Louise Meintjes, an Associate Professor of Music and Cultural Anthropology at Duke University, is the principle consultant and voice of Afropop Worldwide’s Hip Deep program “The Zulu Factor.” Her book “Sound of Africa! Making Music Zulu in a South African Studio” (Duke University Press, 2003) is a remarkable urban ethnography of a recording studio in Johannesburg in the early 1990s, a moment when everything was changing in South African music, and politics. Since that time, Louise has kept up with events in South African music, especially among Zulu musicians, whose creative work she continues to study. Here is the complete transcript of the interview Banning Eyre did with Louise in June, 2007, for “The Zulu Factor.”

Note: The color photographs of Zulus (those not from album art) are the superb work of TJ Lemon, whose images are beautifully reproduced in Louise’s book.

Banning Eyre: Let’s start with a little of your background. How did you come to study this subject?

Louise Meintjes: In two ways. Intellectually, I came to study it as an anthropologist and ethnomusicologist working on a dissertation. I started with a master's thesis on Paul Simon's Graceland, and the politics of production that lie behind that album. That prompted me to thinking: What actually happens on the ground? What actually happens in recording studios? How do people make decisions about what a “South African” sound is, or what a “Zulu” sound is? Do they even care about that kind of thing? So from that point, I went to state-of-the-art studios in downtown Johannesburg and met sound engineers, producers, and musicians, and hung around with them. They very kindly and generously let me sit in on the working process. So in addition to doing interviews with various artists—and I include sound engineers and producers in that category—I also went to rehearsals. I went to festivals and gigs. I hung with musicians in their homes. On that basis, I tried to produce an ethnography of a recording studio, and of the production of sounds of “Zuluness,” and “South Africanness” in the early 1990s.

The other part of where my own background matters is that I am a South African, and the music that I ended up focusing on in the early 90s, mbaqanga in particular, and Zulu traditional music more broadly, is music that in the 1970s, in Pretoria, my hometown, I heard on the pavements. I heard it in the backyard. And so it was at the moment I came to study and do research, and subsequently write a book, this music, the music of the 1970s, of my teenage years, was in revival.

B.E: Did you love that music?

L.M: I love that music. But I realized in the 1990s that back in the ‘70s, for me, it was really the music of backyards and suburban sidewalks, when domestic workers were out on their breaks and playing the radio. I realized that I never seriously listened to it then. I heard it, but not in the kind of intense and pleasurable way that I listened to it in the 1990s.

B.E: So in that earlier context, it was music of another world, wasn't it?

L.M: In a sense. Yes. It was part of the environment, but not part of my sonic and political environment at that time in my life. In the white suburbs of South Africa, I did not have the kind of consciousness to say, “This is interesting. This is important.”

B.E: So when you approached it later, were you an ethnomusicologist?

L.M: Yes, I was studying ethnomusicology at the University of Texas in Austin.

B.E: And you are a musician?

L.M: I grew up playing the violin. I played music through my growing years. I studied for a music degree in South Africa, and during that time, in the early 1980s, I only heard one lecture that had anything to do with African music. That was by a musicologist who thought we needed to learn something and went and looked up things about African instruments in a book. But as I became increasingly aware of what was going on around me politically, and as I became increasingly interested in the sociology of music, it took me outside of the classical tradition and led me to an understanding of, and an interest in, the music around me. So in a sense, it was an organic process in which a political consciousness-raising paralleled with a kind of theoretical broadening in my reading in musicology led me into ethnomusicology, and into an ethnography, where I came to meet and hang around with musicians.

B.E: Good. That gives us a little bit of a sense of who you are. Now let's get little historical context on the Zulus. Tell us in brief the history of the Zulu people up to the apartheid period.

L.M: That's of course an absolutely enormous question. Many historians have dealt with this with a lot of sophistication, so I am necessarily giving you a very abbreviated idea here. Essentially, the Zulu are part of the Bantu speaking peoples. The very broad narrative is that the Zulus among the other Bantu speaking people, came down in a southern migration, and landed up in southern Africa. The Zulu nation as we think of it now really grew in stature under King Shaka, who is known as a kind of Zulu Napoleon. He was essentially an imperialist who through military conquest broadened and expanded the Zulu nation across parts of southern Africa. The other component of the history of the Zulu people to take into account here is that, of course, it was in a colonial encounter that what we came to think of as the Zulu nation arose through the last couple of centuries. The Zulu nation came into contact with the various colonialists, and perhaps the most famous—or infamous, in this case—is the British. There were very mighty battles, particularly in the 1870s, against the British Army.

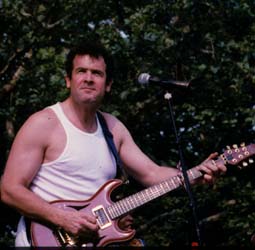

B.E: I always remember that Johnny Clegg song where he sings about one of those battles, the song “Impi.”

L.M: Yes, I think that's a very famous battle, the battle of Isandlwana, where the Zulu actually beat the British. The British overturned the victory within a few days, but that's an absolutely infamous battle that has been reenacted by South Africans and Red Coats, and is commemorated by Zulu nationalists.

B.E: It seems that King Shaka is remembered in different ways, both as a brutal and uncompromising leader, but also as a figure of a kind of romantic pride. Isn't that right?

L.M: Yes. King Shaka is often invoked, and invoked in different contexts. Certainly his name circulates in popular culture, whether it is in poetic forms or music. It’s partly because he developed this reputation as a ferocious militant, but also because he was thought of as someone who was extremely self-possessed, and for whom Zulu identity and Zulu culture were incredibly important. So he was seen as a figure who was royal, self-possessed, and deeply cultural in a sense.

B.E: Also ruthless.

L.M: Absolutely ruthless. But I think one of the reasons why his image has continued to circulate in expressive culture across the globe really comes from those Zulu battles of the later 19th century, in particular from the encounter of the British colonial army with the Zulus. The Battle of Isandlwana is still celebrated today, because [under the leadership of Zulu King Cetshwayo] Zulus with spears and sticks actually beat the Red Coats with their ammunition. It is from that battle in particular that the Zulus earned such a global reputation as being ferocious, cunning, and militant.

B.E: It's interesting that Shaka himself didn't live that long. He was assassinated in 1828. Is it fair to say that the time between the end of Shaka and the ultimate British victory was a very important time for the Zulu, a kind of heyday in which the shape and character of Zululand really came together?

L.M: Yes, I think it was. It was all about consolidating land and consolidating relations with the other groups in southern Africa, as well as with the British. There was a succession of kings that followed Shaka, all of whom had their own characters and strengths. All of them made some sort of contribution to the warrior nation ethos.

B.E: The image of Zulu warrior is central to these people’s pride.

L.M: Absolutely. And that pride is invoked in different ways, often through just naming Shaka. In these praise poems that you hear in some maskanda songs, and in Zulu ngoma dance songs as well, singers often recount lineages in which key figures like Shaka are named.

