot of the NGOs, and people who came from outside to work in Mali, everybody's offices were closed. They left. Big hotels were closed, completely closed. Dark, no light. When I saw this I was very sad. And sometimes, when I was going on tour in Europe, I would calm down a little, but when I came back home... But, OK, that was two years. Now, two years later, it's better.

Even for musicians?

For musicians, it's better now. It's not like before all this happened, but it's better. We can make concerts. It's not great. But it's better. For example, they can do the festival in Segu this year, but not the one in the desert. We hope to do that next year, to come and find a normal situation.

Afropop hopes we’re going to be able to come back to Mali next year. We’re working on a way to do that. Last summer, we saw musicians from the Festival in the Desert, Tartit, Mamadou Kelly, Imarhan. They were here, and we spoke a lot about what was going on. Their stories were pretty chilling. But during that period, you continue to write new songs.

So then, you went back to Mali. I haven't seen you since the traumatic year of 2012 in Mali. What was your experience of all that political upheaval?

It was like a disaster in my soul. And in my mind. I couldn't believe what was happening to my country. What's happened? What's happened? But during the whole crisis, I traveled a lot. I played with a project called Five Great Guitars. That was in the Netherlands. They were jazz musicians, 55, 60 years old, and they wrote to me several times. Then, after I made the album with Eric, I went on tour with him too. I did go home. I went back to Mali, but I wasn't there the whole time. That's why sometimes I say I zapped some parts of this crisis. At one time, people could not play any music in the North, and at the same time, in the South, in the capital, they made a coup d'état, a political crisis, a big problem with the military. All at the same time.

I was in Bamako when they declared a state of emergency. They decided there should be no music, no big gatherings. The police were everywhere. The whole country could not make music. Everything was broken. A lot of the NGOs, and people who came from outside to work in Mali, everybody's offices were closed. They left. Big hotels were closed, completely closed. Dark, no light. When I saw this I was very sad. And sometimes, when I was going on tour in Europe, I would calm down a little, but when I came back home... But, OK, that was two years. Now, two years later, it's better.

Even for musicians?

For musicians, it's better now. It's not like before all this happened, but it's better. We can make concerts. It's not great. But it's better. For example, they can do the festival in Segu this year, but not the one in the desert. We hope to do that next year, to come and find a normal situation.

Afropop hopes we’re going to be able to come back to Mali next year. We’re working on a way to do that. Last summer, we saw musicians from the Festival in the Desert, Tartit, Mamadou Kelly, Imarhan. They were here, and we spoke a lot about what was going on. Their stories were pretty chilling. But during that period, you continue to write new songs.

Yes. I did.

And I know from the past, that it's not easy for you to write new songs—not your favorite thing. So what was the story this time? What did you write about amid all this?

Well, in the beginning, everybody was asking me about a new album. This is how it started. Because the last album was seven years ago. I knew it was time to make another one. I was late. The producer, the fans, everybody is asking me, "Hey, where is it?" So I started. I had an idea, but I had not sat down and thought it through clearly. So I decided to take up the guitar, and start writing things down, figuring out parts. I would go to my farm and stay there the whole day. If I do this, it means it's serious now.

We decided to make an album that would be less expensive. The album I did with Eric Bibb was not that expensive to produce. We just recorded two people in one week. We practice and recorded, bang bang bang. We didn't spend much money on this project. But people like the album, we made a nice tour, and we sold a lot after the gigs. The producers made all their money back. Everybody was happy. There were a lot of people involved in this album with Eric and me, my company, his company, and everybody was happy. This was a good deal.

So after that, we had the idea to make an album more like that. Because my last album, Afriki, I recorded songs everywhere, some in Bamako, some in Belgium, some in Vermont in a studio with Jacob Edgar. The money for this album was too much. So this time everybody said, "Okay, you have to make something cheaper." We’re not going to bring a sound engineer from Europe. I have to find someone in Bamako. And the musicians would all come from Bamako. Everything done in Bamako, and afterwards we can do the mix in Europe. I said OK.

