Kelly Askew is a professor of Anthropology, and of African and Afro-American Studies at the University of Michigan.

She lived in Tanga, Tanzania, studying taarab music from 1992-95, and published “Performing the Nation: Swahili Music and Cultural Politics in Tanzania” in 2002 (University of Chicago Press). Banning Eyre interviewed her in August, 2005, for the program East African Taarab. Here’s the complete text of their conversation.

Banning Eyre.: Welcome to Afropop Worldwide.

Kelly Askew.: Thank you. It's a pleasure to be here.

B.E.: First, why don't you tell us a bit of your story as a musician and scholar, and how you ended up in Tanzania.

K.A.: I started playing piano when I was about seven years old or so, and continued all the way through high school. I attended a school for the performing arts in California, where I grew up, in Los Angeles, and continued on in college as a music major at Yale University. But I also discovered in college anthropology, and discovered I had a second love in life, and decided to find a way in which I could merge my two interests. Hence ethnomusicology, which became my application.

B.E.: And Tanzania?

K.A.: I ended up in Tanzania because I went to Yale, which has a very esteemed African Studies program and they teach Swahili, although I thought my heart was in West Africa. Originally, I thought I was headed towards India. But I discovered that the Swahili program was too good to pass up, and that there are Indians in East Africa as well. So I thought my original project was to study Indian music in East Africa, and try to see whether there was any sort of interesting hybrid stuff going on there, only to discover when I first went to Africa as a Junior in college for a summer project, that the Indian community is very purist about their music. They import the musicians for their events, and music is one of the ways that they maintain their separateness as a community. So what was more interesting to me was taarab music, which I discovered on that same trip in 1987. So this is Swahili coastal music, but very, very welcoming of any kind of musical influences from anywhere abroad, including the West, India, and the Middle East. It's very much an amalgam of all these different musical traditions.

B.E.: So that quality of openness and inclusiveness was more interesting to you as a scholar?

K.A.: Yes. The music was a little hard to get used to at first. Just because of the different aesthetics, and the preparation that I had as a classical pianist. The melodic structures were quite different. Of course, the rhythmic structures were different. Everything was different about it. The quality, the voice, the timbre. All of that were things I had to get used to. But once I did, I fell in love with it. And 18 years later, I am still working on it.

B.E.: Some of our listeners may be confused about the term “taarab.” We’ve talked a lot about tarab, “the art of ecstasy in Arabic music,” to use A.J. Racy’s nice phrase. This is something different in East Africa, isn’t it?

K.A.: Yes. The word itself means "to move the heart." It means to feel feelings of rapture and ecstasy, and it’s often used as an adjective in describing other kinds of music outside the East African phenomenon. When you speak about any form of Middle Eastern music, we can talk about it as having evoked taarab in them, or being a great example of taarab. But when we speak about taarab in East Africa, we are speaking about a very specific form of sung, Swahili poetry, that emerged… at some point in the 19th century, and became very, very popular in the 20th century, early 20th-century and into the late 20th century.

B.E.: That’s great. Help us put East African taarab in a historical context. Let's start with a little pre-colonial history. What we know about Tanzania before the Arabs arrived, and then you can bring us up to the Arab, and European phases.

K.A.: Tanzania as it is now only came into existence in 1964. Before that, it was part of the Bantu area of Africa. The Bantu language family originated more in West Central Africa, and the Bantu people spread out through eastern, western and southern Africa. So Swahili is a Bantu language in its noun and verb forms and its grammatical structure, and there are over 120 different ethnic groups in Tanzania, which makes it very diverse, especially compared with some of its neighbors. So, for instance, in Zimbabwe I believe there are two major groups, the Shona and the Ndebele. And in South Africa you have 10 or 11 national languages. Compare that to Tanzania with 120. It's quite a diverse place.

So, you had various types of political organizations, you had some kingdoms, and no one major group that really dominated, or even two or three. Sukuma were pretty powerful, and Nyamwezi. They controlled trade routes. But the Swahili people who grew up, sort of developed or emerged along the coast. Swahili, the term, comes from the Arabic word sawahil, which means margin or coast. So the Swahili are the people of the coast.

It also comes from the word sahel, which again means on the margins, sahel being the border of the Sahara Desert. So the Swahili are the people of the coast, and they really emerged as an economic power in being able to control the trade between the African hinterland, the overland caravan routes, and also the ocean trade, crossing the Indian Ocean. They were ideally situated to exploit both ocean and land routes of trade, and they did very well for themselves, developing this wonderful maritime but land-based economic trading culture that still had some agricultural elements to it as well as fishing communities and things like that.

The Swahili have been documented for at least 2000 years if not more. Some archaeological evidence implies that there were communities going back as many as 3 to 4000 years ago, and then Arabs started making their appearance in the area soon after the death of the Prophet Mohamed, coming down to proselytize, to convert people to Islam. And then the Portuguese appeared with Vasco de Gama. In the late 1400s, 1498. So Portugal entered into the region as a colonial power, only to be supplanted ultimately by Oman, and then Germany, and then England.

B.E.: So you had some 3000 years of what we call Swahili culture, but the name “Swahili” didn't come about until the Arabs came about in maybe the eighth century, maybe even later. Is that right?

K.A.: Even then they didn't really use that term. They used more the term Zanj.

B.E.: So Zanj is older term for Swahili?

K.A.: Yes. They referred to the coast as Zanj. They also referred to it as Azania. Ibn Batuta wrote about it as Zanj.

B.E.: And he was writing in the 14th century.

K.A.: That was 1331. But Ptolemy wrote about it as Zanjian in about 150 AD. And also the anonymous writer of the Periplus, in about 48 the referred to it as Azania.

B.E.: So what is the earliest use of the term Swahili?

K.A.: I don't know that we know that. But because of the word meaning coast, people from outside simply referred to as the people from the coast.

B.E.: When we talk about Swahili culture today, it is both an island or coastal and the mainland phenomenon, and somewhat uncomfortably so it seems. This is jumping ahead a little bit, but talk about the Swahili identity today.

K.A.: Well, there aren't that many people who self-identify as Swahili, ironically. This actually served nationalist purposes later on, which we might talk about. Swahili culture doesn't have the same rigidity to it, or concreteness, as many other ethnic groups. So for instance, from Tanzania, you might talk about Sukuma culture with more concreteness. People would identify as Sukuma, they would identify as Nyamwezi, they would identify as Chagga. But people don't often say, "I am a Swahili." They will say I'm from the coast, or they will talk about the city from which they are from. Some people from Mombasa, Kenya, talk about being Sefita. People from the northern canyon coast, talk about being Waahmu. People from Zanzibar call themselves Wanguja. Swahili has oftentimes taken on negative connotations, which is why people don't self identify as such now. When people talk about, "Oh, he is such a Swahili," the connotation is that he's shifty, or not fully honest somehow, deceitful, not somebody who is straightforward, somebody that you would want to deal with.

B.E.: That's interesting. I wasn't aware of that. When you think that came in? What is the history of that?

K.A.: If I would hazard a guess, it has to do with the economic position of the Swahili, being in that position to negotiate between Inland traders and overseas traders. Everyone had to place their trust in these middlemen, and then not really deal directly with the purchasers of their goods, or the sellers of their goods. So, maybe because of that, people were not 100% sure that they were being told the truth by that middleman, having to invest faith in that person, and knowing that people are in it for their own profit as well. The term has over time also had multiple meanings attached to it. In political circles, people would identify as Swahili as a way of sort of taking on a nationalist persona, not a tribal persona. So there have been occasions when, the first president of Tanzania Julius Nyerere, for example, said, "I am a Swahili." Even though it’s well-known he's not from the coast at all. In fact, he's from the place farthest away from the coast, a small island in Lake Victoria. He is from an ethnic group called the Zanaki. So for him to say he's Swahili, clearly this is not in an ethnic sense, but in national sense.

