Photos by Marilena Umuhoza Delli

Ian Brennan is a Grammy-winning producer, whose set of recordings on the Zomba Prison Project in Malawi put his work on our radar, and was featured in the Afropop program, “Off the Beaten Track in Malawi and Burkina Faso.” He is a fearless producer who has illustrated, along with his wife, filmmaker/photographer Marilena Umuhoza Delli, his ability to take on projects that put marginalized communities at the forefront. He travels the world looking for stories from those on the fringes of society and encourages moving songs straight from the hearts of people with little or no professional music training and explores the feelings of loneliness, love and heartbreak that resonates with people all over the world.

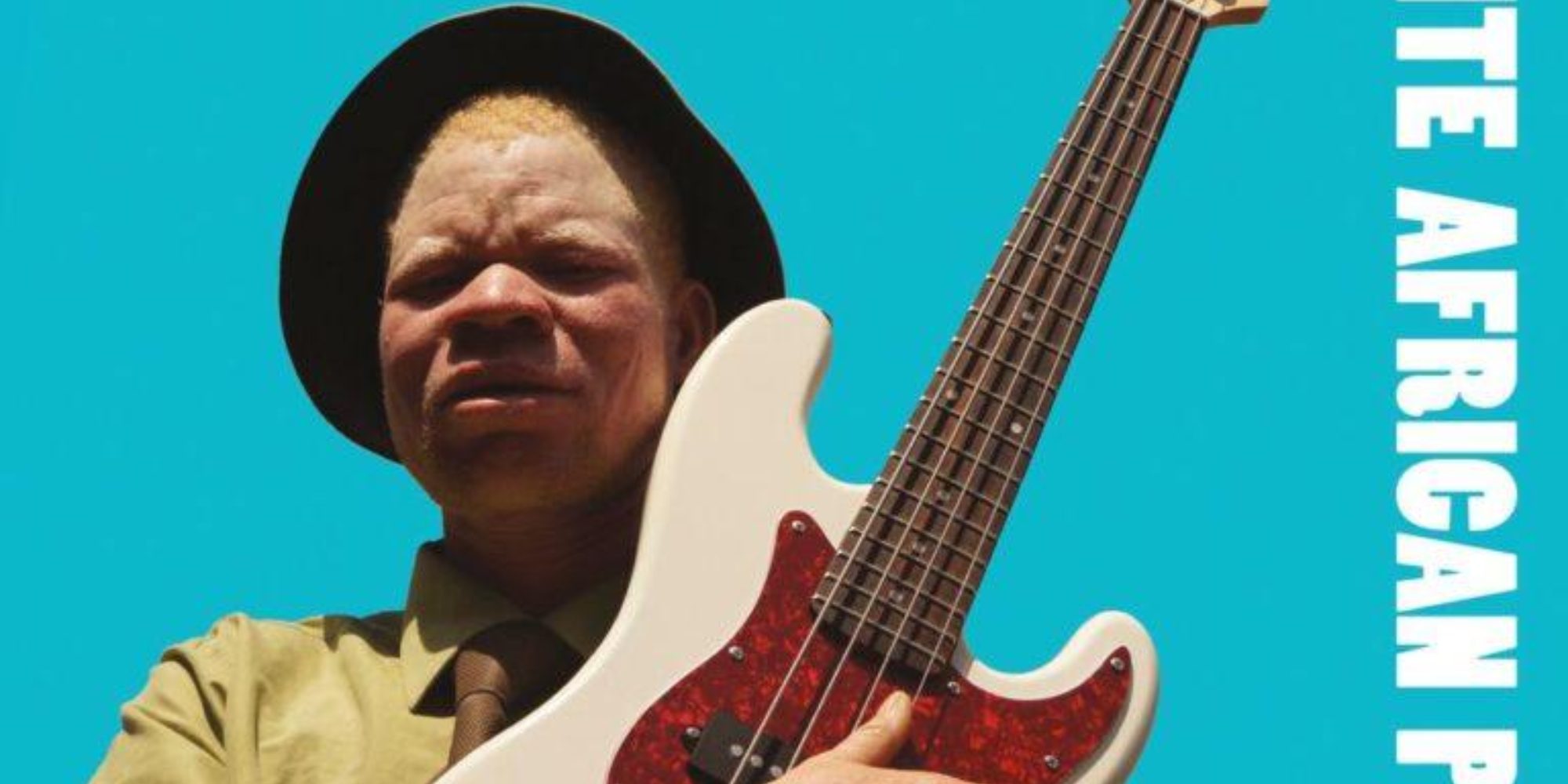

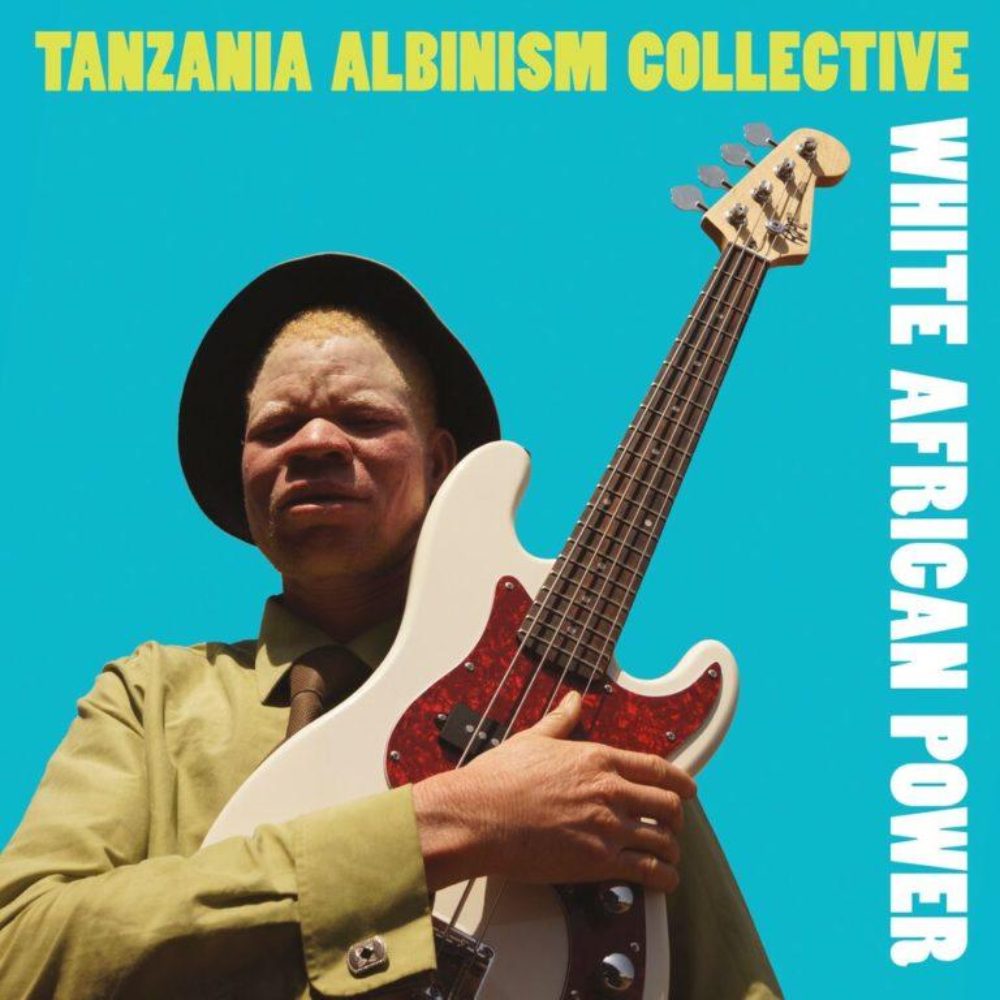

His latest project, White African Power, out now on Six Degrees Records, features the voices of those living with albinism who have found refuge from persecution with the Standing Voice community on the island of Ukerewe in Tanzania. The lack of pigment in the skin of those with albinism has made it very difficult for them to live in African societies such as Tanzania, where they are hunted due to the belief that their body parts hold magical powers. The horrors they face simply because of their skin color are atrocious, which emphasizes the audacious and empowering act of naming the album White African Power, a title selected by members of the Albinism Collective. This album features 23 uplifting and emotionally devastating songs, all just over a minute long, sung in Kikirewe and Jeeta. The songs are avant garde, raw, and some utilize unconventional instruments like dueling school table-tops for toms, a sledgehammer snare, and a beer bottle and nail cowbell. The album was released on June 13, International Albinism Awareness Day, and is available here.

