Reviews January 30, 2009

Interview: Ryan Thomas Skinner Part 1

Afropop Worldwide’s program New York’s Mande Diaspora, Part 1: Building Community tells the story of one of America’s most remarkable and musically rich African enclaves. The program relies on interviews and encounters with, and recordings by, a long list of artists from Gambia, Mali and Guinea who live or have lived in the New York area. Links to music and information about those artists can be found at the end of this feature. The program is built around the scholarship of Ryan Thomas Skinner, who studied the New York Mande community between 2000 and 2003, after having done field work in Mali. Banning Eyre conducted a very long interview with Ryan, to be published in two parts. Here is Part 1 of their conversation.

Banning Eyre: For starters, why don't you introduce yourself and tell us how you came to study the Mande community in New York City?

Ryan Skinner: My name is Ryan Skinner. Currently, I’m a Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University in ethnomusicology. In terms of how I came to study the Mande community in New York City, you really have to push back to my undergraduate years, back to Carleton College with Professor Chérif Keïta, himself a native Malian.  He came to the United States via the University of Georgia, and is now a professor in Minnesota. He initiated a cycle of interest that has spiraled out into my academic career, which is to focus on the music of West Africa, and of Mande peoples more specifically. Very early on, with Chérif and his influence as a Malian immigrant now firmly based in the United States, the whole issue of travel—how people travel, how they settle, how they adapt to new spaces—became very important to me. This was something I brought with me as I traveled and came to know Mali, Malian society, and the Bamana language, Mali’s lingua franca.

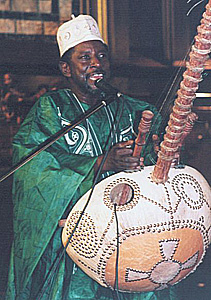

I always had that in my mind, these processes of learning a new place and being a traveler, being a foreigner but coming to know a place in such a way that it becomes more intimate, closer to you. So after 10 years of studying things Malian, the Mande world, the language, the music, the culture, I came to New York City as a graduate student with a new skill set—speaking the language, Bamana, speaking French, having learned to play the kora while in Mali—this idea of travel, this idea of how you adapt to a new place sparked an idea. I wanted to look seriously at how musicians were part of the process of community building. The community, historically speaking, is relatively young, compared with other African communities in New York City. And I'm speaking particularly of Malians and Guineans, but we can perhaps go into the broader Mande community in more depth as we move along.

B.E.: Let’s clarify some basic concepts. Who are the jeliw?

R.S.: To talk about jeliw—or jelis, griots, which is the more current term in European literature—you have to talk about the art form, jeliya, which is not just an art form. It's a way of life. It's a social condition. Jeliya means literally “jeli-ness” the state of being a jeli. It entails forms of musical expression, speech, song, instrumental performance, and dance. Jeliw are clan-based musical artisans, and I say “musical” because even when there is dance, dance is part and parcel of the musical experience. Even when there is speech—for example epic oratory or storytelling—almost always it is accompanied by instrumental performance or song. And what is being communicated in speech, song, instrumental performance, and dance is a cultural heritage that is the responsibility, the hereditary birthright of the jeli.

You are born a jeli. You do not become one. And so this knowledge is passed down from generation to generation. It is an oral tradition. Instruments are learned through the ear. Dances are learned in performance. Songs are learned by listening to your elders, as are stories. Knowledge comes in more esoteric forms sometimes, especially where the knowledge is based on secrets, ideas that are part of a family history. So it is a very deep tradition, but one that is constantly renewing itself.

B.E.: What is the function of jeliya within communities?

R.S.: Jeliya is all a way of bringing people together. There’s a term in Bamana, “ka bèn.” “Bèn” is to come together. The term is used in a variety of contexts, but music in particular literally brings people together. The jeliw are not the only people who play music, but they specialize in this art of bringing people together. Often they are described as being problem solvers, people who resolve conflicts between families, people who preserve the history of a particular family. All this, on a basic level, involves bringing people together, also speaking for people and communities, not just to arbitrate but also to communicate such that ideas are rooted in the sense of history and a sense of tradition even as they project out into an imagined future. These are the tasks of the jeliw. “What do we want our community to become? Well, we want it to be relevant to modern life. At the same time, we don't want to loose track of our past.” The jeli is a person who mediates that move in society.

B.E.: Whenever I have been at a social gathering involving griots, I’ve been struck by the way they make connections among the people in the room, based on people's names, and on knowledge of what has happened in this history going all the way back to the time of the Sunjata epic in the 13th century. The skilled jeli makes those connections in a very fluid way so that time just collapses. It's a long stretch of history, a good 800 years. But it is constantly reinforced through these gatherings, through the art of jeliya, such that you really get a sense of closeness to the past. And from what I have seen, this does help a society cohere. Maybe people are fighting about something now, but history helps them understand where they have common ground.

R.S.: I think that's absolutely right. One way of thinking about this is the idea that even imagined communities are lived as communities. So even as the griots are invoking this epic past, imagining both a real but also highly mythical past and narrative of empire, of great men, great deeds, a great cultural heritage, they are imagining a world and bringing it into a context that seems apparently discrepant, but it's this move of saying, “We can learn from our past. We can learn from these great exploits. Indeed, you are the bearer of that tradition, and I'm going to remind you of it." Then suddenly this mythic world becomes highly relevant, in fact central to the lives of people, to the extent that they respond in kind, often with gifts.

