Professor Brenda Berrian of the University of Pittsburgh first grooved to French Caribbean music while a graduate student doing research in France in the early 1970s, and hasn’t shaken the addiction since. In fact, she has become a foremost scholar of the music of the French Antilles, exploring its roots, social context, and lyrical messages in numerous academic publications, including her book Awakening Spaces: French Caribbean Popular Songs, Music and Culture (University of Chicago Press, 2000). Over the years, she has had the benefit of long personal interviews with many of the French Antilles’ great musicians, often in their homes in Guadeloupe, Martinique or France. Afropop Worldwide’s Siddhartha Mitter interviewed Berrian in late March 2009. This is part one of that interview. The following transcript was edited for length and clarity.

S.M: How did you first get interested in the music of the French Caribbean?

B.B: When I went to study in Paris in the 1970s to do my doctorate I befriended a lot of Martinicans and Guadeloupeans. I was constantly at their parties listening to Haitian music as well as their own music, and that was the first time I heard the music by Malavoi, while in Paris. But I didn’t actually go to the French Caribbean until 1976. My doctoral dissertation was about Négritude and Harlem Renaissance poetry and that explains my interest.

S.M: This was in the early seventies?

B.B: Yes it was; the early seventies. ‘72 to ‘74 was the exact time period that I was in Paris finishing up my work, where I befriended as I said Martinicans and Guadeloupeans, and went to their parties and listened to their music. I just enjoyed their rhythms and jumping up and dancing with them, not knowing that one day I was actually going to start writing about the music.

S.M: And you mentioned that they were listening mostly to Haitian music, at that time.

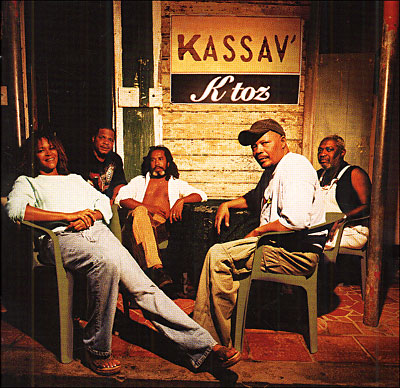

B.B: Most of it was Haitian music; yes, and that’s one of the reasons why Kassav’ developed in the late seventies in Guadeloupe; this was in opposition to Haitian music, which was dominating the French Caribbean at that time. You had Haitian music, you had salsa coming out of Cuba, you had the Ry-Co band from Congo Brazza... and you had members of Kassav’ playing for Ry-Co Band as well as for Manu Dibango. And I thought it was fascinating, these linkages as well as the opportunity to cross-play in different bands and to be exposed to African as well as Caribbean music. And the decision that since they’re a hybrid group of people, they’re from various countries, why not blend it all and make their own out of all this blending? And that fascinated me.

S.M: But you also got the opportunity to hear music from the French Antilles while in Paris.

B.B: They started taking me to these clubs where I heard the biguine being played by some of the pianists coming out of Guadeloupe and Martinique. And they said, “we do have our music, it’s mainly biguine, and jazzy, and we have Malavoi, trying to come up with its own sound with the violins” and I said, ‘but is that music really danceable?’ And they said, ‘listen carefully!’ But I’ve come to appreciate Malavoi. Because I was so accustomed to hearing that pulsating music coming out of Haiti, Malavoi was more restrained in my opinion. This was at the very beginning of their career in the early seventies when I heard that music.

At that time we were using albums and cassettes, particularly albums; they would put on albums, and one group I was exposed to was La Perfecta, which was way before Kassav’ came out. So not only was I listening to Malavoi, which was the violins with the biguine music, but you had La Perfecta, which was sort of using a lot of the Dominican cadence music, they were extremely popular in Martinique.

So I left France and moved to Gabon in Central Africa where I also was hearing albums because I worked with Martinicans and Guadeloupeans at the Université Nationale du Gabon, and they were bringing in their music. They were constantly flying back and forth to Martinique and Guadeloupe during the summer holidays and they were returning with the most recent music that was released and heard in their respective islands, if you were going through Paris you would hear what that music was. Now at the time there wasn’t a lot of exposure to the music on the radio stations as you hear today in Paris, so times have evolved in their favor in terms of exposing people to the music.

