Joseph Shabalala swept through New York at the start of his 2004 U.S. tour, the first for Ladysmith Black Mambazo in some years. Sean Barlow sat down for a chat with the legendary South African musician. We are reprinting this interview to go with our encore of GOSPEL LIVE FROM SOUTH AFRICA TO ALABAMA.

Sean Barlow: Joseph, nice to see you. So you're at the beginning of a big tour here in America and you just put out a new album. Tell us about that album, what was the idea, the big picture with that album?

Joseph Shabalala: With the new album, we were lucky that the company, Heads Up, loved to produce this new album here in America. People are very excited and they still remember that Shaka Zulu, the album after Graceland , won a Grammy award. I'm sure that this is amazing.

SB: Was it recorded in South Africa? How did the thing happen?

JS: We recorded in South Africa and then the companies came together to talk about this. They worked very hard to tell the company that people here love Ladysmith Black Mambazo, why don't you send the record? And they sat down and talked about it, yeeeessss.

SB: What is the name of the album?

JS: The name of the album says: When you get low, Raise Your Spirits Higher, which means be higher than those things trying to oppress you.

SB: Hmm, and that's a song on the album as well?

JS: Exactly, the first song is saying the same thing.

SB: Tell us more about the lyrics, what are the lyrics saying?

JS: It means try to be taller than those problems [that effect you]. Take your way higher and higher, just like those people who were following that king, Jesus. Just do that, go higher and higher, and you'll conquer everything. And another song says you can bring together something that you can afford to do it, but all others just leave it for other people. And another is in English, it says [SPEAKS ZULU] "Watch out, don't take everything for others. Stay in your important thing and share with others what you have."

SB: So it sounds like a lot of the songs have a social message something like, "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you."

JS:That is something, even myself, when I listen to the album I say, "Oooh, this album is leading the people to a better place, go higher and higher." And also I love it when they talk about marriage. They talk about "um-sha-do," marriage. Don't forget that the marriage is from somebody who loves you. Take care, always tell him that, "I have a problem." He will solve that problem. There are many songs, I can't remember… It's a very good album, especially when it says our country will become whatever our children make, which means that we saw a new South Africa and we were happy. And then, let us build the country now. Because all along we were crying, now there are no tears. Let us work together. Our children will be very happy when they find that fathers, grandfathers, they were working very nicely. Let us use that heart, that inspiration, to do something good for the next generation.

SB: That's beautiful, and do something for the country. So let's talk about that for a little bit, because you know the reason I'm going to South Africa and interviewing musicians like yourself is to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the transition to democracy, April 1994. Bring us back, where were you in April 1994 when the election took place that elected Nelson Mandela?

JS: Oh yes, I was at home. I was lucky to be at home. I remember when I was running up and down trying to find a short line. There were huge lines of people going to vote. I drove to Durban and found a shorter line and then I voted there. That night when I went to sleep it was like I was in a new world. We were very happy. I remember Mandela took an airplane all the way from Johannesburg to Natal, because he had a good friend that passed away. He then went to vote and took another airplane back to Johannesburg. That was a lovely, beautiful day, which I think this anniversary now. Ten years. It would give us more power to carry on and correct if there are mistakes.

SB: That's beautiful. Great story. What about inauguration day in May? Were you there on inauguration day when he made a speech and accepted the presidency?

JS: Yes, aaahhh, I can't forget that. I was in Pretoria in front of him, I was singing in front of him. I remember when I saw Danny Glover, he came and hugged us. Everything was there, the officers of those big people who were coming together to tell others, "Let us oppress these people." They were just outside our changing rooms. We were changing there and we were thinking maybe they could come in and shoot us, because we know that they don't like it. But that day was a wonderful day for black and white, Indians and colored. People were very happy! There was another place down there where people were singing. And we finished down there after Mandela's speech. We ran down to sing for the people. Many people were there! It was just like new life. I don't know whether people still remember that day.

SB: Well you've helped us remember it. I can just see the energy in your face and in your voice.

