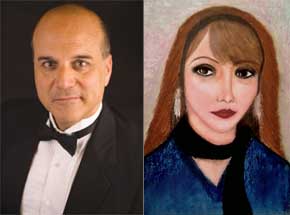

Kenneth Habib is an Associate Professor in Ethnomusicology, Music Theory, and Music History at the California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo. He wrote his PhD dissertation on Fairuz, the preeminent singer of Lebanon, and the Rahbani family of composer poets whose careers have been so closely tied with hers. Banning Eyre spoke with Ken for Afropop Worldwide’s Hip Deep program, “Lebanon 1: Fairuz, A Woman for All Seasons.” It turned out that Ken is so good at discussing this topic that Banning had scarcely to ask questions. So we present this as, essentially, a spoken essay. Note that many sources spell the singer’s name “Fairouz,” and in other ways as well. Here, we use Ken Habib’s preferred spelling.

Introduction

My name is Ken Habib. I first saw Fairuz perform live in her famous 1981 concert tour of the United States. It was at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, and I’d say that that really awoke in me something that I knew was there lifelong in terms of my interest in my heritage and, in particular, my Lebanese cultural background. All four of my grandparents are from Lebanon, and so I fit into the legacy of migrants from what was called Greater Syria at that time.

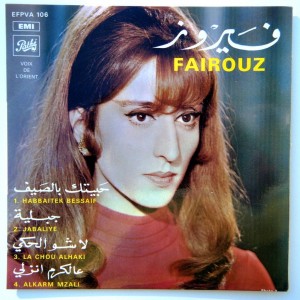

I couldn’t tell you the first time I heard a Fairuz song; it was doubtless as a child, going to any number of weddings and dancing a dabke as a kid. That was the favorite part of a wedding, definitely—the celebration afterward with food and dancing and what have you. So, that’s how I first became introduced to the music of Fairuz. Then, living abroad with a writing career in Saudi Arabia for a couple of years in my mid-twenties, I began buying Fairuz albums in earnest. But it was only after I returned to school to go into music on a full-time basis—I had been playing music since I was about ten—and studying classical voice and composition, getting my master’s degree in composition, and then going into ethnomusicology for my PhD—that I decided to focus on the Middle East and American popular music, which were my two main interests. And when I did that, I came in knowing that I really wanted to focus on Lebanon and, in particular, Fairuz.

I’ll provide some quick facts about Fairuz herself before we get into what we might call the larger Fairuz phenomenon. Her born name is Nuhad Haddad. She was born in 1935 in the vicinity of the Lebanese capital, Beirut, to a Syriac Catholic father and a Maronite Catholic mother. And I say that, in part, because of the religious complexity of Lebanon with its wide-ranging religious make-up and backgrounds that to some degree characterize the country. And so, Fairuz, along with the Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum, is the most famous and accomplished of modern Arab singers. Her singing is still regarded as of the highest standard, and among her well-known monikers is “Our Ambassador to the Stars.” Umm Kulthum had her celestial moniker too, “The Star of the East.”

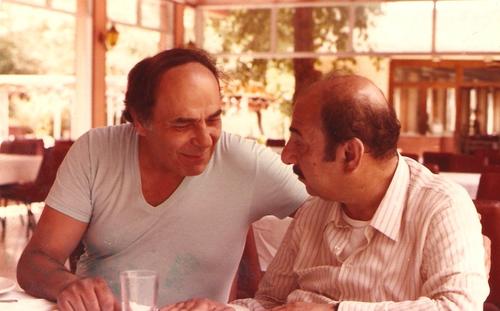

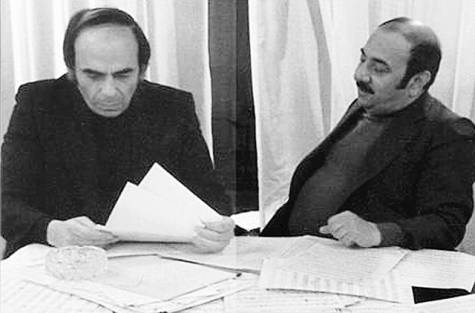

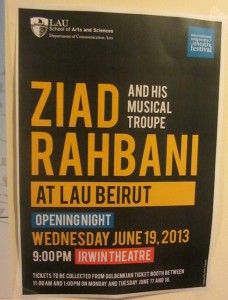

Fairuz’s work has been nearly exclusively with the Rahbani family of composer poets, and so let me also provide some quick facts on these composers. They’re a family, the Rahbani family, and they hail from Antilyas, which is north of Beirut, and have an Orthodox Christian background, and the first two of them, you might say the primary two, the ones who, together with Fairuz, really launched the whole phenomenon, are two brothers: Assi and Mansour. Assi Rahbani was born in 1923 and died in 1986, and Mansour was born in 1925 and died in 2009, and the two of them were brilliant composer poets and artists in very large senses of the words. And they went on with Fairuz, as a team, to dramatically impact music and composition and style in modern Eastern Arab art and popular music. To these two composers we can add Elias Rahbani, the younger brother born in 1938, who worked with them on occasion. And then, finally, Ziad Rahbani who was born in 1956, who is the son of Assi and Fairuz—as we’ll see, they married—and who remains her current composer. Each of these brothers have sons as well who became famous composers and composer poets, but these four are the ones who have really worked with Fairuz, and the Rahbani brothers, these two brothers in particular, Assi and Mansour, are the two with Fairuz who really launched this phenomenon.

Fairuz’s work has been nearly exclusively with the Rahbani family of composer poets, and so let me also provide some quick facts on these composers. They’re a family, the Rahbani family, and they hail from Antilyas, which is north of Beirut, and have an Orthodox Christian background, and the first two of them, you might say the primary two, the ones who, together with Fairuz, really launched the whole phenomenon, are two brothers: Assi and Mansour. Assi Rahbani was born in 1923 and died in 1986, and Mansour was born in 1925 and died in 2009, and the two of them were brilliant composer poets and artists in very large senses of the words. And they went on with Fairuz, as a team, to dramatically impact music and composition and style in modern Eastern Arab art and popular music. To these two composers we can add Elias Rahbani, the younger brother born in 1938, who worked with them on occasion. And then, finally, Ziad Rahbani who was born in 1956, who is the son of Assi and Fairuz—as we’ll see, they married—and who remains her current composer. Each of these brothers have sons as well who became famous composers and composer poets, but these four are the ones who have really worked with Fairuz, and the Rahbani brothers, these two brothers in particular, Assi and Mansour, are the two with Fairuz who really launched this phenomenon.

