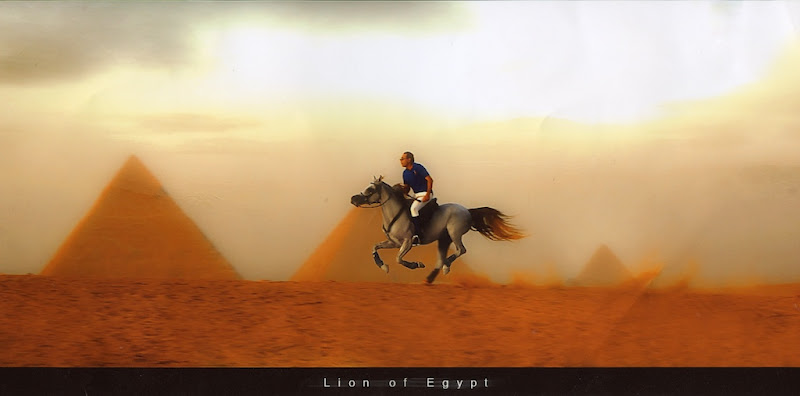

Hakim is known as “The Lion of Egypt.” From the moment he sprang onto the scene in 1991, he became one of the most beloved singers of the popular sha’bi style ever. The voice is undeniably powerful—searing and joyous. Afropop’s Sean Barlow and Banning Eyre have known Hakim since his American visits in the early 2000s, and particularly recall his double bill with Khaled (of Algeria) at New York’s Town Hall in February, 2002, a triumphant assertion of peace and harmony in the wake of the 911 attacks. In the summer of 2011, Hakim received the two Afropop producers in Cairo with warmth and hospitality. Sean and Banning accompanied Hakim to two weddings where he sang with his band in a single night, and afterwards accompanied him on a sunrise ride by the pyramids. It turns out, Hakim is a horse enthusiast, and owns a beautiful Arabian of his own. (See Banning’s blog post on that adventure.) A few nights later, they were treated to a spectacular meal at Hakim’s home. Afterwards, they sat down with Hakim and his wife Jihane. Hakim alternates between his own basic, but improving, English, and Arabic, translated by Jihane. Here’s their conversation.

B.E.: Hakim, I want to start with your beginnings. I just learned that you come from the south, Upper Egypt. Talk a little bit about where you were born, and your childhood.

Hakim: It was in Upper Egypt. I had a normal childhood, like any Egyptian kid living in the South, in Upper Egypt. What made me like music, actually… I started because I was listening a lot to Sufi music. That's what made me really like music. And then I started doing the same way as to Sufi, me being the main singer, and having the kids around me doing the dance. I used to imitate all those Sheikhs, like the ones you are seeing tomorrow, [Afropop was on its way to a moulid, a Sufi saint celebration, in Assyut]. I used to imitate the way each of them sang. Each one with his own style.

B.E.: Nice. Was this happening in a city or a small town?

Hakim: Zawyet el Gedami. It's a village, north of Assyut. The first village after Minya.

B.E.: So you are a natural. You are hearing music, and just singing it on your own. When you came to Cairo, how old are you, and how did you become more formally educated in music? How did you learn music in Cairo?

Hakim: I came to Cairo already knowing music. Naturally. With my friends. In my small village. When I go to school, I make with my friends a small band. When I grow up, and they go to school, I listen to more music, and make a small band with my friends. We made parties for birthdays of my friends. On a school trip, when we go to Minya, or we go to play soccer, we would make small songs for the team of the school. And the Maghagha club also. We were training about instrument, a small instrument, the oud, a small organ, keyboard. With time, I set about making a bigger band. Every year, I add something new. I start with tabla and daff, and mazhar [double reed oboe]. Like you saw in the zar yesterday.

B.E.: And this is still in Upper Egypt, not Cairo.

Hakim: Not Cairo. Upper Egypt. And I make work with people older than me. This is my idea. Because I need to learn. From where I learn music? I find ways to learn. I have to work with people older than me. Musicians. I start to talk with them, and I go with them, and I bring someone from a small band. I take ideas, and I take something for my band, until step-by-step, or gradually, my band bigger, bigger, bigger. In Minya. When I was 20 years, I had the biggest band in Minya.

