On Sat., April 22 at Dobbin St. in Brooklyn, members of the Puerto Rico-based band ÌFÉ mounted the stage dressed humbly yet magnificently in all white and positioned themselves behind their respective percussion instruments. The event was hosted by Cosa Nuestra, the Puerto Rican culture collective that showcases all facets of Latin culture with a focus on its African heritage. ÌFÉ, which translates to “love” in Yoruba, performs songs composed and produced by bandleader Otura Mun, who uses his devout practice of the religion Ifá--a divination practice with roots in West Africa--to inform his music and message. The music, much like Otura Mun, is a cohesive unit, yet clearly made up of many different and seemingly disparate parts: They sing in English, then Spanish, then Yoruba, fluidly interchanging Germanic, Latin and West African languages with otherworldly electronic sounds juxtaposed against the grounded and resonant drums. Their sound is at once stripped down and at the same time full.

Mun’s unique background is the obvious root of the many different sides that make up the music of ÌFÉ’s debut album. He is an African-American man born and raised in Indiana who relocated to Puerto Rico where he has resided since the late 1990s and is a babalawo (priest) of Ifá. Akornefa Akyea caught up with Otura on the roof of Saturday’s venue to discuss the three singles from ÌFÉ’s latest album: What the symbolic representation of their new album IIII+IIII means, how it’s pronounced, and to gain an understanding of Ifá from the perspective of ÌFÉ.

Akornefa Akyea: Congratulations on the new album! I'd like to discuss the three singles with you and to focus on a different aspect with each of them. I want to discuss meaning in “3 Mujeres,” imagery in “House of Love,” and decolonization in “Bangah.”

Otura Mun: Awesome.

In “3 Mujeres” when they say “Iború, Iboya and Ibosheshé,” what is the meaning of that?

"Iború, Iboya and Ibosheshé" is a greeting that we as babalawos give to each other when we meet and see each other. It’s also a greeting that our initiates inside the religion give to a babalawo when they meet us. If we are babalawos and we meet each other in the street it’s “Oyé! Iború, Iboya and Ibosheshé!” That’s the greeting that we give to each other. As initiates, if they meet me in the street and they’re already initiated, they touch the floor and they say “Iború, Iboya and Ibosheshé” as a sign of respect. Those are actually the names of three women and the story comes from the pataki which is associated with a divine destiny or odu [verses that are linked to signs] inside of the corpus of Ifá and the story.

The corpus of Ifá being the guide?

Ifá being…There are sort of two houses inside of what some people call Santería, which is rooted in the Yoruba practice in the Caribbean. The two houses are Ochá deal with Orishas de Fundamento and those are orishas like Obatalá, Oyá, Oshun, Changó. Then Ifá deals with the divination side of the religion and we work with the orisha Orunmila. People that are babalawos or priests of Ifá are thought to be direct descendants of the orisha Orunmila. Our job is divination on the highest level. Odu are signs that can be divined inside of the Ifá corpus. There are 256 signs and each sign has a whole body of poems and epic stories about what happens inside of that sign and each sign is thought to be a divine destiny that the orisha Orunmila has already lived. If you’re going to come to a consulta with a babalawo, I’m going to pull out a sign, divine a sign that is active or is manifesting in your life at this particular moment and we’re going to talk about what that sign means for you at this moment and whether you’re living a positive or negative expression of that sign. If you’re living a positive one, we’re going to try to see how we can lock that positive energy in and if you’re living a negative expression of that sign, we’re going to try to see if what we need to do to get you aligned in a positive manifestation.

Is it possible to have both positive and negative?

No.

You have one that you focus on?

Yes. We see if you’re living a positive manifestation of that sign which is called iré, or negative which is called osogbo. Either way we try to help you to align yourself either stronger or completely with that particular sign. The idea being if you’re living in harmony with that sign and that energy you will have things like wealth, success, good relationships, long life, etc. And if you’re out of harmony with that divine destiny you are going to have conflict, loss and on down the line. So going back to what you were talking about, in terms of meaning, there’s a story inside this corpus about these three women, and a babalowo is traveling to a sort of dangerous kingdom. On the way he meets each woman and each woman gives him a warning about what may be coming up the road for him. Her name was Iboya. The next woman gives him another warning about what may be coming up the road: Iború. So Iború, Iboya, Ibosheshé, the three women kind of combine to give him this prophecy about what he’s going to meet at the very end of the trip. That’s how the name comes together. So you have Iború, Iboya and Ibosheshé, the names of these three women combine into this greeting that we now use in modern day.