So, Fairuz, as a phenomenon, came up at the same time in a sense that the modern state of Lebanon came up, and this trio of Fairuz, Assi , and Mansour, they really resonated with Lebanese and with Arabs across Arab society.

Lebanon’s History

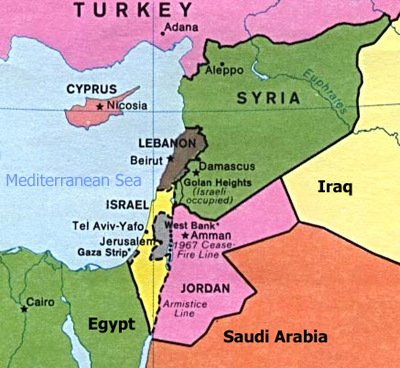

So, a quick look at Lebanon, I think, would help. It’s a small country with a giant history. I’m on the Central Coast here in California, and Lebanon is about the size of San Luis Obispo County, not much larger. It’s very small, about 4,000 square miles. And the history is long and multifaceted and rich, and the beauty is legendary. The beauty is written about in the Jewish scriptures or Old Testament Christian scriptures. The mountains are fabled and are called “The Lebanon.” That’s where the modern country gets its name. And these mountains meet this fantastic Mediterranean coastline, and there are perennially snow-capped mountains within eyeshot of the beach. And so a classic saying is that you can be sitting on the beach reading a book in the sun in a bathing suit and look up and see the snow capped mountains. It’s really fantastic.

The population of Lebanon is small. There are only about four million people there. At present, the religious makeup, generally speaking, is about 60% Muslims and 40% Christians. Historically, there also was a sizable population of Jews and a Christian majority. Throughout history, colonial empires have been attracted to the desirable location. It’s a very strategic location at the eastern edge of the Mediterranean Sea, and to this day, there is a striking legacy of Roman and Phoenician ruins that, if you were a child, you might grow up playing in; they’re just part of the neighborhood.

And so there’s been an enduring impact on the region, on Lebanon, on society, and on Fairuz and the Rahbani composers from the various reigns of power over the millennia. The Byzantine Empire lost control of what is now Lebanon to the quickly expanding Islamic Empire in the 7th century. That set the stage for the multifaceted religious demographic that’s continued to the present. The changing rules included the invasion of the Crusaders in the 12th century, the Mamluks in the 13th century, and the Ottomans in the 16th century. And then, the varying shifting allegiances between occupiers and occupied sometimes included marginalized religious groups in Lebanon, for example, the Maronites, the Shiites, and the Druze. And they were able to find refuge in these mountains that were so rugged that invaders found them very difficult to penetrate. If you were to see pictures, they’re these wonderfully rugged and beautiful mountains, and so, they were a safe haven as it were—not for the faint of heart. And so their ability to protect themselves in this way also helped to contribute to the ongoing diverse sectarian makeup of what is now Lebanon.

[caption id="attachment_13214" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Beiteddine (Turkish palace in Lebanon) Eyre, 2013[/caption]

Beiteddine (Turkish palace in Lebanon) Eyre, 2013[/caption]

While Lebanon was generally considered part of Greater Syria since ancient times, in the wake of World War I, France got the mandate over much of Greater Syria and established Greater Lebanon with its modern borders in 1920—in the mandate system where, in a nutshell, Western Europe carved up the eastern Mediterranean. And then Lebanon gained independence from France in 1943 and Arabic was and remains the official language, but there is still a significant amount of French spoken, as well as English and Armenian. And so this is the context into which Fairuz and the Rahbani composers were born and raised. And it’s not lost on them, just like it is not lost on their fans. That complex, cosmopolitan, multifaceted socio-historical background is just a part of who they are. And so when these artists came into their own, that’s what they brought with themselves and built upon. And, similarly, the audience base was ready to hear and receive in those terms.

[caption id="attachment_13260" align="alignleft" width="475"] Mansour and Assi Rahbani[/caption]

Mansour and Assi Rahbani[/caption]

Fairuz and the Rahbani Composers: Early Times

The Rahbani brothers—here I am speaking in particular of Assi and Mansour—they grew up hearing music at home. Their father played a long-necked, fretted lute, called a buzuq, at his coffee shop. So they would hear their father playing music and they would hear music at the coffee shop. And they also grew up listening to the prominent musicians of the time as any musicians would. And so, for example, Sayyid Darwish was one of the major, really formative composers and musicians of the day. He was born in 1891 or 2 and died in 1923. In his tragically short life, he had a dramatically big impact on modern Arab art and popular music. And so they were listening to his music, for example, and they would eventually go on to play some of his songs.

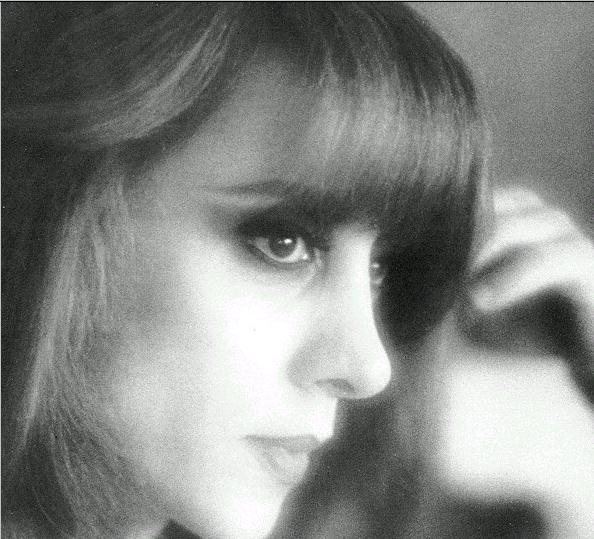

They were listening to Umm Kulthum, who was born around 1904 and died in 1975. They were listening to Muhammad AbdulWahhab, who was born around 1910 and died in 1991. And they were listening to Asmahan, the youngest of any of these I’ve mentioned, born in 1917 and died in 1944. And, as we’ll see in a moment, Asmahan would play into the inception of Fairuz’s career.

[caption id="attachment_13217" align="alignleft" width="248"] Umm Kulthum[/caption]

Umm Kulthum[/caption]

And so the Rahbani brothers began participating in local music and theater productions, and they studied music formally. They studied music with Father Boulos Ashqar, born around 1881 and died in 1962, and with Bertrand Robillard who died in 1964. And, so, with their studies, they developed their theoretical and compositional skills, not only in Levantine Arab art and popular music, but in Western European art music, which really fit well with who they were and understood themselves to be. And again that would turn out to work exceedingly well with their fan base.