I was the producer. I organized everything. We recorded everything in my home. I called the sound engineer, Charly Coulibaly. My son recorded two songs himself, but most of them were done by Charly, and we did everything at home. Toumani [Diabate] came to my home to record one afternoon. Bassekou [Kouyate] came to play on the song "Terere." We would spend the whole day, nine in the morning to eight p.m. This was my first time to do this. I was the one to give the money, for the taxis, for the musicians’ sessions. At the end of each day, I would take my iPad and write everything down. I did everything myself. This is the first time.

Yes. I did.

And I know from the past, that it's not easy for you to write new songs—not your favorite thing. So what was the story this time? What did you write about amid all this?

Well, in the beginning, everybody was asking me about a new album. This is how it started. Because the last album was seven years ago. I knew it was time to make another one. I was late. The producer, the fans, everybody is asking me, "Hey, where is it?" So I started. I had an idea, but I had not sat down and thought it through clearly. So I decided to take up the guitar, and start writing things down, figuring out parts. I would go to my farm and stay there the whole day. If I do this, it means it's serious now.

We decided to make an album that would be less expensive. The album I did with Eric Bibb was not that expensive to produce. We just recorded two people in one week. We practice and recorded, bang bang bang. We didn't spend much money on this project. But people like the album, we made a nice tour, and we sold a lot after the gigs. The producers made all their money back. Everybody was happy. There were a lot of people involved in this album with Eric and me, my company, his company, and everybody was happy. This was a good deal.

So after that, we had the idea to make an album more like that. Because my last album, Afriki, I recorded songs everywhere, some in Bamako, some in Belgium, some in Vermont in a studio with Jacob Edgar. The money for this album was too much. So this time everybody said, "Okay, you have to make something cheaper." We’re not going to bring a sound engineer from Europe. I have to find someone in Bamako. And the musicians would all come from Bamako. Everything done in Bamako, and afterwards we can do the mix in Europe. I said OK.

I was the producer. I organized everything. We recorded everything in my home. I called the sound engineer, Charly Coulibaly. My son recorded two songs himself, but most of them were done by Charly, and we did everything at home. Toumani [Diabate] came to my home to record one afternoon. Bassekou [Kouyate] came to play on the song "Terere." We would spend the whole day, nine in the morning to eight p.m. This was my first time to do this. I was the one to give the money, for the taxis, for the musicians’ sessions. At the end of each day, I would take my iPad and write everything down. I did everything myself. This is the first time.

Let me ask you about some of the songs. The title song, "Soo," seems kind of like the spiritual center of the album, the idea of home.

Yeah. The song "Soo" comes from some deep thinking I did about Mali. I was very sad about the situation. As I was saying, I traveled a lot outside of my country during the crisis, but I was thinking a lot about my country when I was out. It's a place I love. I love the life there. Because I can spend two months out of my country, but I'm not really anywhere. During those two months, I'm moving each day, from one city to another city. That means I'm not really anywhere. I just wait to be somewhere, when I come back to my country. So I was thinking about this.

The crisis made me think we have to do more to make this homeland as sweet as it used to be. Because in the time of the crisis, my home lost the sweetness. So I was thinking about all the energy and synergy I could find to bring back this sweetness to Mali. That's why I talk about home. Soo is like your house in Bambara, the idea of being at home, in French chez soi. My house, my country, my home. I wanted to make people think about this, and what it means. And to think about what they know. Because they know that everyone has a homeland. So if I'm telling them they have a home, I'm not telling them something new. I'm just repeating what they already know. But I hope, when they listen to this, they can think again about this idea of homeland, and how to make it sweet. That's why I made this song, and why I called the album Soo.

And in the lyrics, I talk about people who are not at home, people who are outside their homeland. I tell them that they can have money, they can have a lot of things, but these other places can never be their homeland. Never.

Let me ask you about some of the songs. The title song, "Soo," seems kind of like the spiritual center of the album, the idea of home.

Yeah. The song "Soo" comes from some deep thinking I did about Mali. I was very sad about the situation. As I was saying, I traveled a lot outside of my country during the crisis, but I was thinking a lot about my country when I was out. It's a place I love. I love the life there. Because I can spend two months out of my country, but I'm not really anywhere. During those two months, I'm moving each day, from one city to another city. That means I'm not really anywhere. I just wait to be somewhere, when I come back to my country. So I was thinking about this.