In addition to music production, in 2016 Brennan published his fourth book, How Music Dies (or Lives): Field Recording and the Battle For Democracy in the Arts, in which he explores the purposes of music and how it can enact social justice. I had the pleasure of hearing Brennan speak on the topic of social justice at the New School in New York, and the subject was the focus of our subsequent phone conversation back in March. This topic is on the minds of many arts organizations at a time when government funding and support for the arts is being seriously threatened, and elicits discussion of how to get involved and use resources and methods as efficiently as possible. Ian is passionate, very opinionated, and at times controversial about his chosen weapon to enact social justice: music, and more specifically, roots folk songs.

Akornefa Akyea: Thank you for making the time to talk to us.

Ian Brennan: Of course. I love what you guys do. It’s important.

I wanted to talk to you more about social justice in music, which was a topic you touched on at the New School and in your book How Music Dies (or Lives): Field Recording and the Battle For Democracy in the Arts. In your words, what is art’s true purpose?

I think the original intent is music. I think it’s necessary to people’s spiritual health. It’s not necessary for their day-to-day survival, but I think for long-term survival physically on the planet it helps. It’s the original and sometimes best antidepressant and sexual enhancer. [Laughs] Music is really powerful and it’s really good. And I think that ultimately art is designed to change us neurotically and challenge us and unfortunately the corporatization of media does exactly the opposite. It limits people’s possibilities. It makes them think the world is smaller in the worst sense of the word rather than the good sense of the word, meaning people being connected, and it causes people to not be challenged and also to see difference as something that is negative and kind of painful. I think there are a lot of folks where you name certain genres of music or when you talk about foreign film or books, they associate that with pain, and that’s probably a failing of the education system too.