In our personal interview in 1999, Mansour Rahbani was looking back and spoke about their artistic relationship. He said, “I can’t imagine finding two people whose names would be melded into one like the Rahbani brothers. There was no Assi; there was no Mansour. Sometimes, I wrote and composed and arranged the orchestration; sometimes Assi wrote, composed and did the orchestration; sometimes I would write and Assi would compose, then I would do the orchestration and vice versa, but the name was always the Rahbani brothers.”

So, indeed, they always signed their name “The Rahbani Brothers,” and in Arabic, it’s actually “The Two Rahbani Brothers.” Regardless of who was writing words or music or orchestrating or what, they were really a team and a kind of a package. They were composers and they were lyricists, but they were also playwrights and they were concert producers and they were studio producers and they were arrangers and orchestrators. They were doing a whole package, and I don’t know how much time I’ll have today to go into other composers that they drew upon in their work with Fairuz, but even in those cases, they generally retained oversight and remained the primary producers. And sometimes that didn’t go over particularly well with other composers who wanted more of a say.

I mentioned, for example, that they drew upon the work of Sayyid Darwish. Now, Sayyid Darwish had passed away, so there was no problem there with any ideas he might have had. However, when they drew on the work of living composers—for example, the legendary composer, Muhammad AbdulWahhab composed songs for Fairuz—the Rahbani brothers retained a certain production oversight. And that didn’t necessarily go over well with other composers because artists, being who they are, like to make their own artistic statements. But from the standpoint of the Rahbani brothers, what that enabled them to do was really take extra care with what it was they wanted to say in what I have called this Fairuz phenomenon that really happened as a result of this trio.

Fairuz’s talent for singing was recognized early on in her life. She was singled out in elementary school to sing in ceremonies at school and to sing anthems, and she received an award for having the best voice in the school. So, when she was very young, about twelve years old, in 1947, Muhammad Flaifel, who was a vocal instructor at the Lebanese Conservatory, heard her singing in a concert at school and invited her to join the conservatory to develop her skills. It was under his wing that she began developing particularly rapidly and studying vocal technique and musicianship, and also Qur’anic recitation to help develop her pronunciation with Arabic, which in Arabic song is crucial.

Now some might ask how it is that this Christian girl would be studying the Qur’an to learn  how to pronounce well. But there is such a long history in Lebanon of a multi-religious coexistence that there isn’t a reason not to, and the systems that are in place for studying the Qur’an make it fantastic. And, as we’ll see, her performers, just like her fan base, were always a wide spectrum of ethnic groups in Lebanese society. It made perfect sense, really.

how to pronounce well. But there is such a long history in Lebanon of a multi-religious coexistence that there isn’t a reason not to, and the systems that are in place for studying the Qur’an make it fantastic. And, as we’ll see, her performers, just like her fan base, were always a wide spectrum of ethnic groups in Lebanese society. It made perfect sense, really.

Fairuz began performing with Muhammad Flaifel, and that involved performing at the Lebanese radio station. And it’s the Lebanese radio station that I sometimes like to say is where it all started, in a sense. It’s at the Lebanese radio station where Fairuz met Halim Al-Rumi, who was the head of the music department. At his invitation, she auditioned and is reputed to have sung a mawwal (a vocal improvisation on poetic text) made famous by Asmahan and part of the song, "Ya Zahratan Fi Khayali" (O Flower of My Imagination), by Farid al-Atrash, the famous singer, oud player, and actor, who was the brother of Asmahan. And so Al-Rumi hired her to sing in the radio station chorus.

At this point, Fairuz is just going into her teens, and Al-Rumi adopts her as his protégé. So now she’s working in the Lebanese radio station. She’s really a kid and she’s working around masters, veteran musicians. Now, doubtless, she has a gift of an amazing voice. That’s the nature part. But then there’s the nurture part; even somebody with a great gift has to have it brought out. And she is now in a perfect context for this. Al-Rumi continues training her, and instead of having her go on to be called Nuhad Haddad, he suggests an appellation for her. There are actually a number of appellations on the table and she ends up going with “Fairuz,” which means turquoise, and it stuck and, in a sense, the rest is history.

