On this week’s episode of Afropop Worldwide, we explore the music of the Brazilian Amazon region. Darien Lamen teaches at the University of Wisconsin-Madison as a post-doctoral fellow in Spanish and Portuguese. Outside Brazil, he is probably the foremost expert on lambada and guitarrada—genres of music that come from the Amazonian state of Pará. Recently, there’s been a resurgence of interest in the area's popular music, both in Pará and around Brazil. We asked Darien to tell us the whole story from the beginning. Here, you can find the full transcript of our interview, which is featured in the Hip Deep episode The Mighty Amazon.

Marlon Bishop: So to start off—how did you become interested in music from the Amazon region?

Darien Lamen: What I think captured my interest the most was seeing such a strong presence of Latin American and circum-Caribbean music in Belém. Brazil’s a country where, before the 1960s, this kind of music had a very strong presence, thanks to the Mexican and Cuban music industries’ influence in the hemisphere.

Belém, in some ways, preserved that connection with the rest of Latin America and contributed something back to it, whereas the rest of Brazil turned away from those kinds of traditions— bolero, rumba, mambo, merengue. Belém had a sub-culture that was really nourished by a constant stream of new music coming across the border from the neighboring Guyanas—from French Guiana, from Suriname—that included merengues and cumbias and cadence-lypso music that was never released in Brazil.

Let’s set the scene—where and what is Belém?

Belém is a large metropolis of 1.5 million people located in the eastern Amazon. It’s the capital of the state of Pará. Its position as a port city in the lower Amazon basin has given it a unique relationship to the circum-Caribbean and also the rest of Brazil.

There’s a saying that Belém grew up with its back to Brazil, which isn’t totally accurate, but it does point to the way that Belém has been turned outwards towards the Caribbean during several moments in the 20th century.

Belém was founded as a Portuguese outpost to control access to the interior of the Amazon where colonial powers were vying for access to precious metals, woods and so on. In the 1830s there was a period of insurrection after Brazil gained its independence from Portugal where various interests near Belém didn’t want to recognize the distant authority of the new Brazilian emperor. So, the region has a history of being a divergent Brazil in this sense.

What does it feel like to be there? What kind of activity goes on in the city? Give us a sense.

Belém is a very, very vibrant—chaotic, even—city, and it’s a really exciting place to be.

It’s surrounded on three sides by water, at the confluence of a number of different rivers that are heading out to the Atlantic some 60 miles downstream. The city is a major port of call for large freighters that are passing through the region either on their way to southern Brazil or out to the Caribbean.

It’s an important way-station for mineral ore that's passing from the interior of the Amazon out to the rest of the world. You also see a lot of small fishing and cargo boats that bring loads of açaí and other agricultural goods to market from around the interior.

So how is it that Caribbean music, rather than what we traditionally think of as “Brazilian music, ” took off in Belém?

The story is often told the following way: That short-wave radio was used to pick up Caribbean frequencies because radio broadcasts from the south of Brazil arrived with bad reception.

I think that's part of the story. I think an important piece of the puzzle is the sound-system institution, which begins in the 1950s and ‘60s with people simply hooking up turntables to loud speakers. These sound systems began to proliferate in Belém’s residential neighborhoods, and one way they found to compete with one another was to spin exclusive records, the harder to come by, the better.

A lot of the albums that sound systems played were being brought by contrabandists to Belém. They had never been released in Brazil before, so the sound systems would use these albums to do what they call fazer farol—to shine a spotlight or a beacon that would attract audiences.

You mentioned the contrabandists. Who were they and how were they involved in popularizing Caribbean music?

There was a vibrant illicit trade with, say, French Guiana, which was connected to the markets of Europe, in precious stones and in animal hides and things of this nature. A lot of the people who crossed that border regularly would bring back things like perfumes, whiskey—the symbols of modernity at the time.

Among those things were records. As far as I can tell, the authorities never criminalized people for bringing back records particularly but because they came in the flux of the rest of the contraband, they had kind of a mystique, an air of subversiveness around them.