B.E.: That's fascinating. And he did that as part of his political vision of unifying people, right? You write in your book that Nyerere succeeded in Swahili-izing—if that’s a word-- the country more than many neighboring countries. He wanted to create a national culture, and this struck him as a good way to do it. Is that correct?

K.A.: Correct. The advantage of having Swahili be an ethnic term that is not necessarily a positive one is that it was lying there to be used by others for broader national purposes. So that is what Julius Nyerere did. He took this name, this label, and this language. The language is the key element there, because by that point, due to the caravan routes, due to the importance of the Swahili middlemen in those routes, the language, Kiswahili, had spread far and wide along the caravan routes, and beyond, up and down the coast. So you had this national language, essentially already in use, that was far beyond anyone ethnic area, that would be usable for nationalist, unifying purposes, when you are a new country that has just come out of this difficult colonial history, and you've got 120 ethnic groups that you've got to convince that they belong to something bigger than themselves. So Julius Nyerere did tap into that, and because the Swahili themselves don't affiliate with each other in any sort of political or jurisdictional, economic sense, as a unit, it made it very easy to use Swahili without being charged with favoritism, saying that you are elevating one group over others. Because there was no Swahili group there to be perceived as favorites.

B.E.: That explains a lot. Let's now shift our focus to taarab music. Maybe as a setup, you can tell us how it came to be that in the early 19th century, you had an Omani sultan in Zanzibar.

K.A.: The history of taarab, officially, began during the reign of Sultan Barghash of Zanzibar. Now, how did Zanzibar and up with sultans? I mentioned briefly that Oman came in as the colonial force. They routed out the Portuguese from East Africa, when people from East Africa went to Oman and asked for assistance to come and take out the Portuguese. They didn't like being under Portuguese rule, and Oman had succeeded in routing the Portuguese in their neck of the woods. At this point anyway, the Sultan of Oman, a man named Seyyid Said, he derived a lot of his wealth already from the ocean networks that ships travel between East Africa and the Middle East and South Asia. By that point, East Africa was a major supplier not only of ivory but of gold and rhinoceros horns, Amber, precious luxury goods that could not be obtained elsewhere. The ivory from Africa was of higher value than the ivory from India. It is harder I believe. So there were certain goods that he was already capitalizing on quite heavily. So he realized at some point in the early 1800s that he had to go and protect the trade roots, and being out on the tip of the Persian Gulf, he was quite far from where the action was. He could be encroached upon by other powers. So he picked up his entire retinue, his court, and moved everyone to Zanzibar some time in the 1830s, and established himself there as Sultan of Zanzibar and Oman, leaving behind in Oman a son of his to control that part of his domain.

So in Zanzibar, upon his death, he had numerous sons. Although he had just one wife, he had numerous concubines and lots and lots of children. There was a series of successions over the throne, and one of the sons that came to power was a man named Barghash. He did not immediately succeed his father. He tried to, but was usurped by another brother, and sent off into exile for having attempted to take the throne by force. When he was in exile, we're told that he spent quite a lot of time in India and traveling the world, and he saw court life in other parts of the world and decided that when he would return to Zanzibar-- and he was quite sure that he would at some point return as Sultan-- that he would develop a court life like he found elsewhere, a major component of which is music. There was court music, and court musicians in other courts that he visited, so when he became Sultan, as he did in the 1880s, he brought musicians from Egypt to come and play court music for having and his court, and he also sent musicians to be trained in Egypt, and he ordered instruments and created this court music that was pretty much an Egyptian court music transplanted to Zanzibar.

However, that didn't last very long, and over time, the music became very much indigenized. Instead of singing in Arabic, people started to sing in Swahili. Instead of using exclusively Arabic rhythms, and the maqamat, or modal system found in Middle Eastern music, they started incorporating African rhythms, and also a lot of Western rhythms, foxtrot, waltzes, cha-cha-cha. In the early 1900s, these were the popular rhythms in taarab music.

B.E.: So you are saying that the Arabic modes and rhythms didn't last long it all. It is not a recent thing that they fell out of the music. It seems that happened even in the first 20 years.

K.A.: Yes. Some of that has remained, especially in the form of the bashraf. The bashraf are the instrumental interludes that start any given concert in Zanzibar. It's really a Zanzibar and possibly a Dar es Salaam phenomenon. Those two areas have retained more. And the proximity of Dar to Zanzibar of course is a factor. Today, it's a two-hour boat ride. It's 24 miles through this short channel. So they have retained the bashraf, which typically does use Arabic rhythms and Arabic maqam. Beyond that, there's not much that has been retained. Although, in Mombasa, Kenya, there is still some Arabic taarab that is performed today to my knowledge.

B.E.: Politically speaking, this Omani Zanzibar sultanate exercised power on the mainland as well, didn't it?

K.A.: I talked about Sultan Seyyid bin Said, the first Sultan of Zanzibar. He really was able to build up the economy of Zanzibar such that they used to say, "when the pipes play in Zanzibar, people dance at the lakes," meaning Lake Victoria, and Lake Tanganyika, all away across the other side of East Africa. Sultan Said introduced plantation agriculture, and developed the clove industry in Zanzibar, which became its prime product for 100 years or more, and really developed Zanzibar into this huge economic force. His son, the one who is often associated with the start of taarab, Barghash, ruled Zanzibar from 1870 to 1888, and he inherited this powerful domain that his father had built-up and was able to continue it. But it was substantially weakened, because by then, the British had come in and started to employ indirect rule by claiming Zanzibar as a protectorate, and ruling through the Sultan, but really being the power force at that point.

B.E.: How to slavery fit into this story?

K.A.: The East African slave trade started out later than the Atlantic one. Slaves were traded on the East African coast, but they were not a commodity of importance until quite late, relatively speaking as slavery goes. The West African slave trade was up and running certainly in the 15th through the 18th, even 19th-century. But in East Africa, slaves didn't become a commodity of importance until really late in the 18th and into the 19th century. Slaves did not become a commodity of importance until the reign of Sultan Seyyid Said, because he was the one who introduced plantation agriculture with the clove industry. At that point, they needed an influx of slaves. There were slaves being sent out early to the Middle East, to what's now Iraq. There were Zanj being sent to Iraq quite early. In 1200, there was a very famous revolt, the Zanj Revolt of black slaves in Iraq, who drained the marsh land. The revolt was so successful that Arabs in that region decided not to employ massive amounts of slaves because it proved too costly to maintain order over them. So large-scale slavery didn't really picked up on the East African side of things until the French got involved in things with the sugar plantations in Mauritius and the Seychelles, and then the clove industry in Zanzibar. That's in the early 19th century.

B.E.: You mentioned that there is an alternative narrative about the origins of taarab.

K.A.: Yes, absolutely. The official script is one that I have been fighting against for awhile in my work, along with a couple of other scholars. We are of the opinion that taarab often gets overlooked for the way in which it developed on the coast, not only on Zanzibar, on the island, in the Sultan’s palaces, but how taarab emerged just through ordinary interactions among musicians on boats, who came in through these Indian Ocean networks, meeting up with musicians they met on the docks, and sharing musical ideas back and forth. Through those musical interactions, those very unrecorded, undocumented interchanges between people just sharing music and coming up with some interesting sounds together-- that is where I would say taarab also developed on the coast. And there you have, as opposed to the really imposed Middle Eastern sound, you had something else emerging that was very much syncretic from the get go. It didn't have to be sycretized after-the-fact, but was syncretic from the get go, with different musical instruments being contributed to the mix, as well as musical ideas, in terms of really, melody, and form.

