The continent of Africa contains millenniums of complex histories across hundreds and thousands of civilizations and cultures. The era of European colonization in Africa's history, which resulted in the borders of the 54 countries that we know of today, took place between the 1870s and 1990s, but the effects of this colonization continue to impact Africa in multiple, complicated ways. Independent Africa is a two-volume mixtape created by Boris Paillard, AKA DJ Mixanthrope, that consists of excerpts from songs and speeches by African musicians and political leaders discussing the state of their newly independent African nations.

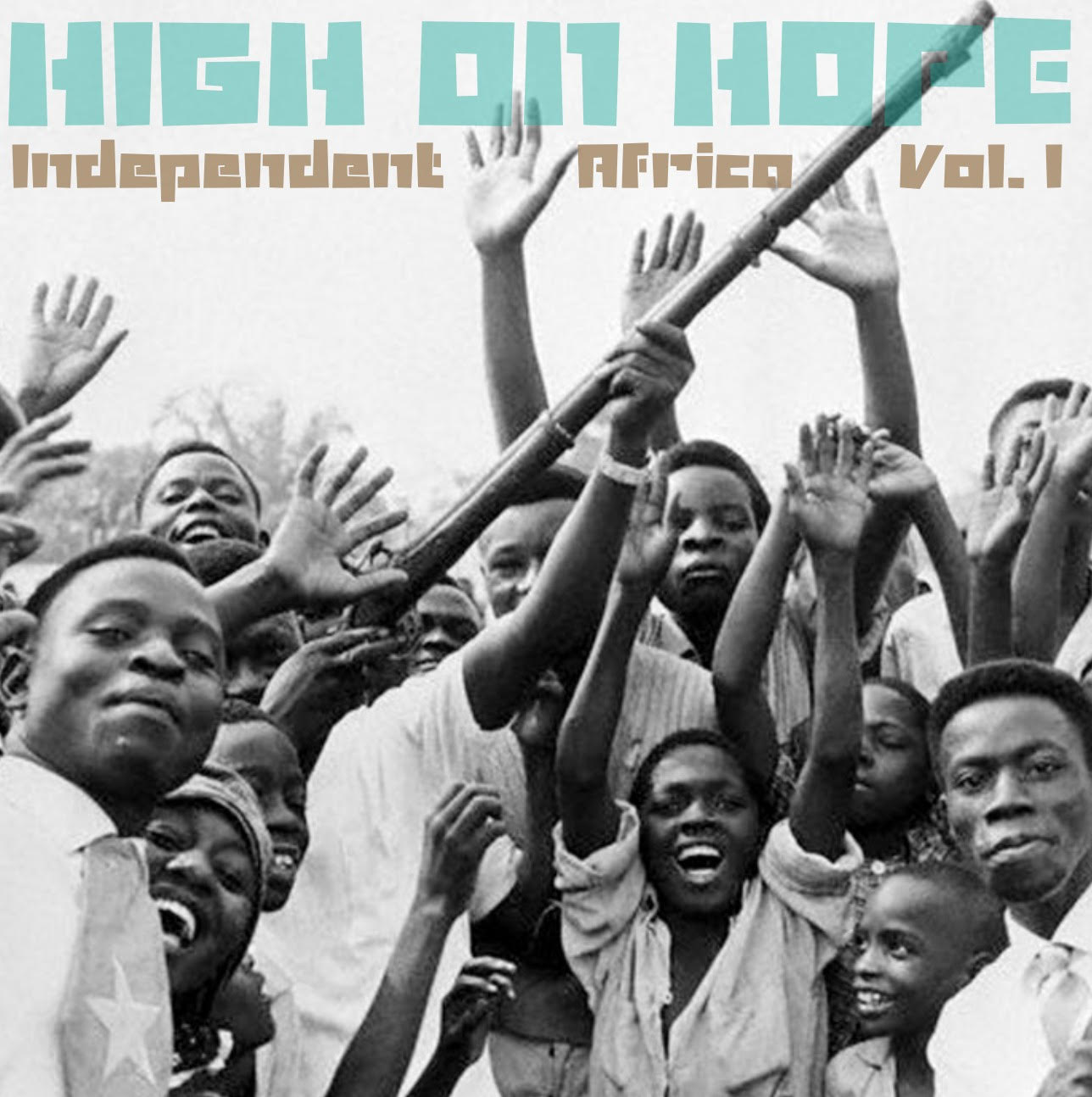

Vol. One: High On Hope

The themes expressed in Vol. One: High On Hope show the initial optimism among many African nations during and after decolonization.