Subversiveness, how?

Well, the contrabandist became kind of a folk hero figure of the periphery of Belém during the ‘60s and ‘70s. It was someone who knew how to navigate the ins and outs of the port system, of the Amazonian river system, and who brought the steady stream of music from abroad that animated these sound system parties.

And at some point, this Caribbean music becomes known locally as lambada, right? How did that happen?

The story is that two radio personalities, Haroldo Caraciolo and Paulo Ronaldo, were the first to jokingly popularize the name lambada, which was a rural colloquialism for a “lashing.”

They would introduce a song like the merengue or any fast-paced song by saying, “Here comes a lambada, or here’s a lambada on your backs,” which really means something like, “Here’s a whopper. Here’s a lashing. Or here’s a hot rhythm, basically, to dance to.”

It’s any rhythm—it can be Caribbean or Brazilian—that is uptempo, made for dancing and maybe has somewhat of a sensual aspect to it.

What kind of environments did people listen to lambada in?

People danced a lot of lambada at the dance halls catering to migrants who were coming, working as stevedores unloading the boats in Belém’s ports, maybe looking for some income for the season before going back to the rural areas.

And, on the weekends or at the end of the day, they might have a little bit of extra cash in their pockets, and they would go to spend this money in the gafieiras, the dance halls located on the urban peripheries.

Gafieira became a synonym for “brothel” during this period. Often, there was prostitution associated with these spaces, but there was a broader social stigma that attached itself both to lower-class places of leisure and to hot Caribbean music.

And here’s the real question: Why do you think that Caribbean music became popular in Belém, other than the fact that it was available to listen to?

In part, the sound of the lambada, of the merengue, of these things, was something that signified a world beyond the local, that signified a certain kind of subversive, contraband mobility, that signified a certain kind of cosmopolitan, hemispheric circulation of goods, the signs of leisure status. I think that in this general context, these types of music became very, very popular.

And at what point do local bands start playing and adapting these Caribbean sounds themselves?

The dance bands that existed around Belém always had a mandate to play pretty much everything within the general soundscape of the city. They began to hear a lot of this Caribbean music in the sound systems and on AM radio, and adapted it for their dance bands straight away.

In the case of Mestre Vieira, who is from the rural town of Barcarena, about an hour and a half boat ride from Belém—his dance band was kind of typical for the 1970s. It had a horn section, banjo and percussion.

He began to incorporate the electric guitar into the ensemble in the 1970s, which he then used to translate a lot of these horn gestures that you might associate with the mambo—these horn hits—or to translate the sinuous saxophone line of a merengue solo.

Tell us a little more about the biography of Mestre Vieira.

Joaquim Vieira was born in 1934, he says in a canoe somewhere near Barcarena. His father was Portuguese, who came to Brazil in his 40s to work with lumber, and his mother was a paraense, a local.

Vieira always had a kind of tortured relationship with his father, who didn’t approve of him playing music. Vieira was very intrigued by music he heard in Belém, and as a youth he said he’d often row the full six or seven hours there from his hometown by hand. He would go and listen to music in the jukeboxes, and he was really interested in choro music.

The only type of music that his father approved of him playing was music that used the mandolin, which his father associated with his home country of Portugal. This “noisy business” of playing the cavaquinho, of playing the banjo, all that stuff was out for Vieira’s father. But he did approve of Vieira playing a more melodic style.

Vieira’s brother was a woodworker, and Vieira tells the story of going to an instrument shop in Belém and tracing the outline of a mandolin that they had on a piece of paper. So his brother was able to design one from scratch based on some of his observations and measurements.

Vieira has a real musical curiosity that really doesn’t know any national or stylistic limits. He tells this story of, in the 1950s or ‘60s, seeing for the first time an electric guitar in a movie, though he doesn’t remember the name of the movie. It was one of these summer hits where all the young men and women are hanging out on a beach playing guitar. So, there was an electric guitar in this. He liked the sound of it and started asking around.