B.E.: So this official version about Barghash and musicians from Egypt has gained currency because people so often repeat it. But is there any political significance to these two narratives? Or is it one of just people repeating the story and not questioning it?

K.A.: I think it's that. I think people have just accepted it. It has been repeated so often that people assume that is indeed the start of taarab. What is true is that Zanzibar taarab really was very, very dominant in part because of a particular singer by the name of Siti binti Saad who became wildly famous throughout East Africa and beyond.

She did some recordings in Bombay in the late 20s, and those recordings circulated, so she got some fame outside of East Africa, but within East Africa, she was certainly a big hit in the 1930s. Zanzibar's version of taarab, because it got the official support from the court, did get to get recorded and played. By the way, do you also know the book by Laura Fair? She wrote a book called Pastimes and Politics [Culture, Community, and Identity in Post-Abolition Urban Zanzibar, 1890 –1945: Ohio University Press, 2001] She has a whole chapter on Siti binti Saad. [Editor: Kelly subsequently provided this chapter and it is an excellent essay, indispensable to anyone interested in Siti Binti Saad!]

BE.: Who is Siti binti Saad?

K.A.: Siti binti Saad was a woman of slave ancestry who became a very, very famous taarab singer, whose voice became known outside of Zanzibar, certainly all up and down the East African coast, and beyond, because she was lucky enough to be taken introduced a recordings in Bombay, I think on the HMV label, and became a phenomenon far and wide. So her name became affiliated with taarab in a way that nobody else has since.

B.E.: You write that she became responsible for “Africanizing" the taarab genre.

K.A.: She Africanized it because, although she was one of the first women taken in to sing for the Sultan as one of his court musicians—Sultan Barghash—she didn’t only sing it in Arabic as the Egyptian musicians before her had done. She started singing in Swahili. And she also started singing outside the palace walls. There was actually a rule prohibiting the performance of taarab outside of the palace, but nevertheless it was done, and her house was one of the places where people gathered to listen to taarab and on the spot improvisation of Swahili lyrics, to comment on what ever was happening of importance in the neighborhood or in court, to talk about political matters. One could do that through taarab, and do it in such a way that you camouflage what it is that you were really talking about. [Editor: Laura Fair’s essay details Siti binti Saad’s amazing history of commenting pointedly through music on the Sultan’s law, and later that of the British courts, both terribly unfair to women.]

B.E.: Let's talk about Swahili poetry, obviously an important aspect of taarab music.

K.A.: Swahili poetry extends quite far back in time. We have some very early poetic texts. One of the earliest is called “The Advice of Mwana Kupona,” sometime in the 18th century. This was a poem supposedly written by woman to tell her daughter how she should compose yourself as a future wife, how she treat her husband and have respect for him. We know Swahili poetry goes back several centuries. We don't have a precise dates as to when it first emerged, of course, but one of the names most affiliated with Swahili poetry is that of Lyongo Fumo, who is one of the national heroes of the Swahili coast, who is said to have lived in 1600s. And he is also a credited with being a poet himself, and having sung songs that are still connected today with wedding dances up and down the Swahili coast. So there is a long, rich literary tradition, and very different forms of Swahili poetry exist. You have the utenzi, which are the epics. You have wimbo, which is a word for song, and is a more simple poetic structure of typically six syllables for each half line. The taarab line is typically eight syllables plus eight syllables. So different forms of Swahili poetry have emerged over time, but there is a very rich, very extensive tradition of Swahili poetry. Sometimes, it is in the form of dueling, where people combat each other by composing on the spot, improvisatory poetry, and hurling insults sometimes back and forth at each other. So there is a lot in terms of Swahili poetry that one could go into, of which taarab is only one component.

B.E.: Let's talk about this idea of duality is that you write about. Counter opposing opposites is very popular form of presentation in Swahili culture, isn't it?

K.A.: Sure. Dualism up and down the Swahili coast is something that has been commented on by both local and foreign observers over the centuries. We have a wonderful text, a book dating from the 19th century by a Swahili anthropologist of sorts named Antor Benwengyi Bakari, who wrote down the customs of the Swahili people as he saw them at the time. So we have this wonderful knowledge about how Swahili culture was lived, by local as well as foreign observers. And one thing that has been commented upon, and frequently exemplified by stories and anecdotes of various kinds, is the competitive spirit that we see in so many aspects of life. The political life certainly. We see it in sports. Whereas, say, in the United States, it is typical for each major city to have a single basketball team, a single baseball team, a single football team, in East Africa—and I think it goes even beyond East Africa—you will have at least two teams per town. And everyone in town becomes a diehard fan of one or the other.

This also comes out where I lived in Tanga, on the northern coast of Tanzania, in its religious life. There were mosques that had dualistic relationships with each other, where one would announce that it's Eide, and then the other one would say, no, it's not Eide yet. This certainly comes out in music as well, and so you would have musical groups pitched against each other, singing songs about each other. Often times, ngoma societies—ngoma being the traditional dance forms, with people forming ngoma societies to perform at their weddings and also to serve as self-help groups, to assist people when they're putting on events. In the 1950s, two ngoma societies were especially popular in Tanga. One is called Fanta, and the other is called Kanada Dry, Kanada Dry being a form of ginger ale that had recently been introduced, and Fanta being a form of orange soda that had recently been introduced. So when anything appeared in twos, this made an obvious choice for naming these dualisms that keep reoccurring.

This goes back even into the spatial organization of the villages and towns along the Swahili coast, which were often divided into two halves, that in anthropological terms are called moieties. There would be a spatial division between the town, but it would also take on more symbolic meanings, in terms of newcomers versus old-timers, long-standing Freeborn people versus people of more slave ancestry. These are the ways in which these dualisms could play out. So, in 1950s Tanga, these two sodas had just been introduced, and because there were two of them, the local women's groups decided to take on new names and named themselves after the sodas. So these women's Ngoma groups started putting on performances insulting each other on the basis of their various qualities, the number one being membership in the wrong group. So the Fanta people would sing songs against the Kanada Dry people, and the reverse would be true as well.

B.E.: How did this get expressed in taarab music?

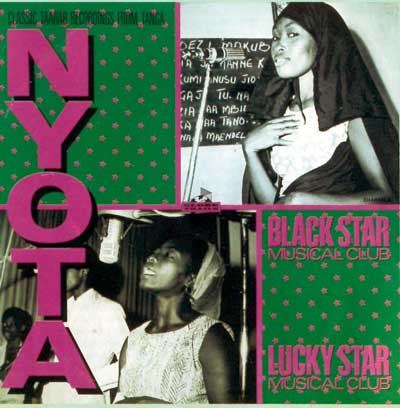

K.A.: In terms of taarab, this came out, as it did with the ngoma groups, with the emergence in the 1970s of two groups called Black Star and Lucky Star Taarab.

Taarab in Tanga has a very different style from that of Zanzibar. Zanzibar taarab, because it started at this very state supported level, had access to more instruments, and develop these large orchestras that today still number of around 30 to 40 people. The two most famous ones today in Zanzibar are Ikhwani Safaa Musical Club, “ The Brotherhood of Purity," and Culture Musical Club. You did not have that phenomenon developing in small towns and villages up along the coast. In Tanga, where I lived, Black Star and Lucky Star Musical Club still had 10 to 20 people in them. The number of musicians was much smaller, but you still had a lot of people singing chorus and back up.

