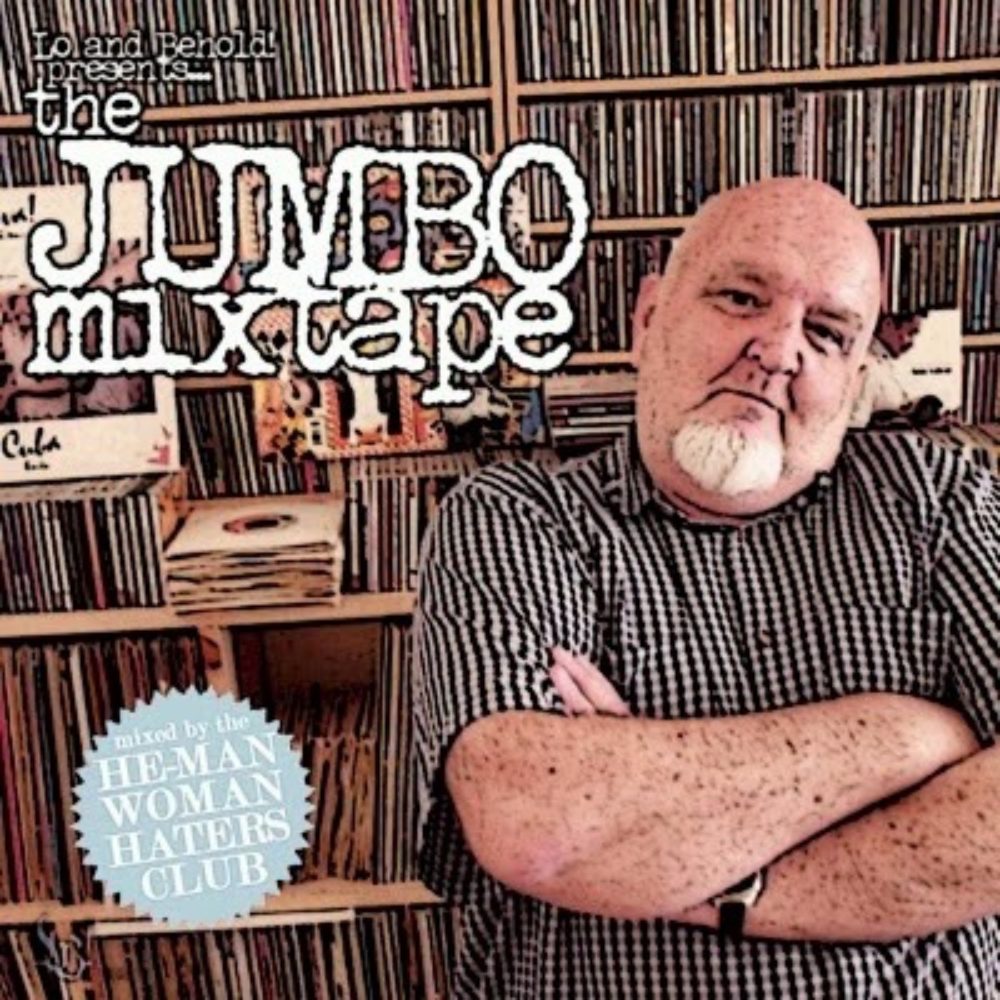

As the curtain falls on 2018, we remember the beloved musicians who died – all too soon – this year; and also a man who, though not a musician, did as much as anyone to introduce us to the contemporary music of Africa and the Caribbean: Donald “Jumbo” Vanrenen. If his name isn’t familiar, that’s probably because he was a modest gentleman who worked beyond the spotlight and away from the microphone, happily turning attention to the artists he admired. He was called Jumbo not only for his physical size but also for his huge knowledge of music, his expansive influence, and his big heart.