The mixtape begins with these words from Ghana's first prime minister and president, Kwame Nkrumah in 1957 —"The black man is capable of managing his own affairs." Nkrumah declared Ghana fully independent from Britain on March 6, 1957, making Ghana the first African country to declare independence from European colonialism. One of the first songs on the mixtape, E.T. Mensah's "Ghana Freedom," celebrates independence and the tremendous leadership of Nkrumah. Ghana's independence sent shockwaves throughout Africa and the diaspora, inciting hope and excitement in other countries that knew they may become free soon as well. Even across the Atlantic this momentum can be felt in "Birth of Ghana" by the famous Trinidadian calypso singer Lord Kitchener, who sings "Ghana is the name we wish to proclaim. We will be jolly, merry, and gay the 6th of March, Independence Day!”

Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah

We now move to Guinea with a 1958 speech from Sekou Touré during the year he was elected to serve as the nation's first president following its independence from France—"Nous préférons la liberté que l’esclavage." (We prefer freedom to slavery). The same sense of triumph felt after Ghana's independence is heard in the track "Armée Guinéenne" (Guinean Army) by Bembeya Jazz National, one of Guinea's most important musical groups that saw much success during the early years of Guinean independence.

Sekou Touré

Sekou Touré

Next up is Gambia, represented by the Super Eagles and their song "Gambia, Zambia," that features grooving guitar and varied percussion with jubilant, harmonized vocals. The band was heavily influenced by the Beatles originally and were well known for playing Western-style pop music. Perhaps as a result of the nationalistic ethos after Gambia's independence in 1964, the Super Eagles changed their name to Ifang Bondi ("Be yourself" in Mandinka) in the early '70s while also switching gears musically by utilizing more traditional instruments and languages.

After more powerful words from Sekou Touré, we hear the beginning of Jackson Kaujeua's hit tune "The Wind of Change." After the Namibian artist's exile from South Africa as a result of his anti-apartheid activism in 1974, "The Wind of Change" gave Kaujeua great success after he moved to the U.K. to join the group Black Diamond with the help of his affiliates in the South West Africa People's Organization (SWAPO), the Namibian independence movement that now operates as the SWAPO Party of Namibia.

Jackson Kaujeua

After an interlude from Orchestra Baobab, an influential Afro-Cuban band from Senegal, Guinea-Bissau's anticolonial leader, Amilcar Cabral, declares, "Our fight is only against the Portuguese colonists, the foreign domination in our country" (1972). From this excerpt seeps in the Guinea-Bissau Creole vocals on the song "Guiné-Cabral" from Super Mama Djombo, a gumbe band named for the spirit Mama Djombo that fighters called on for protection during the War of Independence from Portugal between 1963 and 1974.

Suddenly we're in the sound world of Angolan Carlos Lamartine and his song "Ó Dipanda Wondo Tula Kiá." The music comes from Lamartine’s album Histórias da Casa Velha, which is made up of songs that “[highlight] the difficulties and victories of the liberation movements he was a part of during the years leading up to Angolan independence from Portugal in 1975."

Carlos Lamartine

Kwame Nkrumah returns with a vigorous reminder that “This mid-20th century is Africa’s. This decade is the decade of African independence! Forward then, to independence—to independence now!” With this assertion, we move forward into Congo-Kinshasa (present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo) as the soothing voice of Tabu Ley Rochereau, bandleader for Orchestre Afrisa International and one of Africa’s most influential singer/songwriters, proclaims "Viva la révolution" in the beginning of "Congo Nouveau, Afrique Nouvelle" (New Congo, New Africa) before a different recording of Jeannot Bombenga and Vox Africa seamlessly enters to finish the song.

Patrice Lumumba comes in to say, "Combattants de la liberté aujourd’hui victorieux," (Fighters of freedom are victorious today), after Lumumba's Mouvement National Congolais (MNC) party successfully overthrew the Belgian colonial forces in 1960 and made him the first democratically elected prime minister of Congo-Kinshasa. Lumumba's leadership and authority, like Nkrumah's, was incredibly inspiring to people in and outside of Congo-Kinshasa. The love that was felt for Lumumba and his independence movement is heard in songs like "Vive Patrice Lumumba" by the Congolese rumba group Vicky Longomba and African Jazz 1960, Depiano and Le Beguen Band's "Gouvernement Ya Congo," and one of the first pan-African hits, "Indépendance Cha Cha," by the highly popular and influential Congolese rumba band Le Grand Kallé et l'African Jazz, whose lyrics call for unity among different factions of the Congolese nationalist movement after independence in 1960.