Can you expand on what you mean by “they associate that with pain?”

The thing that people say all the time is “that’s hard,” like it’s hard to watch a foreign language film. You have to read all the subtitles but I think it’s an incredible source of nutrition that people are denying themselves. I use that analogy a lot between nutrition and art. We are kind of built to like stability, to resist change, but the beyond the initial change it gets better. If you learn to appreciate vegetables more, if you learn to eat better, you start to crave and like those things. But initially people go, this kale salad is horrible, but I feel like with music and arts, it’s often a lot of the same. It’s not even that it’s philosophically correct. It just seems like a missed opportunity. It’s questionable until not that long ago, every major city, every college town from the neorealist explosion in film in the 1950s, they had foreign-language cinema theaters that you could go to and support enough that they could be viable. They weren’t making huge amounts of money but there was a platform where people could find the hot foreign-language film of the moment. Of course that would usually come from industrialized countries, but nonetheless, at least people were going beyond Hollywood and getting beyond their own borders, so to speak.

I’m curious about what you think of the genre “world music” and what that does for world musicians, since some of the music you produce has been categorized as world music.

I don’t like the term world music and I don’t like any genre really. I think the best artists and strongest artists don’t play a genre, they play themselves so you can’t put them in a genre. You can say Billie Holiday was jazz but no, Billie Holiday was Billie Holiday. She wasn’t playing jazz, she was playing her entire life and that’s why she resonates today and as long as people listen to recorded music she will, because it’s so vibrant and fully realized and true and honest and authentic.