He was born in 1949 on a farm near Stellenbosch, South Africa. Although his family was white and prosperous, from a young age he was sharply aware of the injustices of apartheid, and (according to relatives, childhood friends and his own account) he hired lawyers to defend black neighbors who had been deprived of their rights and property. As a student at the University of Cape Town he made a point of reading every book that the government banned. His interest in music was sparked when he heard a Cape Town band, Malombo, led by guitarist Philip Tabane: that experience lit a flame that burned for a lifetime. Exploring the local jazz scene with his friend Trevor Herman whenever the color bar could be eluded, he attended gigs by Malombo, Dollar Brand (later known as Abdullah Ibrahim), and Ngozi Winston Mankuku. In a little shop around the corner from a train station, he and Trevor discovered records by “jive” musicians like Mahlathini and the Mahotella Queens, but it was impossible to get into township bars to see them perform. Indignant with how apartheid poisoned all aspects of life in South Africa, Vanrenen left his homeland as soon as he was able.

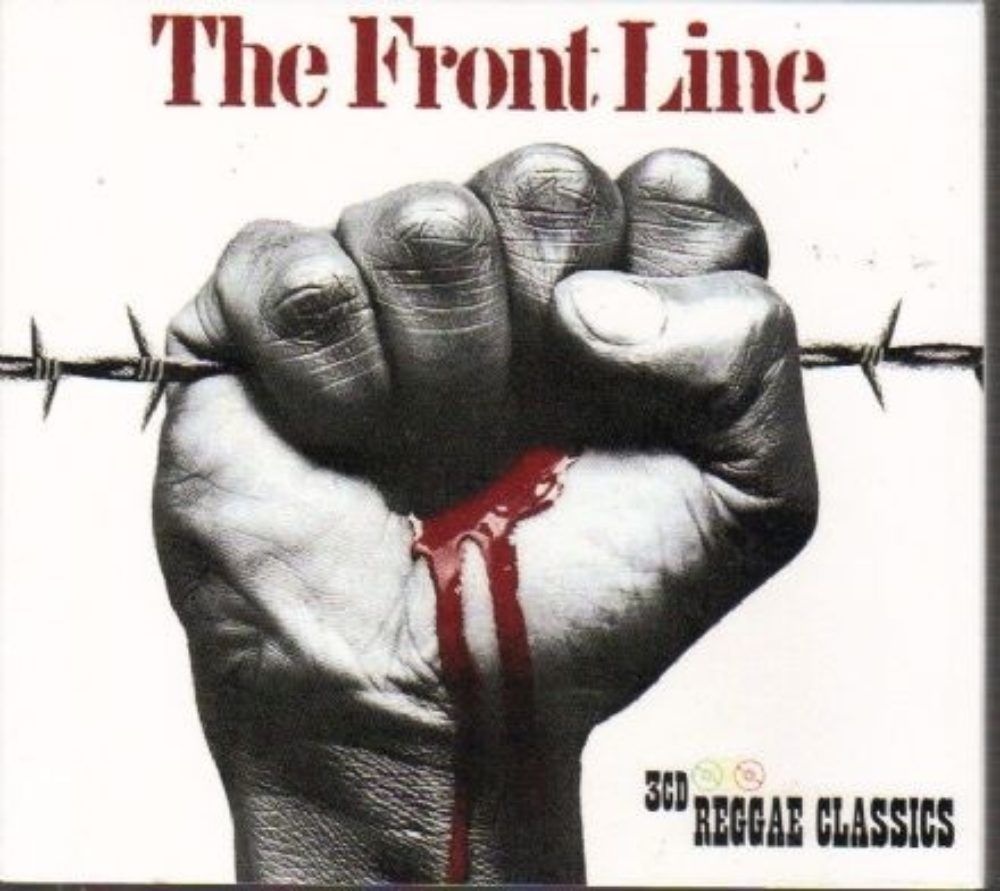

Shortly after arriving in London in 1971, Jumbo got a job at a Virgin Records store, and before long he was importing select foreign records to sell at all the company’s stores. A genial and enthusiastic promoter, he introduced innumerable customers to reggae and African pop. Within a few years he was on the staff of Virgin’s own record label, where his clients included such disparate artists as Mike Oldfield, Robert Wyatt, and the Sex Pistols. The opportunity to work with music that appealed much more to his interests and tastes came in 1978, when Virgin began Front Line, an imprint devoted to reggae, and put Jumbo in charge of Artists and Repertoire. This, however, put him in a tricky situation: having overstayed his British visa, he was fearful of being deported from the U.K., and with only a South African passport he would be denied entry into Jamaica. That worry was lifted when he became a British citizen in 1979. In just two years under his guidance, Front Line released more than 100 records by Jamaican acts such as I-Roy, U-Roy, the Mighty Diamonds, the Abyssinians, Culture, Gregory Isaacs and Big Youth.