It turned out that his brother knew someone who knew someone who traveled to Rio frequently who told him, “Yeah, the electric guitar is really taking off there. I can bring you back one,” so he brought him back one.

It came totally disassembled. He had no strings for it. He had no way of amplifying it, but knowing something about electronics, and, with the help of other people around him, he was able to put this thing together and make it work.

And this is the origins of what became the guitarrada…

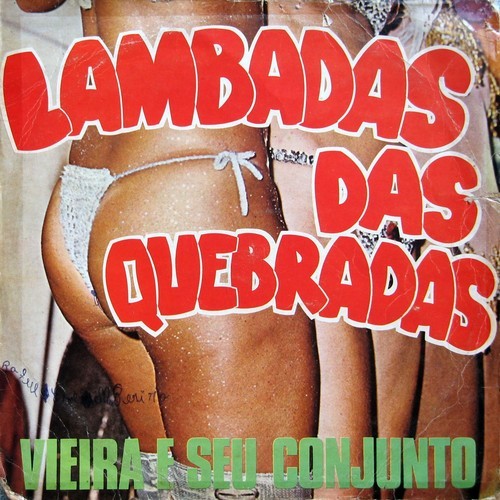

Exactly— it was around 1976, Vieira meets a producer from Belém named Jesus Couto, who invites him to record his first solo album, which was released two years later. This would be his first album, Lambadas das Quebradas— “Lambadas from the Backlands,” essentially.

This album they recorded in one sitting. Vieira says the horn players don’t show. The bass player had a two-stringed bass that he was using that he had built himself. It’s really done on the fly, but it’s a fantastic album that really touched off a whole series of subsequent albums in this electric guitar lambada style.

He continued to record and gig throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s. More recently, he ended up playing with the Mestres de Guitarrada for a number of years. Today he continues to do a lot of performances around the world with a band that his sons and his grandson play in.

And so, parallel to all this great music that’s happening, we have this other meaning of the word “lambada” which comes from an international dance craze that appeared in the late '80s and early '90s—can you explain for us how that happened?

During the ‘70s and ‘80s, there was a growing recording industry based in Belém. Lambada became kind of the stock in trade that a lot of local producers were scouting and recording—among other local styles like electric carimbó. The music industry at that time was arranged in such a way that it made more logistical sense for Amazonian musicians from Belém to tour and set up distribution networks into the neighboring Northeast of Brazil than it did to do those things in the rest of the Amazon.

This ended up creating a certain flux, a certain exchange, between Belém and the Northeast, where musicians would go and play in nearby Fortaleza or they would go to Recife, or they would go all the way down to Salvador in Bahia, places which were, at that time, kind of stopping off points on their way to the national center of Rio, which was really the powerhouse of the recording industry throughout most of the 20th century.

Within this sweep across the Northeast, the lambada ended up becoming very popular among Northeastern listeners, including in the state of Bahia, which during the late '80s was becoming more and more popular as an international tourist destination.