As you know, the biggest danger of the term world music is it creates an “other.” It creates a center and of course the center is the Western world which isn’t even physical: it’s the U.S.A., Canada, England, Australia, and increasingly other nations as well. Basically it’s whoever is rich and everyone else is kind of outside that, and I think that’s really philosophically and politically a bad thing, but I also think it’s not correct. I think when people start reducing nations down to single artists, it’s a very scary thing, you know? A litmus test I use with people sometimes is to say, well, what do you think about Brazilian music? And it’s kind of a trick question because they’ll say, well, I like it or I don’t like it. But how can you like it or not like it? It’s this is a massively diverse country. The right answer, the healthiest answer psychologically would be to say I like some of it. It’s not for lack of musicmaking, it’s wrong, it’s illogical, and it’s simply not true. You go to pretty much any country in the world and people are making music and even releasing music within their own borders to whatever degree that they’re able. But in general I don’t like the term world music.

Do you have any suggestions for what it could be called? Or would you prefer for people to just call it what that genre of music is as opposed to putting it under the umbrella of world music?

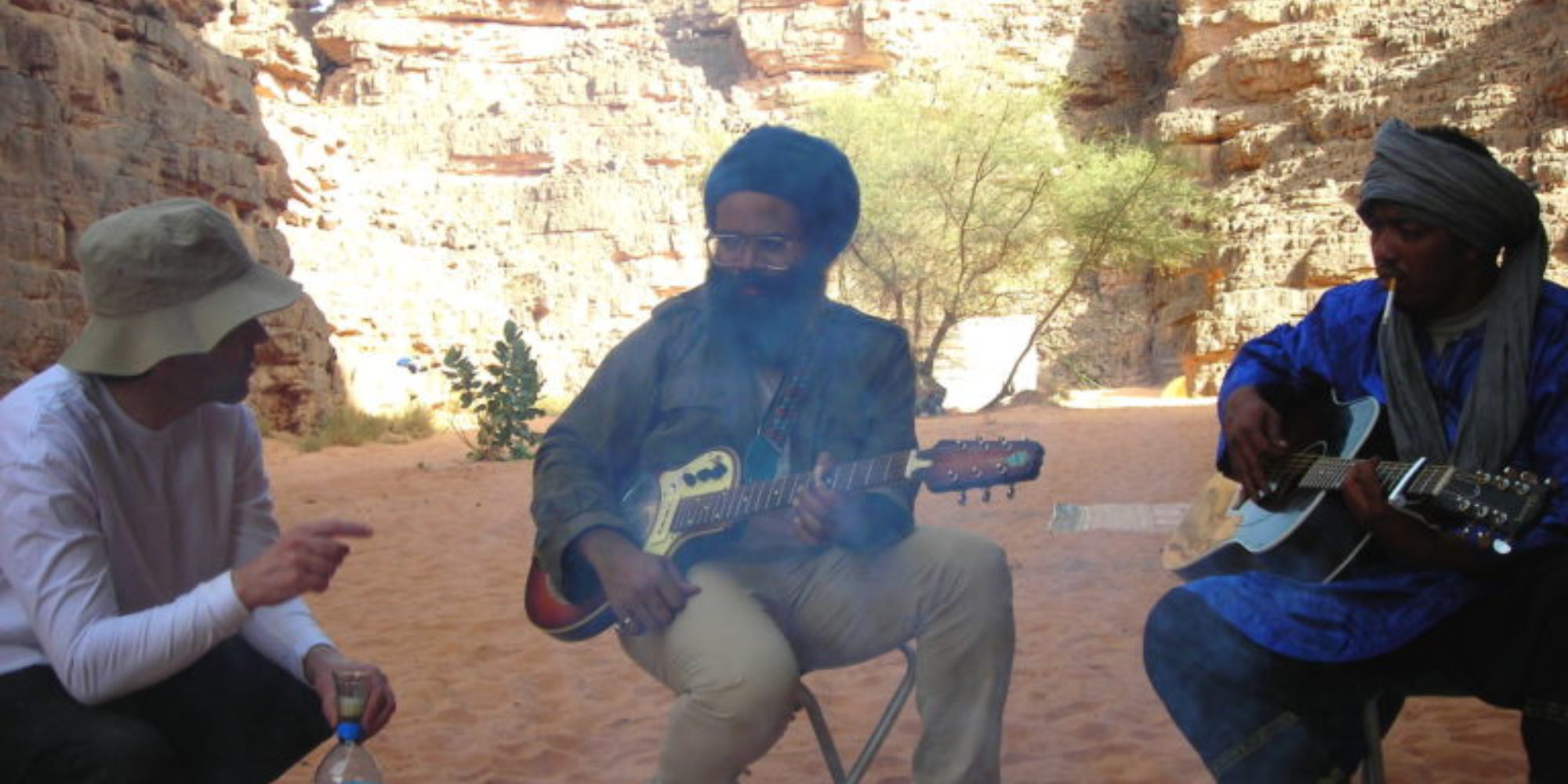

Exactly. I think it’s a little of both. I would love if you went into the international section of a store like that and they had a slot for every country on earth. So it’s not world music but you go there and you could hear what music from country “X” sounds like. Hopefully there would be multiple records and not just one artist to define the entire country and maybe they’re not even within the same historical thread of the music or even that similar to the other artists. So that would be one thing but even better, and maybe it’s even more idealistic, but it’s exactly what you said is that I think everyone should be treated equally, and artists should be seen as what they are, not where they’re from, and that’s been my big beef with Tinariwen. From day one before we did the record, I came in with the perspective that we’re making a guitar band record. We need to make this about songs and not about jams. We need to approach it like we would if we were doing a record with the Flaming Lips or one of the great few guitar bands left. And so that’s been a challenge. It’s really hard for people to see past the outfits, so to speak.