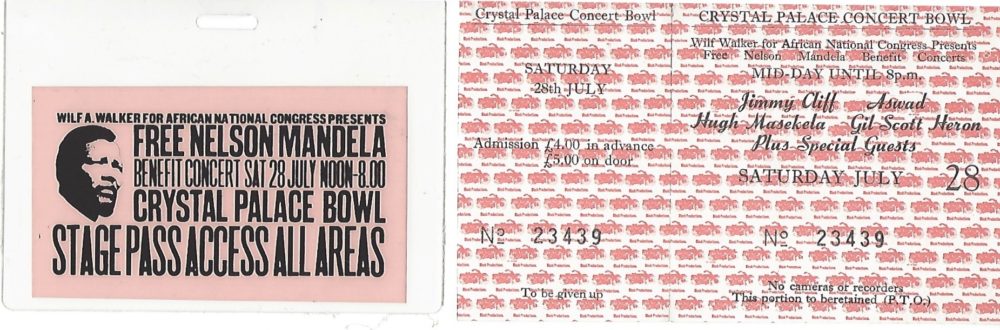

In the early 1980s Jumbo was a prominent figure in London’s cosmopolitan music culture. He presented concerts by South African émigrés such as Dudu Pukwana, Mongezi Feza and Julian Bahula, and by Thomas Mapfumo on his first visit from Zimbabwe. He introduced Kanda Bongo Man to Peter Gabriel, who booked him for the first World of Music and Dance (WOMAD) festival in ‘83, and when Fela Kuti ran into trouble in the U.K. that same year, Jumbo was called upon to resolve the problem. He established a weekly “Worldbeats” night at the club Dingwalls, where he spun selections from his massive record collection, mixing contemporary dance music from around the globe, developing a new broadly inclusive pop sensibility that disseminated far beyond that city and the British Isles. And he organized events in London to raise awareness of Nelson Mandela’s imprisonment and apply pressure on British businesses to divest from South African corporations complicit in apartheid. One such notable festival, "Free Nelson Mandela," was held July 28, 1984 at the Crystal Palace Concert Bowl.