B.E: That's a little bit like the griots in West Africa, invoking the great names of history and applying them to people today.

L.M: Yes, absolutely. And not only in singing your history to yourself, but in singing your history to the rest of the world. There is a way in which you can identify who you are to the rest of the world by naming people that the rest of the world knows. So to name Shaka or Dingane in particular, is also a way of saying, "I am Zulu.”

B.E: Give us a thumbnail sketch of South Africa’s pop music industry in the final days of apartheid, late 80s and early 90s.

L.M: South Africa has always had a vibrant music industry. If you think that the first recording units arrived in South Africa in about 1912, there is a very long history of record production. By the early 1980s and into the 90s, you had an intense political situation, a part of which was the cultural boycott and economic sanctions against South Africa. So the South African industry had struggled to assert itself internationally, and at the same time it was an industry that grew up with fierce independence, so that in the late 1980s and early 1980s, there were both a lot of small record companies producing a lot of popular musics, as well as a couple of major record companies. Here I would name in particular Gallo (Africa), which held a kind of monopoly over the industry. (Some people would disagree with that viewpoint).

In addition to what was going on in the music industry, of course, the history of radio is very important, and that again is a political history. As part of its ideological apparatus, the South African state relied heavily on radio. Radios were widely available and deeply distributed into rural areas, and broadcasting was a medium over which the South African state had complete control. Part of its ideology of divide-and-rule was to develop radio along linguistic lines, and for that, it also needed product. It needed a lot of local product, and so in a sense, the political needs of the apartheid state created an environment in which the record companies could produce music, and musicians could play music, which if it was appropriate for the radio, they could get an enormous amount of promotion.

B.E: What were the rules? What did it mean to be appropriate for radio?

L.M: There was very heavy censorship. Essentially, in order to get onto the radio, you first had to fit into a linguistically specific category. So you couldn't mix your languages. A lot of censorship was really focused on language. And of course, you couldn't speak politically. So a lot of the music that was considered to be “radio music" was disparaged for being radio music, seemingly apolitical music where the musicians had to make compromises in how they expressed themselves in order to enjoy the promotion of the radio.

B.E: Do you think musicians felt oppressed by that? Did they want to make political statements? And did they find round-about ways to slip political ideas into their songs?

L.M: I think it really varied from musician to musician, and from style to style, and from era to era. The 1960s were different from the 1980s, and ‘90s. But given all of that, I would say that a lot of musicians really struggled with censorship, and were also masters at using poetics. So it's not as though there was absolutely no possibility of being expressive of political positions in how you sang songs. But you really had to do it using your best poetic skills. And also, I would argue, using musical styles to say things for you.

B.E: Can you give an example?

L.M: I think the best example of that is mbaqanga. Mbaqanga was really disparaged as studio-produced radio music—apolitical, commercialized, not part of the South African struggle. But in fact, musicians were drawing on styles, and in particular drawing on diasporic styles that connected them with the ethos of the Soul movement. They were listening very carefully to Atlantic Records at first, later to soul records, disco records, music that tied them to the outside world, and particularly to the ethos of African America. And they didn't do that necessarily in the words that they sang, but they did it in the way that they incorporated aspects of those styles into their own aesthetic. So I would argue that, in fact, what they were doing in part was to make a very local sound, but a local sound which said, "We are urban, we are modern, we are tied into the larger world, and we also celebrate ideas of being black, and we know what's going on in the rest of the world, and we know particularly what's going on around struggles about race and civil rights."

B.E: And you did not just say that with the words, but with the music.

L.M: Right. So, one way you could say it, for example, would be to draw on the organ sound of Jimmy Smith, or to draw on the idea of the "girl group," and to wear Afros and platform shoes when you perform. You could take things into your style from what was going on in the United States, take things into your style that said, "Black is beautiful." That in itself was a radical thing to say in the context of the South African struggle, where the apartheid state was placing its emphasis on ethnicity, on separating people by ethnicity, and on programs of forced removal from urban areas. So to live in an urban, modern world, and to say “I am part of that urban, modern world, and a South African”, was a form of political statement.

B.E: What was Radio Bantu?

L.M: Radio Bantu. Well, all radio was state-owned radio and was divided into different stations, and they were all language based. And so Radio Bantu was the African language section of the state-owned radio corporation. Then within Radio Bantu, there was Radio Zulu, Radio Pedi, etc. etc. etc.

B.E: Why did the state see an advantage in promoting all these language divisions?

L.M: With a policy of divide-and-rule, the idea was to place a premium on ethnic purity and ethnic origins. There was this forced removal policy. The state identified who could belong in which area, and this of course had enormous implications for everybody. If the state identified you as Zulu, that determined your home, irrespective of whether you had grown up in Soweto, or where you had grown up. Your home was KwaZulu. And that would determine where you could work, where you could have land, and what kind of resources were available to you.

The other point I wanted to make is that in order to get promotion on the radio, musicians had to decide what language they were going to sing in. However, these musicians were multi-lingual. What happened with groups as they became popular, such as the Mahotella Queens or Izintombi Zesimanjemanje, is that they would sing songs in more than one language. When a single or an LP was released, they would release two, or three versions of the same record, say, a Zulu version and a Tswana version that could go to different radio stations. But you would never mix African languages on the LP itself.

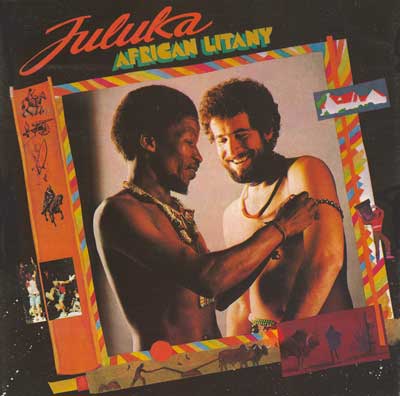

B.E: I guess that's why it was radical when Johnny Clegg and Juluka mixed English and Zulu within this song.

L.M: Yes, I think so. Musicians would sing in English. Izintombi Zesimanjemanje or the Mahotella Queens or the Soul Brothers, all mbaqanga groups, they would sing in English, but they would sing whole songs in English. What a group like Johnny Clegg’s did was to mix languages within the song.

B.E: Can you give us a good definition of mbaqanga?

L.M: Mbaqanga is a studio-produced music, essentially with garage band backing, a close harmony front line that could be men or women, sometimes with a male figure like Mahlathini, who would sing with a deep bass voice, and was known as an "groaner." It was a form of South African Afropop that enjoyed its heyday in the 1970s, and enjoyed a revival in the early 1990s, following the Graceland album.

B.E: What about maskanda?

L.M: Maskanda, you could think of essentially as a singer-songwriter tradition. It comes out of an acoustic, “traditional” context in which musicians play guitars, violins, mouth organs, concertinas, jews harps, but draw upon traditional harmonic progressions from Zulu music, and particularly from the sound of a Zulu bow. It is an improvisational, reflective form of composition, which includes some competitive elements, and some self praise. Different instruments are associated with men and women. Men maskandi generally play guitars, concertinas, and violins. Women maskandi play mouth organs and jews harps.