The other part of jeliya is that it is a reciprocal tradition. Jeliw are attached to families, and so they are wards of a family in some ways. But they also have patrons outside of their communities. In servicing these patrons, you have jeliw who may spend much of their adult lives with families in the community, but inevitably the jeliw will travel, whether as apprentices going out to learn and expand on their tradition, or as adults who are seeking to develop a network of patronage, to advance their careers, to establish their names in other places.

B.E.: That concept of going out in traveling has always been part of this art, hasn't it?

R.S.: I think it's helpful to begin with the whole process of apprenticeship. Let's begin with a jelikè, a male jeli, learning to play the kora. A young student will often begin beside his father, or often his uncle if there is tension in the family between the father and son, which is iconically marked by the term fadenya, a tension or rivalry between father and son. So oftentimes, it's an uncle who will take on a young boy. That relationship will proceed through the child's youth and into young adulthood. By that, it generally becomes clear that in order to move beyond the tradition that is ingrained in that particular family space—a repertoire of songs, a particular style, or technique, that is canonically associated with that family—in order to make a name for himself—he needs to go out and learn new things. You need to go to a new place where there is a new style, a different repertoire, a different way of performing. In doing so, you become what they call in Bamana a tògòtigi, literally the owner of proprietor of your name.

Look at the case of Toumani Diabaté's father, Sidiki Diabaté. He comes from coastal Gambia, travels through Senegal along the railways in the 1940s to Kita where he encounters a musical world that is filled not with koras, but with ngonis, balafons, a whole host of other sounds, other sonorities, other techniques that he incorporates into his kora playing style. Being naturally gifted and quite virtuosic, he makes a huge impact of course on that musical world, to the extent that a musical movement is created, the Kayiratòn. This is a whole other history, but the point is that in traveling, new things are engendered. This is a universal truth perhaps, but it is canonically marked in the life of a jeli, and it is very important to move again beyond what's known as the fasiya, the paternal heritage, the cultural patrimony of your family. And you see this from father to son. Take Sidiki, and then look at his son Toumani. Toumani’s wasn’t a move from coastal Gambia to Kita, and then Bamako, like his father’s, but from Bamako to the world. And then Toumani’s own son, Sidiki the younger, shows great promise in much the same way.

B.E.: In your writing, you quote Cherif Keita speaking about how it is not enough for "the Mande person" to simply continue his tradition. He has to add something individual, something of himself. I've gotten mixed reactions to this notion from some of the New York jeliw I've spoken to? For example, Papa Susso did not embrace that, and said that specifically the reason that Cherif would say that, it because he is a Keita, a noble.

He came to the United States via the University of Georgia, and is now a professor in Minnesota. He initiated a cycle of interest that has spiraled out into my academic career, which is to focus on the music of West Africa, and of Mande peoples more specifically. Very early on, with Chérif and his influence as a Malian immigrant now firmly based in the United States, the whole issue of travel—how people travel, how they settle, how they adapt to new spaces—became very important to me. This was something I brought with me as I traveled and came to know Mali, Malian society, and the Bamana language, Mali’s lingua franca.

I always had that in my mind, these processes of learning a new place and being a traveler, being a foreigner but coming to know a place in such a way that it becomes more intimate, closer to you. So after 10 years of studying things Malian, the Mande world, the language, the music, the culture, I came to New York City as a graduate student with a new skill set—speaking the language, Bamana, speaking French, having learned to play the kora while in Mali—this idea of travel, this idea of how you adapt to a new place sparked an idea. I wanted to look seriously at how musicians were part of the process of community building. The community, historically speaking, is relatively young, compared with other African communities in New York City. And I'm speaking particularly of Malians and Guineans, but we can perhaps go into the broader Mande community in more depth as we move along.

B.E.: Let’s clarify some basic concepts. Who are the jeliw?

R.S.: To talk about jeliw—or jelis, griots, which is the more current term in European literature—you have to talk about the art form, jeliya, which is not just an art form. It's a way of life. It's a social condition. Jeliya means literally “jeli-ness” the state of being a jeli. It entails forms of musical expression, speech, song, instrumental performance, and dance. Jeliw are clan-based musical artisans, and I say “musical” because even when there is dance, dance is part and parcel of the musical experience. Even when there is speech—for example epic oratory or storytelling—almost always it is accompanied by instrumental performance or song. And what is being communicated in speech, song, instrumental performance, and dance is a cultural heritage that is the responsibility, the hereditary birthright of the jeli.

You are born a jeli. You do not become one. And so this knowledge is passed down from generation to generation. It is an oral tradition. Instruments are learned through the ear. Dances are learned in performance. Songs are learned by listening to your elders, as are stories. Knowledge comes in more esoteric forms sometimes, especially where the knowledge is based on secrets, ideas that are part of a family history. So it is a very deep tradition, but one that is constantly renewing itself.

B.E.: What is the function of jeliya within communities?

