You can’t ask for better reception than the one that greeted ILe’s first album: NPR said, "The album established her immediately as a first-class interpreter of the classic sounds that flow through Latin America;” the New York Times praised it; it won the Grammy for “Best Latin Rock, Urban or Alternative Album” in 2017.

Of course even by then, Ileana Mercedes Cabra Joglar was used to winning awards. As a singer in the band Calle 13, she had already won three Grammys and 23 Latin Grammys—the standing record, by the way.

She laughed when I brought this up and asked her if anything less than two Grammys would be enough for her second album, Almadura. The 29-year-old singer and I spoke on the phone about the record, which just came out.

It’s a great album, with different threads of Latin American music—mambo, boleros, rumba—surfacing for moments and sometimes entire songs, but with modern production—electronic drums augmenting hand percussion, electric guitars trading barbs with horn sections. But play "spot the reference" too long as you miss the deep thematic material.

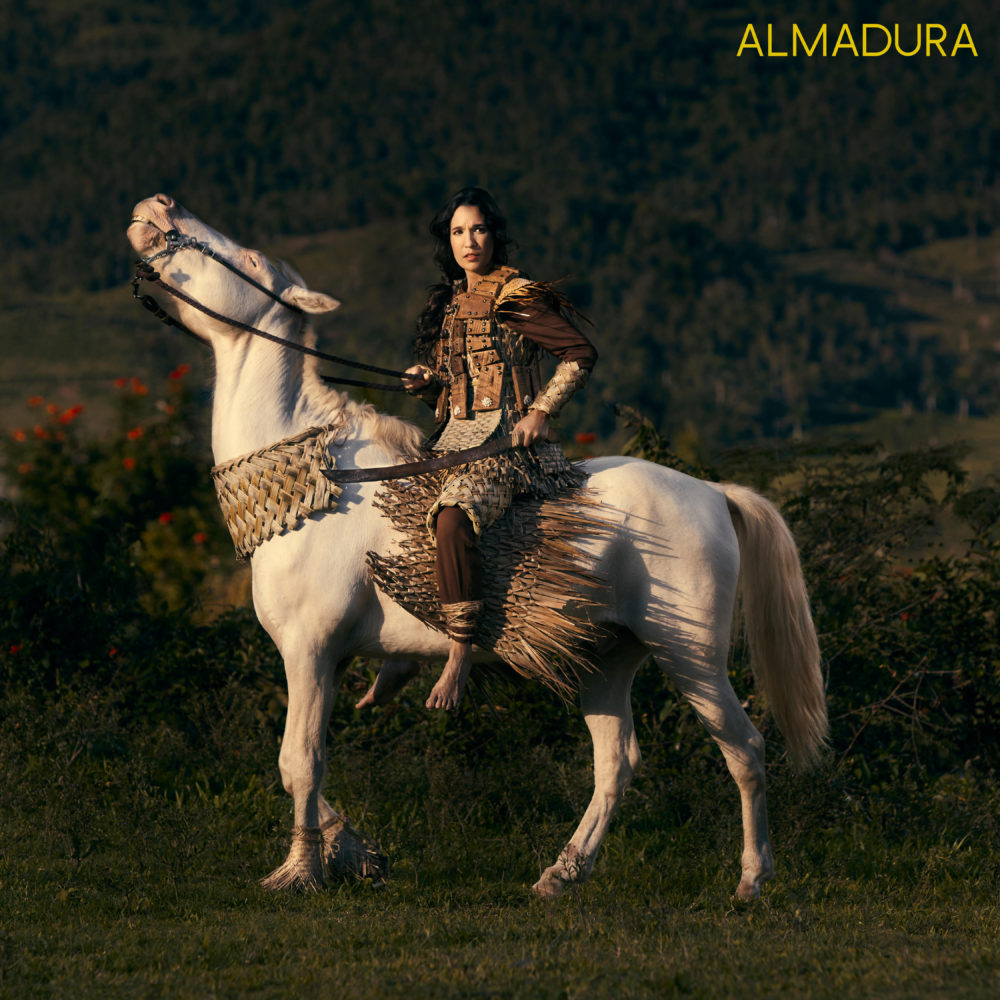

The title for ILe’s second album is a play on words—alma, meaning soul and armandura, meaning armor. The album starts with a song titled “Contra Todo”—“against everything.” Fighting the patriarchy and a colonial power that relegates Puerto Ricans to second-class citizens, it takes a strong soul to persevere in the world. Almadura is a battle cry, albeit one that's mixed with gorgeous arrangements, iLe’s dynamic voice, and a guest spot from Nuyorican legend Eddie Palmieri.

Ben Richmond: Congrats on the new album. You want to introduce the Afropop audience to it?

Ileana: Thank you! It’s my second album and it’s called Almadura.

Is it just a digital release now? Any plans for a physical one?

We’re working on it. For now it’s digital, but we’re working on at least some limited physical release or something.

This is your first album since you won the Grammy for iLevitable. If this doesn’t win two Grammys are you going to feel like you’re stagnating?

No, I don’t really care that much. It’s something that’s more mediatic and to celebrate and enjoy it a little while but it’s not my goal to win anything. My goal is releasing the album. For me that’s the biggest success because making and creating an album is very difficult to do and it takes a lot. So now knowing that the people are already listening to the album makes me very happy.

You won a bunch of Grammys and Latin Grammys with Calle 13 too. On the one hand you could say, “Oh the pressure is on me every time, the world is watching” or you could say “I’ve got the proof that I can do whatever I want, so the pressure is off.”