Patrice Lumumba

After an excerpt from Charles De Gaulle's declaration of Algerian independence in 1962, we hear from the political Algerian musicians Slimane Azem and Mohamed Mazouni; Mazouni's song "Adieu la France, Bonjour l’Algérie" shares his excitement of returning to his home country, while Azem's song "Algérie mon beau" (Algeria my beautiful country) boasts of the wonders of Algeria despite the fact that he received death threats during the Algerian revolution and was forbidden from airing his music in the country.

Gabonese protest singer Pierre Akendengue switches us back into the West African sound world with his joyful "Afrika Obota" before Martinique-born poet Aimé Césaire discusses the literary movement that he helped found during the 1930s in France called négritude, which opposed French colonialism and advocated for a unified racial identity for Africans throughout the diaspora. Vol. One ends with another lively celebration of Kwame Nkrumah in Ebo Taylor and Bonze Konkoma's "Papa Kwame.”

Vol. Two: Freedom Hangovers

The songs and speeches featured in Vol. Two: Freedom Hangovers revolve around the feelings of "anger, frustration, and hope for change" in the face of "constant changing of power" as well as "corruption, neocolonialism, and neoslavery."

This volume starts of with words from people in Niger discussing how “The word independence sounds hollow.” Ivory Coast's Alpha Blondy then chimes in with his song "Journalistes en Danger" (Journalists in Danger), inspired by the assassination of Norbert Zongo, a journalist in Burkina Faso who ran a newspaper called L'Indépendant, which exposed corruption within Burkina Faso’s government. Alpha Blondy has a history of politically charged music with tracks like “Apartheid Is Nazism” (1985) and “Brigadier Sabari,” which documented his unlawful treatment by police in Abidjan, Ivory Coast.

Journalist Norbert Zongo

Next we hear from Senegalese rapper Didier Awadi. On his track "J’accuse," Awadi calls out France, the U.S., and other Western powers for their terrorism over and exploitation of nations in and outside of Africa, citing the Battle of Mogadishu, George Bush’s lies about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in addition to African coups sponsored by the French government and the assassination of Patrice Lumumba. Awadi goes on to call for accountability among African leaders and young Africans to resist these neocolonial forces.

Didier Awadi

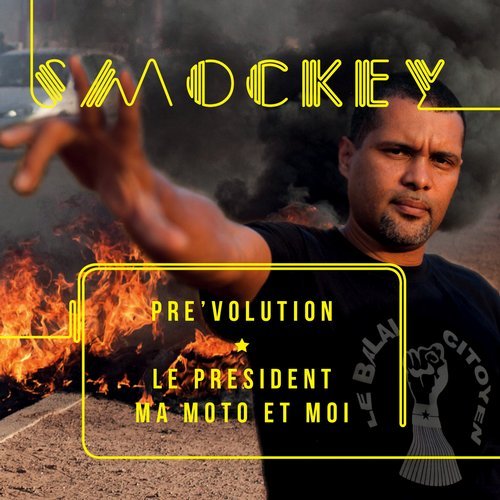

The first artist we hear from Burkina Faso is Smockey. The song "Combattants Oubliés" (Forgotten Fighters) features the late Burkinabe singer Amadou Balake and comes from Smockey's album Pre'volution: Le President, Ma Moto et Moi (My president, my bike and me), which includes songs that were written before and during the 2014 uprising in Burkina Faso which led to the end of Blaise Compaore's almost 27-year presidency. Smockey is a rapper and activist representing “Le Balai Citoyen," a youth movement in Burkina Faso that aims to “bring together artists, students and intellectuals to widely raise awareness and encourage political participation.”