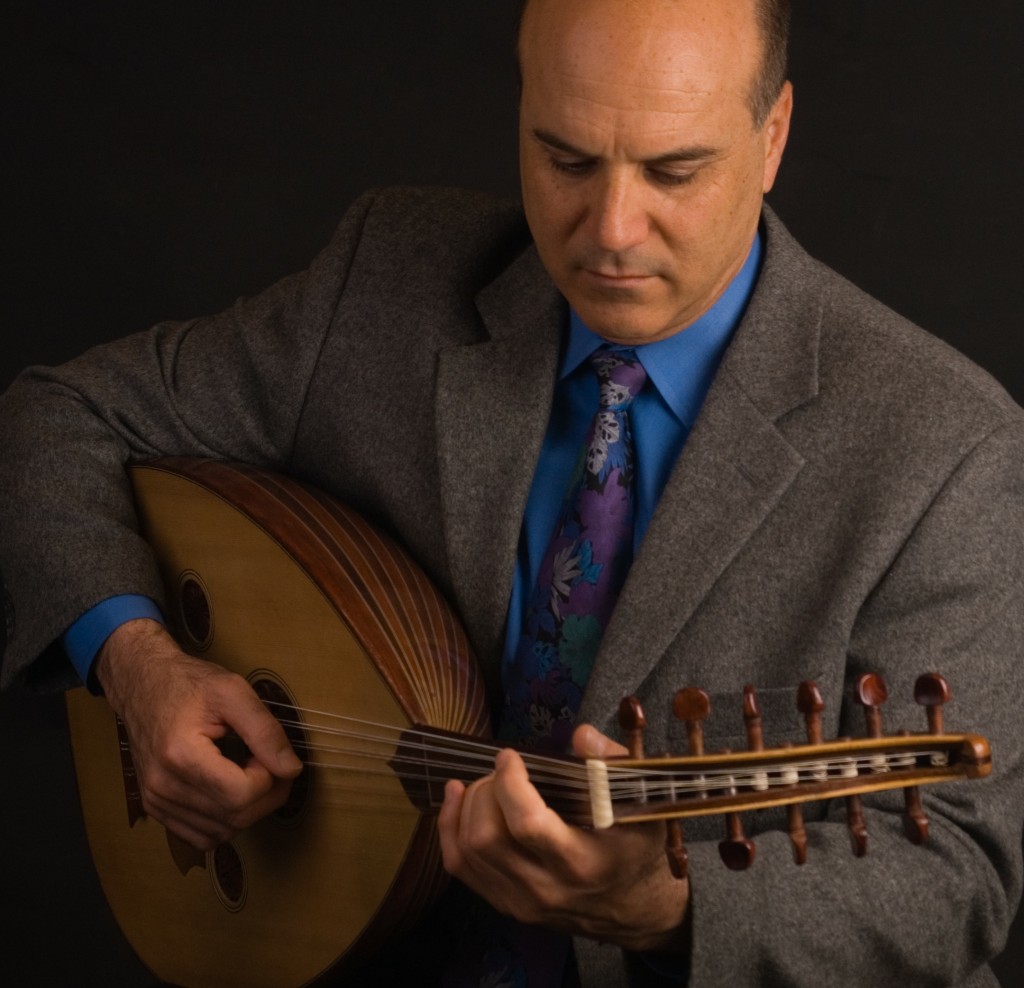

[caption id="attachment_13288" align="aligncenter" width="598"] Ken Habib with oud (Bob Lawson)[/caption]

Ken Habib with oud (Bob Lawson)[/caption]

The Trinity

It’s here at the Lebanese radio station where Fairuz and the Rahbani brothers meet. Al-Rumi introduces them. It’s in 1949 and she’s still a young teenager, and they’re only in their 20s. And they began working increasingly as a team. This collaboration at the radio station is what I would call “the second period” in their careers. The first period was when they were working professionally apart from each other. Once they were brought together here at the radio station, something legendary began unfolding. It’s the beginning of what is so substantive on artistic and sociological levels. And I would reiterate that the makeup of the musicians and the other involved parties at the radio station was multiethnic, and this was part of the pan-societal appeal that they would go on to have.

So, advancing a few years, in 1952, they achieved their first major hit across Arab society, and that was "ʻItab" (Blame). And it begins:

“You keep blaming me, and I have had enough of blame.”

And then the song goes on and it ends:

“How often I have said that tomorrow my heart shall repent and denounce your love.

I could never do it, my love. This heart could never repent.”

For the most part, it was a very traditional tune. It didn’t break any molds. It didn’t make any huge new strides. It was another tried and true tale of unrequited love. And it worked really well. But from there, they really took off stylistically and lyrically. One of the big contributing factors to the success of this trio was that there was great equipment at the various radio stations. At this point, they are working between Beirut, Damascus, and Cairo, which are three big urban centers of a shared art music tradition in the eastern Mediterranean. And these stations, these studios, had excellent, up-to-date equipment, and that’s something that can be heard. The quality that comes across can be appreciated.

For the most part, it was a very traditional tune. It didn’t break any molds. It didn’t make any huge new strides. It was another tried and true tale of unrequited love. And it worked really well. But from there, they really took off stylistically and lyrically. One of the big contributing factors to the success of this trio was that there was great equipment at the various radio stations. At this point, they are working between Beirut, Damascus, and Cairo, which are three big urban centers of a shared art music tradition in the eastern Mediterranean. And these stations, these studios, had excellent, up-to-date equipment, and that’s something that can be heard. The quality that comes across can be appreciated.

And, so, in 1955 they were working in Cairo and recorded the song, "Rajiʻun" (The Returning Ones), which was widely understood to be supportive of the Palestinian cause. And so, to give you a sense of the beginning, it says:

“In the rain we are returning, in the storm we are returning,

In the sun, in the winds, on the fields, on the plains we are returning,

In faith we are returning, for the homeland we are returning,

On the sand and in the shade, on the trails and in the hills we are returning.”

From “Rajiʻun” on, they would be identified with the Palestinian cause quite a bit. For example, in 1972, there is a whole album called Jerusalem in My Heart. They would continue to do pieces that would be understood to be supportive of the Palestinian cause. "Sanarjiʻu," similar to "Rajiʻun," is We Will Return. One of the fantastic epic pieces on Jerusalem in My Heart is "Zahrat al-Mada’in," or The Flower of Cities, which is understood to be Jerusalem. And so there would be all these references to the Holy Land appealing to audiences across Arab society.

And, similarly, as we’ll see, there was a horrible civil war in Lebanon, and these songs were then in a sense poised to be reinterpreted by the public as Lebanese themselves returning to their homeland after they had gone—if they could go—fleeing the horrors of war there. So, I would say it’s one of the central attributes of their art that they were able to appeal across the spectrum of society regardless of religion—the three big Abrahamic faiths, Islam, Christianity, and Judaism—without offending anyone. That was really central to their art.

Festivals and Folklore

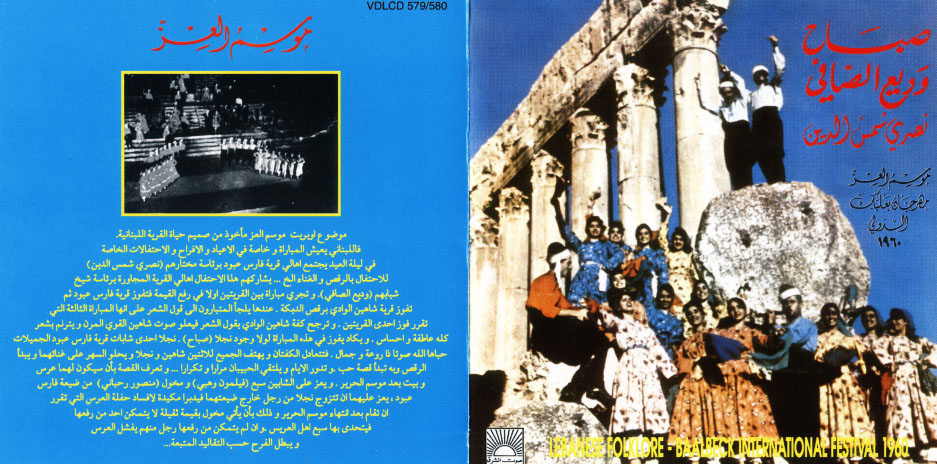

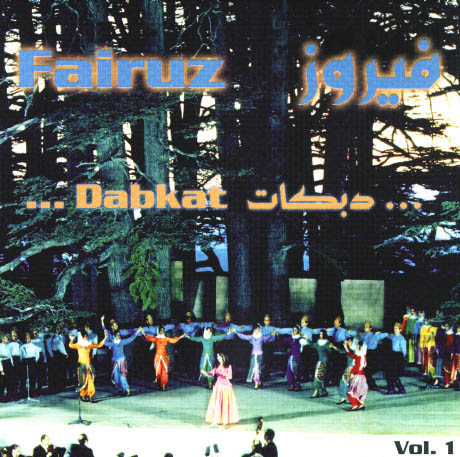

So, if we move ahead a little bit, we enter into another phase of their careers. In 1957, Fairuz and the Rahbani brothers began performing at what would become this iconic festival in Lebanon, the Baalbek International Festival. And it was a festival that focused on music and theater and dance, and that aimed at having an international appeal. And instead of performing in studios, where they were performing live but not in front of audiences, now they were in front of live audiences and, of course, that dramatically changes the dynamic. In their case, it was a fantastic match. While this involved concertizing, starting with the beginnings of the Baalbek Festival they also would produce some 21 musical plays or operettas—these sort of light but very rich and musical plays, or “singing plays,” as they’re called in Arabic.