The crisis made me think we have to do more to make this homeland as sweet as it used to be. Because in the time of the crisis, my home lost the sweetness. So I was thinking about all the energy and synergy I could find to bring back this sweetness to Mali. That's why I talk about home. Soo is like your house in Bambara, the idea of being at home, in French chez soi. My house, my country, my home. I wanted to make people think about this, and what it means. And to think about what they know. Because they know that everyone has a homeland. So if I'm telling them they have a home, I'm not telling them something new. I'm just repeating what they already know. But I hope, when they listen to this, they can think again about this idea of homeland, and how to make it sweet. That's why I made this song, and why I called the album Soo.

And in the lyrics, I talk about people who are not at home, people who are outside their homeland. I tell them that they can have money, they can have a lot of things, but these other places can never be their homeland. Never.

It seems like there's also a message in that song about what it means to make a home, the idea of unity, being together, and valuing each other. I think that's always been part of your work, you know, the way you have always performed different ethnic styles, including ones that aren't your own. I think that kind of spirit really got challenged during these recent events. You don't talk about this directly in the song, but I feel like you're commenting on it in a roundabout way, right?

Yes, you know, I don't want to be brutal. I know some lyrics are very tough. No, I don't like to be tough with my words. I want to say something soft, and people can think about the meaning, the other side of what I say. My words are based on the feelings I have in my soul. I try to call on the souls of people, to touch the soul. To make them think about their homeland.

The fact that you sing in so many different languages on the album is interesting. There's a message in that too, isn't there?

This idea of singing in different languages is for me a way to call people around me, and bring them around me, and give them the opportunity to be close, to be around someone. They can be close to me, and they can feel each other too, through my songs. I sing in the language of the Dogon people; many people don't sing in the Dogon language in Mali. But I tried to do it in a solo song, very clear. I want people to hear very well my voice and the words I say, even if they don't understand. Because all Malians don't understand Dogon language, but they recognize it. And that's the effect I wanted. They recognize the words, and they know it's me. It's not a Dogon guy; it's Habib. And the Dogon people can recognize their own language, sung by a Malian who comes from another part of Mali. That's the effect I wanted to create.

It's a beautiful song. Tell me what it says.

It's about a flag. It's called "Drapeau." It says to people, "You are welcome. Come

It seems like there's also a message in that song about what it means to make a home, the idea of unity, being together, and valuing each other. I think that's always been part of your work, you know, the way you have always performed different ethnic styles, including ones that aren't your own. I think that kind of spirit really got challenged during these recent events. You don't talk about this directly in the song, but I feel like you're commenting on it in a roundabout way, right?

Yes, you know, I don't want to be brutal. I know some lyrics are very tough. No, I don't like to be tough with my words. I want to say something soft, and people can think about the meaning, the other side of what I say. My words are based on the feelings I have in my soul. I try to call on the souls of people, to touch the soul. To make them think about their homeland.

The fact that you sing in so many different languages on the album is interesting. There's a message in that too, isn't there?

This idea of singing in different languages is for me a way to call people around me, and bring them around me, and give them the opportunity to be close, to be around someone. They can be close to me, and they can feel each other too, through my songs. I sing in the language of the Dogon people; many people don't sing in the Dogon language in Mali. But I tried to do it in a solo song, very clear. I want people to hear very well my voice and the words I say, even if they don't understand. Because all Malians don't understand Dogon language, but they recognize it. And that's the effect I wanted. They recognize the words, and they know it's me. It's not a Dogon guy; it's Habib. And the Dogon people can recognize their own language, sung by a Malian who comes from another part of Mali. That's the effect I wanted to create.

It's a beautiful song. Tell me what it says.

It's about a flag. It's called "Drapeau." It says to people, "You are welcome. Come  close to me. I have fresh water. Come close to me, we can stay together. I can give to you water, and we can help each other together to take our flag up." Up, up. During the crisis, the community of the Dogon made a group to go and talk with their Tamashek cousins up north. How do you say sanankou?

Well, I don't think we have an English word for that. But I know what it is. It's like joking cousins, people who have the right to be honest, kid, and even insult one another. It goes back to old history, right?

Yes, and the Dogon are the joking cousins of the Kel Tamashek [the Tuareg].

Oh, I see. That's interesting. I knew that families had that relationship, but I didn't really see it extended the whole ethnic groups.