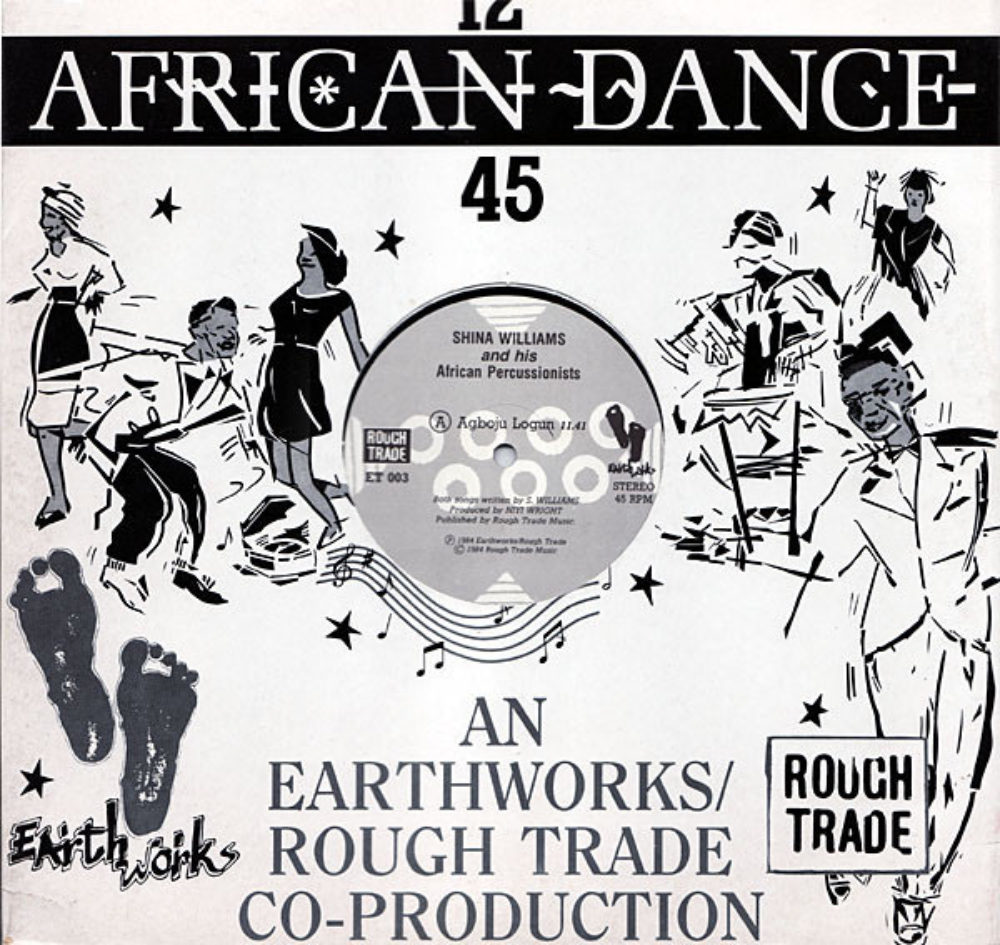

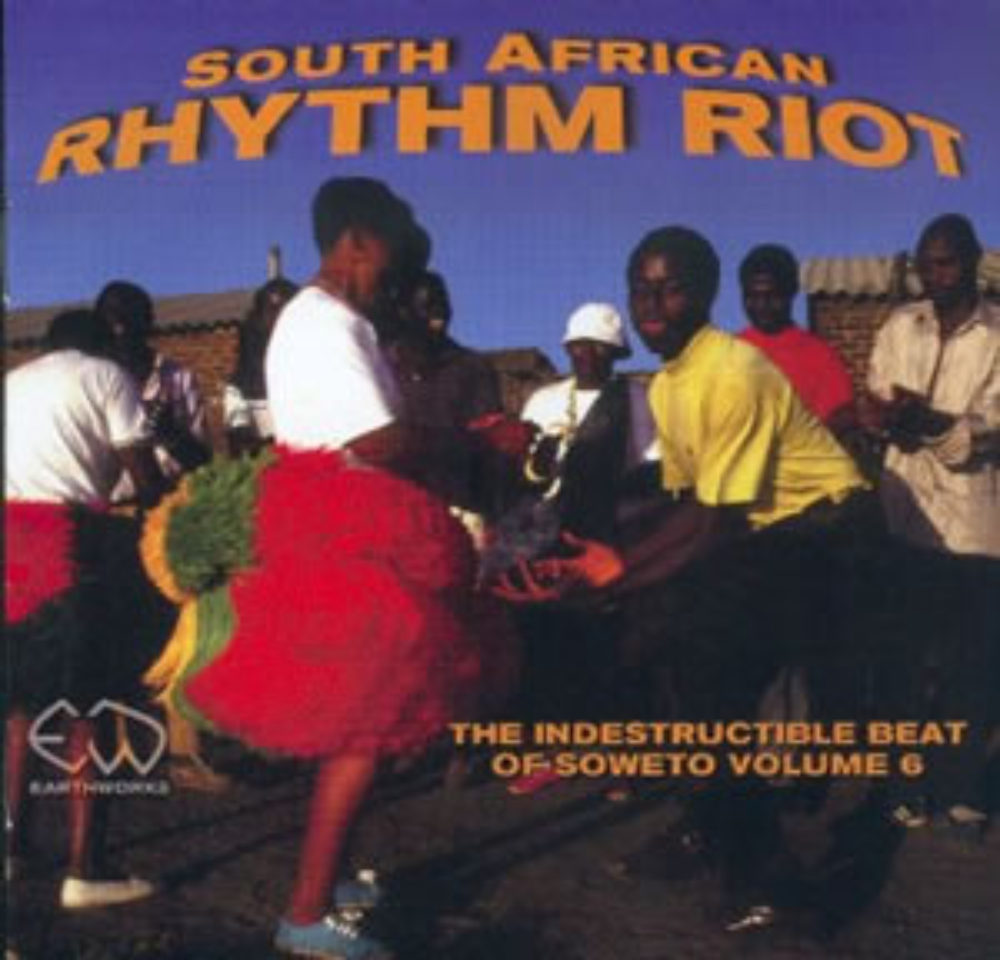

In 1983 Vanrenen left Virgin and launched his own record company, Earthworks. Its initial release was a single by Orchestra Jazira, an Anglo-Ghanaian band based in London, but it drew more attention for its first album, Viva! Zimbabwe, a compilation of songs by the Four Brothers, Thomas Mapfumo and the Blacks Unlimited, and other artists that few people outside of southeastern Africa had heard before. That same year Earthworks released Zulu Jive, an album compiled by Jumbo’s old friend from Cape Town, Trevor Herman, who followed that up with The Indestructible Beat of Soweto in ’85. These two albums gave a great many Europeans and North Americans their first exposure to Mahlathini, Joshua Sithole and Ladysmith Black Mambazo and initiated the global fascination with South African music that Paul Simon reiterated a year or more later with his Graceland. It was The Indestructible Beat of Soweto, though, that the influential American rock critic Robert Christgau deemed the most important album of the entire decade. And yet it was controversial. Anti-apartheid activists upbraided Vanrenen for contravening an international boycott of South African sports and culture. He countered that allowing the world to hear the power and glory of South African music actually advanced the cause of freedom and equality by undermining racist assumptions about superiority and inferiority. He persisted despite his disappointment at being denounced by natural allies.