So Black Star emerged in 1970, and they started their tradition of incorporating rhythms from the popular dansi groups. Dansi, now. I am using that term to refer to the popular dance music that was performed and towns primarily. That was pan-ethnic. It wasn't like ngoma, which is usually ethnically based. Often, you would differentiate ngoma on the basis of whether it was a Sukuma ngoma, a Chagga ngoma, a Nyamwezi ngoma, or what have you. Dansi is the urban, jazz music one hears in bars, and that was where Western influence was most often heard, along with Congolese music. The soukous sound in today’s dansi, is just the latest iteration of that.

So, Black Star Musical Club took taarab along a different path by taking the rhythms from the dansi groups of that era, and also taking the more electronic instruments, such as the electric guitar, and electric bass, and ultimately, electric keyboard, and using these to replace the older taarab instruments like the oud, the string double bass, and the harmonium. Black Star Musical Club developed a rivalry with a group that broke off from it called Lucky Star Musical Club, also known as Nyota Njema, which means Lucky Star in Swahili. Throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s, these two bands warred with each other by singing songs about each other, but always through the employ of metaphor. They would have very rarely sung direct insults toward each other. Taarab, the poetic form, is well-known for its use of innuendo and metaphor and multiple layers of meaning to talk about social life, and comment on social life. So Black Star and Lucky Star offers only one of several examples of this competitiveness one finds up and down the Swahili coast.

B.E.: Let’s talk about some of the particular songs that Black Star and Lucky Star singing against one another.

K.A.: One of the first songs that was directed against Lucky Star by Black Star was the song “Mnazi Mkinda,” which means “Young Coconut-Palm.” It was composed by Black Star’s composer Kibwana Said, and sung by their lead singer, Sharmila. The song describes a Young Coconut Palm, the height of which is the important part. It says, "You protect yourself, yet your wealth is destroyed. Your young coconut palm—wily people toy with it. They beat you in cunning, those thieves who desire it.” What it was referring to is the fact that because the coconut palm is still young and short, people can come up very easily and steal the coconuts off of it. This was a very oblique way of talking about a woman whose fruits are easily taken by others, meaning that she's more loose and promiscuous, and the implication was that, Black Star was singing the song directing it towards Lucky Star’s key singer, a woman named Shakila who happens to be rather short. So it was taken as an insult against her.

Now, Lucky Star didn't take this lying down, no, they had to write their response back. And their response was a song called “Kitumbiri,” which means “Monkey.” “Kitumbiri” didn't insult a particular person per se within Black Star, but tried to talk about bigger issues, saying that Black Star shouldn't be jealous about having Lucky Star also on the scene. They shouldn't be greedy and try to take all the taarab success in this one city of Tanga for itself, that there could be more than one taarab group there. So “Kitumbiri,” the song “Monkey,” says, “Even you, monkey, favored monkey, you thought yourself so great, wanting to uproot trees. In fact you are incapable of breaking branches. Goodbye, favored monkey. I think you are confused if you come looking for a fight. If the mighty tree falls on you, you will be injured." And the refrain says, "Favored monkey, you eat at your home and then come to eat against ours." So this was saying: You have your success. You have your fans. There is no need way you have to also try to steal our fans and our success. We can have ours too. Don't be greedy. So that's an example of some of the exchanges that were sent back and forth between these two groups as the rivalry was at its peak in the 1970s and early 1980s.

B.E.: People really got into this, right?

K.A.: Oh, they loved it. In the seventies and eighties, Black Star and Lucky Star, not only in Tanga. It went far beyond that, because they were also recorded by studios not too far away in Mombasa, Kenya, just across the border in Kenya. Their recordings were played on Radio Tanzania, and also in Kenya, on KBC, and the popularity of Black Star and Lucky Star spread throughout what is now Tanzania.

B.E.: So the music is one thing, but the competition creates a sense of drama that people are drawn into as well, right?

K.A.: Oh, yes. As with the sports teams, people become passionate fans of one club or the other. They come to all that club's performances and show their support in the same way as they do at sports events here are elsewhere, routing your team on, and showing your support by coming in high numbers when they perform. In

B.E.: Ultimately, it's not really about anything, is it? It's just personal choice.

K.A.: Well, people have talked about how earlier on, especially, when slavery was recent history, not the older history that it is now, when slave ancestry still very much defined people, groups could be identified as having more slave ancestry attached to them as opposed to more freeborn ancestry. But certainly over the last hundred years, that has faded away, and the now, it is just a matter of personal choice.

B.E.: I find it interesting that in the sleve notes to the Black Star/Lucky Star CD on Globestyle, Werner Graebner does not discuss the rivalry between the groups. He stays away from that altogether. What do you make of that?

K.A.: I don't know why. But you know, the kind of rivalry it was, even though it could occasionally, as in the case of “Young Coconut Palm,” take a nastier tone to it, in fact, most of the time, I don't think it was terribly nasty. It was just good fun. It was just supporting your group, and your family would be more aligned with a certain band than another. But ultimately, all the musicians had started out together. They were all members of Black Star at one time, before they broke off. This is a pattern that would then be repeated further on down the line in 1980s and nineties, when Lucky Star would break apart, and other people break apart from Black Star, to form yet another group. You saw the emergence of Golden Star Taarab and White Star Taarab, and then Babloom Modern Taarab, all through the same process of groups breaking apart on the basis of sometimes personality differences, sometimes disputes over the finances, or what have you. Or just wanting to have the opportunity to have more creative authority. So I don't think there was always a very nasty component to it, although it could take that route.

B.E.: OK, I've got some terms I want you to define for us. Talk about mipasho, mafumbo, and vishindo.

K.A.: Well, when we talk about taarab music, especially talking to people of an older generation, the word that will often come up is mafumbo. Mafumbo means metaphor. That's being able to talk about something by employing metaphor or simile. An example would be the song "Monkey." This is Lucky Star talking about Black Star, but not referring to them by name, referring to them instead as a monkey, trying to employ the attributes of monkeys—monkeys that are always trying to eat anything and everything that they find in a very greedy manner—trying to employ those attributes in reference to Black Star Musical Club. Taarab as very often performed in the context of wedding ceremonies. So love and marriage and sex or key elements of that. So, because of local concepts of etiquette, if you don't want to speak about sexuality openly, you would employ mafumbo to talk about sexuality. You might also employ metaphor to describe your lover in very positive and admiring ways, so mafumbo is a very important word in terms of taarab poetry.

Mipasho is another word that gets used these days, in fact much more than in times past. Mipasho means messages, and sending messages through the text, often by employing mafumbo. So in the case of Black Star and Lucky Star, the monkey is a mafumbo. It's a metaphor, but also there is a message being sent is well saying, "Don't be greedy." So that's the mipasho that is being sent through that song. Mipasho these days oftentimes don't employ mafumbo, which is one of the ways people talk about taarab today being very different from the taarab of a couple of generations ago. They say that mipasho are now right out there, very direct. And it's true. A lot of the lyrics that we have today are more direct. They will be saying, "Don't take my man. You are nothing compared to me. I can beat you any time." Instead of, as in the case of “Monkey,” trying to use a metaphor to and say the same things.