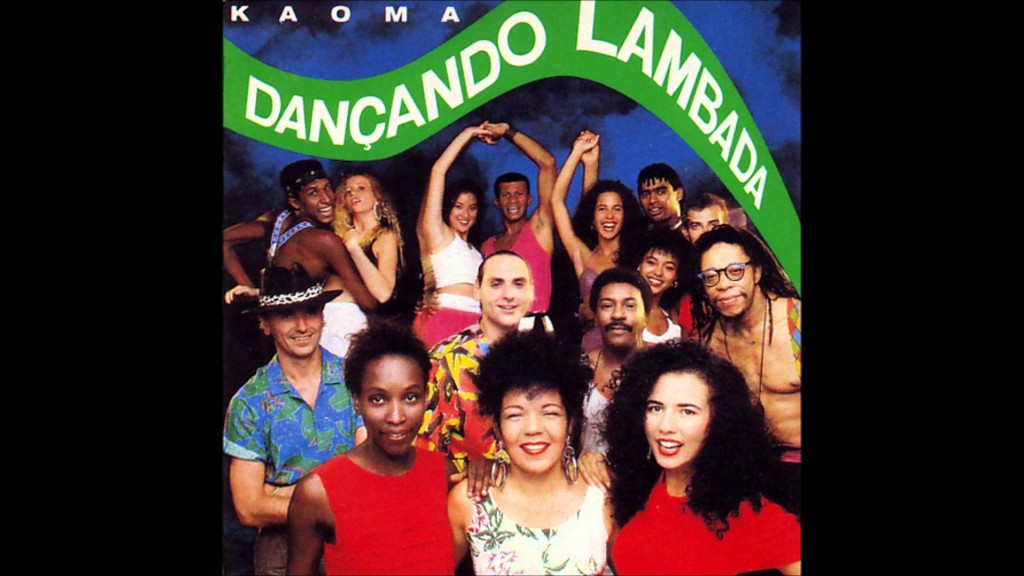

The story goes that there was a French producer vacationing on the beach in Porto Seguro in Bahia who heard someone playing this kind of hot, Caribbean-esque dance music and had the idea to form the band Kaoma that actually ended up drawing together Brazilian and Francophone Caribbean musicians. It became an eclectic circum-Caribbean, trans-Atlantic, part-French, part-Brazilian, part-Caribbean project that, for all intents and purposes, cut the Amazon out of the story altogether.

Kaoma was the band that really kicked off the international lambada craze, the forbidden dance, and they played an array of circum-Caribbean styles. It was very much in a kind of late 1980s worldbeat, world music vein.

And of course the song that cemented Kaoma as the face of the lambada craze was “Chorando se Foi,” which was based on a cumbia song by Bolivian group Los Kjarkas called “Llorando se Fue,” and this really became the cornerstone of the lambada worldbeat phenomenon.

I remember being in Austin, Texas, and hearing an ice cream truck passing by that was playing “Chorando se Foi” and being really blown away contemplating the kinds of musical currents that would make that song take its place alongside “Pop Goes the Weasel” as an ice cream truck song.

And how does this connect back to the original Amazonian lambada do you think?

I think it really doesn’t have much to do with the Amazonian style after that. I think people in Belém understand the “loss” of lambada so to speak to the Northeast of Brazil, to Bahia in particular, within a larger context in which Bahia was coming to assert itself as a major music production hub that came to eclipse Belém’s regional music industry.

However, I’d say that the lambada dance craze, the multiple movies that were made about it, the famous music video featuring Roberta and Chico—a blonde Brazilian girl and a black Brazilian boy who dance the lambada together—did end up having a huge effect on the international rebranding of the Brazilian Northeast as a kind of sensual, beach tourist destination.

OK, let’s switch gears to another kind of Amazonian dance music—what is carimbó?

Carimbó is a dance and drumming tradition that emerged in the northeast of Pará state and is closely associated with other Afro-Brazilian traditions cultivated by the descendants of the region’s African slave population.

It gets its name from the two- to three-foot diameter drum made from a hollowed-out log which is covered over with usually a deer or an anaconda hide and played horizontally by a drummer straddling it.

That's the foundation. From there, people have added banjo. They’ve added saxophone. They’ve added a lot of different types of instruments to that basic foundation.

Unlike other folkloric traditions from the Amazon that were related to Catholic saint day festivities, the carimbó wasn’t very highly regarded for much of the 20th century. In fact, one of the first references that we have to it in writing is an ordinance forbidding its playing in Belém. As with samba, carimbó’s a drumming tradition that was criminalized and repressed before it became “official cultural patrimony.”

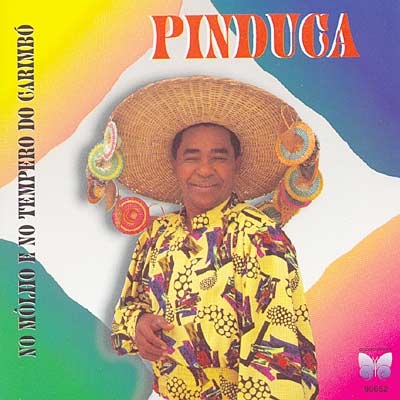

During the 1970s, that changed a bit as urban dance band leaders, like Pinduca, started to do kind of electrified version of the carimbó.