JS: Imagine, the people we have not seen them 30 yrs., 25 yrs., 19yrs. Others we saw them. We saw them and we were just like laughing, tears, crying for joy.

SB: Mmm, that's great. Now let's go 10yrs. forward to 2004. We're celebrating the anniversary. You already mentioned some of the triumphs, some of the mistakes. Could you give the big picture of where South Africa is now? What's changed, what's different now than during apartheid times?

JS: Mmm, people are still homeless. Some other people get better, jobs are going down, coming up, going down. We need neighbors and friends away from us to come together and do something better. Jobs, schools, new education, to teach our friends who were teaching us, all those things. We have to do it. Not to be just like a baby who loves to do something by himself and cries when it needs his or her mother to come and wash that table or that floor. But now is the time to concentrate on the people, forget about politics, work for the people very hard. Now is the time for our friends to come and help us and we can give them something, what we have. And they can give us the experience they have of how they do good things in the place, or to raise funds. Like in my mind I have only one thing I think is very important, to teach the people who were away for so long from their culture. They forgot even how to plow, how to drive the oxen. Because many things are in this world, under this world. The gold is there, everything is there. But we need one another, that experience of doing things together, black and white, Indians and colored. Not just like your children at home, sometimes you give them food and they start arguing about food, any you stay stop, stop. We need somebody in and out to say "Hi guys, don't do that." It looks like the government is trying to do that, but it looks like it's lonely. Other people are lazy, maybe they sit down say, "Ok, we have our government. We just chose them to lead us. Why don't we help them? Let's help one another everywhere." Forget about Zululand, forget about Xhosaland. I sing Zulu songs, I sing Xhosa songs, German, a little bit of English, trying to show people, "Let's come together and work together. We have only one father, he wants to see us together. That's all."

SB: Could we hear the different sounds of the languages you sing in, for the radio audience?

JS: [SINGS] That is Sotho. It means, "Something here, father and mother. We remember tears all the time. Lets come together and help our people. And then in Zulu--I always sing Zulu, forget about Zulu, that is my language. But when we sing in Zulu we talk about culture, we talk about Xhosa, Sotho, Zulu, we talk about Africans. That is our culture. When I said I was trying to boost the culture, I was appointed to do that. At night when I was sleeping, I wake up look at the people, and I think, they don't know who am I. They always call me "Bige Zizwe," which means "take care of the nation." That is my Zulu name. But today, I'm a new person because there is a sound, always when I'm going to sleep, a sound, for six months. Then after the seventh month, I started to see these people. Who are they? They were teaching me how to dance over this sound. So I was thinking, I'm looking for somebody who I can work with. The people they said, "Are you mad, are you crazy? You didn't sleep, you were thinking about music. Don't do that. We will take you to the doctor. The doctor will cut off one of your veins. You have many veins." And that's why I went to the young people and talked to them. I worked with them for six years and they gave up. They said, "No, no, it's difficult, you always change, change, new song, new song, let us stay to our traditional songs." I said, "These are our traditional songs, but we want to send the message to the people." And they said, "Why?" We must talk to the people. And then here comes two guys from Mazbugo Femeli. According to our culture I call them brothers because our fathers are cousins.

And I talk to them and they say, "Yes! It's up to you. We don't know what you're talking about, but we have voices. We can do whatever you say." And I was very happy. This is the time to build the school, to teach the people and to teach one another. People lost how to respect one another--that's all. Once you have many things; music, lyrics, talking about inspiring oxen, many things, they will remember. Black Mambazo, remember that. Many people now in Africa have started to respect themselves. That is the way. Forget about politics. Work with the people. I was in Mandela's big concert about AIDS and I said, "This is wonderful." Because even myself in the early time, 2001, I just bought a tent and told the pastors, those who have energy to preach, "Go outside with the tent around our place, Johannesburg, Natal, and tell the people how take care of themselves, about AIDS." And they did that. At night from 8-10, they were preaching. Daytime, calling the children from school and then inviting the doctor to teach them about it. This is another fight, and we must win this fight. And they did that, which is beautiful.