B.E.: And how did your family, and parents take this?

Hakim: Oh! War. War with my family. War.

B.E.: They just didn't like it.

Hakim: I didn't talk with my father, I didn't talk with my mother. And my brother also. I am very bad. All the time I am bad. I don't know what I do. I like this way. Never did I see another work. Never. Never. When I was in school, every time I saw me as the singer, and all the audience with me in the class, my audience, my fans. LAUGHS. All the time. This dream never goes out of my mind.

B.E.: So your mother and father didn't speak with you, but they couldn't stop you.

Hakim: Never. There was something in my blood. In my blood. Here. I feel it, but I can't explain. I can't explain my feeling this way. It's something I feel but I can't explain to my father, to my mother. I think my friends, I can't explain what I do know. But I like this way.

B.E.: Later on, when you became successful, did your parents change your mind and come to accept?

Hakim: Yes, my father wanted to take pictures with me.

Jihane: His father wanted to take pictures with him once he became known.

B.E.: When was that?

Hakim: First album. 1991. And the people know Hakim, and magazines write about me, and newspapers write about me, and TV talks about me. My father and my family thought that this was something interesting. Something good. They think about me, this is for play. Just that I'm playing. Not reality. They don't believe in my talent. Until that first album. After first album, everybody say, "Yes, okay. No problem. This is reality."

B.E.: So, how old were you when you came to Cairo?

Hakim: When I came for the new album?

B.E.: Well, before that. Did you move to Cairo first?

Hakim: I came to Cairo a lot of times when I was in university. Azhar University.

B.E.: Ah, so you came to go to school.

Hakim: Yes, for study. And I also came for the work, and I said to myself I wouldn’t go back to the village again, after to become “Hakim.” Until I was 28. I don't go back to Minya.

Jihane: He said, “I will only go back if I become famous.”

B.E.: I see. I read that during that time you used to spend the time with musicians on Mohamed Ali Street, a place where there were a lot of musicians.

Hakim: Yes. Between 17 and 19 years old. Because I need to have experience with music. I have the basics.

B.E.: You have the voice.

Hakim: Yes, because I worked in Minya a lot, with my band, with other bands, other musicians. I take experience, and I talk with any musician, the musicians language. I learned the music language so I would be able to communicate with other musicians.

B.E.: Maqam [Arab musical modes] and things like that.

Hakim: Maqam and rhythms. Yes. Right.

B.E.: I read a story about the first song you recorded, or the beginning of your recording career. It involved Hamid el Shari. It involved your niece recording a commercial. Do you remember the story?

Hakim: LAUGHS When my family don't agree about my talent, my niece make commercial for children's milk, and go to make film for commercial for children's milk. And her father meets with Hamid el Shari, and talks with him about me, for send me to Hamid el Shari. He said to have made, "Hakim, he will come to meet with you. And please, please, tell him, ‘You don't have talent. You go to your village. Stay there. Better.’” This is deal with Hamid el Shari for me to stop. Hamid say, "Okay, okay." A lot of people come here, and my brother called me in my village. "Come, come, Hamid wants to listen to you. Go. Go." This time, I hate Hamid el Shari and his music. Never did I believe in his music. And I said to my brother, "What? Hamid el Shari? Why? I want a company, a record company to make a contract with them." "No, no, no. Come to Hamid. Hamid is good. You will make something. Come anyway. Come."

"Okay, okay." I came with my appointment. "Hi, I'm here. Hi, hello. How are you?" Here my experience made something with Hamid. Because I spoke to him with music language. I spoke with him about maqam, bayathi, rast, saba. And Hamid, "Ah, wow. Oh. Ooo." This was Friday. 5 PM. He said to me, "Hakim, look, today I can't meet with you more. But come Monday in another studio, M-Sound, at eight o'clock. You know the studio?" "Yes, I know the studio." "Okay, bye-bye."

I go to the studio, another studio, and wait for Hamid. Hamid comes, and a lot of people come also. "Ah, Hakim, how are you today? We need to listen to you." "Okay, no problem." "Go inside the studio." The first time I go to a studio and I sing with a microphone for the studio. This day.

B.E.: Do you remember what you sang?

Hakim: Yes. Something for Adaweyya. And Fatma Eid, Abdel Ghanni El Sayyed.