B.E: I had understood the guitar was pretty much a required presence in a maskanda group. Isn't that right?

L.M: You can be a maskanda musician and not play the guitar. Expanding the singer-songwriter tradition, of course, groups have grown up around different maskandi. It would be unlikely to find a maskanda group, a maskanda band, that did not have the guitar within it. That is right.

B.E: What about isicathamiya?

L.M: Isicathamiya is the Zulu choral tradition that Ladysmith Black Mambazo grew out of. It's a tradition associated historically with migrant labor, as a number of these Zulu styles are. It is a male vocal tradition sung in competitions. There are numerous varieties, but essentially, it is male, choral music.

B.E: And is it specifically Zulu?

L.M: Isicathamiya is in fact Zulu.

B.E: So does that mean that the migrant labor camps were divided ethnically?

L.M: They weren't necessarily segregated by ethnicity, although they were increasingly segregated by ethnicity in the 1980s and early 90s. Lots of South Africans sang. If South Africa is known as anything musically, it is known as a nation of voice. There are thousands and thousands and thousands of choirs of all different kinds, from gospel to isicathamiya in South Africa. Opera is huge in South Africa too. But isicathamiya itself is Zulu-identified choral music.

B.E: Okay, so isicathamiya and maskanda are both Zulu-identified, but mbaqanga is not. I guess this is one of the things that makes mbaqanga special, its lack of an overriding ethnic identity

L.M: Mbaqanga is historically not identified as a Zulu genre. It’s an urban popular genre that grew out of recording studios, where the musicians and the singers were not only Zulus. Some of the key proponents of mbaqanga, like Mahlathini, were Zulus. So mbaqanga became increasingly Zulu identified within the politics of South Africa, and by the early 90s, the time that mbaqanga made a break onto the international scene, it had a much stronger sense of being Zulu music than it did before. In the 1970s, it wouldn't have been spoken about as Zulu music. I think there are two components to this shift. On the one hand, it became more identified as a Zulu music within the domestic context of the late 1980s, early 90s ethnic nationalism. On the other hand, in the context of mbaqanga’s international break, Zuluness becomes an icon of South Africanness.

B.E: Let’s talk about this notion of “Zuluness,” and its emergence as a phenomenon in the period we’re talking about.

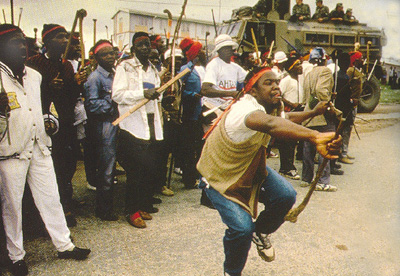

L.M: Okay, essentially there’s a political history of Zuluness leading up to the 1990s. The Inkatha Freedom Party, which was an important Zulu representation at the negotiating tables in the lead-up to the transitional government in 1994, was not always a political party. The Inkatha Freedom Party began essentially as a cultural institution, some say in the 1970s, and was puppeteered into a political party, and a military force by the apartheid state. The reason had to do with the apartheid state's need, from their perspective, to somehow provide a counter option to the popular resistance that was going on in the country. This was resistance that was led by the African National Congress, and the South African Communist Party. So this was kind of popular, class-based resistance. The Inkatha Freedom Party and its violent exploits grew in relationship to the apartheid state's struggle against the African National Congress and the South African Communist Party.

B.E: So this late 80s early 90s surge of Zulu militarism was sort of manipulated and exploited by the apartheid state?

L.M: Yes, it was. That is not to say that Zulu people, in particular some Zulu leaders, had no self interest or had none of their own ideas in developing Zulu ethnic nationalism. But from the point of view of the South African state, Inkatha offered an ideal kind of buffer between the state and the liberation movement.

B.E: And the Zulu, with their military history, were well suited for this, weren't they?

L.M: Well, I think of it as really complicated. It also had to do with which ethnic groups had a strong profile. There were more people whose first language was Zulu than any other language in the country. And it had to do with the political choices that different leaders within the country had made in relation to the South African state's policy of divide-and-rule.

B.E: So the apartheid state “puppeteered” this cultural organization into a political force because that suited their strategy of trying to counter the movement that was coalescing under the ANC and the Communist Party, right?

L.M: I think it's fair enough to say that.

B.E: So, how is this all playing out on the streets around you when you began to do your research in studios in Johannesburg in the early 90s?

L.M: Well, you know, it was a very exciting and chaotic time. Imagine this. Here you have, publicly, these massive negotiations going on among all parties who have some sort of interest in a transitional state. That of course included Zulu and other traditional leaders. So these incredibly difficult negotiations are going on, and beneath that, around that, you have increasing violence, a lot of which tended to be identified as either black-on-black violence, or as ethnic violence. Of course, it was much more complicated than that.

Take raids, for instance: seemingly Inkatha-identified people were going on rampages against seemingly ANC-identified people, who then retaliated, and vice versa. This violence was happening in rural areas and spreading into urban areas, and by the early 1990s, it was happening in and around Johannesburg.

The struggle was also tied up with locations of residence. The informal settlements were associated with African National Congress support. Hostels, that had grown up from migrant labor, were increasingly identified as Zulu, and as places that housed Inkatha dissidents. So what became touted as an “ethnic struggle,” even in the urban areas, was actually also about all sorts of other things: location, class, political affiliation, resources. “Zulu” and “Xhosa” were the easiest markers for a lot of people to hang onto, to identify the terms of the struggle.

B.E: How are all these dramas being reflected in the music that was being recorded in the studios where you did your field work?

L.M: South African music, within the context of South African politics, has been heavily reliant on the producers of the music. Imagine this context. Here you have a largely white-owned record company, or at one stage, fully white-owned record companies, wanting to produce South African music, black South African music, and not knowing anything about it, not knowing where to find musicians, and not having the ears to know what is good and what is bad in terms of local popular aesthetics. As a result, they really needed mediators. Those mediators were the producers and talent scouts. They had say over the sound. They were both the gatekeepers into the industry for musicians, and the mediators for the industry itself, as to who was good and who was bad.

In that context, there were a few producers who became giants. Hamilton Nzimande was one of them. He was one of a group that has become known as "the big five." He began as a record packer. He was never an artist of any standing himself, but he built up this formidable stable of musicians called Isibaya Esikhulu. He had promoters working for him; he had connections into the radio; he ran a very tight ship around his musicians, and produced masses of hits in different kinds of styles.