Photo of Otura Mun by Melissa Quiñonez.

Photo of Otura Mun by Melissa Quiñonez.

For this album, the sign or odu that was picked is Eji Ogbe (IIII+IIII)?

Yeah, that’s the title of the record and eji ogbe is the first sign of the 256 signs. It’s the king of the signs. When that sign comes out in divination one of the things that it means is spiritual awakening. Another thing that it means is coup d’état. In Spanish we would say a rey meurto, a rey puesto—you are going to see a change in the guard. It also could mean separation because the sign looks like two parallel lines that never meet. I liked the sign because you have two component elements on the right side and the left side. On the right you have ogbe and on the left side you also have ogbe and ogbe by itself means the purest light, open roads and the beginnings. So you sort of have double ogbe. The very first sign is the king and the beginnings. I liked it as a nice starting point but it’s also a revolutionary sign. And I think that some of the things that are marked inside of that sign are very pertinent to the day and the moment that we are living in right now. If you look at the cover of the record it’s a man with his hands up and there’s a cross in the middle sort of making a physical representation of what that sign looks like. It is also making a reference to “hands up, don't shoot” and the struggle of African Americans here. You know, it works on a lot of different levels and I thought it was a great place to start.

With “3 Mujeres,” I get the sense that everything in this album was done intentionally. When I hear especially female voices on this album, it always sounds very distinct. Is there a specific role that women play within Ifá and is there a way that it was represented in this album?

I don’t think that I tried to reflect on the role of women in this spiritual practice when we were recording the songs. I’m just a fan of big female choruses, period, as a producer and I went there. Truthfully, most of my friends are women and I’ve been working with another woman who sings with us on tour. She’s actually my best friend for at least 15 years. We’ve worked on music forever together. Her name is Yarimir Cabán. It was just a matter of great musicians and they were women.

In the video for the second single, “House of Love,” I see a lot of imagery and the practice of Ifá shown quite explicitly. What did you want to get across with that song and in that video?

The song itself I wrote from a personal standpoint. The first line of the song says “dime mi hermano, soy tu siervo” which in English would be “tell me my brother, I’m your servant.” So whoever is listening, and this is typical of many songs on the record, I’m trying to write in a very inclusive way about broader issues and I’m writing very specifically for people that understand what I’m talking about on some certain level. I’m writing in an overarching way so that people don’t have to know, for example, things that are ceremonial or characteristic of the religious practice in general or about my personal life. So “dime mi hermano” or “tell me my brother, I’m your servant” is a very human thing that you might say to someone in the sense of human interaction and helping each other and the idea of giving.

That’s very poetic.

Sure. I was actually writing for my brother who passed away. So I was telling him as my ancestor, tell me what you need from me in this world, in this place you’re at right now. I’m here for you. During this practice or inside this religious practice, there’s a way for me to commune with my ancestors and I do so on a daily basis. I have an area in my house where I offer things for them every morning and as I’m eating dinner I offer a little piece of my food. Every morning I offer coffee and a glass of water, etc. It’s a very real relationship where we’re talking to each other and having this interchange. So the hook of the song is, “something for you, something for me. Divine. True?” “Algo pa' ti, algo pa' mi, divino verdad que si?” It’s about that idea of giving to receive but in a very sort of personal way. In the third verse I say, “tell me grandfather, I’m your servant,” another ancestor of mine and my grandmother just passed away. On stage I say “dime abuelo soy tu servidor.” It’s like, the idea of not losing this connection we have spiritually with the people around us even in death. So that’s where I’m coming from. In Spanish you have a masculine and feminine way of saying things with words, so in the second verse I say, “te adoro eres única” which means “I adore you, you’re one of a kind” but I changed it to use a feminine verb ending so you think that I’m possibly talking about a lover or some woman maybe who is close to me that’s no longer reachable. But I really was still thinking about my brother. I knew if I changed the verb ending, I was going to open it up for more people to engage with that.