Jihane: You sang all of this?

Hakim: Yes. Abdu El Soroogi. Something old and something new at this time. And the people behind the glass, everybody frowns. No expression. Except one. One person. The sound engineer. Until now I remember his smile. Until now. The only one who was smiling. If you his name is Ahmed Azah. I didn't see him again. He was the only one that was smiling of all the people. And I remember his smile. After I finished, someone comes with me. "I am Fayez Aziz with Sonar company. We need to sign with you." I was dreaming with Sonar company.

Jihane: His dream was to sign with this company.

Hakim: This was my dream. Sonar. Biggest company. Biggest company in Middle East. Mohamed Mounir was there. Many artists.

B.E.: So maybe they had thought you would not be good because your relatives had told them to discourage you. Do you think that's why they weren't smiling? But they were happy when they heard you.

Hakim: I think. I think.

B.E.: So when is this happening?

Jihane: Summer, 1990.

B.E.: So those singers whose songs you sang were sha'bi singers. Sha'bi was pretty established then. But did you know that that was the right kind of music for you?

Hakim: Yes, sha'bi music. But I needed to make something new with sha'bi music

B.E.: You knew that right from the beginning.

Hakim: Yes. And this is the project for Sonar also. At the same time. But they didn't find a singer.

B.E.: They were looking for somebody.

Hakim: Yes, they were looking for a singer to do this project. And Hamid also. Hamid el Shari also wanted to make something new for sha'bi music.

Jihane: So Basma, his niece, is the reason why Hamid el Shari and Hakim and Sonar all met and all did what they wanted to do. LAUGHS

B.E.: That's beautiful. And that’s how you started working with Hamid el Shari, and you are still friends.

Hakim: Until now.

B.E.: Do you like his music now?

Hakim: Yes! LAUGHS. Don't tell him. Now I love him. I love him. My love.

B.E.: So, you made the first album. You wanted to make something new with sha'bi music. What was new in the very beginning, in that first record?

Hakim: The music was very new, for sha'bi music. Instruments. All the instruments. Hamid El Shari's fingers, on the keyboard, this is new. The first time there is keyboard for sha'bi music. The first time electric bass for sha'bi music.

B.E.: So Adaweyya, it's violin, percussion, but no keyboard, no bass, no drums. You added those things. Who is writing the songs?

Hakim: Amal El Tair for lyrics and Hassan Ishish composer. And Hamid el Shari, arranger, producer. The album, Nazra [A Glance].

B.E.: And what happened after it was released?

Hakim: I don't know. The rain has come. In three days. Number one in the Middle East. Like a bird flu! Really. Really. Like bird flu. LAUGHS

B.E.: Were you surprised?

Hakim: Yes. Sure. Shocked. I could not believe it. I was crazy. What is that?

B.E.: And then, more records, more success, concerts.

Hakim: Yes. Al Hamdo-lillah [thanks to God].

B.E.: Now I understand that sha'bi music was not really supported by the media. People thought of it is vulgar and low or whatever. But they were putting you on television. What had changed? What was different?

Hakim: The person who said this about sha'bi music, and no one is able to say it even now, was Abdel Halim Hafez talking about Adaweyya. Because sha'bi music before Abdel Halim Hafez was number one. When Abdel Halim Hafez came into the scene, he turned to the music and took it to a more romantic feeling, romantic rhythms and romantic melodies. At the same time a singer called Mohamed Roshdi, very sha'bi, came up and he crushed him in popularity. Crushed them so much that Abdel Halim Hafez started to sing sha'bi, and he took all the arrangers, the composers, the authors, from this Mohammed Roshdi and made them work with him.

B.E.: This was in the 1970s?

Hakim: The 60s. That's the right history. But nobody can say that. Nobody has been able to really say that.

B.E.: People talk about the 70s, but this is earlier.