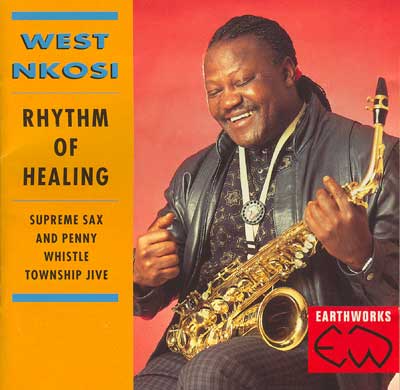

West Nkosi wasn't of the same generation as Hamilton Nzimande. Essentially, he followed him, and overlapped with his career. He came into the industry as an artist in a competing stable to Hamilton Nzimande's. That was the Mavuthela stable under Rupert Bopape, who was one of the other "big five” producers. Being an artist, West was one of the musicians who became a producer and so came to take on a lot of gatekeeping responsibility within the industry, working largely for Gallo Record Company.

B.E: Tell us a little about these two producers’ most successful groups, for West, the Mahotella Queens, and the Makgona Tsohle Band, and for Hamilton, Izintombi Zesimanjemanje.

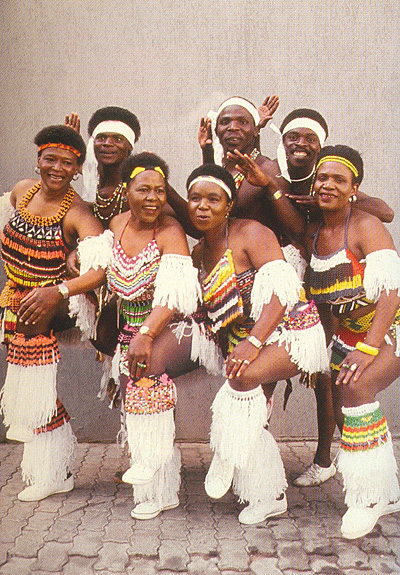

L.M: One of the key groups in Hamilton's stable was Izintombi Zesimanjemanje. That means "the modern girls." They were hugely popular in the 1970s. Mbaqanga subsequently declined as it was kind of eclipsed by disco. But after the Graceland album, and mbaqanga's success on the international market with the Mahotella Queens, there was a moment of revival, and it was at that point that Hamilton Nzimande, urged on by his record company, went back to try to regroup Izintombi Zesimanjemanje. They had been rivals of the Mahotella Queens, and here were the Mahotella Queens touring internationally to great acclaim. It seemed like an ideal moment in which other groups might also be able to make a break into the international market, as well as into a crossover market in South Africa. So at that point, Hamilton Nzimande urged Izintombi Zesimanjemanje— those musicians and singers who were still around—to revive the group. In the end, and I suppose this is part of the irony, Izintombi Zesimanjemanje chose West Nkosi as their final producer. The reason that they made that move, I think, is that they wanted West's ears, and they wanted his international contacts. They saw him as an artist who had toured with Mahotella Queens and who understood what an oversees listener would be looking for, so they swapped Hamilton for West Nkosi as their primary producer in the end.

B.E: And they changed their name.

L.M: The way they explained it was that Izintombi means "young girls." They were now middle-aged women. So they changed it to Isigqi Sesimanje, saying, "We are no longer young girls. But we are still modern." “Manje” means “now.” So they changed their name from The Modern Girls to The Modern Sound, Isigqi Sesimanje. And the other thing that I think the name change gave them was some independence from Hamilton, as they swapped over to West.

B.E: In this context, you describe the recording studio as an intriguing place where all sorts of dramas are playing out. Talk about that.

L.M: Well, when you hear stories of the studio, it's often presented as though ideas go into this black box and things happen, and then ideas come out. I was really interested in what happens in the black box, and so I hung around in the studio with these musicians while they were practicing and producing song after song after song. And I saw that the studio was in fact much like a microcosm of South Africa. On the one hand, it was an intensely creative space. On the other hand it was a place where in order to make good music, you had to work out your social relationships. There were all these power plays enacted according to who had control over the technology, who had final say over how the sound was shaped, who could speak which language, who could understand what language was being spoken. In most cases, you had a white sound engineer, who would probably prefer to be recording rock music in LA, but who had a lot of technical experience recording South African music. You had musicians, who, in the case of mbaqanga or maskanda or ngoma, couldn't necessarily speak good English, although they were multilingual, and couldn't necessarily articulate what they wanted in technical terms. Often, they were working-class and migrant.

In the middle of all that there were the producers, the gatekeepers, who were multilingual, and who in a sense mediated between the musicians and the sound engineer. At this time, producers didn't necessarily have much technological expertise, so they were also really reliant on the white sound engineers. When you have a division of labor, on top of which are mapped issues of race, class and gender, the struggle becomes incredibly interesting. That's what I found in the studio, that in this moment of great promise and great political struggle in South Africa, you had in the studio these very creative people, in a sense, talking about race, and struggling around race, class, and gender, but not using those terms, doing it in the process of producing really beautiful music.

B.E: Can you give us a couple of examples?

L.M: I could give you two stories One is a story about Nogabisela, a Zulu maskandi who plays the guitar. Here he is in the studio, and the sound of the guitar was really important to him. It was part of his identity as a musician, as a Zulu musician. So he would set a sound that he wanted for his guitar on his amp. The sound engineer, of course, wanted control over the sound so that he could get the best sound out of his recording studio. He wanted the control right there at the console. So he would come in and turn down Nogabisela’s settings on his amp so that he could then reproduce the sound in what he would consider a better way at the console. As soon as he turned his back, Nogabisela would turn his settings back up. The sound engineer would say, "What's going on? What's going on?" Then the producer would have to step in and say to Nogabisela in Zulu (which the sound engineer didn’t understand), “Don't worry. I'm looking after your interests here in the control room. Just leave your settings alone." You have those kinds of struggles happening often between the sound engineer and the musicians, where the musicians felt that they were the ones who knew their own music, and the sound engineers felt they were the ones who knew what good sound is in the context of a recording studio.

Another example happened during the Isigqi Sesimanje sessions and had to do with the change from an organ to the marimba sound. One day the musicians came into the studio. They had been practicing with this very florid organ sound. It was the sound of the 1970s. They played an old Korg, which they liked very much because it reminded them of the Hammond sound and the Farfisa sound of the 1970s. They came into the studio ready to play the sound that they had been rehearsing. West Nkosi as the producer said, “No. That sound sounds old. That's no good." He changed it to a Yamaha keyboard that he programmed to the sound of a marimba. In the end, the musicians came to like the change. But at first, they left grumbling because they wanted their own sound, and saw the organ as part of their identifying sound from the 1970s.

The struggle here was over who had final say over the group’s sound. Was it going to be organ, or was it going to be marimba? The musicians wanted organ, because it was their sound from their most popular time. West, I think, changed to marimba because he wanted it to sound more African. One strategy for doing that was to use the sound of an instrument that everybody thinks sounds like a traditional African instrument. In this case, the marimba is not actually a traditional Zulu instrument, but it is certainly an instrument that is associated with southern Africa.

B.E: You put an intriguing emphasis on the musical quality of timbre as a signifier of various things. Why? What does timbre tell us?