Vishindo is another term that comes up in the context of taarab, and that is challenges, challenging somebody in terms of their moral upstandingness, or their character, or their reputation. Vishindo is a word that gets used describe how taarab lyrics can incite or provoke people, especially women—unfortunately so, because that's a relatively recent development in the history of taarab performance. Before, it used to be very sedate and cordial. There would be these undercurrents certainly of critique being passed back and forth through lyrics, but nevertheless it would be very much under the surface. You wouldn't notice. Even when I started doing my research in the 1980s, and early nineties, it was still very much under the surface. I mean, the first time I ever experienced taarab being employed in this way. I didn't know what had happened. It happened so quickly that I hadn't caught it. All I knew is that I was sitting there with a group of women at a wedding event. There was a song being played. The next thing, a woman was running out of the room in tears, and she had been publicly insulted. I completely missed it. And the only way you could have known was if you understood the lyrics and you also understood the gossip in town, and you knew that the lyrics that had been sung at that particular moment, which were saying something the effect of, "Oh, I know you for what you are. You are a snake. You are coveting my husband. But I am not beguiled. I am fully aware of your character." So the song is saying that and then at that moment, during that song, another woman out of the audience going up to tip the musicians. Ostensibly, it's just to show appreciation for the music. You could be implying that you like the particular vocalist singing, or that you just like that song. But everybody else knows that these things are often very meaning-laden. By choosing to tip at a certain moment in time, or who you look at when you tip, or in what direction your face is pointed when you are tipping, or perhaps a nod of the shoulder, or any sort of indirect gesture with your hand, could send the meanings of that lyric towards somebody else in the audience. So in the case that I first experienced in 1987, this woman had been publicly accused of coveting another woman's husband, and ran from the room. But it was very much under the surface.

B.E.: You talk about "taarab interventions," how in some cases these kinds of the events can actually change the course of people's lives. Can you give an example of that?

K.A.: Sometimes, the use of taarab can actually have long-lasting implications, or consequences that can change people's lives. So for instance, there is a case that I was told love but did not actually witness, of the wife of a taarab singer who heard rumors about her husband's wandering ways, and left him. And when his group was out performing somewhere at a distance—it was an overnight tour, and when he came home, he discovered that his wife had packed up the children and her belongings and left and returned to her familial home. So he was now separated. The town knew about this. It was quite the talk of the town. Life went on, but eventually, the time came when he and his band performed in town, and his wife came to the performance, and during the song that's called “Jamvi la Wageni,” which means “The Visitor’s Mat,” she came up to tip. The song says, "Truly, I believe that a person's character is revealed through their behavior. I never would have believed it. I, your friend, was taken by surprise. In fact he is a visitor's mat on which many have taken rest. He considered me at dupe, the world's biggest fool. He could not get used to being inside. He went seeking out others to sit on. I've had enough of him, my friends. It's not that I hate him. It's that it's not right for one person to remain true and faithful, while the other becomes a visitor's mat on which others sit."

So, here again, we have an example of how a mafumbo is being employed, namely a visitor's mat, which is very common. When you go visit somebody in the Swahili household, they would pull out a special mat for you to sit on. Now in this case, the song employs that to mean something else, an unfaithful and promiscuous spouse. So this wife went up and tipped her husband during this song. He was not singing it. Someone else was singing it. She didn't even look at him. She just went up and tipped and went back to her seat, but because everyone knew the gossip going on, that she had left him, and he was there, it was recognized that she was sending a message to him. And then, soon after that, the negotiations between his family and her family picked up, and a lot of pressure was put on them to reconcile, and in the end they did. And so people say that was a case where, by taking it out of the private domain, and putting it in a very public place, yet in still a very oblique way-- it wasn't a public accusation in the sense that we normally think of, although it was-- it had the impact by resounding throughout and causing yet more talk about their situation, that the elders picked up their pace in trying to negotiate peaceful solution to the problem, and in the end were able in fact to bring about a reconciliation.

B.E.: While we're on the subject of negotiations, you talk about the Tanzanian national identity as being a negotiated phenomenon. It's a complex world with lots of contradictions and paradoxes. Is it possible to connect the kind of story you just hold on a personal level with the broader, more political, realm?

K.A.: Although people think of taarab as being most linked to these kinds of domains, the personal, what I call the politics of the personal, and social relationships, and very intimate communities, people who know what's going on, people who hear the gossip about each other—that’s where taarab is very particularly potent, because that's where meaning can be drawn out from a person's actions as they go up to tip the musicians are not. Nevertheless, despite having a great amount of potency and consequence in those local, intimate settings, still, taarab has managed to have relevance at the national level, not the same relevance, not the same significance, but nevertheless a great deal of significance.

In my work, I talk about how in 1992, Tanzania officially embraced multipartyism. Up until that point, it had been officially a single-party, socialist state. Now, socialism as an economic program had been dispensed with in the 1980s. Liberalization started in the mid-1980s with the second president, Ali Hassan Mwenyi. But socialism still was kind of the official line, and actually it still is. The Constitution has been recently amended, but it still says, "Our goal is to create a socialist society." But in 1992, due to pressure from the World Bank and the IMF, in terms of loan conditionality, it was required that Tanzania adopt a multiparty, democratic system. A lot of money was poured into the country to support the emergence of new political parties that would be able to contest the elections, and oppose the ruling party of Chama cha Mapinduzi (CCM), which means Party of the Revolution. That is still the ruling party of Tanzania today. So this other political party came up into existence, but they have been very weak and very young. The didn't have a whole lot to them, besides having the support of the West, and of international power brokers. CCM very much had an advantage in terms of having inculcated a couple of generations of Tanzanians into believing that CCM was the end-all and be-all of political life in Tanzania. And so they had that advantage. They also have the advantage of control over the major media resources, the radio, and in Zanzibar, they had television. The Tanzanian mainland, surprisingly, did not get television until 1994, two years after multipartyism was introduced.

So, the problem became for the ruling party was how did they convince people that they still deserved support, despite the terrible economic situation that had emerged by the early 1990’s. The eighties were a terrible time for Tanzania in terms of economics. There had been the war with Idi Amin in Uganda where the Tanzanian's went in and single-handedly ousted this guy who was threatening them and many others. The oil crisis had terrible ramifications for Tanzania. There were a whole series of droughts and famines and climatic problems, issues with rainfall, such that Tanzania and much of Africa in the early eighties was suffering terrible economic problems. So the ruling party had to convince people that despite having all these problems they were still the party to lead into the next new phase of multiparty democratic Tanzania. How could they do that?

Well, one of the things they did in 1992 was to create a brand-new cultural troupe called TOT, Tanzania One Theatre. The main attraction for this troupe would be the taarab. This was pretty interesting a development, because although there had been some government support for taarab groups, it was really minimal compared with the government support for, say, ngoma, the traditional dance forms that peppered the country. Ngoma got a lot of government support because it was seen as indigenous, unproblematically African, very authentic. Whereas, taarab was problematic in that it sounded mixed, as it is. It is a syncretic form. It sounds Middle Eastern. It sounds Indian. It sounds African. It's all of that. And therefore it is not so automatically authentic to the newcomer. So the government had not really put a lot of money into taarab.

In Tanga, Lucky Star got a lot of government gigs to perform for visiting dignitaries, and to go and tour and represent Tanzania outside, but not as much as ngoma societies, and not even as much as dansi groups. So TOT, this Tanzania One Theatre, was something quite new in terms of cultural policy, and it burst onto the scene after the government had laid all these rumors in the press about how something new was coming, and it was being hidden, sequestered in the army barracks in Bagamoyo. And this was their new weapon. It was actually called that in the newspapers, “the new weapon of the ruling party." And it turned out it was this taarab group. It wasn't only taarab. They also did ngoma, and dansi, and theatrical performances, but really, the main attraction was taarab. This group merged the sort of large, Zanzibar, orchestral sound with elements of modern taarab from the mainland and places like Tanga. They took the faster beats, such as one that's very popular called chakacha, and also took the lyrics to a new level of directness that had not yet really been seen. Although there were still some songs with mafumbo, there was a lot more directness, and some people even say matusi, which means profanity, very thinly disguised references to sexuality.