The subtext of the song which is in parenthesis is ogbe yekun, which is another sign in Ifá. So ogbe yekun is the sign I received when I initiated on the first level in Ifá and it’s a sign that completely balances light which is ogbe and darkness which is yekun: masculine and feminine; the beginnings and ends; birth and death. It’s the first time the signs combine: Ogbe (masculine) and yekun (feminine.) You see in the video a lot this contrast between light and dark, birth and death. Also the orisha that rules that sign is Oshun and I’m the son of Oshun. So what you’re seeing in the video is really the idea of me falling asleep, having a dream and my ancestors and the orishas telling me what’s going to happen in my life. They want me to continue and be crowned in Ochá. Oshun wants me to receive her. I need to pass over to Ifá so you see this moment where I have these seeds called inkines, that are used to divine, come to me. There’s actually a moment where I wake up inside of a circle with another woman there and I’m laying face up and she’s laying face down. That’s making the physical representation of the sign for ogbe yekun. The circle is making an allusion to the table that we use to divine as babalawos. You have a skull at the bottom, a cross at the top and the sun and the moon on either side which signifies life, death, beginnings and ends.

The animal that rules Oshun or is associated with Oshun is the peacock, so you see the peacock walking around. People that are aware of Oshun and her attributes immediately know what I’m talking about if they see the peacock. There’s a section where you see this woman shaving my head. That’s an allusion to being crowned or making saint inside the religion. There are all these little hints and signs that are going that on one level you may understand if you know about the religion and are initiated but there are other things that are there in terms of the universality of the themes that I think are also readable and understandable in some sort of way.

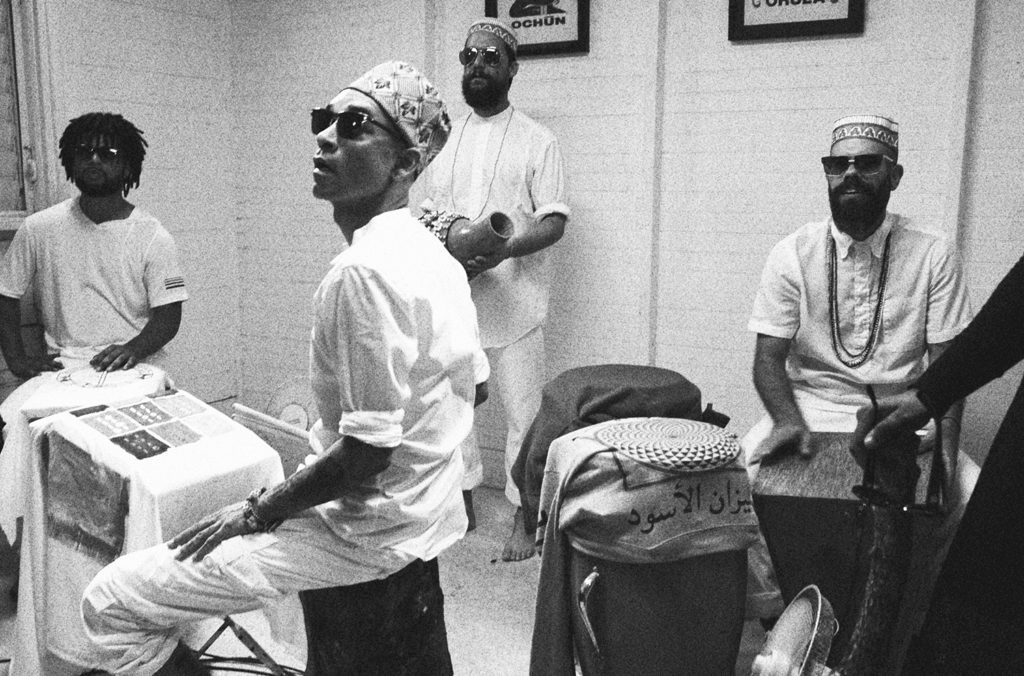

Photo of ÌFÉ by Mariangel Gonzales.

Photo of ÌFÉ by Mariangel Gonzales.

Wow. The last song and most recent single, “Bangah,” is described as a war cry. When you hear it there is a wonderful momentum to it. What type of metaphorical war does that represent?