R.S.: Jeliya is all a way of bringing people together. There’s a term in Bamana, “ka bèn.” “Bèn” is to come together. The term is used in a variety of contexts, but music in particular literally brings people together. The jeliw are not the only people who play music, but they specialize in this art of bringing people together. Often they are described as being problem solvers, people who resolve conflicts between families, people who preserve the history of a particular family. All this, on a basic level, involves bringing people together, also speaking for people and communities, not just to arbitrate but also to communicate such that ideas are rooted in the sense of history and a sense of tradition even as they project out into an imagined future. These are the tasks of the jeliw. “What do we want our community to become? Well, we want it to be relevant to modern life. At the same time, we don't want to loose track of our past.” The jeli is a person who mediates that move in society.

B.E.: Whenever I have been at a social gathering involving griots, I’ve been struck by the way they make connections among the people in the room, based on people's names, and on knowledge of what has happened in this history going all the way back to the time of the Sunjata epic in the 13th century. The skilled jeli makes those connections in a very fluid way so that time just collapses. It's a long stretch of history, a good 800 years. But it is constantly reinforced through these gatherings, through the art of jeliya, such that you really get a sense of closeness to the past. And from what I have seen, this does help a society cohere. Maybe people are fighting about something now, but history helps them understand where they have common ground.

R.S.: I think that's absolutely right. One way of thinking about this is the idea that even imagined communities are lived as communities. So even as the griots are invoking this epic past, imagining both a real but also highly mythical past and narrative of empire, of great men, great deeds, a great cultural heritage, they are imagining a world and bringing it into a context that seems apparently discrepant, but it's this move of saying, “We can learn from our past. We can learn from these great exploits. Indeed, you are the bearer of that tradition, and I'm going to remind you of it." Then suddenly this mythic world becomes highly relevant, in fact central to the lives of people, to the extent that they respond in kind, often with gifts.

The other part of jeliya is that it is a reciprocal tradition. Jeliw are attached to families, and so they are wards of a family in some ways. But they also have patrons outside of their communities. In servicing these patrons, you have jeliw who may spend much of their adult lives with families in the community, but inevitably the jeliw will travel, whether as apprentices going out to learn and expand on their tradition, or as adults who are seeking to develop a network of patronage, to advance their careers, to establish their names in other places.

B.E.: That concept of going out in traveling has always been part of this art, hasn't it?

R.S.: I think it's helpful to begin with the whole process of apprenticeship. Let's begin with a jelikè, a male jeli, learning to play the kora. A young student will often begin beside his father, or often his uncle if there is tension in the family between the father and son, which is iconically marked by the term fadenya, a tension or rivalry between father and son. So oftentimes, it's an uncle who will take on a young boy. That relationship will proceed through the child's youth and into young adulthood. By that, it generally becomes clear that in order to move beyond the tradition that is ingrained in that particular family space—a repertoire of songs, a particular style, or technique, that is canonically associated with that family—in order to make a name for himself—he needs to go out and learn new things. You need to go to a new place where there is a new style, a different repertoire, a different way of performing. In doing so, you become what they call in Bamana a tògòtigi, literally the owner of proprietor of your name.

Look at the case of Toumani Diabaté's father, Sidiki Diabaté. He comes from coastal Gambia, travels through Senegal along the railways in the 1940s to Kita where he encounters a musical world that is filled not with koras, but with ngonis, balafons, a whole host of other sounds, other sonorities, other techniques that he incorporates into his kora playing style. Being naturally gifted and quite virtuosic, he makes a huge impact of course on that musical world, to the extent that a musical movement is created, the Kayiratòn. This is a whole other history, but the point is that in traveling, new things are engendered. This is a universal truth perhaps, but it is canonically marked in the life of a jeli, and it is very important to move again beyond what's known as the fasiya, the paternal heritage, the cultural patrimony of your family. And you see this from father to son. Take Sidiki, and then look at his son Toumani. Toumani’s wasn’t a move from coastal Gambia to Kita, and then Bamako, like his father’s, but from Bamako to the world. And then Toumani’s own son, Sidiki the younger, shows great promise in much the same way.

B.E.: In your writing, you quote Cherif Keita speaking about how it is not enough for "the Mande person" to simply continue his tradition. He has to add something individual, something of himself. I've gotten mixed reactions to this notion from some of the New York jeliw I've spoken to? For example, Papa Susso did not embrace that, and said that specifically the reason that Cherif would say that, it because he is a Keita, a noble.  Papa Susso was very clear about the fact that he had no interest in creating fusions or modern music, for example. For him it was all about history and education. How important is this idea of individual expression, or adding. Papa Susso characterized it as more a matter of “personal choice.”

R.S.: Of course it is. I would merely say that Papa Susso has clearly taken jeliya into uncharted territory, and commendably so. He has made a life for himself out of articulating the tradition for American audiences, generally college and university students. This I think can very readily be seen as an individual move to, if not transform the tradition, certainly expand awareness of it. And so I do believe if we know Papa Susso by name, we know that he is one of the most articulate spokespersons for jeliya in North America. So I would argue that he is fully part of that Mande personhood that Chérif Keïta articulates.