SB: And necessary too.

JS: Exactly. Exactly. I'm sure that we're going to carry on doing that.

SB: You bring up an interesting point about reminding people about who they are and their culture. I know you've always felt strongly about that. There's an interesting thing I noticed when I first went to South Africa in 1988. I had seen you on the Graceland tour in 1986. And at the time there was this whole tradition of Bantu radio (ethnically based), different radios, and the homelands and so on. And I thought to myself, "Wow." Because other places in Africa they are very proud of being Wolof and Senegalese or being Bambara and Malian. They kind of co-exist. Because the apartheid people used the tribal identities to separate people. I thought it will be a sign of maturity when South Africa can be proud to be Zulu, proud to be South African, and there won't be a conflict between these things.

JS: I agree with you, because I love that. When I was singing I was trying to bridge that gap of people saying, "Oh, you don't know how to speak Zulu, stupid, Swazi, stupid, Xhosa, stupid." No, we are all important. We must sit down and do something beautiful. That's what I was trying to do. Maybe I can say this, I failed in one thing, because people they deny the sound that came with it. Therefore it changed to be like charity begins at home. I come back to my brothers and ask them, "Please," and they said, "Okay, we are here with you." Other people they come and listen and say, "Aahh, it will take long time to get money." I don't want money. I want my people to have their roots. And now they are running after me and saying, "Eh, there is money." I don't like that. Don't say there is money. There is culture, my father is here, my mother is here, my sister is here. Eeeeh eeeeh. We must try to create all those sounds.

So far I'm singing with Black Mambazo, only boys. But early times, while I was at home, when I stop the fighting--two nations were fighting one another--I was singing with the ladies with their beautiful voices. Ladies are very, very strong when we talk about music. When you give them one voice, 4 or 5 of them, they don't clash. But here with the boys, they try to imitate the lady. When you put another one it's difficult. But Mambazo now they are getting up and up. We have two altos, 2 tenors. It's coming, but we don't have a school.

SB: You mean a school to teach the…

JS: To teach a choral music academy. But that one, it's there where we learn everything about our country. After we put the cows at that kraal and then at the corner boys come and singing there, girls come and singing there together. But this separation make us sing alone.

SB: What's the separation? I don't understand.

JS: The girls were not allowed to come to the mines. We left them back home. And we remember, "Oh, that lady back home she was singing very nice. One of us, I can match her. I can imitate her and the music will come better." And the ladies were lost when we came back home and sang for them. They said, new style. And they tried to imitate us and we tried to imitate them. Which is good, it's good. It's that what we call "cacha."

SB: Good, the general tradition you work with, is it "iscathamiya," is that how you say it?

JS:Exactly, iscathamiya, then there is a shishameni, and mqashiyo. There is guitars inside that. And amahoobo, it has a lot of energy. Take your mind, remember back, remember forward. Some people call it war songs. It's not only war songs. There are war songs and there are songs to praise the king, praise the mountain, praise the rivers.

SB: Can you give us an example?

JS: [SINGS] That song is talking about if you feel like you don't want to respect me, all let's take only a stick, not guns, not killing, but take a stick and I will show you. Look, look, it going down. It's going under your armpit. Look, watch out, you open your head, but not there.

SB: Great. So, Joseph, in Natal or throughout South Africa, is the iscathamiya tradition alive and well? Are there young groups doing it, coming up?

JS: Oh, now you will find it even in Zimbabwe, in Cape Town, everywhere. As many as possible. Another one they used to come and ask me to workshop them, they call themselves Red Mambazo, White Mambazo, Women of Mambazo, around the world. But they sound very beautiful. Don't forget maskanda, men singing alone with the guitar. You can see him across the river going to work playing this guitar just by himself. …All those types of music.

SB: And that's still happening?