So, if we move ahead a little bit, we enter into another phase of their careers. In 1957, Fairuz and the Rahbani brothers began performing at what would become this iconic festival in Lebanon, the Baalbek International Festival. And it was a festival that focused on music and theater and dance, and that aimed at having an international appeal. And instead of performing in studios, where they were performing live but not in front of audiences, now they were in front of live audiences and, of course, that dramatically changes the dynamic. In their case, it was a fantastic match. While this involved concertizing, starting with the beginnings of the Baalbek Festival they also would produce some 21 musical plays or operettas—these sort of light but very rich and musical plays, or “singing plays,” as they’re called in Arabic.

And these plays would draw upon local and regional sociopolitical history; they could be interpreted along sociopolitical lines. They would poke fun at colonial powers. They would weave fun, intelligent musical tales into some of their best hits. These hits are steeped in high art music traditions, but they’re also eminently popular songs. The art and popular music traditions of the eastern Mediterranean are much more closely connected than they are, for example, here in the States. And so they are hugely popular—in a sense more popular than anything we have here because they literally do appeal across the sociological spectrum. Although we’ll see that that changes as the decades go on. But the early work appeals across lines of age, religion, class, geographical place—and so it’s gigantically popular, but also deeply rich art music. So they have this theatrical material and they’re also recording albums live and performing in festivals in Damascus and in other places.

They’re drawing upon their cultural background, which is really cosmopolitan and multiethnic and multifaceted and rich, and bringing it into their music making, and their audience loves that. And it fits into contexts like Baalbek, which wants to have an international appeal. And it also ties into a kind of construction of modern Lebanese identity in this time where Lebanon is, in most people’s views, setting sail into a kind of a golden era. And the Rahbani brothers bring a compositional style not only steeped in Levantine art music, but in western European art music, and in particular French art music. And they’re also drawing upon American popular music, particularly Latin music and jazz. But they’re doing it in such a way as to infuse those styles into something of their own. And this is really received by most as something Lebanese. In fact, these productions at Baalbek were called “the Lebanese Nights.” And so it was at this time that Lebanon was called “the Switzerland of the Middle East” and people called Beirut “the Paris of the Middle East.”

[caption id="attachment_13249" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Stage set at Beiteddine Festival (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

Stage set at Beiteddine Festival (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

So, in addition to marrying together art and popular music, they were also drawing extensively upon folk music and religious music of the region. For example, the team was famous for producing many examples of dabke, this line dance, famous in the eastern Mediterranean, and ʻitaba and other kinds of folk music. They would tie this into their musical plays in masterful ways that would help the story line unfold because these plays often unfolded in village settings. And so it would sometimes be comical, it would sometimes be serious, but practically always it would be effective. And sometimes you would hear chanting music traditions come into play, whether it was Byzantine or Maronite or what have you. The Rahbani brothers were masterful in the way that they did this compositionally. And, at the same time, Fairuz, really, as a singer, was masterful in her ability to handle the wide range of material that they gave her.

In our interview in 2002, Mansour was reflecting on the many diverse cultural forces that they themselves experienced, and then expressed in their musical productions with Fairuz, and he went on to cite “Arab musical culture, Byzantine, Syriac, Muslim, Turkish, Armenian, Assyrian, western European classical music, and American popular music.” Those were his words.

So, for example, in the hugely popular hit, "Khidni," or Take Me from the musical play Return of the Soldiers, recorded in 1962, the lyrics themselves provide an excellent example of the evocation of imagery associated with friendly, rural, folky, agricultural village life from the perspective of one who longs to return. So even in concert performances decades after, when Fairuz performs this song, the atmosphere becomes solemn and weighty, and there is a sense of expectation. The lyrics refer to rural life and the landscape and fruits and the very ground of the village and animal life and neighbors and friendship and Lebanon itself and the sky and prayer; it’s tying all of these things together. It says:

So, for example, in the hugely popular hit, "Khidni," or Take Me from the musical play Return of the Soldiers, recorded in 1962, the lyrics themselves provide an excellent example of the evocation of imagery associated with friendly, rural, folky, agricultural village life from the perspective of one who longs to return. So even in concert performances decades after, when Fairuz performs this song, the atmosphere becomes solemn and weighty, and there is a sense of expectation. The lyrics refer to rural life and the landscape and fruits and the very ground of the village and animal life and neighbors and friendship and Lebanon itself and the sky and prayer; it’s tying all of these things together. It says:

“Take me into its beautiful hills

Take me out into the land that raised us

And forget me there, among the terraces of grapes and figs

Shed me upon the grounds of our village

Ancient doors are beckoning me

And the sound of the rivers are driving off the absence

And eyes at windows are shouting to me

‘Friends,’ you’re saying, ‘we’re friends’

And I walk in forgotten alleyways

A world that is setting and birds are about to pass the night

I anticipate some hand that is shaking mine

Some voice that is saying, ‘good evening’

Take me and plant me in the ground of Lebanon

In the house that’s guarding the hill

Where I’ll open the door and kiss the walls

And I’ll kneel under the loveliest sky

And pray.”

[caption id="attachment_13215" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Lebanese countryside (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

Lebanese countryside (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

The song itself is a kind of a musical adventure. It starts very traditionally, and there are drones that aren’t necessarily religious but that do help to bring about a certain solemn air. The accordion is one of the instruments that entered eastern Arab art music and that the Rahbani composers completely embraced in their orchestra. And, similarly, the piano, and generally speaking the piano is used to color the atmosphere just as we hear in the beginning of "Khidni." As we get to the end of the tune, we hear some relatively complex harmonic changes leading to this a cappella section. It sounds almost church-like as Fairuz sings “take me and plant me in the ground of Lebanon.” And it’s this really powerful, solemn moment, and you hear the lone a cappella voice of Fairuz, and the audience knows it’s coming and wants it to come, and erupts in applause as the line unfolds.