I see this in moral and ethical terms. You are raised in the moral space of the family in which you have both the intimacy described by the term badenya—literally the tie between mothers and their children—and then also fasiya, which is cultural patrimony. These are both moral spaces, the intimacy and the tradition. But then there are these ethical impulses. It's a humanist argument, which is to say that at some point in your life, you choose to make a life for yourself. And I think all these musicians and people, not just jeliw, are making lives for themselves. That there are canonical terms for these things only shows that in the Mande psyche, this is a very clear psychosocial orientation, a cultural move if you will.

And again, to talk about Papa Susso, these ethical moves are risky. There is great risk in leaving one's home, whether that's the family household, your home country, however that home is defined. In fact, it's interesting. Faso, meaning "father's home," is also often the way that the nation is rendered. So these spaces are not discontinuous in a modern context. In any case, that's how I see this, as a very humanist move in the lives of Mande people.

B.E.: Interesting. I was struck by Papa Susso’s hesitancy to embrace this concept. Perhaps there was an element of modesty in it, not wanting to draw too much attention to himself as such a crucial character. Too self-promotional. I don't know.

R.S.: There is an ethic of humility, I think, in jeliya. When it comes to self-promotion—the whole idea that I have reinvented tradition in some fundamental and important sense—one must be careful. Not everyone can make such claims. Toumani Diabaté might make such claims. But not everybody is going to be in a position where they feel that that's legitimate, without being shamed. Shame is a powerful consequence that is actively avoided. For many people, shame is associated with social death altogether. So for the jeli to be humble reinforces the idea that, “We are here to uphold tradition. That is our role. not to change it in some radical sense.” And so, looking at these lives, we might see these kinds of innovatory, creative expressions that advance the tradition, as exceptional. but I would say the other part of that cycle is always is re-integrative, bringing innovation full circle. How do we bring what we have created back into that moral space, that paternal heritage, those social mores? That is why music is such a ripe space for this sort of moral-ethical dynamic. Because, by its very nature, it does foster community. It does bring people together. It fosters intimacy not just in a familial sense, but a socio-cultural sense. Music engages with tradition in a dynamic way. This is why I think that these conceptions, of respect for tradition and an impulse toward innovation, are useful in helping us understand the great possibility that is embedded in our musical capacities, and that jeliw are so adept at exploiting, again because jeliya is a centuries old tradition, self-consciously articulated, expressed, and embodied over years of apprenticeship.

B.E.: Let's get a little historical context. Talk about Ahmed Sekou Toure in Guinea, and Modibo Keita in Mali, and how their work on the cultural front had an impact on fortifying Mande or jeli culture in West Africa, but also, by extension, in the world.

R.S.: That's a very, very interesting question. It is connected to the history of jeliya, but it also transcends that and renders it problematic—and I'll explain why. So, under Sékou Touré, Guinea declared its unconditional independence in 1958, two years before other West African nations. This was a surprise. This was shocking. It was expected that the French colonial territories in West Africa would accept a French community that gave greater autonomy to the territories, but also secured a certain economic relationship, which, being colonial, was inherently exploitative. That point can be unpacked much more, but let's leave it there. And so, refusing an inherent exploitation, Guinea pulled out, and France withdrew literally all material and social goods, whether it be bureaucrats or filing cabinets—they were all gone. Sékou Touré had to embark on a program of nation-building that was both radical and urgent… Part of his nation-building project became a cultural policy project to create national ballets, national ensembles and orchestras to literally “perform the nation,” to use a phrase of Kelly Askew’s, so that it (the nation) became a salient reality in the minds of these new citizens, who were no longer subjects of a French empire, but citizens of a Guinean nation. So that comes to the fore very early on in Guinea’s history.

Now Modibo Keita was clearly an active observer of what was going on. He was not yet the head of state, but head of the USRDA, the leading political party in the French Sudan, as Mali was known at that time. He was observing what was happening. The French Sudan became part of the Mali Federation with Senegal in 1959. Modibo Keita then became head of state. A national orchestra was formed in Bamako the same year. Yes, modeled on the experience of Guinea by bringing together, in this case, Sudanese—who would become Malian—musicians, to the exclusion of Senegalese artists. Very interesting dynamics emerged here in which, while the federation was publicly lauded, solidarity between the member states remained weak, to such an extent that the Federation eventually fell apart in August 1960. But that’s another story.

In September 1960, the Guinea National Instrumental Ensemble came to Mali. These ensembles included instruments, traditional instruments, local instruments, indigenous instruments, balafon, kora, ngoni, djembe, dundun—these were all coming together in ways that in some cases had never occurred before. So, while deeply traditional, it was also deeply modern in another way, in terms of how the groups were organized and the songs they produced, which were almost always propaganda songs for the nation, performed on traditional instruments. The Guinean Ensemble toured to Mali in celebration of Mali’s newly declared independence (September 22nd, 1960)—first from France, then as the Federation, then as the Republic of Mali. And the idea comes about to create Mali's own National Instrumental Ensemble.

And so, yes, the dynamic between Guinea and Mali was very important. Modibo Keita’s leadership was very important, but it is important to emphasize here that jeliw were not alone in constituting these groups, especially in the modern orchestras. In fact, in many cases, these modern orchestras may have consciously excluded jeliw in the sense that the goal was to create a modern repertoire, which usually meant Afro-Cuban pieces and European dance band music, with, again, nationalist themes.

B.E.: That was the national orchestra, an electric dance band. But then there was also the more traditional Ensemble Instrumentale.