S.M: Were there records being actually made on the islands themselves at that time?

B.B: Knowing the situation between France’s overseas territories, France dominates, so you really have to come to Paris to have your albums pressed and distributed. There were a few recording studios in Guadeloupe and Martinique, particularly Henri Debs in Guadeloupe, he was very influential; but early on you had to be in France and produce your records in France, until the late ‘70s onwards when they started opening up their own studios on the two islands.

S.M: What are some of the oldest recordings that one can find?

B.B: They have some old recordings thanks to Sole Kali, who’s in Martinique, he’s been trying to find the old albums and to record them on a CD, so you can go back and hear some Alexandre Stellio, the pianist, biguine music, you can hear Coppet, you can hear Benoit, you can hear some old Leona Gabriel who dominated music for over thirty years through her radio show in Martinique; some Manuel Lapioche from Guadeloupe, you have Moune de Revel who lives in Paris whose recordings you can find to. So there’s this conscious attempt to try to record; where you have the old sound, you can hear the original sounds of the music and the singing style of that music that started in the 1920’s and 30’s in Paris, because they were primarily based in Paris singing and playing at that time, in the little clubs for tourists and for the French population.

S.M: So even back then musicians were migrating to the metropole?

B.B: Exactly. Back in Guadeloupe and Martinique, the musicians were full time workers, and they worked as musicians part time. That explains why they had to migrate to the metropole as well, because they could not be professional musicians living in their little island. The population simply could not sustain them. So that explains this constant movement into France whether they wanted to do it or not; if they wanted to be exposed, if they wanted to be professionals, they’d think ‘I have to go to the metropole whether I want to or not, if I want to be a professional musician, and earn money from my music. Otherwise I must work a full time job and just play music part time, and always have to get permission from my employer to release me so I can tour with my band off the islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe.’ And that created quite a problem, especially for the Malavoi musicians, because all of them were employed full time and had to get release time from their employers to travel around.

Even to do your studies you had to go to the metropole after the lycée, after high school, until they formed the Université des Antilles, and if you want to do even higher studies, or you need to do special internships even now, you have to go to France and then return to your island after. So it creates a lot of hardship, whether you’re a musician or an engineer or teacher or no matter what field you’re in, you have to constantly go to the metropole to perfect your skills.

S.M: So that created a significant European influence for a lot of the music. But there was a traditional music as well, right?

B.B: Right. You have this dichotomy, where you have the urban music, which is what I was speaking about, the biguine, the mazurka, the quadrille, the jazz music and then when you went into the rural areas you heard the drumming music, the bélé in Martinique, the gwo ka in Guadeloupe. And it was along class lines, color lines as well, dictating who was exposed to what. And that created a lot of tension across the islands as well. Because it was also associated with French language or Creole language, they had to decide ‘do we use Creole or mix Creole and French when we sing our songs,’ and that created a lot of tension as well.

The Caribbean people who worked in the habitations, which was the term for the sugar plantations, they were exposed to European music and had to learn to play those instruments on those plantations. So you see how it evolved, where you’re exposed to the music coming from Europe, you’re told you have to play that music to entertain the békés, that’s what you called them in Martinique, or the blancs-pays, that’s what you called them in Guadeloupe, you had to play the music that they like. And then you start putting your own overlay of feelings into this music as well. So that’s what eventually became known as the urban music. Whereas hidden back in the hills, as they call it mornes, you had the people who were primarily, you would say, field slaves, who would continually play the drum which had been banned. You know there were two instruments that had been banned under colonization; you were not supposed to play the drum or the banjo during colonization, because of the fear of passing along messages to rebellion to spread across the islands, to bring about the downfall of slavery in the 19th century.

S.M: The drums... but also the banjo? That’s surprising.