Hakim: Then at this time Abdel Halim became also at the top. And he is fighting Umm Kulthum and Farid al-Atrache on another side, and from another side, he is also at war with Mohamed Roshdi. But he cannot say he is trying to compete or making war with Mohamed Roshdi, this sha'bi singer. And at the same time, he's taking Abdel Wahab under his arm, because they were together in their record company. Who came on the scene? Adaweyya. And Adaweyya, in the card game, he took all the cards and put them in his pocket. Everybody turned their attention to Adaweyya. Abdel Halim, Abdel Wahab, Umm Kulthum. All of them. Farid al Atrache. Those people at this time were like the pyramids. Everybody switch to what's happening with this guy. Adaweyya. Who's that? Somebody super small, like Adaweyya, changed the whole scene. So who started to fight that specific image of sha'bi that you are talking about was Abdel Halim.

B.E.: And he was powerful.

Jihane: That's what he is saying. Abdel Halim and Umm Kulthum, they were the pyramids.

Hakim: Abdel Nasser used to go and make peace between Abdel Halim and Umm Kulthum. Yes. Really. And when they had concerts where they were together, also there were a few times where there were insults on air. They even banned Abdel Halim from going on air for a while. So Abdel Halim fought Adaweyya and made a war, a Cold War, making people feel that listening to Adaweyya was not class, it was vulgar. But at the same time, he was singing sha'bi. Songs that until now are still hits are sha'bi. Mohamed Roshdi also sang one of these songs. So he was singing sha'bi but at the same time fighting this Adaweyya who is getting huge popularity, just saying that he was vulgar and so on. And until the end, he never would say that he sang sha'bi. But they know, the singers know. The sha'bi has a way, the way the lyrics are written, the sound, the way you sing, you know it's sha'bi.

B.E.: And you know this because of the language, the fact that it's the language of the street. Is that right?

Hakim: Yes. It talks to the people straight. With their language. But the romantic songs are more. "Have you seen the moon?..." For them, the sha'bi singers, "You think I'm blind? Of course I see the moon." So it's more straight. I love you, and I want you. Sha'bi.

B.E.: Now, is there still this attitude today? In the media, and on television? Because I've read about a television program that was supposed to focus on artists but whenever they would talk about, or talk to, sha'bi artists, they would be very condescending, according to this article more like an interrogation than an interview. So is this still a factor?

Hakim: No. The media now is open to it. In the last 10 years, there are a few singers who have come out who have done songs that they thought was sha'bi, but it's very raw. Like a monlolgue. Like standup comedy. Not sha'bi. They say it's sha'bi, but me, as a sha'bi singer, I say it's not. It's standup comedy. And this has led the media to talk about this new wave of singers.

Like a singer who says, "I smoked two stones on the shisha." Stones is when they changed the shisha bowl. That's not a sha'bi song. Who cares that he smoked this or that with his friends? And another singer said, "I smoked a brown cigarette." Meaning hashish. A brown cigarette is hashish. "And I feel that my head is crashing. And I'm sitting in the streets, passed out. And the laundry is dripping on me, but I don't know from what street. The street that was in the back of me has become in front of me." I spoke about the song in an interview. I said, "This guy is a genius." This is a message of say no to drugs. Because he's explaining. Two weeks after, he did another song. First it was I smoked a brown cigarette. Now it was, "I drank two beers."

B.E.: So this does not qualify as sha'bi for you?

Hakim: No, never.

B.E.: Sha'bi is mostly about love, right?

Hakim: Daily life. Love. Nostalgia. Missing home. Jealousy. The description of woman. How to get her, to tease her, to attract her. To seduce her the fastest way.

B.E.: Let's talk about some of your most important songs. I read about a song of years from 2004 that brought in some aspect of Upper Egypt, saidi culture. Do you know the song I'm talking about?

Hakim: In all my albums, there's always one song that has a saidi rhythm. Like “Amalna Elli Alena” [We Have Done What We Can (and the rest is up to God)] SINGS Even the way I sing in the pronunciation, I do it in a saidi way.

B.E.: Tell me about your big hits, and what it was that made them big?

Hakim: “Efred Masalan” (Suppose, for Example), “El Hob Nadani” (Love Called Out to Me), “Essalamo ‘Alaykum” (God Be With You). “Nar” (Fire, My Heart is On). “Nazra” (One Look or A Glance).

B.E.: That’s your first song, from the beginning.

Hakim: Yes. And the latest “Kalam be Kalam” (Words for Words).

B.E.: That's the one you've just done?

