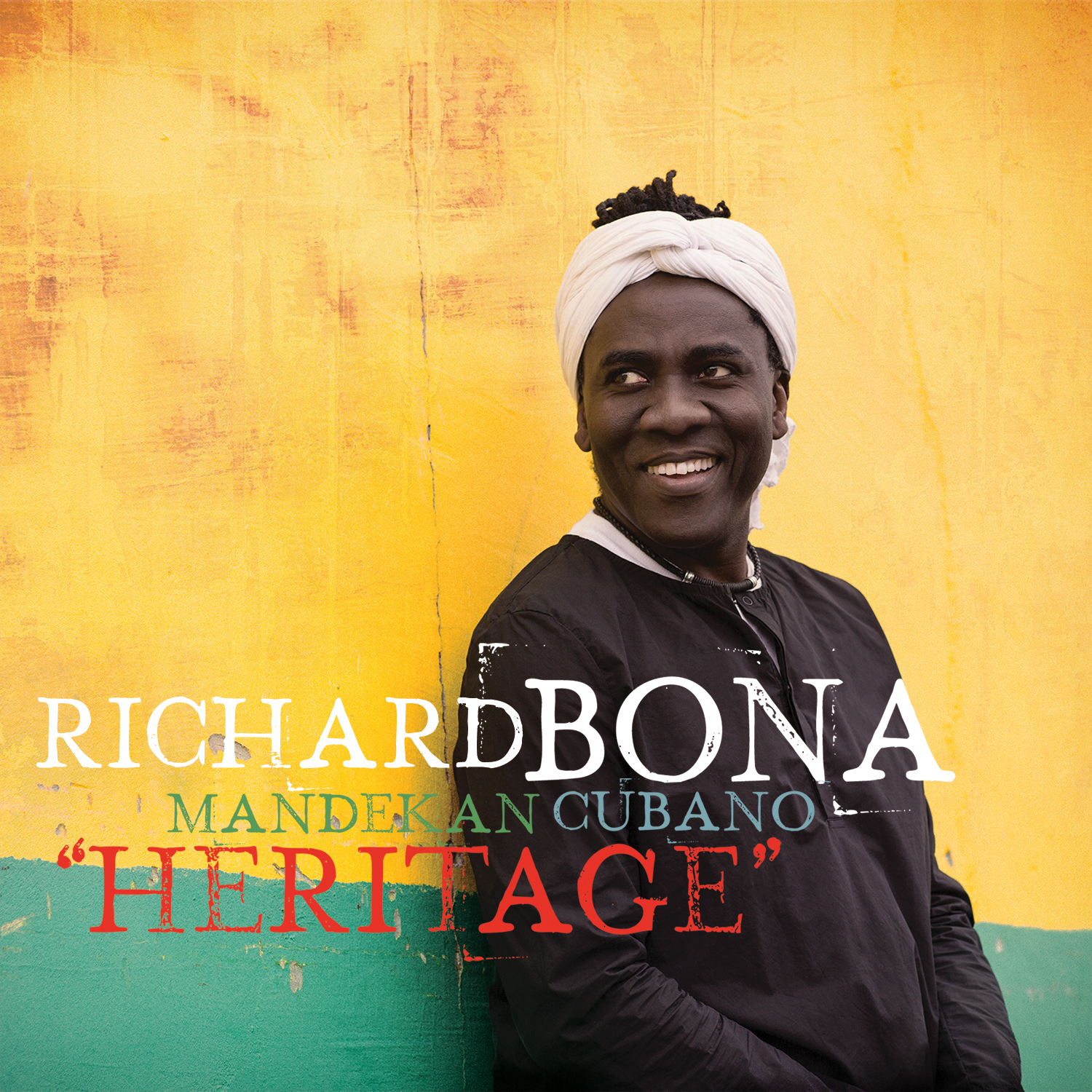

Richard Bona's music is as well-traveled as the man himself. For his latest record, Heritage, the New Yorker-by-way-of-Paris-and-Cameroon plays with a group called Mandekan Cubano. The album, released by Quincy Jones' Qwest Records, explores the verdant and vast world of Afro-Cuban music in Bona's characteristically clean, clear style.

If he was only just a bass player, Richard Bona would still be “someone to know.” His list of collaborators runs from George Benson to Stevie Wonder to Harry Belafonte to Bobby McFerrin. But his albums under his own name reveal him to be a gifted arranger, a dulcet vocalist, and deft musical chameleon. It's probably easier to describe Bona as a “world jazz fusion artist” but he's also someone who wrote a song called “African Cowboy,” complete with the sawing fiddles that the name implies.

His latest album focuses on Afro-Cuban music. Given that Cuban music underpins so much jazz and African music, it should be no surprise that the album feels so natural, so perfectly within Bona's wheelhouse. “The first day I visited Cuba, I felt like I was home” Bona told Jazziz magazine.

There's no untangling who's influencing whom when it comes to Cuba and West Africa, and so much the better. Enslaved peoples from West Africa preserved their musical traditions as much as possible. In the Caribbean those traditions fused with French and Spanish musical styles and instruments. The transformed music appeared (or reappeared) on the continent in first half of the 20th century via the famous G.V. record series. To call it “influential” is an understatement. Highlife in Ghana, Congolese rumba, Senegal's Orchestra Baobab—calling it “Afro-Cuban” just sounds redundant.

To Bona, it all makes perfect sense. “Anywhere in Africa people will start dancing to a Cuban band without even questioning who is playing,” he says. “What connects black music is a clave. Hand drums come from Africa so we hear our history talking. You feel it.”

The musical traditions that Bona plays with, like salsa, are fairly structured, but he and the group manage to find new wrinkles and give their own distinctive twists. The opening track, "Aka Lingala Tè," is a multitracked Bona a cappella piece, sung in the Congolese language Lingala, which translates to "I don't speak Lingala." The most obvious departure from the Cuban source material, of course, is that otherwise Bona mostly sings in the Cameroonian language Douala rather than Spanish, and his bass playing is also pretty unmistakably African.

You can hear those big African Bakithi Kumalo-style flourishes on “Essèwè Ya Monique.” Percussion, synthesizer and piano take center stage on “Jokoh Jokoh,” but they all glide along tracks laid by Bona's bass. Where some Cuban and Cuban-inspired music will build to a frenzy, on record at least, Bona and the band stay neatly in the pocket, the call and response rising and falling like waves against the shore. It would be interesting to experience the songs in person, which people in New York will have the opportunity to do on Dec. 16, 2016, at the Bona-owned Club Bonafide on 52nd Street.

As a proud descendant of a griot family, Bona thinks of himself as a storyteller, and someone who preserves a culture orally. On their latest record, Bona and Mandekan Cubano revel in their Heritage.