B.B: I know, when I heard about it I said ‘what was the problem with the banjo?’ And they said ‘you could actually beat something out on the banjo as well, so you were not to play it.’ And so when you have the middle class beginning to appear, meaning mainly mulatto people in Martinique and Guadeloupe, there were parents heavily influenced by the French educational system and they wanted their kids to become, you know, Black French people, and they would say you cannot play the banjo. ‘You can play the violin, but not that horrible banjo, which is very vulgar.’ So on class lines the banjo became known for the rural people or the low income people throughout the Caribbean, and that’s why Kali, who is a very popular Martinican Rastafarian musician right now coming from a middle class family, deliberately chose that banjo and to play it in his music when he started performing back in the 1980s.

S.M: So what are the key differences we need to understand between the situation in Martinique and the situation in Guadeloupe?

B.B: You have more Indians from India in Guadeloupe than you do in Martinique. You have a whole section in Guadeloupe where you see descendents of the indentured Indians who came to work on the sugarcane plantations in Guadeloupe. Martinique is more mixed, in fact Martinique is considered to be more mulatto looking than Guadeloupe. You have a larger percentage of bekes and they’re very influential, these are the descendants of the French plantation owners who control the economy in both Martinique and Guadeloupe, and in Martinique there tends to be more interest in jazz fusion music than there is in Guadeloupe. In Guadeloupe there is more interest in African and reggae music, although there is interest in reggae in Martinique. When you enter Guadeloupe and you listen to the music, you’re going to hear a lot of reggae, a lot of African music being played, as opposed to Martinique, where you hear more French music, more African American music, more jazz.

And in Guadeloupe you’re going to hear a lot of drumming. The gwo ka is easier to play than the bélé from Martinique, in fact a lot of Martinicans can play the gwo ka as opposed to the bélé, because it’s so difficult to play, from what they’ve told me. Guadeloupe is considered to be more roots oriented, more Afrocentric, than Martinique, although Martinique is really beginning to shift now. There’s a shift going on in Martinique, but Guadeloupe has always been known for being more vocal, more political, more open about their uneasiness about their relationship with France than Martinique.

Another thing when I was in Guadeloupe, I found that the Guadeloupeans always complained about the Martinicans. Whereas in Martinique they really didn’t have much to say. They’re always talking about “la mère patrie” meaning France. Whereas in Guadeloupe it was “l’Afrique! Les Etats Unis!” The Martinicans were more open towards me, more willing to talk to me about their musical productions. I had a terrible time in Guadeloupe. I had to finally enlist the aid of Freddy Marshall, a well known music producer, to open the doors for me in Guadeloupe. He said Guadeloupeans have been so hurt and so betrayed by foreigners that they were very hesitant to talk to foreigners about their craft. As opposed to Martinique where I just called their numbers and said “I was given your number,” and they said, “oh, ok, no problem.”

S.M: What were you trying to find out in Guadeloupe?

B.B: Well I wanted to get an understanding of the gwo ka music since it’s very strong in Guadeloupe. Especially if you listen to the old recordings of bands like Akiyo, and Cafe Mbelo, very famous gwo ka players, this music is very interesting and I wanted to take some lessons to figure out what some of these rhythms are, which I was able to do while I was in Guadeloupe. And I wanted to figure out why there was this keener interest in African music as opposed to Martinique, and of course Kassav’! Since it started with Guadeloupeans in Guadeloupe, and as I said in my book, in 1986 I was walking down the streets of Pointe a Pitre and I head this, what I thought was soukous music, and I thought ‘oh my goodness!’ because it reminded me of my childhood in the Congo. So I ran into this record store and said “oh please, what is it you’re playing, please give me! What band is that from the Congo?” And they said, “That band is our band, it’s Kassav’!” And I said “well I’ll be!” And it turned out Kassav’ had been in the Congo, and that’s why they were playing this song that I heard, “Sye Bwa.” And when I interviewed them later on they said yes we have been in the Congo and we wanted to fuse some of the Congolese music in our songs to express our appreciation to the Congolese public for buying our records and enjoying our music. So it all comes full circle.

S.M: But this drum-oriented music took some time to emerge in polite society...

B.B: Well it’s what they call their traditional music, which is performed at night, particularly during carnaval time. That’s the foundation of carnaval music, the gwo ka, the drumming, in Guadeloupe and the bélé in Martinique. There are different rhythms and dance that you perform, starting on the plantations you have the love dances, the battle dances, the harvest dances and that’s across both islands.