R.S.: The Ensemble drew heavily from southern Mali, although it brought in musicians from throughout the country as a way of bringing the nation together as a nation, as a coherent space, but it did draw heavily on southern Mali and traditional musicians, who in many cases were jeliw. So jeliya strongly marked that space, instrumentally, but also through the voice, through the jelimusow, the female griots who became prominent voices of the nation within the Ensemble. Mokontafé Sacko, for example, was one of the most prominent female vocalists at that time.

B.E.: That’s interesting. Yacouba Sissoko mentioned that he worked with her. But this must have been an awkward moment for the jeliw, because it was bringing their culture forward, but it was also sort of blurring the line between jeli and artist. Most of the griots I've met speak with great pride about that period and the cultural advances that were made, but back at the time, I wonder if there was some nervousness about it.

R.S.: For example, Nicholas Hopkins writes about a play put on in Kita in 1965, which had the following message for griots. It featured a group of young artists. And you have to look at the category of the “artist” as a very new category at this time. But in this play, you had a young group of artists, a modern orchestra that outperformed a group of traditional jeliw. And the message at the end of the play, the moral if you will, was to say that “You should put down your traditional instruments and pick up the hoe, to work for the nation in a way that is actually meaningful for the nation, to cultivate its fields, to build its economy, an economy that is going to be based on agriculture, that your life world, this culture you have of jeliya, is less useful to us that this nation-building project.” That was a critique of a social hierarchy, a power system, the whole relationship between a noble and a jeli.

Let me briefly describe that hierarchy. Mande society is highly stratified as it's conceived of traditionally, with nobles, hòròn, at the top of that hierarchy, nyamakalaw, artisans who are like the jeliw bound in certain ways to the hòròn—whether as historians preserving the name and historical exploits of families, or as blacksmiths or leatherworkers—and then jòn, who are at the bottom of this hierarchy, captives or slaves.

And so the socialist regime of the USRDA, led by Modibo Keita, was actively trying to diminish the stratification of the society. They were bringing jeliw under the wing of the state, but they were not able to be the patron of all of these musicians. So they were also simultaneously trying to articulate an ideology that opposed this practice of nyamakalaya, and jeliya in particular, which upheld that stratified system. So there was a push-pull, and a lot of that was about consolidating power, about being the patron, about being, in the words of the state the fakòròba, the elder patron of a newly imagined citizenry, the children of the state. The state was conceived, as I said, as the faso, the father's home. It was a family. And in a faso, there is only one patron, and so the state was actively consolidating power in order to make its claims to power legitimate. They were literally inventing this nation-state as quickly and efficiently as they could.

Of course, post-colonial history tells us that it did not work out so well, and yet we are still left with that legacy, and the legacy is that people still do think fondly of that time when there was so much emphasis on bringing people together as a nation. And culture, in a very modern political sense, was at the center of that process. Musicians were being called into the ranks of the government to articulate what was conceived of as not just an important message, but the most important message, to come together as a nation. And clearly, through ensuing decades of authoritarian regimes, of military coups, of political repression, we come to our current era of ostensible democracy, and people are, once again, hopeful. They return back to these early narratives of nation-building, of coming together as a community and saying, yes, culture needs to be at the forefront. The difference is that the state is no longer capable of being that single patron.

B.E.: That's very interesting. I get the feeling that Malians look back with more unambiguous good feeling on the time of Modibo Keita, than perhaps Guineans do on the time of Sekou Toure. Moussa Traore, the dictator who deposed Keita in 1968, kind of absorbed the blow, and is commonly blamed for all the authoritarian horrors. I never heard anybody say a bad word about Modibo Keita.

Papa Susso was very clear about the fact that he had no interest in creating fusions or modern music, for example. For him it was all about history and education. How important is this idea of individual expression, or adding. Papa Susso characterized it as more a matter of “personal choice.”

R.S.: Of course it is. I would merely say that Papa Susso has clearly taken jeliya into uncharted territory, and commendably so. He has made a life for himself out of articulating the tradition for American audiences, generally college and university students. This I think can very readily be seen as an individual move to, if not transform the tradition, certainly expand awareness of it. And so I do believe if we know Papa Susso by name, we know that he is one of the most articulate spokespersons for jeliya in North America. So I would argue that he is fully part of that Mande personhood that Chérif Keïta articulates.

I see this in moral and ethical terms. You are raised in the moral space of the family in which you have both the intimacy described by the term badenya—literally the tie between mothers and their children—and then also fasiya, which is cultural patrimony. These are both moral spaces, the intimacy and the tradition. But then there are these ethical impulses. It's a humanist argument, which is to say that at some point in your life, you choose to make a life for yourself. And I think all these musicians and people, not just jeliw, are making lives for themselves. That there are canonical terms for these things only shows that in the Mande psyche, this is a very clear psychosocial orientation, a cultural move if you will.

And again, to talk about Papa Susso, these ethical moves are risky. There is great risk in leaving one's home, whether that's the family household, your home country, however that home is defined. In fact, it's interesting. Faso, meaning "father's home," is also often the way that the nation is rendered. So these spaces are not discontinuous in a modern context. In any case, that's how I see this, as a very humanist move in the lives of Mande people.