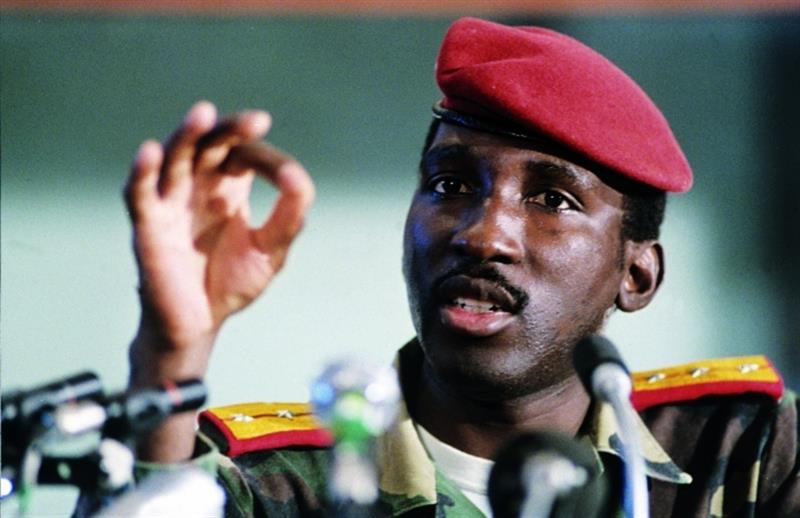

The French artist JP Manova pays tribute to the first president of Burkina Faso, Thomas Sankara, on the anniversary of his death on Oct. 15, 1987, in his song "Sankara." In 1983 Sankara led the coup that overthrew the French colonial government, allowing him to rename the country from Upper Volta to Burkina Faso. He served as president from 1983-87 and prioritized public health, women’s rights, and the reduction of famine, among many other ideals of his pan-African self-determinism. He was assassinated in 1987 during a coup led by the aforementioned Blaise Compaoré.

Another French artist we hear from is François Béranger, a musician of the French folk song tradition, in "Mamadou M’a Dit" (Mamadou told me). The twangy guitar, simple chord progressions, and catchy melody make the tune sound almost like a children’s song despite the subject matter of tragedies that occurred in Africa after colonizers left. “The colonists are gone. They put in their place a new elite, black, well-bleached. The white world laughs. The new ones are bizarre, are worse than the old ones. It is surely a coincidence. The white world laughs when a small sergeant becomes sacred emperor with a thousand ambitions. After all, it does not matter as long as land produces for whites what is necessary.” French singer/songwriter Michel Sardou also reflects on colonialism in his song, "Les Temps des Colonies" (The time of the colonies), which boasts of the good old days of shooting wild game and having servants within France's African colonies. Sardou received considerable backlash for the racism in his lyrics, though he says the song was clearly sarcastic.

Thomas Sankara

Thomas Sankara

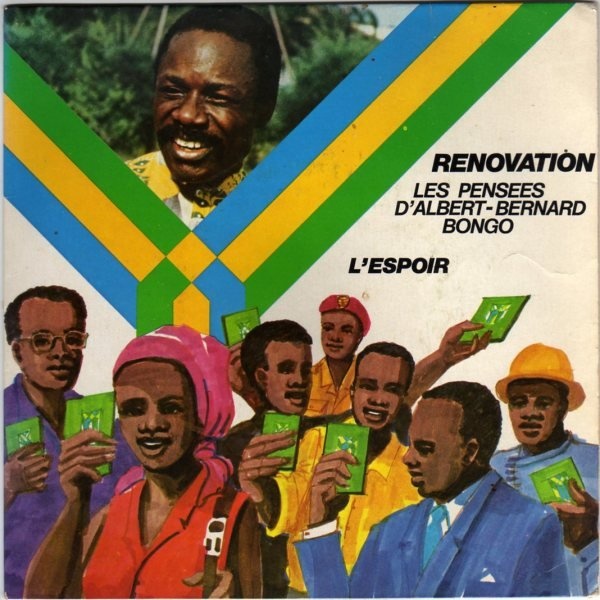

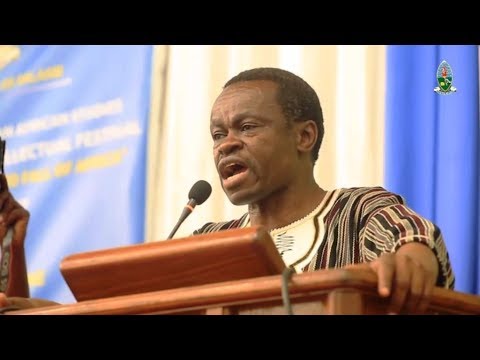

Vol. Two shows how music was used not only for protest but also propaganda. The revered Kenyan law professor and pan-Africanist Patrick Loch Otieno Lumumba (P.L.O. Lumumba) announces, "We are coauthors of our own misfortune...We elect hyenas to take care of goats, and when the goats are consumed we wonder why." One of these politicians was Omar Bongo, who became the second president of Gabon in 1967 and was heavily criticized for corruption throughout his 42-year presidency. Nonetheless, he continued to win re-election with the help of propaganda songs like Gérard La Viny's "Albert B. Bongo, le Président Qu’il Nous Faut" (Albert B. Bongo, the president we need), and Tchibanga's "Giscard Est l’Ami de Bongo," which celebrates the new relationship between the Gabonese and French governments with President Omar Bongo. Thankfully we get a glimpse of a new, perfect presidential candidate in the mock campaign offered by the well-known poet, singer and rhythm guitarist from Benin, G.G. Vikey, in "Président Vikey."