In Guadeloupe back in the 70s they had a drummer named Velo who used to sit in the town square and play his drums. Everyone thought he was crazy, but now it’s quite common, you’re going to hear people playing the drums on the streets, but at that time in the 70’s they were just appalled, ‘how could someone be doing this?’ But he was bringing their attention to the drum and the foundation of their music. It linked to their history as well, in terms of slavery; because slavery was something that was not taught in the school system, they followed the French school system, it was something that you talked about in lowered voices, didn’t openly admit it, and so drumming was associated with slavery. And that was something that you did in the dark, back in the woods, back in the mountains, and not in the city streets. So what I love that is happening in Guadeloupe and Martinique is that drumming is now being seen in urban settings and openly being played on stages, in concert halls and night clubs whereas before it was played back in the woods.

But now you’re going to hear it in both urban and rural settings because consciousness has been raised. It really helped when the new law was passed in 2001, the Taubira law in France, where the French government formally announced in the National assembly that slavery was a crime against humanity and you have to start teaching now about slavery in the school system. That has helped raise this interest in the gwo ka and the bélé. You can now play it and fuse it with zouk or any other music that you want to play.

S.M: But before we get to all this, the story really begins in the late 60’s with Malavoi. Tell us how that group came about.

B.B: Well the founder of Malavoi happened to be the nephew of Aimé Cesaire, named Emmanuel “Mano” Cesaire. He is a teacher in a high school in this town of Robert in Malavoi, but at the time he had grown up in a very lively section of Fort de France, where barbershops, and beauty parlors consisted of people who liked to sing and dance, so if you went to get your hair cut or curled you would be seeing musicians, even the person who cut your hair would be singing. It was very, very lively.

Mano Cesaire was exposed to this music since he was from the middle class, he had a very famous uncle who became a member of the French assembly and the mayor of Fort-de-France for over 30 years, and so he was told to study the violin. His classmate Jean Paul Soime, whose aunt was Leona Gabriel, the biguine singer who I mentioned earlier, who sang in the 1920s and recorded until her death in the 60’s, he studied violin as well. Some other members; they were going to the Lycee Schoelcher, playing salsa, because they were listening to music coming from Cuba.

And they said ‘we need to start thinking about our music. What is so popular with our music, especially with our parents’ generation and our generation, is that it was the biguine.’ So they started to blend a little salsa, with some biguine. Then they were listening to American music and thought ‘let’s put a little American music in there,’ and they formed the Merry Lads. And the Merry Lads is what they were originally called, when they were running around playing at different fairs.

S.M: What was the name in French?

B.B: No, they used the English term the Merry Lads, because it was very popular at that time to show that you know a little English, and to show that you were cosmopolitan you gave yourself an English name. So that was their name, The Merry Lads, in English. They changed the name to Malavoi when they were asked to start to perform and earn some money performing, and they said ‘what should we choose?’

They thought about this unique sugar cane that exists on the island Martinique, and so they said we’ll call ourselves Malavoi, and become synonymous with our land, because we’re proud of our land and we’re proud of being Martinicans, and we want to talk about how we die and we nourish the earth and become part of the next generation, and we live close to the land with our flowers and our plants. Because where can you go in Guadeloupe and Martinique without people having their flowers and plants everywhere? Eating outside a lot on the veranda, you’re in constant touch with nature.

And so that’s one of the reasons for choosing the term Malavoi and beginning to sing songs about the whole process of being in exile, since so many of them went abroad to study and then came back to Martinique. They talked about vegetation; a lot of the songs are about rain, about flowers, about the ocean, about boats, since that is part of living on the island. And to talk about their childhood, particularly their childhood and how they were exposed to living in two worlds, you know about the Creole world back in your own neighborhood, but once you entered the school you were only exposed to what the French students were studying in France, even though you were there in Martinique. So they talked about that a lot in their music as well.