B.E.: Interesting. I was struck by Papa Susso’s hesitancy to embrace this concept. Perhaps there was an element of modesty in it, not wanting to draw too much attention to himself as such a crucial character. Too self-promotional. I don't know.

R.S.: There is an ethic of humility, I think, in jeliya. When it comes to self-promotion—the whole idea that I have reinvented tradition in some fundamental and important sense—one must be careful. Not everyone can make such claims. Toumani Diabaté might make such claims. But not everybody is going to be in a position where they feel that that's legitimate, without being shamed. Shame is a powerful consequence that is actively avoided. For many people, shame is associated with social death altogether. So for the jeli to be humble reinforces the idea that, “We are here to uphold tradition. That is our role. not to change it in some radical sense.” And so, looking at these lives, we might see these kinds of innovatory, creative expressions that advance the tradition, as exceptional. but I would say the other part of that cycle is always is re-integrative, bringing innovation full circle. How do we bring what we have created back into that moral space, that paternal heritage, those social mores? That is why music is such a ripe space for this sort of moral-ethical dynamic. Because, by its very nature, it does foster community. It does bring people together. It fosters intimacy not just in a familial sense, but a socio-cultural sense. Music engages with tradition in a dynamic way. This is why I think that these conceptions, of respect for tradition and an impulse toward innovation, are useful in helping us understand the great possibility that is embedded in our musical capacities, and that jeliw are so adept at exploiting, again because jeliya is a centuries old tradition, self-consciously articulated, expressed, and embodied over years of apprenticeship.

B.E.: Let's get a little historical context. Talk about Ahmed Sekou Toure in Guinea, and Modibo Keita in Mali, and how their work on the cultural front had an impact on fortifying Mande or jeli culture in West Africa, but also, by extension, in the world.

R.S.: That's a very, very interesting question. It is connected to the history of jeliya, but it also transcends that and renders it problematic—and I'll explain why. So, under Sékou Touré, Guinea declared its unconditional independence in 1958, two years before other West African nations. This was a surprise. This was shocking. It was expected that the French colonial territories in West Africa would accept a French community that gave greater autonomy to the territories, but also secured a certain economic relationship, which, being colonial, was inherently exploitative. That point can be unpacked much more, but let's leave it there. And so, refusing an inherent exploitation, Guinea pulled out, and France withdrew literally all material and social goods, whether it be bureaucrats or filing cabinets—they were all gone. Sékou Touré had to embark on a program of nation-building that was both radical and urgent… Part of his nation-building project became a cultural policy project to create national ballets, national ensembles and orchestras to literally “perform the nation,” to use a phrase of Kelly Askew’s, so that it (the nation) became a salient reality in the minds of these new citizens, who were no longer subjects of a French empire, but citizens of a Guinean nation. So that comes to the fore very early on in Guinea’s history.

Now Modibo Keita was clearly an active observer of what was going on. He was not yet the head of state, but head of the USRDA, the leading political party in the French Sudan, as Mali was known at that time. He was observing what was happening. The French Sudan became part of the Mali Federation with Senegal in 1959. Modibo Keita then became head of state. A national orchestra was formed in Bamako the same year. Yes, modeled on the experience of Guinea by bringing together, in this case, Sudanese—who would become Malian—musicians, to the exclusion of Senegalese artists. Very interesting dynamics emerged here in which, while the federation was publicly lauded, solidarity between the member states remained weak, to such an extent that the Federation eventually fell apart in August 1960. But that’s another story.

In September 1960, the Guinea National Instrumental Ensemble came to Mali. These ensembles included instruments, traditional instruments, local instruments, indigenous instruments, balafon, kora, ngoni, djembe, dundun—these were all coming together in ways that in some cases had never occurred before. So, while deeply traditional, it was also deeply modern in another way, in terms of how the groups were organized and the songs they produced, which were almost always propaganda songs for the nation, performed on traditional instruments. The Guinean Ensemble toured to Mali in celebration of Mali’s newly declared independence (September 22nd, 1960)—first from France, then as the Federation, then as the Republic of Mali. And the idea comes about to create Mali's own National Instrumental Ensemble.

And so, yes, the dynamic between Guinea and Mali was very important. Modibo Keita’s leadership was very important, but it is important to emphasize here that jeliw were not alone in constituting these groups, especially in the modern orchestras. In fact, in many cases, these modern orchestras may have consciously excluded jeliw in the sense that the goal was to create a modern repertoire, which usually meant Afro-Cuban pieces and European dance band music, with, again, nationalist themes.

B.E.: That was the national orchestra, an electric dance band. But then there was also the more traditional Ensemble Instrumentale.

R.S.: The Ensemble drew heavily from southern Mali, although it brought in musicians from throughout the country as a way of bringing the nation together as a nation, as a coherent space, but it did draw heavily on southern Mali and traditional musicians, who in many cases were jeliw. So jeliya strongly marked that space, instrumentally, but also through the voice, through the jelimusow, the female griots who became prominent voices of the nation within the Ensemble. Mokontafé Sacko, for example, was one of the most prominent female vocalists at that time.