Teachers, folkloric societies, and so forth took an interest in the carimbó during the 70s as well, and it became consecrated as one of Pará’s traditional musics, a sort of regional equivalent to the samba.

So my understanding is that all this music from Pará— the lambada, the guitarrada, the carimbó—kind of dies down in the '90s and '00s, and more recently, there’s been this whole revival. How did that happen?

Yeah, there are a lot of pieces to this. I guess I could start by talking a little bit about the university-educated musicians who grew up in the '80s and '90s, who like their middle-class counterparts elsewhere in Brazil were really into rock 'n' roll.

They listened to Jimmy Page or Pink Floyd, but they didn't listen to things like the guitarrada, the lambada... although, they practically couldn't go anywhere in Belém without being exposed to it.

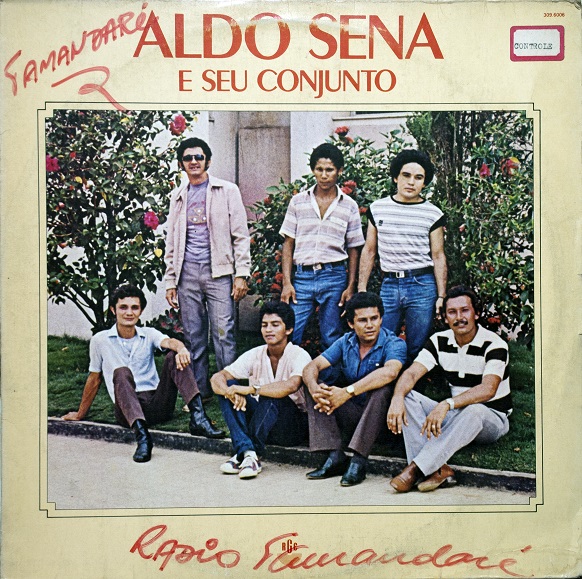

In Belém there are closed-circuit publicity radio networks that during work hours play music from loudspeakers throughout the streets of the different neighborhoods. These were constantly playing the music of Vieira, the music of Aldo Sena, of others who would go on to comprise this guitarrada revival.

And so these university-educated musicians were exposed to this music, but were fascinated by an American and Anglo tradition of rock 'n' roll that emphasized technical virtuosity in their solos. And they didn't really pay much attention to the local guitar traditions around them, which were built much more around arpeggios and which privileged elements of syncopation and swing for danceability.

Then comes Pio Lobato.

Yes—Pio Lobato during his time as an undergraduate at the federal university of Pará studying music, was really struck by the complete absence of local musical traditions in the curriculum. And so he ended up writing his senior thesis on the guitarrada, or what he called the instrumental lambada.

This is something that he, growing up, couldn't help being somewhat aware of, but he knew little about the life, the biography of Vieira and Aldo Sena and so he sought them out, interviewed them, and made an argument about why it would be important to include their guitar music in the music curriculum at the federal university of Pará.

Following on the heels of that research, he had the opportunity to work with both Vieira and Aldo Sena to develop this revival band called the Mestres da Guitarrada, the "Masters of Guitarrada." People have likened it to a Buena Vista Social Club of the Amazon.

And one of the important parts of this revival was reviving the memory of the story of lambada, reviving the memory of the story of Belém’s circum-Caribbean connectedness.

How did it take off from there?

So Pio Lobato got to work with Vieira and Aldo Sena and a carimbó banjo player named Mestre Curica who had played with the carimbó mestre Verequete. And one of their first major gigs was at Rec Beat in Recife in 2003 if I'm not mistaken.

And this was an important stage for a whole generation of university-educated, prog-rock-inclined youth, who, because of the circulation of Paraense music into the Northeast from Belém back in the '70s and '80s, had also grown up listening to this lambada sound, this instrumental electric guitar lambada. And so it had a nostalgic appeal, and this was the demographic that I think guitarrada was first able to tap into.