The Dogon people and the Kel Tamashek are sanankou. That's why a big association of Dogon people went up to the north. I think they went to Kidal, and they talked, just one year ago. It went very well, because they knew they were going to join their joking cousins, and they were free to talk to them. And the Kel Tamashek must welcome them too.

And they did.

Yes, yes. And for this reason, I said, okay, I’m going to sing about a flag, I want to sing in the Dogon language.

Again, you're doing it in a roundabout way, but you're saying that Mali has to stay one country, not be divided as many Tamashek would like.

Yeah. Yeah. Everybody has to come together and take this flag up.

close to me. I have fresh water. Come close to me, we can stay together. I can give to you water, and we can help each other together to take our flag up." Up, up. During the crisis, the community of the Dogon made a group to go and talk with their Tamashek cousins up north. How do you say sanankou?

Well, I don't think we have an English word for that. But I know what it is. It's like joking cousins, people who have the right to be honest, kid, and even insult one another. It goes back to old history, right?

Yes, and the Dogon are the joking cousins of the Kel Tamashek [the Tuareg].

Oh, I see. That's interesting. I knew that families had that relationship, but I didn't really see it extended the whole ethnic groups.

The Dogon people and the Kel Tamashek are sanankou. That's why a big association of Dogon people went up to the north. I think they went to Kidal, and they talked, just one year ago. It went very well, because they knew they were going to join their joking cousins, and they were free to talk to them. And the Kel Tamashek must welcome them too.

And they did.

Yes, yes. And for this reason, I said, okay, I’m going to sing about a flag, I want to sing in the Dogon language.

Again, you're doing it in a roundabout way, but you're saying that Mali has to stay one country, not be divided as many Tamashek would like.

Yeah. Yeah. Everybody has to come together and take this flag up.

That's beautiful. Tell me about the first song on the album "Dėmė."

Most of the songs on this album are about the homeland, Malian society, about neighbors, and the relationship between neighbors. It's about neighborhood—young people who play football in the afternoon when they don't have to be in school. This is not the football of the big stadium. This is just 8, 10, 16-year-old kids. The neighbors come and watch them in the afternoon, the family—mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers. Everyone comes around, and there’s noise, the sound of the neighborhood. We live outside on the street, and we make a lot of noise, but it's a good noise, because it's the noise of life, the noise of your neighbors. Normal life. There's an ambience I want to talk about because it's alive. It's a reality, and it's very interesting for the relationships between neighbors.

So dėmė is help, helping. It's about the people who help each other. If you are helping, you are a good human being. It means that you observe others. You know when someone is suffering or someone needs something they don't have, and you can give that to them, or help them. It means you don't just look at the sky, or look at the earth and walk. It means you are a good person, and you take care of other people. I ask everybody to be helping. If you are helping, you can have a good life because you give others the opportunity to have a good life too. It's about this kind of interaction.

You do have one song here that's about not being at home. And that's "L.A."

[LAUGHS.] "L.A.," yes. I love Los Angeles. Los Angeles is sunny, not too much cold. I love this city and the houses, the short houses. I know there are some higher buildings to, but most of the houses are short. The weather...

And what else?

That's beautiful. Tell me about the first song on the album "Dėmė."

Most of the songs on this album are about the homeland, Malian society, about neighbors, and the relationship between neighbors. It's about neighborhood—young people who play football in the afternoon when they don't have to be in school. This is not the football of the big stadium. This is just 8, 10, 16-year-old kids. The neighbors come and watch them in the afternoon, the family—mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers. Everyone comes around, and there’s noise, the sound of the neighborhood. We live outside on the street, and we make a lot of noise, but it's a good noise, because it's the noise of life, the noise of your neighbors. Normal life. There's an ambience I want to talk about because it's alive. It's a reality, and it's very interesting for the relationships between neighbors.

So dėmė is help, helping. It's about the people who help each other. If you are helping, you are a good human being. It means that you observe others. You know when someone is suffering or someone needs something they don't have, and you can give that to them, or help them. It means you don't just look at the sky, or look at the earth and walk. It means you are a good person, and you take care of other people. I ask everybody to be helping. If you are helping, you can have a good life because you give others the opportunity to have a good life too. It's about this kind of interaction.