Hakim: No, that's another one. Not yet. “El Layla Leltak” (This Night is Your Night). "Efred" is a genius montage between the words and the melodies and the arrangements. Until today, we don't know the whole of it. This was the third CD. 1996. “El Hobb Nadani” is because of the melody. The melody is from the street, it comes from the vendors on the street. The beginning of it.

B.E.: Can you sing it?

Hakim: SINGS In the beginning. That's it. This from the street. This is why it became so famous. The theme is from the people. I remember a friend of mine was in a taxi cab. And this song came on the radio. So the taxi driver started to sing, so my friend asked him afterwards, "Why are you singing the song?" He said, "Because I feel that the melody is inside of me, and finally I found words to the melody." That's why he could relate to it.

B.E.: All the time you've been recording new songs, traveling around the world, playing big concerts, you still keep playing these weddings like we saw the other night. Tell me what that means to you. On the one hand, you're singing to a big audience around the world. But on the other hand, you're walking into a family setting, a family you don't necessarily know, a more intimate setting... Tell me what this means to you?

Hakim: The feeling is one. I love music. Even if it's at a wedding, a party, a concert. If it's on the street. In the bathroom. I feel music in my veins. I sing for Hakim. I sing to make myself happy, because I love singing. I sing to please myself, because I feel I have something nobody else has. And also, the most important times I have, the nicest times, the best times I have, are when I'm on stage. I was still the bed, "When I'm on stage, I'm somewhere else." Utopia. And I'm always scared that somebody might come and wake me up. That's why don't like until now that someone comes and touches me while I'm singing. When I used to sing back in my hometown, in Minya, in Upper Egypt, I used to get very annoyed or upset or scared when someone would touch me, as it would take me out of my trance. It would take me out of my mood.

B.E.: But at weddings, they touch you a lot.

Hakim: Yes. They touch me a lot, and I don't like it. People want to take pictures with me.

B.E.: So this is why the stage is something higher than the wedding. The wedding is a connection with people. But the stage is something more, art.

Hakim: Inside of myself, I present the same way at the wedding or on stage. But the wedding, yes, that will be more personal, because that person really likes me, and he's inviting me to sing at his wedding. And when I go in, I really try to be part of the family. With the bride and groom. And I feel it really from my heart, and I think it is projected to the people.

B.E.: Beautiful. Now, you played for a little bit of your new CD, Ya Mazago (His/Her Mood), the one you just recorded. Maybe by the time we have the show, we will have the CD. Tell us about the new CD.

Hakim: Before I go the to the new CD, I must tell you, that the wedding crowd are the ones who made the concert crowd. Because they are the ones who wait for me at the concerts. Because at the weddings, they've been able to see me, to touch me, to connect with me, so they love me. They are the ones. That's why at the concerts, we always wait, and take pictures with everybody. I will be the last person leaving the place. Last one!

B.E.: That's dedication.

Hakim: Yes. I love it. This is my job. And you saw how the bride was that day. LAUGHS. She didn't feel that I was a cousin or brother. She felt like I was the groom.

B.E.: That might explain why the groom was looking a little bit out of sorts.

Hakim: Okay, the CD. Don't think about the bride... Shh shh! So it’s 11 songs. I really suffered, not suffered, but I really worked a lot on this CD. This was particularly tiring. I think what tires me is that I take time. The singers here, you will see that every year they released an album. I release every 2 1/2 years, and this one took 3 1/2 years. Just now, I thought that maybe because I take so much time, to listen to the same songs, to go and repeat and readjust. That's why it's so tiring.

B.E.: It really sounded fantastic when we were losing in your car the other day. Tell us about a couple of the songs.

Hakim: I have a song called "Kollena Wahed" (We Are One). The song talks about unifying the Arab world, and also the unifying of the Egyptian people. Muslims with Christians. We have to be one. This is the most important song. This is for Muslim people here in Egypt, Christian people. We have to be one. This is my target. With my song, my new song. "Kollena Wahed." All one.

B.E.: That's a good message for now.

Hakim: Yes, a good message for now. And there's another song called "Akher Sazaga." (How Naïve!). It talks about kindness with a lover, a girlfriend. This is more of a drama song. It's about he is so kind with her that they treated him like he's stupid.

Jihane: Meaning that here, they will say that if you are kind, you are stupid.