L.M: Historically, popular music scholars spent a lot of time focusing on the lyrics, the meaning of the lyrics, and on analyzing song forms and musical styles, when I would argue that a lot of the significance and meaning lies in the sound. I was prompted to focus on timbre partly by being in a recording studio with these people who have phenomenal hearing acuity. I'm thinking particularly of the sound engineers, who are tweaking things, tiny things, which in the end make a huge difference to the feeling of the song. Little timbral changes make a huge difference.

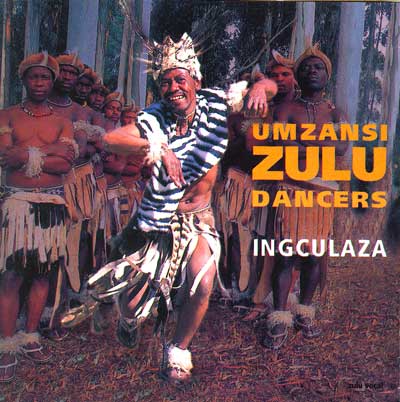

Let me take an example, for instance the way a drum sound was chosen and re-mixed, to give it a more dramatic affect and, for some people, a more Zulu sound. Again, the musicians come into the studio. West Nkosi is behind the console with a white sound engineer, and he wants a nice, strong drum sound. Where does he go to get a nice, strong bass drum sound? He goes to the sound of ngoma drumming. This is Zulu drumming which is associated with very dramatic dancing. The dancers call themselves soldiers. It's a kind of dancing that draws on the martial art of stick fighting historically, and has developed into a competitive recreational form. It is readily associated with the image of the warrior-dancer. The sound of the ngoma drum out on the streets is the sound of a marching bass drum with plastic heads.

West wanted the sound of the ngoma drum, but how did he get to that sound? He had been looking for some kind of music for the international market that would fall between Ladysmith Black Mambazo, an a cappella, choral group that was having great success on the international scene, and the Mahotella Queens, his mbaqanga band. He saw a gap on the market between the two, so he was looking for the sound of a Zulu choral group, but that would be more danceable than Ladysmith Black Mambazo. He hit on this ngoma group, Umzansi Zulu Dance. When he recorded Umzansi, he took the drum sound and made it really prominent in the mix. He then took the sound of the ngoma drum that he had arranged in Umzansi Zulu Dance’s commercial production, and inserted that into Isigqi sesiManje’s mbaqanga mix. So he took a sound he'd already developed and marked as a Zulu sound, and he inserted it into mbaqanga.

West asks the sound engineer to mix that drum sound and make it really tough and ballsy. And when the engineer can't quite get the sound he wants, West says, “Remember the album Ipitombi? That's the sound I want." The sound engineer says to himself, "But that's a sound that's all slap, velum, and air.” It's actually a really bad drum sound. But he understands the feeling that West wants on the drum. That is to say he wants the sound of hand hitting skin. He wants the sound of a “traditional” African drum. He wants the sound of a live performance. And so he takes that idea, that feeling, and then tweaks the drum sound that he has produced electronically to give a feeling of toughness and what he calls “ballsiness.” In the process, nobody has identified that as a Zulu sound. It's not that West or the sound engineer necessarily want a Zulu sound. But they have made a sound available to be retrieved as Zulu, should listeners choose to listen to it that way.

B.E: So "tough" and “ballsy” become code words for Zulu.

L.M: Absolutely. This is code for Zulu, and that in turn comes from two places: the actual sound of drumming on the streets in the ngoma tradition, and an idea of toughness and ferociousness that is circulating internationally about the Zulu. It is particularly ironic that the Ipitombi album, which grew out of a fiercely racist performance context, becomes a kind of intensifying idea of the Zulu on the street.

B.E: The first time the Mahotella Queens recorded in Europe was the Paris Soweto album in about 1990. West Nkosi was again in the role of producer, but this time he seems to have gone for a different sound. I gather one of the sound engineers in South Africa you are working with, John Lindemann, noticed a big difference. Talk about that

L.M: John Lindemann is a veteran sound engineer who worked with West Nkosi a lot. For him, the Paris Soweto album has what he calls a "French mix.” It is too clean, and there's too much space in it. The South African studio aesthetic for a dance music mix in the 1970s and 80s is very different. First of all, the vocals and instruments are really treated as equals. The instruments are mixed very high, right alongside the vocals. And second, there's not a lot of space between the instruments as they play. Many instruments are playing at the same time, so you get this dense texture. The sounds are not located in three-dimensional space as widely as, say, what John Lindemann is calling the "French mix." And third, there's a real stridency in a lot of the South African mixes which has to do with trying to get a really strong, pounding bass. Stridency in the vocals and in the more high pitched instruments is needed to cut through the pounding bass and the dense texture. So it’s all that density, that grittiness, that closeness, that weight, that John Lindemann does not hear in the clean sound of the Paris Soweto album.

B.E: Talk about the relationship between music making and violence in this story.

L.M: I think there are two things to draw out about the relationship between music and violence at this particular moment in South Africa, and around these particular musicians and styles. The first is, in a sense, a pragmatic one. That is, the way that erupting violence, which is spreading in the rural areas and spilling over into the townships and cities, limits venues and revenues. It also shapes who your audience is. So for musicians playing mbaqanga, or other styles like it, there were far fewer places to play. Also, the places became more and more specified as Zulu spaces. Mbaqanga musicians and maskanda musicians increasingly had to rely on playing in Zulu-identified spaces, such as the hostels, and that meant that the revenues were actually very low too.

It also meant that when they were playing, they were constantly in places that could be dangerous. I remember I went to one festival in rural Zululand in 1991, and backstage at one moment they were about ten producers. It was a fabulous show. I think every single producer, or almost every producer had a pistol on his hip. They didn’t use them at that show. But it became the kind of climate in which these musicians were working. Of course, carrying a pistol became part of the machismo too. In addition to the pragmatics of where you could play and who you got to play for, the violence also determined who was listening to you and how they were listening. So you had to make decisions that were creative decisions, but that wound up being political decisions too. What did it mean to sound Zulu? What did it mean to be a Zulu-identified musician? Even though these kinds of questions weren't often directly spoken about in the studio, they were nevertheless present.

B.E: You write intriguingly about how Zulu musicians balanced different versions of Zulu identity, and felt differently about them. Zuluness is both a source of pride and beauty and a “threat.” Talk about that.

L.M: All these musicians—take Jane Dlamini, bandleader of Isigqi sesiManje, for example—are working in the context of huge transitions, within which there is lots of talk about Zuluness. Jane Dlamini feels deeply about who she is, and part of who she is is a Zulu speaker who grew up in rural Zulu land and moved to town to become a professional musician. At the same time, she comes face-to-face too with moments in which people really disparage Zuluness, or are really fearful of Zuluness. Some of the perpetrators of violence in a place like Soweto, where she lives, were people who emerged out of Zulu identified hostels, probably Inkatha militants who had been put there, paid and trained by South African police.