B.E.: Tell us about one of their early hits, the one about the high-class a prostitute.

K.A.: The first big hit of TOT was a song called “Ngwinji.” “Ngwinji” means "High-Class Prostitute." The song lyrics say, “A prostitute puts on airs! For what does she put on airs? She also boasts! Of what can she boast? Even if she puts on makeup, who will want her? You prostitute, don't include yourself in the group,” meaning in our group. "She sits and groups, telling people lies that every weekend she spends US dollars. But who will give you money, prostitute. You are not included among those who are loved." So that was one of their songs, very direct, not using metaphor at all except maybe in US dollars being used to represent sort of high-class, foreign status. So to be able to sing about prostitutes in so bold a fashion, by the government troupe, this being their number one, debut song, was considered rather shocking, but exciting at the same time. It really broke new ground in terms of taarab performance, because once the government could do it, then of course others could be equally bald in their references.

Another big hit that the government group did was a song called “TX Mpenzi,” which means "Expatriate Lover." And that was kind of a mafumbo song in that the song is technically about a doctor, trained abroad, so he's an expatriate-trained doctor, which makes him a better doctor supposedly than one trained in Tanzania. It says, "Expatriate lover, my doctor from long ago, he has been removing tumors from my abdomen since long ago. TX, cut me open. Remove my inner illness. I am his only patient. Lady, step aside. I love his injections. They do not hurt my body. When he applies his medicine, my body goes numb. Cut me open, doctor. Cleave me. I await your operation." So this was a metaphor of sorts, but very bold in its meaning.

B.E.: Would this qualify as matusi, or profanity?

K.A.: Yeah, this would be an example of what was making people say that now taarab has entered the realm of matusi. It is no longer mafumbo. It is now matusi.

B.E.: Let's go back to the nationalists for the moment. At that time, you write there were really four kinds of music, taarab, dansi, ngoma, and kwaya. Can you just go through that list and tell me how the nationalists used and viewed each of these genres?

K.A.: The way in which the government of Tanzania approached culture changed very much over time. I would say that in the nationalist period, say 1954 to 1967—that would be the period leading up to independence and immediately after, before the introduction of the Arusha Declaration, which introduced socialism—during that period, the two forms of music which were much more privileged were dansi and ngoma, dansi much more so. Dansi had a lot of influences from not only Congolese music, but Cuban music, and Westerns swing. Foxtrot, cha-cha—these were the beats that were very popular in dansi at the time. This was the music that was danced to by the colonial elite. It also became the music danced to by the African elite, who were aspiring to be their own leaders, so this was a way of establishing cultural parity by saying, "We are your cultural equals. We dance to the same music. We can create same kind of music that you do." So dansi was very much privileged in the nationalist period.

Immediately after independence, however, the first president of Tanzania was Julius Nyerere, and he said, "We don't want to be black Europeans. We want to be ourselves, Tanzanians.” So, suddenly, ngoma became more important than dansi at that point. And ngoma, the traditional dance forms, were sort of a turning of the eye inward to the roots, to try and celebrate that which had been denigrated by the colonial order. So the colonial order thought of ngoma as being incessant drum music that didn't have much meaning, and now finding beauty in that, finding that to be a source of pride, was very important for the new nationalist government in the early sixties.

In 1967, Julius Nyerere introduced socialism into the political and economic system of Tanzania. And his brand of socialism came to be known as Ujamaa. Ujamaa means “familyhood.” He meant it in the way of coming together of people as members of a family, working together, helping each other, and sharing responsibilities for the growth of the nation, the big family, writ large. So in the Socialist period, Ngoma became again the preferred form of music, because it was music of the people. It wasn't associated with an elite class the way that dansi was. And taarab was also associated with an elite class, because it had been associated with the Sultan’s court in Zanzibar. So that was very much upperclass, bourgeois stuff. Even though it really wasn't always. Siti binti Saad was not at all a member of the upperclass. She brought taarab down to every day, ordinary people's music. But nevertheless, it was affiliated with that, with the Sultan’s palace, and certain people's minds, especially the policy makers and the intellectuals of Tanzania during the Socialist period. So ngoma was their preferred form of music, because it represented the music of the masses.

Ngoma, however, had to be altered sometimes to be completely in tune with the Socialist agenda. So when there were ngoma that were either exclusively female or male, if they were going to the representative of the Socialist, gender-equal nation that Tanzania was aspiring to be, then they had to be modified to include both men and women. So you saw the re-choreographing of a lot of ngoma to sort of fit that. They also got re-choreographed to be more Socialist in an aesthetic sense. Oftentimes Ngoma were danced in circles, and this was seen to be somehow backward by some of the people who were in charge of culture in the Ministry of Culture at that time. They thought that it would be better to dance in lines, that that was more modern. Because socialism has a modernist element to it. It sees itself as a rejection of the past, especially in Marxist socialism, and Maoist socialism. Nyerere socialism is less so. He did embrace the past, but he nevertheless did sort of modify it to suit the vision he had for the future. So ngoma were modified to be more Socialist in the eyes of these policy makers.

After the Socialist period ended in the 1980s, now we had economic liberalization occurring. Things started to change, especially with the introduction of political pluralism in 1992. And that’s when taarab had its turn as part of the scene. A fourth kind of music that did have a place in all this was a form of music called kwaya, which is a form of the English word "choir". And it is derived originally from religious music, from choir music found in churches that missionaries had introduced into East Africa. So hymns and choirs were introduced, but they were changed in Tanzania to also be a form of secular, political music. So you have choir music that is not at all religious, but sings about the government, about party leaders, and is very much used especially in Youth Congresses and youth groups. I was an ironic twist, because it really is very much of foreign import, not at all like ngoma with indigenous roots, but nevertheless was included in the national policy of cultural support because it was tweaked to become a form of political praise song.

B.E.: Let's talk about taarab music beyond Tanzania. You write that the trained ear can easily distinguished taarab of Mombasa, Zanzibar, Tanga, or Dar es Salaam. What would the trained ear be listening for in making those distinctions?

K.A.: Regional styles can be distinguished on the basis of their musical attributes. So for instance, Mombasa taarab is thought of as more influenced by Indian music, especially Bollywood, Hindi films, or being more purely Arabic. I'm thinking of Zein l’Abdin who does still adhere to some of the maqamat [classical Arabic modes] when he plays the oud. Maqamat are not really relevant any more in other parts such as Tanga or Dar es Salaam. The oud is still played in Zanzibar, so Zanzibar and Mombasa are the two places where you are still regularly hearing the oud. Mombasa groups tend to be smaller, very small, four or five musicians maximum. They will have a lot of acoustic instruments, the oud as I mentioned, but also sometimes the ney, tabla or dumbek.

B.E.: Taishkota?

K.A.: Taishkota? Nowadays, yes, because of Werner [Graebner]. It had died. Werner resuscitated it. But also sometimes the violin or fidla, which is what they used to use before the taishkota. Linguistically, you can also pick up Mombasa songs because there are certain ways in which they pronounce things in Swahili that are different from places in Tanzania. So the small sound, the more common use of Indian melodies, and sometimes the use of the maqamat would be the ways in which you would distinguish Mombasa taarab. And also, in the Mombasa a region, they would use ngoma rhythms from that area. Mombasa is close to groups such as the Digo and the Giriyama, and other groups that you don't have in Tanzania. So whatever rhythms are unique to those groups, those could find their ways into Mombasa taarab, and that would be different from taarab elsewhere.