Is social justice at the forefront of the projects that you take on and what you do? How does that weave through your consciousness while you’re working?

Yeah, it is at the forefront. My wife, Marilena Delli, and I choose nations that we feel are underrepresented with pop music–not field recordings from the 1950s–in their own language. So not somebody from the country who moved and is a first-generation immigrant singing in English, which is great and awesome. I have nothing against that either but to be clear, a record in Kinyarwanda, not a record from someone from Rwanda living in Toronto singing in English. They are two different things. We do that deliberately and sadly it’s very easy to do. Meaning there are so many countries that are underrepresented. Then in the country in general I think so many people’s interests should shift from the myth of race, because there is no race just the human race, and begin to focus on class and see the destruction that is caused by those divisions that aren’t talked about as much as they should be and also those commonalities in each culture. So yes, it’s very deliberate when we go to Rwanda or South Sudan or Malawi or Vietnam and do these records. But in the end, as a producer my goals are very different. My goal is songs and people that are specific in their writing and voices I feel are unique. I think the songs should stand on their own. What they have in general that a lot of world music does not have–and I don’t think it’s a fault of the rest of the world, I think it’s the fault of the people promoting world music and that are involved in the production of world music and the appropriation of world music– is usually it lacks melody. It usually lacks songs. So there’s this overemphasis on the “exoticness” of it or the groove and the jam, as opposed to–wait a second, how about just awesome timeless melody? I’m not anti-anything but for me I think the tried and true idea of the world music business/industry–whatever you want to call it–is the song is everything. The songs are what transcend.

I’m wondering if you got any pushback or criticism from black people in Africa or the diaspora from doing the project?