Music that Transcends Division

Like other stars of the day, Fairuz starred in films. These films were created and controlled by the Rahbani brothers, and they were careful to make them what they wanted them to be. The three films that she starred in were Biyyaʻ El-Khawatim (The Seller of Rings) from 1965, Safar Barlik (The Exile) from 1967, and Bint El-Hares (The Daughter of the Guard) in 1968.

In addition to the operettas and these films, she also has recorded religious repertoire for Easter and for Christmas. She has performed in Good Friday chanting traditions yearly throughout her career and, so, one of the things that I would say is that she’s perceived to be a religiously devout person and, I think we can say, fundamentally a good person. I think that’s a major part of her artistic appeal. I can’t tell you how many people have told me she is like a model for them and how many people have told me that she is ----- have used terminology like “sacred ground.” And her Good Friday services are attended not only by Christians, but by Muslims and Jews, regardless of religious background.

In addition to the operettas and these films, she also has recorded religious repertoire for Easter and for Christmas. She has performed in Good Friday chanting traditions yearly throughout her career and, so, one of the things that I would say is that she’s perceived to be a religiously devout person and, I think we can say, fundamentally a good person. I think that’s a major part of her artistic appeal. I can’t tell you how many people have told me she is like a model for them and how many people have told me that she is ----- have used terminology like “sacred ground.” And her Good Friday services are attended not only by Christians, but by Muslims and Jews, regardless of religious background.

I think a common misconception is that religions somehow were very separated. That’s not always so much the case. I don’t mean to paint an overly rosy picture of how everyone always got along. But historically, people lived together, for the most part, really quite fine. So, Muslims, Christians, and Jews went to school together, did business together, shopped in the same stores, were friends, had dinner in each other’s homes, and that sort of thing. It’s more the aberration, what happened in the civil war, where all of that broke down. And that, we can see, is the product of an enormous complex of pressures that, in a way, “little Lebanon” just wasn’t able to sustain. That the Lebanese weren’t at fault at all—that’s not what I am saying. But I would say that the separation of people was really more the aberration whereas the coexistence of people was more the norm historically.

Civil War

The civil war was infamous, from its inception in 1975 to around 1990, when it sort of sputtered to an end. With it, there was the unequivocal disintegration of whatever was perceived to be this golden era. The civil war certainly stemmed from a complex of factors. There was a history of foreign meddling in this tiny place of Lebanon, fomented in part by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. There has been a presence of a huge population of disenfranchised Palestinian refugees since the creation of Israel in 1948, and these Palestinians have not been given citizenship on the principle that they should be allowed to return to their homes. And the presence of Syrian and Israeli forces in the country over the years, and the increasingly inequitable system of sectarian power balance in the country also contributed. And, so, the war unfolded in a convoluted way along religious lines despite that pluralistic history. And people who were formerly friends, for crazy reasons, found themselves barricaded in their own neighborhoods, shooting at their friends, barricaded in the next neighborhood over and, again, in a fairly small space.

And, of course, Fairuz responds to the war. By this point, Fairuz has become an icon of Lebanon, and that means different things to different people. That couldn’t be clearer than in the civil war, when everybody continues to embrace Fairuz, even though their ideologies clearly differ from each other. Fairuz is going to suffer the war at the artistic level, as well as on the individual and social levels where everybody else is suffering. So there are a number of ways that she responds to the war: she responds with repertoire; she responds by refusing to perform inside Lebanon, except for the Good Friday services, which in and of itself makes a certain statement about devotion and where priorities lie. And, at the same time, she continues to tour outside of the country. So, for example, that 1981 tour of the United States where I first saw her is one of her particularly famous tours.

Though she was touring outside Lebanon, she continued to live inside the country when she certainly was well off enough to leave. She could have fled to safe haven but she didn’t. I can’t tell you how many Lebanese people have told me that this was a time when she “withheld her voice from us.” It was almost, in a sense, punitive. She withheld her voice.

And, so, in 1976 came the album B-Hibbak Ya Lubnan, or I Love You Lebanon. It  includes the song of the same name. The song describes a love of nation that extends in all directions; she is really further bolstering this iconicity with the country that has developed. She speaks of a love of nation that extends in all directions, that persists in the best and worst of times, that doesn’t waver in the face of madness. She and the Rahbani composers directly address the war in terms of its armed conflict and those who fled to other places, even though they didn’t. And, of course, it brings in the very value of the soil of Lebanon, the ground, you know, the attachment to the place. I will read the lyrics. They are powerful:

includes the song of the same name. The song describes a love of nation that extends in all directions; she is really further bolstering this iconicity with the country that has developed. She speaks of a love of nation that extends in all directions, that persists in the best and worst of times, that doesn’t waver in the face of madness. She and the Rahbani composers directly address the war in terms of its armed conflict and those who fled to other places, even though they didn’t. And, of course, it brings in the very value of the soil of Lebanon, the ground, you know, the attachment to the place. I will read the lyrics. They are powerful:

“I love you Lebanon, my homeland, I love you

In your north, in your south, in your plains, I love you

You ask what’s with me and what’s the matter with me

I love you Lebanon, oh my homeland

With you I want to remain while the absent ones are away

I’m tormented and distressed, how sweet is the suffering

And if you leave me, most precious of friends

The world will turn into a lie and the crown of the earth to dust

In your poverty, I love you, and in your prosperity, I love you

And me, my heart is in my hand—Your heart will not forget me

And the evening at your door is more precious than a year

I love you Lebanon, oh my homeland

They asked me, ‘What is happening in the land of feast days

A cultivated land circled with gunfire and rifles?’

I told them, ‘Our country is being created anew

Lebanon, the noble and its strong-willed people’

However you are, I love you—With your insanity, I love you

If we became separated, your love would bring us back together

And a grain of your soil is more precious than the treasures of the world

I love you Lebanon, oh my homeland.”

And so you can see the team of Fairuz and the Rahbani brothers were not afraid to address the war head on. The war continued to unfold in ways that really didn’t solve any of the underlying problems and even exacerbated them, and left people wondering why it had happened and what good possibly could have become of it. Most people were just trying to get by while the war unfolded, while Beirut was to a great extent crumbling. It was physically devastated. To this day, there are buildings that remain pocked with holes from the gunfire and bombs. And the Green Line that marked the dividing line between so-called East and West Beirut ran down the center of the city. The East and West parts were construed to be Christian and Muslim, which was to some degree real and to some degree not.