B.E.: That’s interesting. Yacouba Sissoko mentioned that he worked with her. But this must have been an awkward moment for the jeliw, because it was bringing their culture forward, but it was also sort of blurring the line between jeli and artist. Most of the griots I've met speak with great pride about that period and the cultural advances that were made, but back at the time, I wonder if there was some nervousness about it.

R.S.: For example, Nicholas Hopkins writes about a play put on in Kita in 1965, which had the following message for griots. It featured a group of young artists. And you have to look at the category of the “artist” as a very new category at this time. But in this play, you had a young group of artists, a modern orchestra that outperformed a group of traditional jeliw. And the message at the end of the play, the moral if you will, was to say that “You should put down your traditional instruments and pick up the hoe, to work for the nation in a way that is actually meaningful for the nation, to cultivate its fields, to build its economy, an economy that is going to be based on agriculture, that your life world, this culture you have of jeliya, is less useful to us that this nation-building project.” That was a critique of a social hierarchy, a power system, the whole relationship between a noble and a jeli.

Let me briefly describe that hierarchy. Mande society is highly stratified as it's conceived of traditionally, with nobles, hòròn, at the top of that hierarchy, nyamakalaw, artisans who are like the jeliw bound in certain ways to the hòròn—whether as historians preserving the name and historical exploits of families, or as blacksmiths or leatherworkers—and then jòn, who are at the bottom of this hierarchy, captives or slaves.

And so the socialist regime of the USRDA, led by Modibo Keita, was actively trying to diminish the stratification of the society. They were bringing jeliw under the wing of the state, but they were not able to be the patron of all of these musicians. So they were also simultaneously trying to articulate an ideology that opposed this practice of nyamakalaya, and jeliya in particular, which upheld that stratified system. So there was a push-pull, and a lot of that was about consolidating power, about being the patron, about being, in the words of the state the fakòròba, the elder patron of a newly imagined citizenry, the children of the state. The state was conceived, as I said, as the faso, the father's home. It was a family. And in a faso, there is only one patron, and so the state was actively consolidating power in order to make its claims to power legitimate. They were literally inventing this nation-state as quickly and efficiently as they could.

Of course, post-colonial history tells us that it did not work out so well, and yet we are still left with that legacy, and the legacy is that people still do think fondly of that time when there was so much emphasis on bringing people together as a nation. And culture, in a very modern political sense, was at the center of that process. Musicians were being called into the ranks of the government to articulate what was conceived of as not just an important message, but the most important message, to come together as a nation. And clearly, through ensuing decades of authoritarian regimes, of military coups, of political repression, we come to our current era of ostensible democracy, and people are, once again, hopeful. They return back to these early narratives of nation-building, of coming together as a community and saying, yes, culture needs to be at the forefront. The difference is that the state is no longer capable of being that single patron.

B.E.: That's very interesting. I get the feeling that Malians look back with more unambiguous good feeling on the time of Modibo Keita, than perhaps Guineans do on the time of Sekou Toure. Moussa Traore, the dictator who deposed Keita in 1968, kind of absorbed the blow, and is commonly blamed for all the authoritarian horrors. I never heard anybody say a bad word about Modibo Keita.  R.S.: Well, there’s more to it… Moussa Traore, the military dictator who followed Modibo Keita in 1968, took pains to criticize the authoritarian, oppressive acts that the Keita regime brought upon the populace. And those were very real, including ungoverned militias that terrorized people. So, by the late-60s, people were discontent. But, the fact that Keita was left to die in prison, I think people saw that as very shameful, and that shame patinas over some of the less glamorous and less appealing, and even very horrifying aspects of the latter years of Keita’s regime. Very rarely do you hear people talk about 1964 to 1968.

B.E.: Interesting. It might have all looked very differently had Modiba Keita remained in power. Let's talk about how people identify themselves. I've been getting a sense that many of the people I talked to for the show consider themselves to be first Mande, and only after that either Malian, Gambian, Ivoirian, Guinean, or whatever. The idea is that we've always been Mande, and that the colonial powers came and divided us up. Would you agree with that?

R.S.: Let's talk about the New York community. I think it pushes and pulls both ways. On the one hand, you have a Mande identity that, because of its deep history, is very important to the way people conceive of themselves in relation to their broader community, a vast community across West Africa. You have the Mande heartland which is focused on southern Mali and Northern Guinea, but it has historical diasporas, coastal Senegambia, the Voltaic regions of northern Côte d'Ivoire, and Burkina Faso. And people have a broad understanding of that. At the same time, they aren’t necessarily connected in Mali to the lives of Mandinka Gambians.

Now in a diasporic community like New York where you have Malians, Guineans, Gambians, living in much closer proximity, suddenly this whole idea of Mande-ness is made more salient in a way. It comes forward in a way that it simply doesn't back home. It’s perhaps an ideology, a concept that people understand, but literally, you are much closer and in much greater dialogue with the Kuranko from Sierra Leone, or the Jula from the Ivory Coast. I was walking down Flatbush, and I heard Bambara from two women, followed by a man speaking on his cell phone in Jula—Mande languages. It’s remarkable. And so these people are in very close proximity to each other. Economics, culture, it has all brought them together. They celebrate baptisms together. They celebrate marriages together. They do business together, import-export. The reasons for solidarity are very strong. Now, that said, I did notice in my research that the Guineans and Malians tended to be closer as communities. The Gambian community is older, and be seems to be more, not isolated, but they keep to themselves more than, for example, Mande Ivoirians, Burkinabé, Guineans and Malians. So there are those dynamics, and I was, again, mostly with Ivoirians, Guineans, and Malians, during my research.