JS: Oh yes, still happening. Although the maskanda, now they sing with many people. As usually, like me I was singing maskanda by myself, until the sound came that was something more than that. You can do it, many sounds.

SB: I remember the maskanda starts with the guitar, then right in the middle….(sean imitates singing)…there's that big rapping.

JS: Hahaha, exactly! Because that rapping is to praise. Maybe you can praise your father, you can praise your Mother, you can praise the region. I come from there, I raise up there. He was a good man, here's my king next to me, here's a person who works with the king… they praise. You call rap, but he can tell you who he is, his surname, his father, grandfather. Where am I? Those things are beautiful, it makes you know him from that time.

SB: Great. Joseph. One other question, so the Red Mambazo, White Mambazo, and all the other people who were doing it..

JS: [LAUGHS] White Mambazo…

SB: is that white people who were doing it?

JS: No, just White Mambazo. In fact, White Mambazo was my children, I named them "White Mambazo" the time when I joined the church. I felt like my heart, it's night, now it's daytime. I say I have Mambazo, but white. Because when I started Mambazo I was just like a politician, but polite and giving them power and strength. Like you can do something, carry on. But polite, yes.

SB: This summer I think I saw a group called "Ladysmith Black Mambazo Jr.," led by your son.

JS: [LAUGHS] That was White Mambazo, but they changed it to "Jr." because the culture here. They thought about color. I was not thinking about color. Yeah, I was away from that. I was above politics, I was above hating somebody. Even revenge, I don't have that. Yes I know how to move that thing. My blood is very strong to take the thing and come with the answer and move it away.

SB: Good, good. I guess my question is, are those iscathamiya groups an active part of the professional recording scene? Can people make CD and sell them and is there a lot in the marketplace? Is this sort of part of the music industry in South Africa?

JS: Exactly. There are some of them--not all of them--who are professional. They have been away from home, Europe, here in America, some of them. But there are many of them. Therefore it is difficult to record all of them because some of them, they are imitating one another. There are many musicians, not so many in the market, but many of them are there now.

SB: Now Joseph, here we are. We talked about 1994, 2004. Let's talk about 2014, ten years from now. What are your hopes and dreams and fears about where you see South Africa going?

JS: I have a hope, but also there is fear. But the hope is that once our people tend their mind away from politics. Like Dr. Nelson Mandela, to work very hard for the people, forget about who he is, just work very hard. Forget about who's going to choose me. We're all chosen, from home. We work very hard. I think if they deal with politics, we are going down. But if they raise higher than that, raise your spirit higher, they are going to conquer. They're going to love one another and we will see and enjoy a new South Africa.

SB: That's your hope, yeah?

JS: That's my hope.

SB: What about culturally, musically?

JS: When we talk about cultural music, we talk about blood, we talk about something in our mind that we learned when we were young. Now we are teaching our children like the early time when we learned this. Therefore, work very hard to produce your dream. You can start imitating and then after that, ask yourself this question: who am I? My surname? My father? And then you can work with other people because you have something.

SB: Great, and also you mentioned you have some fears too. What are your fears about what's going to happen 10 years from now?

JS: My fear is that we stick too much to politics. Because sometimes politics separates people, makes people hate one another. All along it was just like tradition. I know your surname, you have your brothers, I have my brothers, but some way somehow we get together. I'm afraid of that separation, of being proud that I'm Joseph Shabalala, everybody loves me, I don't need nobody to follow me. That's a danger. Ten years from now if people stick in that… I don't know how to call it, it's just like Mother and Father always scold the children: "Why are you crying, why are you crying?"

"He take my food, he take my food!"

"Stop, sit down and eat together."

Once we don't want to listen, our culture stops. Sit down, eat together, share that meat, share that maize. Share your things. Are you drinking something? Ye, share that. That would be wonderful.

SB: Great, great, beautiful. Now that you have the album in your hand, do you want to tell us more about some of the songs?

