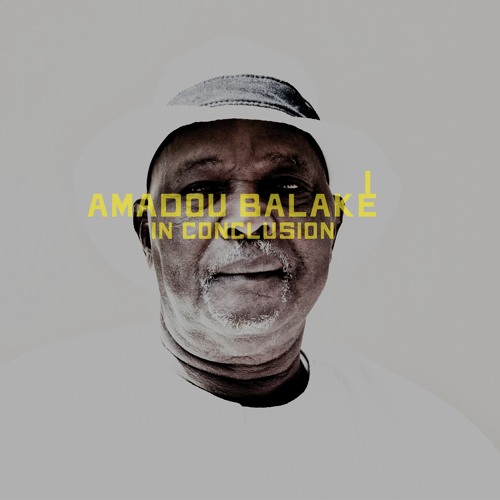

We don’t hear a lot from Burkina Faso, unless, as in recent days, there’s an outbreak of political instability. But here’s a voice from this dry West African nation we should know better. Amadou Balaké was born in 1944 and began his career young, traveling throughout the region as a singer and percussionist, recording albums and co-founding his own group Amadou Balaké et Les Cinq Consuls. He recorded in Paris and New York in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, and was one of many West African vocalists to sing songs with the Latin-African juggernaut Africando.

Balaké earned his nickname for his powerful rendition of the old Mande song, “Balaké,” reprised here in a lovely, spare arrangement featuring just one electric guitar and one ngoni. But his signature was a rhythm called warba, a rolling 6/8 groove from his ancestral village, wonderfully represented here on the track “Naaba,” which plays like a rousing, pentatonic hunter’s song.

This fortuitous session was created with the help of French music writer Florent Mazzoleni, who has published extensively on African music, and obviously holds a special affection for this under-recognized artist. I say fortuitously because Balake died at 70, barely a year after this recording was made. You sure would not know that based on these performances. Balaké has a strong but nuanced voice, capable of gale-force griot-belting, as on “Lamizana,” a song of praise to a former Burkinabé president. Turning on a dime, Balaké fades to a soulful near-whisper before surging again into august praise mode—very effective.

Elsewhere the singing can be rough and growling, equally thrilling in its way. This is the case on “Massa Kamba,” rooted in sweetly rolling balafon interplay and a propulsive 4/4 groove accented by warm brass melodies. The album opener, “Kambélé Ba,” unfolds in a marvelous 12/8 lope, again with balafon and brass as well as rich vocal harmonies, all in a dark tonality in which Balaké’s lead vocal exudes sage authority. A laughing, rapping section in the song hardly suggests a man at death’s door.

“Bar Konon Mousso” and “Oyé Ka Bara Kignan” present another satisfying face of Balaké’s musicianship—‘70s Afro-funk. It’s particularly fitting on the former song, which laments the difficult live of urban African musicians during the ‘70s. Sleeve notes on the latter song cite Afrobeat, but really, this is closer to the pre-Afrobeat funk of West African cities at that time, spare and hot, with vocal cries that echo James Brown, not Fela Kuti.

The song “Kélé Bila (Conflict Is Not Good)” was written in response to the 2012 crisis in neighboring Mali. The electric guitar intro is reminiscent of the old Rail Band of Bamako, and the other featured instrument on the track is ngoni, the preferred melodic instrument of Malian griots. Such attention to detail! In Conclusion is one of the best roots African releases of the year. Too bad so many of us are discovering this marvelous musician after he’s already left us. But kudos to Mazzoleni for giving us this important record of his work.