The Peace Concert

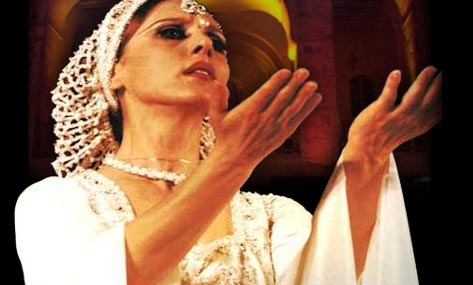

A period of reconstruction followed the war. Fairuz reemerges to perform in Lebanon. In 1994 there is a concert that becomes famous as “the Peace Concert.” And where does she do it? She does it on the Green Line, which is the symbolic center of the whole conflict. And, in particular, it’s at Martyrs’ Square, this geographical heart and powerful symbolic center of the war. It’s a square that’s dedicated to the martyrs. I think there are a number of these in the region. These are the martyrs who historically suffered and died to throw off the shackles of colonial oppressors and to gain independence and self-determination. So it’s powerfully symbolic at many levels.

There is a quote in one of her concert programs from 2003. She oftentimes has these deluxe concert programs. This comes from L’Expresse and beautifully describes the event. So these are the words of Jacques Girardon: “In the heart of what was the downtown, this unique city, the crossroads of East and West, of Islam and Christianity, a giant concert with 50-thousand people from all confessions. And the same desire of peace and nostalgia for the golden years of Lebanon before the war. It could be only Fairuz who was able to bring all of Lebanon together to celebrate the end of the seemingly endless and extremely  destructive civil war.” And he goes on to say, “In the moonlight, we could almost see soldiers’ shadows holding kalashnikovs, standing on the top of destroyed buildings. Sea breeze moist and heavy, inflated the sails and transformed the stage into a Phoenician vessel. When the musicians began to play, the audience held their breath. And then, Fairuz appeared. She planted herself and stood immobile and strong like a cedar, and she sang for the 50-thousand gathered at her feet and for the 200-thousand ghosts of the war.”

destructive civil war.” And he goes on to say, “In the moonlight, we could almost see soldiers’ shadows holding kalashnikovs, standing on the top of destroyed buildings. Sea breeze moist and heavy, inflated the sails and transformed the stage into a Phoenician vessel. When the musicians began to play, the audience held their breath. And then, Fairuz appeared. She planted herself and stood immobile and strong like a cedar, and she sang for the 50-thousand gathered at her feet and for the 200-thousand ghosts of the war.”

I’ve read that so many times I can’t tell you, and every time I do I get goose bumps. The number of people that were disappeared—Who knows what happened to them? We don’t know that they died or they didn’t die. We don’t know that they’re still in prison somewhere. We don’t know what happened to them. This is one of the painful unresolved legacies of the war.

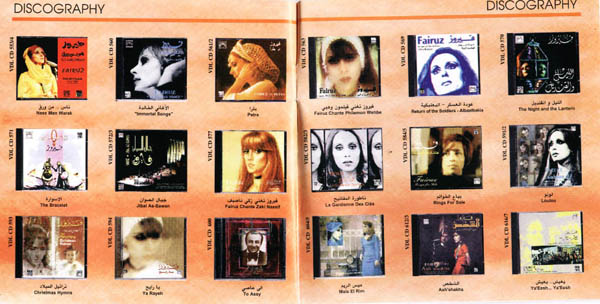

If there is a recording of this concert, I don’t know of it. I haven’t talked a lot about her repertoire, but her discography of official releases is some 110 albums with some 1700 commercially available recorded tracks. It’s prodigious by any estimation. There are duplicates with compilation releases and that sort of thing, but most are unique pieces. The repertoire is gigantic, spanning from the 1940s to 2010, traversing technology that goes from four- to eight-track tapes, to 78s, 45s, 33s, and cassettes, and CDs and MP3. Mansour Rahbani himself would tell you that they don’t know themselves exactly how many songs they’ve done. Every day, that is just what they did. They’d go into the studio; they’d perform. It took on a life of its own.

[caption id="attachment_13254" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Ziad Rahbani (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

Ziad Rahbani (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

The Era of Ziad

So if the war was its own period in the careers of Fairuz and the Rahbani composers, the reconstruction started another, hopeful phase. It was also a more realistic, and perhaps austere, phase with a shift in style—with Ziad Rahbani, coming from another generation, at the center, and with Fairuz getting older and stunningly able to remain agile as she adapted to Ziad’s developing style. She was really remarkable in that respect.

So, to recap, Assi died during the war in 1986. Ziad becomes the primary composer for Fairuz. Ziad began composing for Fairuz when he was only 16, in 1973 when his dad Assi was in the hospital and Ziad received the opportunity, and also the responsibility, to compose a song for the operetta that was in work, Al-Mahatta, or The Station. And so he wrote this great hit, "Sa’alouni Al-Nas" (The People Asked Me), with the support of his father and uncle, Assi and Mansour. This piece has been widely interpreted as being about his ill father and the public asking about his father and his well being. It unfolds like this:

“The people asked me about you, my love

They wrote letters and the wind took them away

It’s painful for me to sing, my love

And for the first time we’re not together

People asked me about you, they asked me

I told them, ‘He’s returning, please don’t blame me’

I shut my eyes fearing that the people

Would see you hidden in my eyes

And the wind rose up and love made me weep

And for the first time we’re not together.”

As I mentioned, anything that Assi and Mansour did together in whatever relation was in  the name of the Rahbani brothers. So I think we understand that Mansour wrote the lyrics but Ziad wrote the music. And the music is really right out of the stream of the Rahbani brothers. So imagine Ziad growing up the son of Fairuz and Assi Rahbani, with his uncle Mansour Rahbani, who is half of the composing team of Assi and Mansour Rahbani, and his uncle, Elias Rahbani, who also worked with them. He was surrounded by geniuses who likewise were working with geniuses.

the name of the Rahbani brothers. So I think we understand that Mansour wrote the lyrics but Ziad wrote the music. And the music is really right out of the stream of the Rahbani brothers. So imagine Ziad growing up the son of Fairuz and Assi Rahbani, with his uncle Mansour Rahbani, who is half of the composing team of Assi and Mansour Rahbani, and his uncle, Elias Rahbani, who also worked with them. He was surrounded by geniuses who likewise were working with geniuses.