So imagine being in the townships where rampages are happening in the early 1990s, where people come out of the Zulu-identified hostels and kill people in the African National Congress-identified informal settlements. And then there are retaliations. And you are caught in the middle of this. Within this context, the idea of Zulu is at times threatening. Are Zulu's going to come and take over your house? On the one hand, Zuluness becomes associated with fear at times. At other times, it is a celebration, an ideal of beauty. At still other times, it is just who you are in a particular moment. At some other times, it is something you deny. It really depends on the political position that you find yourself in, the social position you find yourself in, and other things, such as the music market. Zuluness is also a commodity, and it is a hot commodity in the early 1990s. In this environment, Zuluness is absolutely up for grabs. It can never be fixed, and is constantly in debate.

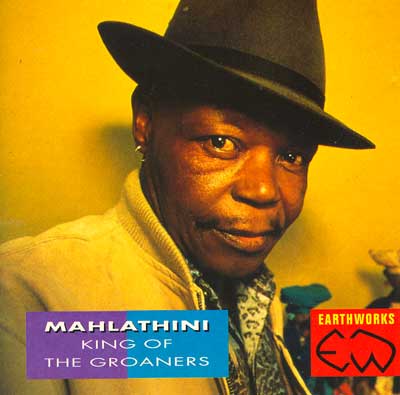

B.E: That’s fascinating. Let’s talk about some specific musical phenomena. Tell us about groaning, and about Mahlathini. How does that fit into this story?

L.M: One of the great sounds of mbaqanga in the 1970s was the “the groaner,” Mahlathini, whose deep, gritty voice made interjections under the women’s close harmony vocals. Mahlathini was a key figure in the internationalization of mbaqanga in the late 1980s and 1990s, because his voice was so distinctive. He himself was Zulu, though his voice was not especially identified as a Zulu voice, but rather as a mbaqanga voice. Mahlathini was greatly admired. Musicians would sometimes try to imitate him, either because they felt it was a way to try to reach a crossover audience that knew Mahlathini, or just because they liked the sound.

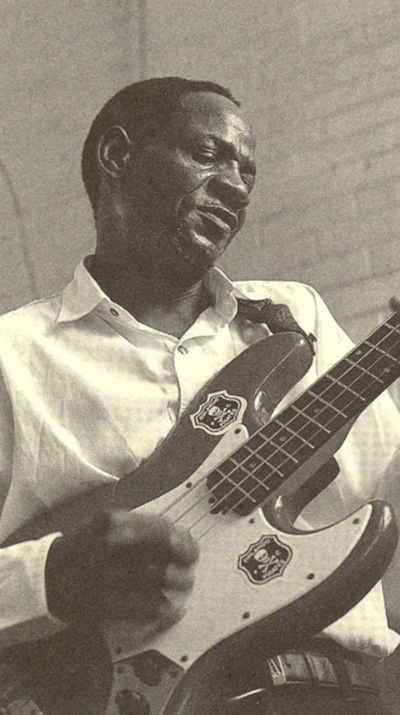

So here we are in the studios in 1991, and Bethwell Bhengu, a good

musician and a bass player who happened also to have a bass voice—was called on by the group to imitate Mahlathini. There were a number of other groaners in the 1970s, but Mahlathini was really the king of groaning. And so Bethwell is called in, but he actually doesn't groan with the kind of quality of Mahlathini. Then West laughs about it, saying, "Ha ha, imitating Mahlathini!" But he also says, "We will leave it in. The market will like it." So this idea of the groan continues to circulate as part of a South African aesthetic.

B.E: Mahlathini’s sound changed quite a bit from the 70s to the 90s, didn't it?

L.M: Yes. I’ll give a bit of history. Mahlathini in the 1990s is celebrated as "the lion of Soweto," a deep groaner whose sound is compared to a wild roaring lion. In fact, his voice changed a lot from the time when he was at the peak of his career. It takes a lot of strain on the vocal chords to sing in that way. By the time he makes it onto the international scene, he is older, and he doesn't have the same kind of range or grit in his voice, so in fact, in the later recordings, if you compare them with the earlier recordings, his groan has domesticated, one might say. In fact, when musicians like Bethwell and Isigqi Sesimanje try to imitate him, they have in their minds the old sound of Mahlathini in the 1970s, even though it is his later voice that circulates internationally.

B.E: Talk briefly about the affect of Paul Simon’s Graceland project on the world of black recording artists in South Africa.

L.M: The Graceland album was a huge event in the world of South African popular music. On the one hand, Graceland opened up an international market for South African music, and that had partly to do with the political moment in which it happened, in the international music industry as well as within South African politics. On the other hand, Graceland created enormous fantasies for South African musicians, and great hope that many more would make it to the international market. For instance, other mbaqanga musicians hoped that because one mbaqanga group had made it onto the international market—that was the Mahotella Queens—many others could also. Or, because one isicathamiya group, Ladysmith black Mambazo, had made it onto the international circuit, that many other isicathamiya groups would. These expectations really stimulated the South African imagination, that at last the world would hear the great diversity of South African music. Of course, it didn't really happen. It happened to a limited extent for a limited number of musicians.

But Graceland did also create revivals on the ground. There was more mbaqanga. There were a lot of isicathamiya choirs who had been singing all this time, who now tried to get recordings going. And musicians did get recorded. Umzansi Zulu Dancers, in effect, because West Nkosi wanted to exploit the opening of the market, started to record as a professional group, and they continue to do so.

There were also other struggles, and I could recount a couple of stories from the perspective of South Africans. I mean, my sense is that the people who fell through the cracks in this were the people who mediated the project for Paul Simon within South Africa. I'm thinking of one independent producer in particular, who I see as a key figure in opening up the field of South African music for Paul Simon. In the end the producer gained very little from the experience, other than what he learned from Roy Halee, Paul Simon’s sound engineer. He had a real interest in learning from Halee. This is a really fabulous person and figure in the South African music industry, Koloi Lebona. He was the guy who, from his account, found the musicians for Paul Simon, and put them together for him, and was in the recording studio listening to get a mix that sounded authoritatively South African, while Paul Simon was recording in Johannesburg. Lebona did not benefit as significantly as I would suggest he should have.

[Editor’s note: Koloi Lebona’s name appears as Sabata Lebona among the South African musicians credited and thanked in the Graceland sleeve notes.]

B.E: That's interesting. I think it was and still is hard for many people to appreciate the great number of artists working in that scene. I remember my own difficulties in trying to sort out the history of the Mahotella Queens. They simply explained that they had taken some time off to have children, and then came back. They didn’t tell me all the ins and outs of the other Mahotella Queens, or about all Mahlathini’s comings and goings, or that Nobesuthu, one of the Queens we know today, actually came from Izintombi Zesimanjemanje. So many complications and details were left out of the story, and then when I began to dig deeper, it became clear that it was far more involved.