I think that these are by design modest projects, and my goals are modest, and everything I do I approach with love which starts with the love of music. I’ve had a love affair with music for as long as I can remember. I started playing guitar when I was 5 years old and I was obsessed with art, particularly with music, and a love of people. I had to start supporting myself as a teenager and I had to do that by working in psychiatric settings. I’ve done violence-prevention training since 1993, and I’m able to make enough money from that and I have a little left to make these projects that make a little money. So I talk to strangers in their most vulnerable and intimate spots in their life—about things they would not usually talk to people about, like suicide, addiction, psychosis and abuse. This has, oddly, probably helped with interacting with people all over the world. Because to me it is about intimacy. Aside from the songs and melody, I’m trying to achieve intimacy for the listener. I think it’s very important that the listener goes to the artist and not the other way around. Because I think historically the whole history of appropriation and this idea of treating people like they’re different or exotic and putting them on a pedestal is very strange, delusional, inaccurate and is really unhealthy. It’s always been about making the artist come to where the center is. Come to New York or come to London. I try with the record to make people feel like they’re there and you’ve got to meet that person where they’re at.

But to answer the question about pushback, I mean there has been–I’m always braced for that, I’m not the right person to be doing this stuff on paper. But I really believe in individuals. I believe we need to talk about individuals, we need to talk about class much more than we talk about race. Race unfortunately is a hugely damaging, and real thing even through it’s not real it is, and it affects people’s lives and even ends people’s lives, and it has done so for so long tragically, but I think in the end it comes down to individuals. But I know on paper, I’m very cognizant that I’m not the right person to do that. I would say conversely my wife, Marilena, maybe is one the “right people” to do it. She’s Italian-Rwandan raised in the most racist part of Italy with an African immigrant mother from Rwanda who survived three genocides, so I mean she might be the right person to do it. So the pushback I would say has never ever come from any artist we’ve ever worked with. The pushback in general, if at all, does come from the gatekeepers of world music or it might come from the Caucasian or Western individuals who are very ready to protect other people they’ve never met and maybe don’t understand the dynamics of.

I think there are a lot of people in this country who have some sort of privilege whether it’s class or race. For people who are interested in getting into social justice work–whatever their medium is–whether that’s music, journalism, law, etc., do you have any other suggestions for those people who want to get more involved?

My orientation is very different, for better or worse, than academics and ethnomusicologists from decades of working in social service and music. I don’t have that formalization. My thing is probably a little bit more wild. And it is certainly more D.I.Y. It makes it unique. But again it’s about the relationships, intimacy and voices of the individual and that they’re telling their truths with their voices. So my advice, and I don’t know if anyone would want my advice…

I’m listening!

[Laughs] O.K.! My advice is the same as with writing–that is, be specific, be specific, be specific, be specific. And that means work small but with impact. So it’s that idea, you’ve got $300,000 but what are you doing with that $300,000? Because if only $5,000 of that is going to really do what it should, then somebody with $5,000 can do the same thing and they don’t need a grant. I think people should look at where the need is and sow the seed. Meaning there’s kind of these beaten paths and everything else gets forgotten. An example from my mother-in-law’s life–a lot of people may not know this but there were three genocides and she survived all three in Rwanda–in 1959, 1973 and 1994. Almost nobody knows about the 1973 and 1959 genocides. They weren’t big enough. Most people don’t know, and why would you? There’s so much going on in the world. There’s so much tragedy, almost too much to keep track of. But even so, you have this genocide and tons of resources and everybody that’s contributed and tried to contribute should be applauded, and it’s made a difference in that nation since 1944, but it’s so odd because there were these other genocides too, and how can you call something small? How can you call a country small? There is no small country in the world. How can you call a genocide small? Even if it’s 100 people, it’s 100 people! It’s insane. So I would try to encourage people to go where the heat isn’t. O.K., where is the path not beaten? Where are there needs that are being overlooked and where is the utility? What can I do with my $50 or $1,000?”

I think that’s very sound advice. Thank you so much.

Thank you.

Related Audio Programs