Most of the members of Malavoi determined that they were going to make their homes in Martinique. They were not going to live in France. They went to France for schooling, for their training, but when it came time to start their families and to work, they wanted to live in Martinique. So that meant they had to work jobs as teachers or fonctionnaires [civil servants], they had full time jobs and they could only perform part time as musicians even though they were very well trained as musicians. They could read music, composed their own music, but they did not want to become full time professionals if it meant that they had to live in France. That was the difference between them and Kassav’, because the Kassav’ musicians decided that if they were going to earn their living entirely from their concerts and royalties from their albums, then that meant they had to relocate and move to France, as opposed to Malavoi.

S.M: What do you think made the Malavoi musicians decide to live in Martinique?

B.B: I think it had a lot to do with the generation of that time, in the 60’s and the 70’s, so you were talking about the height of the civil rights movement in the US; this is when they started having some disturbances in Martinique and Guadeloupe, talking about independence from France, you had riots in the streets, people protesting and strikes. There was more of a rise in consciousness about ‘what does it mean to be black and to be a Caribbean person.’ And there was awareness of what was going on in the United States and the independence of the African nations, and so many of them had family members who were working in Africa, they made a conscious decision: We are Martiniquans first, we happen to have French nationality, but we are Martiniquans, we are proud of it, and we are going to stay here. And we want our families to be raised in Martinique, not in France. Because most of them said they did not enjoy their experience in France very much. They found it hostile, cold and damp, and they just wanted to get there and get out and come back to Martinique.

S.M: But they had to go to France to record?

B.B: Yes they did. But then a recording studio Declic opened up in Martinique, so they had recorded with Debs and with Declic and some recording studios where you could actually do the recording in the islands, but the actual pressing of the albums or the CDs were always done from Paris. And the marketing and distribution were done from Paris. Everything had to be sent to Paris, even though you recorded locally.

S.M: So what are the key phases in their work?

B.B: They really began becoming popular in the 1970’s, and they’ve gone through four formations, four different times when they’ve quit and re-started. They really became popular in the late 80’s under Paulo Rosine, the pianist. He really pushed that group, he made them perform six nights a week at local clubs or local dances in Martinique. And he was the one who was responsible for getting them tours all over the world. But he died in his early forties, in 1993, of cancer. And Malavoi has never really recovered since his death. They have tried but they have never reached that state of excitement; they haven’t sold records like they did in the latter part of the 80s and the early 90s under Paulo Rosine.

Paulo Rosine was tough. And they talk about how he pushed them, how he was aggressive, but when you met Mano, he’s a very gentle person. So was Soime, who was one of the founding members and who grew up with Mano Cesaire but he died two years ago as well. He was too gentle and very spiritual, tended to his bonsai plants. But Paulo Rosine was definitely a task master.

S.M: You’ve studied their lyrics in detail. What are some of their most interesting songs and themes?

B.B: Starting in 1968 at Lycee Schoelcher, Mano Cesaire was the one who was writing a lot of the songs and he was the founding member as well. And they would sing songs about Albé, which is Creole for Albert, they would sing about Albert and how laid back a person he was. Or they would sing a song called “En les mon la,” “on the hill,” which is looking at my land, I’m standing on the hill and looking at my land, and the beauty of Martinique, its flowers, its vegetation. Those were the kind of songs they would sing.

Once they began to play even more and change their name to Malavoi, which was in the 1970s, they began to sing more serious songs, and that’s why I mention the song “La Case à Lucie.” On one level it just means “Lucy’s Place;” it’s about a fellow who lies to drink his punch, his tea punch, yet at 12 noon you see him with a hangover near the school near Lucy’s place, and you say uh oh, he’s teetering on alcoholism. But one nice thing about Creole songs is that they have two layers. Superficially that’s what the song is saying, so people dance to it, they say ‘oh yes, he really loves his rum, he likes to have a good time.’ But underneath it the message was saying, ‘here we are Martinique, in a stupor. We’re teetering on alcoholism because we are so dependent upon France that’s directing us and pulling the strings in terms of the economic cultural and social situation here.’

So that’s what is so interesting about Creole music: It always has another level underneath it. So you might think the song is very light hearted but underneath when you pay close attention there’s always a very serious message under the songs. So the songs began to be about that; they wrote about exile, what is it to be an exile, meaning you had to go to France to work and to study, and how you hated the cold and the dampness and people didn’t see you as a citizen, they said ‘you’re Black;’ and you say ‘I’m a citizen! I carry a French passport!’ But the French in the metropole said ‘no you’re not.’