L.M: I think the important point is that there was this enormous pool of musicians. They were fabulous musicians, and there was also a lot of interaction among them. There were a lot of fallouts between bands, and breakups, as there always are, a lot of movement from company to company. But the bottom line is there were a lot of musicians who were very active at that time, with fairly fluid movement from group to group.

B.E: What was the significance of the rise of the Soul Brothers?

L.M: The Soul Brothers grew out of Hamilton Nzimande’s stable, alongside Izintombi Zesimanjemanje. In fact, at the beginning, they were largely promoted by backing Izintombi Zesimanjemanje, and then that relationship changed as the Soul Brothers became more popular, and Izintombi Zesimanjemanje's popularity waned. They sort of played off each other, and were integrated onto each other's albums, etc. So when you hear backing male vocals on an album like Best of Izintombi Zesimanjemanje, that is the Soul Brothers. The Soul Brothers epitomized the shift from early mbaqanga into mbaqanga plus soft soul, I would say. And then from that, music moved into a kind of South African version of disco. They were absolutely fabulous musicians, popular across Africa, not just in South Africa, and as popular as the mbaqanga women's groups. Their particular vocal sound, the close harmony, that soft close harmony comes from multiple sources. You can hear some of that soft singing in traditional Zulu music, and other South African sources, but I think they really take it from soul. After the Soul Brothers, it really becomes a staple sound of South African popular music.

B.E: Like mbaqanga, the Soul Brothers were not tied to any particular ethnic identity. So then they make a sort of a link between mbaqanga and disco, and then more contemporary forms like kwaito.

L.M: Absolutely, and then that comes circling back into Zulu traditional music, even in contemporary maskanda.

B.E: Let's talk more about maskanda, and how it has changed with the times.

L.M: Well, historically, the largest catalog of music in South Africa is Zulu music, and one of the genres within that is maskanda. One of the earliest maskandis, found by Hamilton Nzimande, was a man who came to be known as Phuzushukela, or "Sugar Drinker.” His name was John Bhengu, and he was this absolutely fabulous guitarist who in effect came to characterize the sound of maskanda music. He came in playing acoustic, and then was electrified, either by his own choice or on Hamilton Nzimande's direction. The shift is storied in different ways. Out of it developed a massive market for maskanda music, because he was such a popular musician. The sound you hear on the early Zulu acoustic records carries through in the studio productions today. It's a very particular guitar sound, and I would identify a few components. First of all, there's a real percussiveness about it. There's a particular kind of plucking. My sense is—I'm not a guitarist—but there's a lot of fingernail in it.

B.E: Yes, and some of them even use finger picks.

L.M: Yes, to get a really percussive attack on the strings. In addition, a lot of players used really cheap strings, and that fed into the acoustics of a really strident sound, as did playing high up on the neck.

B.E: Sometimes, they're using guitars whose necks are not very straight, and they actually tune the strings lower, and use a capo to bring it up to pitch. That also adds a real buzz to the sound. I noticed that when we were interviewing Shiyani Ngcobo.

L.M: And whatever instrument it is, that buzz is part of the excitement of the sound. You also have to put this in the context that we were talking about earlier of the very dense mix. If you are playing a guitar with a very heavy bass, and the vocals are very close to you in range, and it's all mixed up very tightly, then you have to find ways to get your sound to break out so that people can hear it. A characterization that some of the sound engineers used is that it has to hurt. You have to make the guitar cry. You have to make it stand out in a very busy mix. The musicians would ask for a really strident sound from the engineer, and so that also becomes a characteristic of the maskanda guitar sound.

B.E: You point out that this particular sound becomes the most prominent African guitar style in South Africa.

L.M: Yeah, I think that their way of producing the sound on the instrument, as well as the actual sound of the guitar itself, come to be identified as an “African” way of playing. This is partly because of the broad similarities with other African guitar sounds, a lot of which have a kind of stridency to them. It also has to do with a particular kind of South African sound. If you put just a little bit of that guitar sound into the mix, the ideology, at least as interpreted by West Nkosi, was that the track would be heard as having a South African sound. And I would add to this that Marks Mankwane’s beautiful guitar playing, which was so dearly loved in South Africa and that circulated around the world with the Mahotella Queens, and the Makgona Tshole Band, gave the sound a special value. Because his was such a beautiful sound, people took notice of it.

B.E: Yes, Marks had that way of playing those fast, double-stop melodies high on the neck. That really came to define an aspect of the mbaqanga sound.

L.M: Absolutely, but he does also draw on maskanda. That's a distinctive Marks thing. He includes some of these markers from the maskanda style, for example when he uses those runs that maskanda guitarists start with as a way of identifying their virtuosity, and of identifying the tuning at the beginning of a song. Marks also does that sometimes.

Can I add one more strand, which I think is really important, alongside the guitar strand in maskanda? This is the importance of the concertina and the kind of virtuosity around it. As long as the violin and the guitar have been trade instruments and incorporated into the idea of Zulu traditional music, so has the concertina. It is often played alongside the guitar, but concertina maskandi are also celebrated artists in their own right, and some of them are magnificently virtuosic. One who is really celebrated in the circles of maskandi fans, and who works a lot as a session musician too, is Lahlumlenze. You can hear on his recordings how the concertina can play the same kind of role as guitar. Some of the tunings are altered. It starts out with a kind of virtuosic flurry, which identifies the tuning and identifies the musician, and then goes into a song taking on much of the same form, with self-praise in it, as the guitar maskandi does

B.E: So what about some of the popular maskanda acts these days?

L.M: Maskanda music has remained popular from the time of Phuzushukela on, and of course there are ways in which it has changed. There are lots of guitarists, amateurs and professionals. The maskanda world, with a range of artists playing different instruments but especially the guitar, is a very live world. On top of that, of course, there are popular musicians playing maskanda who are distributed on CD, who are heard on the radio, who appear on South Africa's equivalent of MTV, and who enjoy a celebrated popular musician’s life. Amongst those, in the contemporary moment, would be Phuzekhemisi, Bhekumuzi, and the latest phenomenon, Shwi Nomtekhala. That’s a duo. These maskandi are all loved for different reasons. Phuzekhemisi is a virtuosic guitarist, and also a very interesting lyricist. He first made his splash in a moment of political transition, when he started taking up national political issues, commenting about the transition and about the government, and he has continued to do so. He has a number of songs humorously criticizing the post-apartheid state's slow delivery of services to rural areas, as well as reflecting critically on the past apartheid policy. For example, during the apartheid era, a tax was levied on dog owners in the homelands. In a song called “Ndlwayedwa” Phuzekhemisi wonders whether dogs in the homeland areas will get pensions now that they are old and not working. Another song proved really controversial with the government. Phuzekhemisi sings that because he hasn't seen any changes in the rural areas—no roads, no lights, no running water—he's not going to vote again. At the time of election of local councillors, state officials intervened and asked him to retract his sung statement because otherwise there would be no voter turnout.

B.E: So, would you say that it's the lyrics more than the music that makes a maskanda song popular?