On the northern coast of Tanzania, not too far from the Kenyan border, is Tanga, with about 200,000 people in it. As I mentioned, Black Star and Lucky Star are the two groups that most became identified with Tanga. These groups, their sound, was unique in that they were among the first to really incorporate electric guitar, electric bass, and electric keyboard, and they were among the first to start introducing the western drum kit as well. Again, like the Mombasa groups, they are smaller. They tend to be five or six musicians, several vocalists and then backup singers, for total ensemble of 10 to 12 people. But what distinguishes the sound of Tanga is more use of and Ngoma rhythm called chakacha, which you can also find in Mombasa. You can find it anywhere, but Tanga is particularly famous for that. Chakacha is a fast, triple beat. We might consider it a 6/8 beat in western notation. And the nice thing about chakacha, as with any beat felt in six, is that it is divisible by three, and also by two. So you can feel it as 1 2 3, 4 5 6, or else 1 2, 3 4, 5 6. So that you're feeling a strong two downbeat or else a three downbeat.

The Zanzibar sound, because of its supposedly courtly origins, developed these large orchestras. You didn't exclusively have large orchestras in Zanzibar. In fact, Zanzibar used to have quite a number of smaller groups. A lot of those have died out, especially the women's taarab groups. There used to be exclusively women's taarab groups, but they've all pretty much died out now. You have smaller groups called kidumbak, which is taarab that's got a very fast pace to it. It's almost necessary to draw that distinction, because what does get associated first and foremost with Zanzibar is the large orchestra sound. Now you have these modern taarab groups in Zanzibar which are quite small because they are very heavily dependent on the synthesizer and drum machines. So the quintessential Zanzibar sound would be the orchestral sound with the string ensemble of several violins, cello, string double bass. You would also have oud and the ganun. Zanzibar and some few groups in Dar are about the only places on the East African coast where you will find the ganun, which is the trapezoidal zither. You will also have various percussion instruments, bongos, and the dumbek, tambourine, maracas, “timing sticks,” which we call clave in English. So you would have a wide range of acoustic, percussion instruments. Nowadays, the orchestras in Zanzibar also have electric guitar, and sometimes electric bass as well, and electric keyboard.

The songs in Zanzibar are also something that are different in terms of their length. The typical Zanzibar taarab song last 20 minutes. A typical Tanga taarab song lasts eight. So in Zanzibar, the lines are repeated more, and their much longer interludes between verses. That also is sedate giveaway for a Zanzibar song. And then Dar es Salaam is identifiable in being sort of an amalgam of the Zanzibar, large orchestral sound, with the more fast-paced chakacha beat of Tanga. TOT, the Tanzania One Theater group, is perhaps representational of Dar es Salaam, along with Muungano Cultural Group, which actually predates TOT, and was doing a lot of what TOT does, but an earlier point in time. Muungano and TOT became rivals, and still are until today.

B.E.: Let's talk about a few more these songs. How about “Kubwa Lao,” “The Toughest One,” by Babloom Modern Taarab?

K.A.: Another example of a song that employs mipasho, the more direct accusations, even vishindo, these challenges back-and-forth, is a song called "Kubwa Lao.” It really means "The Biggest of Them All" or "The Toughest One." In this song, the composer, a man called Seif Kassim Kisauji, tried to incorporate his knowledge of English, so it's a mix of Swahili and English, let me read you one verse so that you can get a sense of that. “I have already prepared myself for today's event, and I'm sure all challenges end here with me. The floor has cleared. Let the toughest one stand up." And the chorus to the song says, "For calmness, I have no match. And for evil, I am number one." Evil, perhaps, wasn't the best word, but I couldn't find a really good corresponding term for that. It just means for doing that somebody, if I want to. Not that I evil through and through. But if I want to do something against you, I can. This song is a direct challenge to somebody. It's a direct song in a sense of being a mipasho. There are no metaphors all. It's just telling someone: watch out. I'm the toughest one. Don't try to challenge me because you will fail. That song is used a lot, but it became very popular in the mid-1990s, towards the tail end of my field research.

By this time, the decorum of a typical taarab event had started to lift, and started to fragment. By the end of my time in the field, some men I knew were not allowing their wives to go any more to taarab events, because the decorum had fallen aside so much that people were overtly fighting at events. It was not uncommon any more to go to a taarab event and have one woman tipping at the same time another woman is tipping, and they're both tipping for the same reason, so for instance, during this song, they're both saying, "I am number one." "No, I'm number one." "No, I'm number one." "No, I'm number one." And for things to devolve to the point where they would start shoving one another or even tearing at each others' clothes. So that’s a big difference from even the start of my fieldwork and what I understand taarab to have been like in 1970s and 1960s, and certainly earlier, when civility and courteousness and decorum were very much the mode of the day.

B.E.: That's fascinating. And while we’re on that, do you have an update on that situation having just being in Tanzania?

K.A.: I was just in Zanzibar to film a documentary about Ikhwani Safaa Musical Club, which celebrated its 100th anniversary this year, which I'm pretty excited about because very few people know that Africa even has orchestras, much less ones that are as old as that. It fact, that's older than the London Philharmonic, so that's pretty amazing. When they are performing, there's still a lot of decorum, because it's very much considered the more classical, ideal form of taarab. That's not to say that it's not an exciting event. Women still jump up in large numbers. At this 100th anniversary concert, huge swarms of people came up to tip, and tipping multiple times sometimes during the same song. There was a lot of excitement and dancing, although technically you are not really there to dance.

I once made the mistake when I was in the field of saying to my friend, "Come on, let's go and dance." And she said, "No, no, no. I will go tip, but I won't dance." She corrected my Swahili. I was saying kuchesa, to dance. Kutunza is to tip. That is acceptable for Swahili women. You can go and tip. That is decorous. That's civil behavior. The dancing is questionable. You might call your reputation into question that way. So there's still a lot of tipping. I don't know that it has devolved any more. That moment of violent behavior has come and I don't know whether it's gone, but it's certainly been tamed. I think in certain situations, depending on where the taarab is being performed, it might be more likely to occur than in other places. But you still have very much the courteousness of taarab, still even as you have some more riotous behavior breaking out.

B.E.: How about the song “Kumanya Mdigo?” That is the song you used to sing with Babloom Modern Taarab, right?

K.A.: I had trained as classical pianist all throughout college, and I went to the field for my first time in 1987. But when I went to do my doctoral research, it was 1992 to 95. My first year, I was very much the observer. In anthropology and ethnomusicology both, one of our main field techniques is participant observation. So that first year of my three years was more on the observing side. If I participated, it was as an honor on cultural officer. I would go to offense and the given a special, honored chair, and I would sit and watch them, and people would come and ask me for advice on how we do things in the West, and how they could improve their performance practice, and things like that. I didn't really particularly want to be in that role.

But eventually, some of the bands that I was getting to know by attending their rehearsals invited me. One band in particular was a group called the Babloom Modern Taarab. They had been invited to perform on Kenyan television. And it's not that far away. Depending on how long you set the border—the border crossing was always the long part of it—but it could be as short as a three-hour drive from Tanga to Mombasa. So we went to Mombasa for them to perform at KBC, the Kenyan Broadcasting Corporation studios, for a show called Borodani, which means entertainment. It was a show that featured mostly local, East African musicians. We had all this time to kill on the bus, and at the border, going and coming back, and they asked me, "Why are you so interested in our music?" And I mentioned, "Well, you know, in my country, I am also a musician." And they said, "Oh really? What do you play?" And I said, "I play piano." I tried to describe what I piano was, but most people had never seen one. Being the tropical, equatorial place that it is, pianos don't live very well in such conditions. But they had a keyboard with them, a small Casio keyboard. And I said, "It's kind of like that, but many more keys, and bigger."