Propaganda poster for Omar Bongo

Propaganda poster for Omar Bongo

Musicians were not only used by governments for propaganda purposes, but also to build national and cultural pride. The first such group formed in Guinea was Balla et ses Balladins, who we hear on the track "Lumumba." The legacy of the former Congolese president is upheld also by many more artists in Vol. Two, like Franco Luambo Makiadi, one of the most important musical figures in Congo-Kinshasa for his effortlessly beautiful guitar playing and knowledge of rumba, which influenced the modern sound of Congolese music. We hear again from Angolan Carlos Lamartine on "Acorda Lumumba" from his album Histórias da Casa Velha, and Nigeria's legendary highlife musician E.C. Arinze too mourns Lumumba's death in "Lumumba Calypso," which details the revolutionary's incarceration, his escape from prison, and his eventual assassination. Another calypso tune that focuses on Congo-Kinshasa is "Congo War" by Lord Brynner. As a descendant of Congolese ancestors, the calypso and ska singer from Trinidad feels compelled to comment on the troubles that have ensued after the Belgians left the Congo, leaving leaders to fight over who gets “to be boss over the Congo.”

Patrick Loch Otieno Lumumba

After more powerful words from Kwame Nkrumah and Guinea-Bissau's Amilcar Cabral and more protest songs from the Baka people of Congo's rainforests, Gabon's Pierre Akendengue, and Ivorian zouglou group Les Salopards, we hear from Nelson Mandela in 1990—“We must not allow fear to stand in our way...I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have challenged the idea of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunity.” After Mandela's last word, Miriam Makeba joins in with "Ndodemnyama, Verwoerd!" ("Beware, Verwoerd!"), a song that protests against the former prime minister of South Africa from 1958 to 1966, Hendrik Verwoerd, who is referred to as the “architect of apartheid.” Mama Africa was an incredibly important figure during the struggle against apartheid for protesting against the system with her songs, and for spreading awareness of the condition of black South Africans with her Grammy award-winning album An Evening with Belafonte/Makeba, which she recorded with Harry Belafonte.

Miriam Makeba and Nelson Mandela

However, P.L.O. Lumumba warns of the dangers of resisting political regimes and corruption—“One of the most dangerous things in Africa today is to declare that you are going to fight against corruption even if you are the president. Corruption is such an enterprise that there will be no shortage of individuals that want to liquidate you and get rid of you all together, because corruption is a big industry. People pay school fees, people enjoy a good life on the basis of corruption. So those who have declared themselves to be on the forefront of corruption...must know that they are on the line of fire, and they can be eliminated at any time."

The end of Vol. Two shows that nonetheless, protest and resistance will always be found in music like "Stop Corruption (Gyae Corruption)" by prominent Ghanaian highlife musician Aaron Bebe Sukura and the Local Dimension Palm Wine Band. Franklin Boukaka from Congo-Brazzaville (present-day Republic of the Congo) summarizes the attitudes of many people throughout Africa post-colonization in the last two songs of the mixtape, "Le Bûcheron (Africa)" and "Les Immortels"--“Some for whom I voted went only for power and nice cars. When voting time is here I become someone for them. I wonder, the white man did leave Africa—whose independence did we achieve?”

Independent Africa, Vol. 3: The Fight Continues will be released during the fall of 2017 and will feature “contemporary songs of resistance against corrupt governments and social injustice.”

Starting this September, DJ Mixanthrope will also be curating a monthly event at Monarch in Berlin titled "African Beats & Pieces," featuring old and contemporary African music with DJs and special guests.

Independent Africa, Vol. 3: The Fight Continues will be released during the fall of 2017 and will feature “contemporary songs of resistance against corrupt governments and social injustice.”

Starting this September, DJ Mixanthrope will also be curating a monthly event at Monarch in Berlin titled "African Beats & Pieces," featuring old and contemporary African music with DJs and special guests.