L.M: Well, for a lot of Zulu people who listen closely to maskanda, there are also things about the playing that distinguish artists. So, for instance, Bhekumuzi doesn't have a very decorative playing style. He is especially loved for his poetics, and his very clever lyrics. I would point to the song "Imilanjwana (Children born out of wedlock).” Here he says, "We've got a very big problem in South Africa. The kids are adding another problem on top of the ones we already have. If you're a father or a mother and your kids are getting kids while they themselves are so young, how can you manage?” Bhekumuzi wonders whether the availability of child support grants is the problem. He wonders if the problem in fact comes from the government giving out money. This is confusing young people, who are then not sticking to the right way of doing things.

B.E: Hmm. Tough love, eh? Tell me about Shwi?

L.M: Shwi is an absolute phenomena. He is an absolutely fabulous performer. He is a young guy partnered with Mtekhala, who is his co-singer. Shwi is the guitarist and lead singer. They live in a hostel just outside Johannesburg, and their recordings have become a phenomenon. They have sold more CDs than anybody else in South Africa—that is to say than any kwaito artist, than any of South Africa’s pop artists. Everybody is sort of flabbergasted. It’s partly because they are fabulous performers. I went to a gig at which they performed, and alongside me were hip, 14-year-old African teenagers who were growing up in the suburbs of Johannesburg, who were by no means people who would automatically identify with Zulu traditional music. But here they were being captivated by Shwi and singing along with his lyrics, and holding up their cell phones to capture his image. And alongside them, the usual, very large listenership of maskanda, historically migrant and rural. So it is partly to do with the songs he sings, and the kind of creativity of his lyrics, and it also probably has to do with his combination of kind of soft soul, Soul Brothers backing vocal, as well as with his particular voice. One of the things about the maskanda voice that is really loved is the nasality, and he does it so beautifully. The way the singers move on and off pitch, all these beautiful glides on an off notes are also really appreciated by maskanda listeners.

B.E: That’s great. Let’s touch on traditional Zulu ngoma music before we end. You mentioned this group Umzansi Zulu Dancers, the group West tried to semi-electrify back in the early 90s. I have one of their more recent CD’s here, and it is back to an all vocal and percussion sound. What can you tell us about these guys?

L.M: Umzansi Zulu Dance is both a professional group of singers and dancers, and also part of an active community team in rural KwaZulu-Natal, around Keates Drift, where they live. They are absolutely fabulous dancers and Siyazi Zulu, who is the captain of the team Umzansi Zulu Dance, is also a really great composer. The fathers of guys in this group are the dancers from whom Johnny Clegg learned to dance. This was in the 1970s. But that is an important part of the story. Johnny Clegg continues to support them. He continues to come and dance on occasions down in the community in Keates Drift, in KwaZulu-Natal, and he continues to support these musicians by including them in gigs. That's an important part of how Umzansi Zulu Dance has learned to be a professional group, as well as gather an audience. Of course, that would never happen if they weren't really good. They are absolutely fabulous on the stage, and in their community dances. And Umzansi Zulu Dance’s lyrics are really creative.

From their 1999 album, I'd like to give you an example of how at times they are also really daring. There are ways in which this album is a daring album. It is titled Ingculaza (Gallo, 1999), which means "blood." It is a reference to HIV-AIDS. This community lives in an area that is at the global epicenter of the HIV-AIDS epidemic. There is enormous stigma associated with HIV-AIDS in this area, and in South Africa more generally. And here, Siyazi Zulu composes a song entitled “Ingculaza,” and he titles the CD Ingculaza. Recognizing that HIV-AIDS has to be named and accounted for was an important move.

In the song, Siyazi is addressing the young boys in the group, or youths more generally, and saying, "If you boys don't want to listen, then nobody will remain living. You are told all the time you must use jerseys when you make love." You'll hear the word ijazi in the lyrics. That refers to jerseys, i.e. to condoms. "You are told all the time you must use jerseys when you make love. This AIDS is your business. The younger generation is getting finished. The nation is getting finished." And then there’s a beautiful example of his subtle use of poetics. He says, "You, AIDS, you must go back to where you came from." Why is he addressing AIDS and saying you must go back where you came from? It's his way of poetically getting around the culture of blame, enabling him to name AIDS without casting accusations in any direction.

B.E: I assume this message means a lot coming from him in particular.

L.M: Yes, because he's a staunch traditionalist. In this post-West Nkosi production — as well as on the new album he’s working on right now— he is using a sound that is really more traditional, one that literally focuses on his poetic strength. You have the vocals just as they sing in the community team: a lead and a chorus, a lead singer with a stridency and distortion in his voice, which is considered to be powerful. Vocals are combined with the ngoma drumming, and that’s it.

B.E: Is this song typical? I mean, in its subject matter?

L.M: No. This message is only one of a number. If he were only singing, or only composing these kinds of messages, and the group was only singing things like “Ingculaza,” I think the group would have very little currency. It is because it is placed in relation to lots of other kinds of songs, many of them amusing, poetic, comical, and that are about lots of other things. That's why a song like this can take on a particular kind of significance.

B.E: Talk about Zuluness as a worldwide phenomenon. How has this idea and identity been projected out into the world?

L.M: The idea of Zuluness has been projected out into the world through all aesthetic domains, and all over the world, and I think there are two components to it. On the one hand, there is the idea of the Zulu as wild, cunning, and unpredictable. And you see that picked up in various settings. For instance, one of the elite Hong Kong police units is called the Z Platoon, or the Zulu Platoon. On the other hand, what also gets picked up is this idea of the Zulu as royal, self-possessed, and deeply cultural, and you see that, for instance, in the long tradition in New Orleans where one of the highest prestige Mardi Gras floats is the Zulu float. Another example would be the Universal Zulu Nation, the hip-hop “awareness movement” of Afrika Bambaataa. Zulu pops up in all sorts of places. I saw it in a children's cartoon the other day, where the Zulu Platoon represented do-good outerspace warriors. Sometimes, working-class Texans, white working-class Texans, refer to black people generally as Zulus. The idea of exotic Zulus was also picked up historically, partly because the Zulu were so performative. In Victorian times, for example, Zulu were part of the touring phenomena of “exotic natives”. They were featured at the St Louis exhibition.

B.E: So wrapping up, where is the Zulu identity at today, and where is it going?

L.M: That's a very hard one to answer. I would say that all articulated identities always remain up for grabs. Ideas of Zuluness will continue to circulate globally in all these different forms, and in circulating, they will also keep returning back home. That is to say that people who identify themselves as Zulu both celebrate the international circulation of this idea of Zuluness and they are troubled by it. I think that the power of it—that it is a very dense icon—is also its problem—that is, it is a very singular icon. So if you want to be a Zulu musician, or a Zulu-identified musician on the tourist market, or on the international scene, it is very hard to break out of that very stereotypical image. On the other hand, you can draw on its strength and be creative in different kinds of ways.

B.E: Thanks so much. This has been great, and we look forward to hearing more as you continue your work with Zulu music.