Not long after that, Félix Robatto, who was studying music at the state university of Pará, together with some people who would go on to become his bandmates, wrote a thesis on the guitarrada as well, and ended up forming a band called La Pupuña, which paid homage to the style of guitarrada.

And so those two bands—the Masters of Guitarrada and La Pupuña—ended up forming the cornerstone of what would become the Terruá Pará movement… I hesitate to use the word movement, because it was very much a top-down kind of thing. It was curated by the president of FUNTELPA, the state telecommunications foundation, with the express purpose of showing a sampling of current Amazonian popular music to the hip audiences of São Paulo.

But nonetheless, FUNTELPA played a really important role in providing the articulation between these different guitarrada inspired bands and other streams of local popular music, like tecno brega.

So they sent a delegation of some 60 musicians to São Paulo in 2006 to perform the first in what would become a series of musical expos that really helped to launch the national careers of a number of different musicians.

And so the issue then, with this revival, was that it ended up being very dependent on state government support. And when state government changed political parties, the momentum around this Terruá Pará movement kind of fell off.

This was seen as a project of the previous administration, and so of the many recording projects that were going on that FUNTELPA was opening up their studios to record, all of that was shelved. Some five years later the political order shook up again, and the Terruá Pará movement came back. It's kind of where we find ourselves now.

And so where does it go from here? Amazonian music has reached a certain level of popularity around the country, what’s next?

It's hard to know whether to give the pessimistic or optimistic reading on that. I think that there's some sense that Terruá Pará was very successful in putting Belém on the national music map.

But there was also some degree of trepidation about the media frenzy that happened around this new music scene, that this was going to be just one more exotic novelty from the periphery that would be consumed and discarded once a national listenership was tired of it.

And in a macro-sense there's some truth to that in the way that the music industry works, feeding on the new and on the different, though I think that a lot of the musicians don't have illusions of becoming huge superstars who’ll be able to retire on the money they make playing this music.

With of course the exception of Gaby Amarantos—who has become a huge star for bringing tecno brega to Brazil at large.

Yes and I think tecno brega's rise to national popularity—that rise of the tecno brega periphery to such a level of national prominence—a lot of people narrate that as an allegory for the rise of the new Brazilian middle class, the rise of the periphery taking its place, no longer at the margins, but really at the center.

There is something to that celebratory narrative, but there is some cynicism— some historically informed cynicism—on other culture critics' and musicians' parts, who take a more cautious view of the whole thing, and who are prepared for the bust after the boom.

Having visited Vieira over the years in his house in Barcarena, I can tell you that really not much materially has changed for him. A lot of musicians on the ground in Belém that haven't necessarily struck it big like Gaby Amarantos or Felipe Cordeiro, are looking at this cautiously as a chance to have another lottery ticket in hand, that it's a great opportunity to travel, to perform.

But will it last? That’s a really big question. As is the question of Brazil's economic boom, the economic miracle. In that sense maybe there is a connection between these new developments.

So, you say that artists from Belém, especially this new wave, are “claiming Caribbean-ness.” To close us out—what do you mean by that?

I think claiming Caribbean-ness in the 21st century for musicians in Belém is about representing the cosmopolitan nature of the experience of living there, which is so often thought of as a remote or provincial periphery.

Claiming Caribbean-ness becomes a way of incorporating a certain cosmopolitanism that the rest of Brazil can't lay claim to, because of the unique history of the Amazonian region. It's a cosmopolitan Caribbean-ness that provides a way of speaking back to this idea that Belém is the last place you can get to by land. That's only true if you're taking the perspective of the southeastern metropoles of São Paulo and Rio. Belém is the first place you get to from the circum-Caribbean and from the rest of the world, if you see it from their perspective.

![lambada_002[3]](https://afropop.org/migrated-uploads/2014/08/lambada_0023.jpg)