Maybe because I know already what it’s like, it’s not as exciting anymore. I know, I understand it more so I know it’s not a priority for me. Obviously it’s when something you’ve made gets recognized it’s always good but it doesn’t affect me negatively in anyway. I enjoy it if I win, if not, it’s great as well—I’m happy with the work I did already, so, I’m O.K. with that. It doesn’t matter. [Laughs]

It sounds like you’re in a good place with it. Let’s talk about the work. On past albums you had moments where you’d stop and be like “here is a bolero.” Did making this album feel less like “trying on genres?” Do you still feel like you’re trying on genres?

I really don’t think as much about genres when I’m working on the album. I try to figure it out later, you know? On the first album I know I like boleros and mambos and I think the first one might have a little clearer genre—what they are. But when I was working on it, I wasn’t thinking of it as much.

On this album I wasn’t either. The only thing I knew I wanted to do, was I knew it should be percussive. But since I don’t want it to be as pure with genres, that’s why I don’t know where to take it as much. I think that this second album is a little more Afro-Caribbean and the first one is maybe more traditional Caribbean music. On this new album, something I enjoyed a lot was mixing different African rhythms that we have in different countries, not only Puerto Rico, and trying to make a new rhythm out of it.

So, taking “Sin Masticar” has such a playful, classic melody on it. I can picture so many different arrangements under it—it’s got those good songwriting bones on it—how did you work out the beat you used and when that came in relation to melody?

Well, I think something I like is that I can see different ways of playing through the songs and this one, “Sin Masticar” I remember that Ismael, my coproducer, started with the rhythm at first. Only the tambour, the drum. And it took me somewhere. I was thinking, it had a lot of movement. But at the same time I was thinking about conforming, and here in Puerto Rico and I know in the rest of the world, but I feel a lot of lack of reaction when we need to react, and I started thinking about being hypnotized and paralyzed without any movement at all. And then when the rhythm started I wanted it to…working counter to the theme. The rhythm was quick with a lot of movement, but I wanted the song to feel the opposite in a way—a little slower, and the song was talking about the opposite of movement. I wanted that contrast. But yeah, I remember only having the drum playing and it took me to different places until I got to the one I like, and that’s how “Sin Masticar” grew up.

You started with the rhythm, then the theme, then melody and arrangement. Speaking of that push pull between something in motion and something static, you worked with one of the masters of that—Eddie Palmieri--on this record.

Yes. It was amazing. It was something that we thought a while ago about. You know as fans, myself and the whole family are fans of Eddie and the Palmieri brothers really. We were excited about the idea but weren’t sure if it was going to happen. For me it was incredible. Ismael worked that out until we could do the song together.

He, Eddie Palmieri, recorded his part in New York and I was in Puerto Rico but we spoke by the phone and we understood each other really well. I appreciate his touch and his way of playing and how he maintains it at 82. It’s great to have his aggressiveness being part of this album because it was perfectly fitted.

Have you had a chance to sit down with him in person yet?

Not yet! We saw him live in Puerto Rico once. It was many years ago and we shook his hand and met him but I didn’t even have my first album out yet. We met just as fans, but we haven’t met personally yet. I hope it does, but at least we spoke by the phone with him and it was a great conversation.

Are you coming to New York this summer at all?

We play July 10 at Summerstage as part of LAMC.

Let’s take a look at the bigger world. This year we’ve seen Juan Wauters and Helado Negro have released indie albums to what amounts to great acclaim in the indie world, meanwhile J Balvin and Bad Bunny continue to rule the pop charts. Latin music is more central than it has been. Have things changed in your world at all?

Yeah. It’s nice to know. It depends on the way you see it. In reggaeton and trap, most of these artists are from Puerto Rico and I’ve been listening to reggaeton since I was a little girl. It's been around everywhere. It’s nice to observe. Something about Latin Americans, we have something that people need. [Laughs] That’s why trap music for example was something very well known but at least here in Puerto Rico and other countries it wasn’t something people listened to as much until Puerto Ricans and Latin Americans started working with it. So it’s nice to feel now something like teamwork. Now North American trappers are looking for Latin American trappers and not the other way around.

It’s something people are beginning to know: it’s important to expand the musicality. And not just reggaeton, I use reggaeton as an example because it’s something that might feel limited music-wise—it doesn’t have a lot of instrumentation—but it does have something that people are feeling captured by and it’s something you need to analyze as well. It’s something I think through a lot. With the rest of the music it’s nice to feel that people from other countries want to learn more about because for me it is very rich; it has very many branches that you can work with and for me that’s a good feeling.

That barrier seems down a little bit and there’s more exchange both ways.

Exactly.

So who do you see as your peers—working the same areas as you and you hear them and you’re like "Whoa, wish I’d thought of that!"

I don’t know; I’d have to think about it. Usually the people I listen to the most and think things like “ah I wish I’d done that” are people who aren’t here anymore, and from other generations.

Especially arrangements that I like in salsa, something that I feel that is so hard to do these days, have a big orchestration and live and very raw is something I really enjoy from old salsa music, and I just like the reality of it. It’s something that I like to do with my own music. I like to keep it very real and raw to the listener because it’s something I appreciate from that music.

I like Ismael Rivera and he died already many years ago, but his music is still very alive and everywhere here. His voice was very unique and his arrangements of his music, he played a lot with folklore from Puerto Rico and adapted it to salsa music and he also had boleros and just his way of telling his stories felt very fun to listen to. It’s like the music that I most listen to, now I might listen to some newer music, but I don’t know if I feel the same connection to it.

I can see why Eddie Pamieri was a natural collaborator. Thanks so much for hopping on the call. Is there anything else listeners should know?

We’re working on the agenda of the presentations and on social media I keep everyone updated. So when I have something other than the LAMC show, I’ll let them know over there.