Well, I mean "Bangah" was difficult for me. The name of the group ÌFÉ in Yoruba means love but it can also mean expansion. You have those two concepts that are the springboard of the group. I had the word before I had any of the music or knew what I was going to do but I tried to build it around the word. When I heard the beat for "Bangah" played I knew it was going to be a war song but I don’t believe in war as a method to solve human conflict. However, I do believe in conflict and conflict is real so when we think about war inside the Yoruba pantheon, the orisha that comes to mind first is Ogun because Ogun is the owner of war. I tried to think about Ogun’s role in my life, Ogun’s role in the lives of others and the general scheme of things. Ogun’s main tool is the machete, and maybe his secondary tool would be the anvil because he’s the smith in the religion. The machete also has a political connotation in Puerto Rico because there was a group of freedom fighters called Los Macheteros or “the machete guys” and they were the real-deal freedom fighters that believed in revolutionary liberty in Puerto Rico. I thought of Ogun as the divine machetero and wondered what that would be like. Another of his tools is the anvil and the word anvil in Spanish is el yunke but El Yunke is also the name of our national forest in Puerto Rico. So Ogun is also the owner of the forest. I’m just kind of running it down the line here. There’s another sort of Afro-Cuban practice called Palo which originated in Congo. They use the orishas and the energy from Ogun but they call it a different name which is Sarabanda. Ogun is also the owner of work and in the song I say “pico y palo.” Well, a pet name for work is “pico y pala” with an “A” at the end that just means banging out work but if you change it, it becomes “pico y palo” and people who know about Palo know that I’m making a reference to the Congolese practice of Palo and the main energy there is also Ogun-Sarabanda. The greeting in between people who are initiated in Palo is “As-salamu alaykum, waʿalaykumu s-salām”

Ah! I heard that in there, and that’s where that comes from?

Yup. That’s how they greet each other.

In Arabic?

Yup, because it’s sort of pre-Islamic Arabic. So that was something that was brought over through the transatlantic slave trade and it’s still there through this practice. And I believe it’s the same greeting for people that are practitioners of the same religion in Congo till this day.

So the last thing I’ll say about “Bangah” is that the hook of the song is for Ogun but it’s also sung during a ceremony called El Cuchillo or the knife ceremony. When you receive this knife, both on the side of Ochá and the side of Ifá, it marks an actualization inside the religion. It means that you don’t necessarily need your padrino (godfather) and your madrina (godmother) who trained you and taught you the religious practice to stand in front of the world. You can stand on your own. It’s the idea of personal liberty. In the song I say “dame el cuchillo” or “give me the knife,” give me freedom, give me liberty. I’m trying to think about what it takes to become free and for me it is with determination.

Ogun also lives in a caldron with another orisha named Ochosi. Ochosi is the hunter. He points at what he’s going to hunt, shoots it and Ogun clears the way to go get the animal. That’s how they can live together. The idea being that you name what you want and Ogun will clear the way because he’s the owner of work. We’re going to get there and we’re not going to stop until we’re dead and that’s the way you go get something. You have to be determined, fortify yourself and go get it. I think that works on a personal level and it works on a much larger level as well. So if we can free ourselves and understand how to attain freedom then we can apply that to any situation moving on up the board.

I hesitate to talk about what should or shouldn’t happen in Puerto Rico maybe on a political end because I don’t believe in a nation state. I believe a nation state is just a way to organize people to defend the interest of the rich and I don’t believe in borders and any of that. What I do believe in is freedom, and liberty and I want my friends and neighbors in Puerto Rico to be free. We need to get out of the thumb of colonialism because it is just destroying us, it’s been destroying us for centuries. We need to free ourselves and then from that point and that place, decide what it is we’re going to do.

Is there an audience that you want to cultivate maybe in five to 10 years time that you can make music for with even more pointed messages? Is there a movement or awakening that you want to spur with your music?

I would say no, I’m just trying to make music that hopefully will have a positive impact on people’s lives. If I can inspire someone and give a sense that things can change. Because overarchingly Orumila, the orisha that gave me the power to divine as babalowo, represents the idea of the possibility of change in the human soul and the human life for the better. A lot of time that comes from a spark of inspiration and the idea that I can change and this world that I’m living in can become better. If someone can walk away from this record with that in mind then I’ve done it. Ten years down the road, that’s all I can hope for.

Got it. Thank you so much and I look forward to watching ÌFÉ perform tonight!

You’re welcome!

IIII+IIII was released on March 31 on Discos Ifá and is available on Bandcamp.