They sang about gossiping because you’re on an island, what else do you have to do but to gossip? So they made songs about gossip. One that’s real popular is called “Sport National.” They sing songs about the rain, in the Caribbean you have the rainy season, called “Après la pli.” Songs about Tintinbel, which is a woman who’s a capresse, which in the French Caribbean means half-black half -Indian, and how beautiful she is, and how this man’s heart is just pumping as he’s looking at this gorgeous beautiful woman. They sing songs about childhood, children across cultural differences, especially if one is mulatto and one is not, coming from rural area and urban areas, and how they can go across these differences and really appreciate the internal parts of themselves.

And Rosine who had been an avid gardener wrote a beautiful song called “Jou ouvé” which means “daybreak.” And he talks about what it’s like to wake up in the morning at 6 o’clock and see the dew on the leaves and hear the bells -- since they were all Catholic you hear the bells at 6 o’clock calling the people to mass -- and you hear the birds chirping, the rooster crowing. And they sing songs about the pleasure of being rooted in your own land, and thinking about the people who had come before you, the slaves who had helped to till this land. They’re songs like that, very interesting songs, but a lot about their childhood, about nostalgia, and about the beauty of Martinique, because it is one of the most beautiful places you’re ever going to see.

S.M: What was the layered message, the double message in “Jou ouvé?”

B.B: The daybreak? Well in other words he’s talking about gardening, smelling the flowers, but at the same time he is talking about a visual identification with his island. He is talking about how daytime is the time to give respect to your home and to put your body into action. In other words, here we are, day is breaking, let’s not be the laid-back people that people hear about, because people always think Caribbean people are lazy and take their time. He’s saying no, we have to move our bodies. We have to respect our home and become more active in terms of our future and how we’re going to live our lives. That was another message in “Jou ouvé.”

When he died of cancer in 1993, the funeral was held in February 1993, and leaving the cathedral, Malavoi came outside and played “Jou ouvé” as they were bringing the casket out. It was the most moving thing to see, it brought tears to your eyes. And everyone who was at the cathedral, including Aimé Cesaire, broke out singing “Jou ouvé,” you just saw this enormous crowd singing as Malavoi was playing with the violins, the instruments, singing “we’re taking him home now. He’s opened the day for us, his death is bringing us even a much brighter future.” So it’s a very tender song but a very positive song as well with lots of hope in it.

S.M: Do you think Malavoi staying in Martinique was also affected by the ideas of négritude?

B.B: I think so. Remember, Mano Cesaire’s uncle was Aime Cesaire, the father of négritude, so Mano had to know about négritude. With Mano growing up in this family he was very aware of politics and the importance of proclaiming one’s blackness and affirming one’s roots thanks to the influence of his uncle Aime Cesaire, and his aunt who died quite young, Suzanne Cesaire, who herself was a writer in the Négritude movement. So I think the reading of the poetry – which they were not taught in the school system by the way – but he and his friends were reading the poetry by his uncle Aime Cesaire, reading the plays Aime Cesaire wrote about King Christophe of Haiti, and other poems that were being produced across Africa and the Caribbean, so I think that had a lot to do with them deciding to stay in Martinique. They thought ‘let’s not run to the metropole, and we can still be musicians, even if we’re not full time musicians.’ That I think was a conscious decision.

S.M: But they expressed their politics in a very low-key way.

B.B: Very subtle. Whereas Kassav’ was more militant. But what was very interesting was the public, since they were caught up in the rhythm of the zouk songs, they always said that the Kassav’ songs were very light-weight, and that’s one of the reasons for me wanting to look at their music, thinking, I don’t think so, you are mistaken. And when I sat down to look at their songs and talk to Jocelyne Béroard and other members of Kassav’, I said, ‘oh my goodness, these songs are very, very political. And the population is not aware of it.’ Although they are now more aware of how political Kassav’ songs are. But the early criticism was it was all just light-weight zouk, just jumping up and down, just dancing. And that was not the truth, because there’s always a different layer to those songs.