So they urged me to play for them, and once they discovered my ability, they decided that they would teach me to play with them. And as happened so often in these taarab groups, they break apart, and members leave to join other groups, and to form their own new groups. So part of Babloom split off and ended up forming a different group called Freedom Modern Time. And one of the people that left to form Freedom was the keyboardist. So suddenly a spot was open, and a very much needed a keyboardist, and it just so happened that I was there. So they trained me to be their new keyboardist.

An interesting thing about instrumental music in East Africa is that women are not typically instrumentalists. If they play anything, they play small percussion instruments like the daff, which is a larger, snare drum type thing. Or the tambourine, or clave, which they call timing sticks. So one of the most famous pictures of Siti binti Saad is one where she's holding this daff. So it is certainly not impossible for women to play instruments, but to play something like the keyboard or the guitar or the oud, this is not typically seen. So when I was invited to play, there was a funny story about how they decided to give me a band uniform. My first day to play, I was so honored that I was being incorporated into the band to this degree. I was so honored that they had thought to make me a uniform, and they so proudly presented me with this brand-new shirt. They were all going to wear black pants, and so I wore a black skirt with my new shirt, and impressed upon me how they had made sure to tell the tailor to sew it as a woman's shirt rather than a man's shirt. And yet when I got to the performance, I discovered that all the women were wearing yellow polkadotted dresses, and I was dresses as a classificatory male. I was classified as a male because of my role as instrumentalist, because men are the only ones who normally play instruments. So I became a classificatory male, until they discovered I could sing! Then, I got to wear the uniform of the women. So that was an improvement in my stature, I thought.

So the song, “Kumanya Mdigo,” is one of the songs that I was assigned to sing, and it is unusual in taarab, because it is not in Swahili. I have talked about taarab as being Swahili poetry, but it does not exclusively have to be in Swahili. There are cases where other languages from Tanzania and Kenya are employed, so you have the occasional Giryama taarab song, or Haaya song. And it so happens that this song, “Kumanya Mdigo,” is sung in the language Kidigo. It was written by a Digo member of the group, and it's a very interesting song. I mean, some people would think of it as self-deprecating, because the song says, "Watch out for the Digo. When you see a Digo going about town, don't look down on him. When you see him growth thin, it is due to hardship. Don't do to him things that he doesn't like. Despite his appearance, he is as hard as nails. When he walks, he looks weak because his body is aged. But don't be frightened of him. Don't play around with them. The Digo has no friends. His friend is the millipede. Do not laugh at him or mock him. So if you don't know the Digo, ask, and you will be told. You should be afraid of him. Don't play around with him."

It's sort of pointing out the fact that a lot of Digo are poor. The common occupation for a Digo is to be a fisherman, or a small-scale agriculturalist, a small-scale farmers. Still, he's saying they are tough as rocks. It was composed by a Digo person, and that is the song I became affiliated with singing, even though I am not at all Digo, much less Swahili.

B.E.: You seem to argue that music has played a role in building Tanzania's national identity. How has that worked?

K.A.: In my work I talk about how people employ music, people in all different positions of social life, the wife of the taarab singer having to comment on her husband's unfaithful ways, up to the ruling party trying to harness the potency of taarab, trying to let taarab groups sing songs that would support it. When Tanzania One Theater were performing songs that were very bald in their meaning, more so than any other group had ever attempted before, it seemed rather ironic that they were linked to the government, which had very strict censorship rules. Songs would all have to pass before a censorship board before they could be aired on the radio or recorded by the national recording company at the radio station. It seemed an abuse of power that now that this government troupe should now be absolved of having to go through the same hoops that the other groups had to go through. They could sing whenever they wanted. You would have expected, if you thought about government groups singing for the government, you would expect of them not to be singing about prostitutes or foreign doctors injecting women, but in fact singing about the government, singing the praises of the government, and the ruling party, and the president. And it's true that some of the groups did that, some of the songs did that. But taarab's power is in the realm of social relationships, and people use it to negotiate different things in terms of their social relationships.

Political relationships are certainly one aspect of social relationships, as in songs such as “Mwanya.” A mwanya is a hole, the gap between the two front teeth. It is considered a mark of beauty to have a small gap, and this song called “Mwanya,” that was very popular in Tanga in the mid-1990s, was very popular in the wedding circuit because it talked about small holes that became big holes, and became a metaphor for chaste women who became loose women. It said, "You used to have a beautiful, small gap between your two front teeth. You let down your guard. You got punched in the face. You lost a tooth. Now you have this terrible, gaping whole.” And a whole song went on to describe the consequences of this gaping hole, terrible snoring at night, drooling, on and on. This was a metaphor. It was a rather bald metaphor, but it was a metaphor nevertheless to say that you had something that was valued and something that was considered beautiful and now you lost it, and now you have a terrible life as a result.

So in the wedding circuit, that song came to talk about sexuality, and a woman having lost her good reputation. But other people put different meanings to it. One person told me he thought it meant a person had a good wife, and then he was unfaithful, and he lost his good wife. Or someone else said you had a good job and you are drunk or late all the time, and then you lost your good job. Nevertheless, it's something that you had that was good, that you lost through your own negligence, and as result you are suffering. But ironically, the local ruling party structure in Tanga adopted this as their theme song for the campaign of 1995. This became the song that got performed at each and every political rally, and it would seem again at first glance to be an odd choice. A song that other people knew to be talking about sexuality in very explicit ways to be suddenly representing the ruling party? But because it could be used to mean you had something good, now the ruling party was ridiculing the opposition saying, "You had something good. You had to support of the IMF and the World Bank. You had all this foreign support behind you, and yet what will happen? You will nevertheless lose this election." And, low and behold, they did. You had something good, but it doesn't matter. You lost it.

B. E.: To end, let's go to the big picture. For all Tanzania's problems—the economic failure of socialism, the ineffectual efforts of the culture ministries, and so on—you have to see Tanzania as something of a success story, especially when compared with its neighbors, Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, Congo, even Zimbabwe. Can we make any connections between the music and that success?

K.A.: Some people think that the attempts to institute socialism in Tanzania mark it as one of the failures of African history, but in fact, Tanzania was one of many countries that were suffering in the 1980s, irrespective of political and economic platform. All of Africa suffered in the 80s as a result of poor terms of trade, and the global market for their agricultural products, because of the oil crisis, and yet, despite that, Tanzania gets a bad rap for the socialism, and for the problems that it had. Nevertheless, in terms of culture, and in terms of national unity, one cannot say that Tanzania is a failure. Tanzania is in fact a great success story in that respect, because it managed to unite 120 different ethnic groups into something that is really remarkably strong as a nation, especially when compared with some of its neighbors. One needs only to look at Rwanda and Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Even Kenya has had some of the ethnic problems that Tanzania has been blessed to not have. There have been some problems with the union with Zanzibar, but by in large, Tanzania has not been plagued by ethnic conflict, and some of that can be attributed to the policies of Julius Nyerere, and his attempts to really put culture and the arts at the forefront, and support them in ways, and draw attention, and encourage people to think of themselves as Tanzanians, having this shared culture, having this shared language, and having shared musical tradition. Maybe the best example of that is that when Julius Nyerere died in 1999, just about every kind of music put forth songs honoring his life and his accomplishments. They were called Nyimbo za Maombolezo, “laments songs." Bands across the country, hundreds of bands turned out and composed these songs honoring him. They really came together, and that's one example of how music shows the national unity Tanzania has managed to create.