JS: Yes I'm glad now I have the album in my hands. This one says "Uqinisil' Ubada" In fact when I say "Ubada." I mean nobody has a truth except my father. When I'm talking about my Father, I go higher as the song said, raise your spirit. My father, and you can say the same thing. My father and they can say the same thing, and then we start to respect one another. "Uqinisil' Ubada." It means, "My father always has truth."

SB: And "Baba," you hear that all throughout Africa, Baba means father, correct?

JS: Yes, Baba means father, but to this song here it's talking about God. That's your God, that's my God. When we start arguing be proud of our father. And we are proud of our spirit.

I like this, "Iyahlonipha Lengane." Yes, I like this one very much, "Iyahlonipha Lengane," which means, "Oh, this child. Respect, this child have respect." But I'm not just talking about the child. I'm talking about to respect one another whether you are 24 yrs old, 30 yrs old, but to respect one another. Whether you're a pastor, a king, a government [official], but to respect one another. That thing will never kill you. People will talk about you: "He respects. Let us go and help him." But if you don't respect, nobody will come and help you. "Iyahlonipha Lengane," a respectful one.

"Black is Beautiful." You know that?

SB: Yes, I heard that.

JS: "Black is Beautiful." Black is beautiful, but first he talks about all colors. But because I'm black I said to be with these colors I can make it rainbow nation, trying to bring people together. And it says that rainbow nation black and white, forget about, use your mind, your brain, work together. Music knows no boundaries. It happened when Paul Simon came to South Africa. It was a long time, but somebody was pushing him and there's no way to stop it. And also the music builds bridges between people who are here in America. It means that music is just not music. Let us respect music. It's God himself, his spirit. But when God pours his spirit to you and you pour another spirit, that is not right, let's forget about that okay.

Oh, let us talk about this tribute. I remember one day in 1994, I came here with my children, my grandchildren. And Paul Simon wanted to see them, he take them with his limousine, we went out to eat and go back to his home and he had them singing. And he touched the strings and said hey they are in the chords. And now they sing here, I just record them. They were just playing and I record them, and we call it "tribute" because they are talking about their grandmother who passed away. And they gave me strength. She's still in your heart, don't worry. But those jealous people they thought they would destroy the Shabalala family, you hear that. The young ones, that is a tribute to their grandmother.

SB: Your grandchildren.

JS: Grandchildren, yes.

SB: I was so sorry when I heard that story [about the death of your wife].

JS: Oh, God is wonderful every time. The Bible says don't revenge. I can kill him, I can kill him. And here's a big word. No revenge. And I said to him, "Sit down, wait for God to say something--that's all.

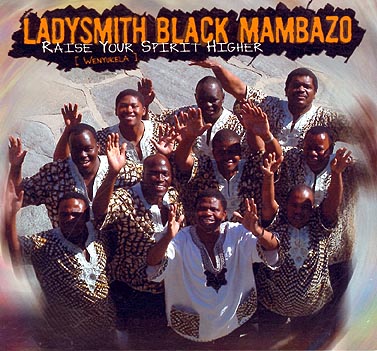

SB: Great, well that was a really great tour of your album. And this picture is the group?

JS: Yes, that's the group. We took it here in Los Angeles.

SB: How many are original members from the group?

JS: I can recall only one original from the group, but early time, before we record. Yeah, 1969. This tall man from Mazbugo.

SB: What's his name?

JS: Albert Ma-ze-bugo, and his brother was singing high part. It was just like when people want to give money to the person who take care of the group and they say "could he please tell him to come and sing with us?" and I say No, talk to him. And he say "No, I'm at home, you want me to separate me with my brothers?" Because the high part was something unbelievable. Now the one who sings the high part is my son, the youngest.

SB: What's his name?

JS: Tommy Shabalala, but if you want to bite your tongue, "Tomsang" And there is another one, I didn't say it because my eyes are not quick to see. That one is, we sing in our way about what happened in the early times. That work is from the early time when people were drinking and jump up and down and praise one another. And there was a prize. Now the people don't know what it means. Because tradition is our father, our mother.