You do have one song here that's about not being at home. And that's "L.A."

[LAUGHS.] "L.A.," yes. I love Los Angeles. Los Angeles is sunny, not too much cold. I love this city and the houses, the short houses. I know there are some higher buildings to, but most of the houses are short. The weather...

And what else?

[LAUGHS.] I remember when I was traveling with Eric Bibb there and we arrived late at night. We were going to find something to eat, and this was the last restaurant. They were ready to close. And we asked the guy; I spoke to him in English. I said, "We are a band, we just want something to eat. Please..." And he said, "Well, where you from?" And I said, "I'm from Belgium." And he looked at me, and he answered me, "You’re from Belgium? I'm from Belgium too." And now he changed, and he spoke to me in French. I was surprised, because my story wasn't true, but his was. He really was from Belgium. So then he said, "Okay, my kitchen is closed, but I can make chicken wings for you." And then he brought us something to drink, and he brought some wings, and french fries. We had a good moment together.

And was the thing he brought to drink tequila? Like in the song?

Well, yes, we did taste a little, just a little.

Uh huh. "One shot, two shot, three shot, for shot, five..."

Well, this was for the song. In reality, no. Five is a lot!

[LAUGHS.] I remember when I was traveling with Eric Bibb there and we arrived late at night. We were going to find something to eat, and this was the last restaurant. They were ready to close. And we asked the guy; I spoke to him in English. I said, "We are a band, we just want something to eat. Please..." And he said, "Well, where you from?" And I said, "I'm from Belgium." And he looked at me, and he answered me, "You’re from Belgium? I'm from Belgium too." And now he changed, and he spoke to me in French. I was surprised, because my story wasn't true, but his was. He really was from Belgium. So then he said, "Okay, my kitchen is closed, but I can make chicken wings for you." And then he brought us something to drink, and he brought some wings, and french fries. We had a good moment together.

And was the thing he brought to drink tequila? Like in the song?

Well, yes, we did taste a little, just a little.

Uh huh. "One shot, two shot, three shot, for shot, five..."

Well, this was for the song. In reality, no. Five is a lot! I have to ask you about one more thing. The banjo. That's a new sound in your band.

Hey, the banjo was a gift from Eric Bibb. When we finished the last tour, I had been playing one song solo with the banjo. I played "Khafole," the same song that I play here on the new CD. I was doing a solo version on banjo, and at the end of the tour, he gave it to me. And I brought it to Mali, and when I started to make my album, I thought about what to do with it. I gave the banjo to Issa Kone, and he plays it on three or four songs. It's good. The sound of the banjo and the djembe give something new, something clear and open.

It's a nice element, and we know, of course, that the banjo came from Africa in the first place.

Yes. So I hear.

And are you using it in the show now?

Yes! Ah, if you don't have a banjo, we don't play. No, no, no.

That's great. I'm going to let you prepare for the show now. But it's wonderful to catch up.

Say hello to everyone at Afropop. I hope to see Sean Barlow.

You will, on the stage dashing you, no doubt!

[caption id="attachment_17459" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

I have to ask you about one more thing. The banjo. That's a new sound in your band.

Hey, the banjo was a gift from Eric Bibb. When we finished the last tour, I had been playing one song solo with the banjo. I played "Khafole," the same song that I play here on the new CD. I was doing a solo version on banjo, and at the end of the tour, he gave it to me. And I brought it to Mali, and when I started to make my album, I thought about what to do with it. I gave the banjo to Issa Kone, and he plays it on three or four songs. It's good. The sound of the banjo and the djembe give something new, something clear and open.

It's a nice element, and we know, of course, that the banjo came from Africa in the first place.

Yes. So I hear.

And are you using it in the show now?

Yes! Ah, if you don't have a banjo, we don't play. No, no, no.

That's great. I'm going to let you prepare for the show now. But it's wonderful to catch up.

Say hello to everyone at Afropop. I hope to see Sean Barlow.

You will, on the stage dashing you, no doubt!

[caption id="attachment_17459" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Sean Barlow dashes Habib, and dances takamba to the song "Fatima."[/caption]

Sean Barlow dashes Habib, and dances takamba to the song "Fatima."[/caption]