And, so, this is not at all to take away from Ziad; Ziad actually turned out to be brilliant too. But in that nature/nurture dynamic that I mentioned earlier he, like his mother Fairuz, had the opportunity to be raised around these amazing veteran musicians and composers. And so, basically, where he picked up at 16 years old is right where his family delivered him in this ongoing family music culture. I think it could scarcely be overstated the significance of the fact that we have a family here. Now I don’t know the intricacies of how it all worked, but Fairuz and Assi were husband and wife, and Ziad was their son. They were just in each others’ space a lot. So, if ever as a composer, you want to say, “Hey honey, would you sing this? I want to get a sense of how it’s going to sound exactly?” or vice versa: “Hey honey, I don’t really like the way this fits in my voice.” The opportunity for that kind of exchange is extraordinary. And so Ziad is born into this, and you could say that he takes the baton and runs with it, and you hear this is "Sa’alouni Al-Nas." You hear this really great piece of catchy popular music that’s completely rooted in the art music of the region.

So Ziad has this ability to produce in this style of the lineage of the generation of the Rahbani brothers, but he’s also a generation younger and he has the sensibilities or the viewpoints or what have you of someone a generation younger. And sometimes that rubs the older generation the wrong way. He’s a socialist, for example. That didn’t and doesn’t go over well with some, but his musical genius is undeniable.

One thing we didn’t mention is that Fairuz and the Rahbani composers are working in the  formal register of Arabic a lot, but they’re also working extensively in the Lebanese dialect of Arabic, and, less so, in other dialects of Arabic too. And so, that’s one of the ways they’re showing their mastery and increasing their appeal. Ziad concerns himself primarily with Lebanese Arabic and Lebanese culture and he establishes himself with his own musical plays and he also clearly undertakes an interest in jazz per se.

formal register of Arabic a lot, but they’re also working extensively in the Lebanese dialect of Arabic, and, less so, in other dialects of Arabic too. And so, that’s one of the ways they’re showing their mastery and increasing their appeal. Ziad concerns himself primarily with Lebanese Arabic and Lebanese culture and he establishes himself with his own musical plays and he also clearly undertakes an interest in jazz per se.

One of the things that Ziad ends up bringing to the table in his work with his mother, Fairuz, is these more outright jazz stylings and also more austere, non-romantic lyrics. This is doubtless due in part to his more socialist beliefs and to what he saw his country go through as it disintegrated from what people had reveled in around the world. Lebanon really was a place where people across the Middle East would go to find relatively liberal culture and enjoy the nightlife, and where the intelligentsia would go, and where artists would go, and spies would go, and all kinds of things would happen.

So he’s bringing all of his experience and sensibilities into his music, and one of the places where we can see that sort of all come to pass is in his song, "Bizakker bil-Kharif" (He Reminds Me of Autumn). It’s on the album Wala Keef, or Nor How from 2002, and it is his rendition of the standard, “Autumn Leaves.” It begins with a classical jazz free introduction with completely rewritten lyrics by Ziad in Lebanese Arabic before taking off into the tune and continuing with all new lyrics:

So he’s bringing all of his experience and sensibilities into his music, and one of the places where we can see that sort of all come to pass is in his song, "Bizakker bil-Kharif" (He Reminds Me of Autumn). It’s on the album Wala Keef, or Nor How from 2002, and it is his rendition of the standard, “Autumn Leaves.” It begins with a classical jazz free introduction with completely rewritten lyrics by Ziad in Lebanese Arabic before taking off into the tune and continuing with all new lyrics:

“I remember you each time the sky gets cloudy

Your face reminds me of autumn

You used to come back to me at nightfall

And blow like a gentle wind

It is not a matter of weather, darling

It is a matter of a violent love story.”

Legacy

So, looking back on the whole thing, I think we can say that Fairuz and the Rahbani composers crafted an artistic style, a musical style, but going beyond music itself, a body of work that aimed to be particularly Lebanese and to contrast with more Egyptian styles of eastern Arab art and popular music, while at once appealing across Arab society from Morocco in the west to Iraq in the east, and from Syria in the north to Yemen in the south.

Also, reconciliation is something that Lebanese have yearned for since the civil war, and this is where Fairuz and Ziad have been working as a team since its close. Fairuz herself reflected with somewhat of an optimistic tone in her 2003 deluxe concert program this way:

“The most important thing is that the war is over and that people are going to meet each other. It is going to take time. There are those who like each other; here are those who hate each other. But something is going to start at this concert,” referring to that peace concert. “There is already a return to the gentle ways of the past. Those who come to the concert know that. We will march on with our past. We will form something new. Life will continue. The city will be revived.”

Now that has not happened nearly as quickly as anyone would have liked, but again, in Fairuz’s words, in an interview with Nelda LaTeef, she reflected this way: “When I sing patriotic songs like, for example, ‘I love You Lebanon,’ I have seen Muslim and Christian militia men who days earlier were fighting each other on the streets, standing in the aisles with tears streaming down their cheeks, hugging each other and singing the words to the song along with me.”

Now that has not happened nearly as quickly as anyone would have liked, but again, in Fairuz’s words, in an interview with Nelda LaTeef, she reflected this way: “When I sing patriotic songs like, for example, ‘I love You Lebanon,’ I have seen Muslim and Christian militia men who days earlier were fighting each other on the streets, standing in the aisles with tears streaming down their cheeks, hugging each other and singing the words to the song along with me.”

And so she, like everybody, I think, is hoping and working within the sociopolitical circumstances that exist to strive toward this future that is equitable and tolerant and hopeful. I would love to be able to say that the war is over and everything’s getting better, but in 2006, for example, there was the Israeli-Hezbollah war, and Israel invaded the country again.

So, it might be hard not to imagine Fairuz’s comments as being overly idealistic. Fairuz comes from a generation with perhaps a certain amount of idealism built into it, and that is very attractive to people. But I think in Lebanese people’s hearts, there really is the glimmer of hope, not necessarily for a return to the past—that’s not going to happen. But I think people still find in the work of Fairuz a kind of hope for tolerance, enjoyment of life and pluralism of culture. And they retain that hope for their lives and the lives of generations to come.

At this point, Fairuz is advanced in years, though she is still singing and concertizing and recording and so forth. I would say, though, that there is no one poised to take her position in almost any way—at the level of vocal artistry, command in the larger sense of the singing art that’s produced, and perhaps even in the sense of hope that has been engendered in her song. But, at the same time, everybody still hopes and longs for that.