Hakim: And there are other songs on Ya Mazago, songs that are really of the people. An example is “Elli Rabba” (S/he Who Has Raised) and the namesake of the album, “Ya Mazago” (His/her Mood). The people are going to like it. Those songs are all being downloaded now as cellphone ringtones. Because we release the ringtones in the summer. All the people at Egyptian television have my song on their ring tone. They were telling me about this. A lot of people have this ring tone.

Jihane: You know, at the Egyptian television, they have a lot of people. 60,000 people work there. It's very big. So a lot of them have that ring tone.

B.E.: That's great. Well, when you make people wait for 3 1/2 years, they are hungry.

Hakim: Yes, everybody asks.

B.E.: Well, I can't wait to get to know it. It sounded great while we were driving to your favorite breakfast spot, Malky, the other day.

Hakim: Yes!

B.E.: That was great, Hakim. I will never forget that. So, I want to end with a philosophical question. Obviously, we don't know where Egypt’s revolution is going to end. But I want ask you about the cultural side, especially music. Where do you think Egypt’s music is heading in the wake of this revolution?

Hakim: First, the political issue has to be solved before we can even start to talk about what could happen with the music. What I could hope is that with this revolution, with this eye on Egypt right now, because there is an eye on Egypt right now, that maybe the music could reach a wider audience, more ears around the world. So this is what I hope for the music, that it will have a chance to be heard all around. And on a small note, I know also that the singers will be the last people to start working again. Really.

B.E.: Well, I think you are right that this is the moment of opportunity. Do you think music played any role in the revolution? I know there was a lot of singing in Tahrir Square. Some singers have actually changed their reputations and careers, for better or worse. Do you think music had a role in this revolution?

Hakim: Yes, of course, there was a lot of singing in Tahrir. A lot of people were singing Revolution songs and songs of the moment. But I also think the songs are not what's going to make the difference. The songs encouraged them. They have the energy inside of them. They have the drive to do it. And probably, the singing was encouraging them. But there is the after also. The drive should be well put and well used. Like, for example, what I did a few months ago, I started a campaign to cancel the debt Egypt. Well, not cancel. But for the people who have loaned money to Egypt to stop for five years putting interest on it. So that Egypt can recuperate. It would be great if you could also help us with that.

You know, when Obama did his speech about the Arab world here, he took off $1 billion. He reduced the debt. I will tell you how he did it. He took it from one place, and put it in another. A place where it will work for Egypt. So he didn't cancel it, but 1 billion is basically one dinner for the 80 million people we have here. It needs to be reinforced. It's a step, but not enough. If you can help with this, it would be great. What we want is not to cancel the debt, but just to stop the interest for five years. So we can breathe. So the economy can start again little by little. This is what one can do, what I can do for the revolution. Not only singing... Yes, it's nice singing and all this, but is not necessary to charge people up all the time. They are already charged. Now, we need to think about other things. I know the music is important, but other things are also important.

You know, when Obama did his speech about the Arab world here, he took off $1 billion. He reduced the debt. I will tell you how he did it. He took it from one place, and put it in another. A place where it will work for Egypt. So he didn't cancel it, but 1 billion is basically one dinner for the 80 million people we have here. It needs to be reinforced. It's a step, but not enough. If you can help with this, it would be great. What we want is not to cancel the debt, but just to stop the interest for five years. So we can breathe. So the economy can start again little by little. This is what one can do, what I can do for the revolution. Not only singing... Yes, it's nice singing and all this, but is not necessary to charge people up all the time. They are already charged. Now, we need to think about other things. I know the music is important, but other things are also important.

B.E.: Good.

Hakim: I hope to help with this project. I want to concentrate on it.

Sean.: You should send Obama a copy of your new CD. He probably gets 1000 things today. But I bet he'd like it.

Hakim: Yeah, maybe we could gather the artists, the big artists that do a lot for charity, for economic justice, to help to support this campaign. And also the radio and the journalists. I have said this already in Egypt, but I want to start publicizing this in the world. We are not saying cancel the debt. We just want to stop the interest for five years. And then we will start. Because so much of this money was stolen. We don't know where it went. And it is us who is now left to pay.

B.E.: Thanks, Hakim. This has been great.