Besides compilations of Cuban timba, Antillean zouk, Algerian rai and Congolese soukous, Earthworks released momentous albums by Thomas Mapfumo, Youssou N’dour, Samba Mapangala, Mahlathini and other African stars, and continued to make fans, but in 1987 Jumbo turned the business over to Trevor Herman in order to accept an invitation from Chris Blackwell to head Island Records’ Mango label. Over the next 11 years he worked closely with some of the brightest stars in world music, including Salif Keita, Baaba Maal and Angelique Kidjo. Jumbo was always more than a businessman. During one recording session, Kidjo went into labor and he assisted in delivering her baby in the studio. For two months he lived with Maal on the edge of the Sahara in northern Senegal, thriving on the heat and sere landscape.

When Blackwell left Island to form a new company, Palm Pictures, Vanrenen agreed to go with him. He was heavily involved in Palm Pictures’ trans-global multimedia project, One Giant Leap, but after its release he retired. Jumbo returned to South Africa in 2003 (post-apartheid) to care for his ailing mother. He kept up with local musicians, enjoyed deejaying at parties, and curated a YouTube channel called Wabangi Video. His cancer was diagnosed only three days before his death at age 69 in Cape Town on Nov, 18, 2018.

A giant in many aspects, Jumbo Vanrenen leaves a great legacy to the world and a gigantic void in it.

Thanks to Trevor Herman, Robert Urbanus and Banning Eyre. Photo by Atiyyah Khan.

Robert Leaver (AKA DJ BabaLoup) has curated a Spotify playlist of tracks that Jumbo had a hand in producing or distributing. View Robert's massive vinyl record collection on Discogs.

In addition, a tribute to Jumbo was broadcast recently on Worldwide FM, hosted by Paul Bradshaw (editor of Straight No Chaser magazine), with guests Trevor Herman and London DJ Dave Hucker. Click here to listen.