B.E.: Great. Now with that background, give us a short history of the development of the Mande community in New York City?

R.S.: Well, the first passing reference I came across about Mande peoples in New York City came from Francois Manchuelle’s book Willing Migrants. The book is about Soninke labor migration, mostly within West Africa, but later on it talks about a diaspora that is established with France, but he does mention that some of those people may have ended up in New York as well. So there is this early presence, perhaps in the 1960s, of a Soninke community. Of course, the Sarakolé, the Soninke, are well-represented in the Malian community here, many of whom are part of the community coming from western Mali.

The next group to talk about is the Murids from Senegal. This is the oldest and most well organized community of West Africans, the Murids being a Sufi Islamic community that is as religiously devoted as they are economically devoted. The two go hand-in-hand. They have established a very lucrative trade network throughout the world in major cities like Paris, like New York, but as far afield as South Asia. This is an extraordinary community of entrepreneurial, religious practitioners. And part of the move for the Murids to the world outside of Senegal came about in the 1970s when they had a series of devastating droughts, and so a local agricultural economy was destroyed.

B.E.: In Senegal ?

R.S.: Well, throughout the region. Then, faced with changes in the economy, and the inability of cities to take on new migrants coming to places like Dakar and Bamako, you look for other opportunities, and at that time, many of those opportunities were emerging in foreign cities. Places like Paris were initially a more obvious choice, but very quickly in the late 70s and 80s, a Murid community is established in New York. This is not the focus of my research, but this is when it was established, and so by the 1980s we have a relatively stable West African community, mostly Senegalese in this case.

B.E.: Are any of the people that arrive in that time through business activities Mande?

R.S.: In my research, I really did not run across people from those communities, again in southern Mali and Côte d'Ivoire, Burkina Faso and Guinea, who had arrived in the 1980s. Everyone I knew arrived in the 90s.

B.E.: But can we say that the activity of that earlier migration at least creates a business context, a doorway through which later Mande emigrants would pass?

R.S.: Absolutely. There is certainly a foundation that is established economically. And it's not just the Murids either. You have Hausa traders. I'm looking specifically at the space of Francophone West Africa, but you have an emergent West African economy that develops in the 80s, and provides a very solid foundation for people from other parts of the region to establish themselves. You have areas that are strongly marked by the West African presence. Take the example of Little Senegal on 116th St, where you have Murid Islamic centers and mosques, you have Senegalese food. But increasingly over the years, you also have Malian restaurants, and you have Ivoirian import-export businesses. They are all now gathering in those places that were founded in a socioeconomic sense by this earlier wave of immigrants.

B.E.: Okay, let's talk about how this specifically Mande community came about.

R.S.: I think the most significant Mande diaspora is from the 60s, that time that Manchuelle is looking at, the postcolonial labor migrations to France. You have a second generation that is firmly established by the late 70s, that is reproducing itself in most of France’s major cities, but Marseille and Paris most strongly. But by the 1980s, immigration law is being actively debated. The concerns about immigration are at the fore of many minds. Radical right political groups are gaining strength. The Front National is gaining influence. And by the late 80s and early 90s, culminating in what is known as the Pasqua Laws. Charles Pascua was the interior minister under François Mitterrand. At that time, there is an anti-immigration sensibility that coincides with the rise of the Front National, and culminates in laws that strongly restrict immigration and crack down on local immigrant communities.

And if we are going to take music, this is at the same time when Salif Keita is coming up with “Nous Pas Bouger.” There is a response. There are movements in the streets, in the suburbs, already in the 90s. And there is a reluctance to go to Paris at that point. There is a turn toward other horizons, and for many, both those who are in the diaspora in Paris and those who are looking to expatriate, to go abroad from Bamako and such places, New York becomes that site.

And for a Mande community that was well established in places like Paris, and elsewhere in France at that time, it becomes a challenge to remain. For many who are lacking official documents—the sans papiers—literally staying in France becomes a kind of impossibility. So many turn to other horizons, and New York at that time, in the early to mid 90s, becomes a point on that horizon, unattainable for some, but sought after by many.

B.E.: Before we get to the musicians, tell me who were the kind of people who would have what it needs to get from either West Africa or from France to New York. Who are these people? Tapani and Yacouba talked about people who sell handicrafts, people who work for the UN. What would your list be?

R.S.: Well, I think that that response is absolutely right. If we are looking precisely at the socio-economic history of the rise of this community, it begins with traders. It begins with people who are selling artisan goods and creating a remittance economy with their hometowns. Then come people who are engaging in broader forms of business, the import-export businesses, and making a decent living for themselves. There are of course foreign dignitaries, the ambassadors, and all of their entourage present at the United Nations, and in Washington, DC. But you know, the community is also evolving. You have students who are coming and studying here increasingly. The language barrier poses problems for French-speaking students. But more and more we are seeing people coming here with the intent to study, exploring professions that go way beyond the business world and the political world. So they too become prominent patrons of jeliw.

I'll give you the example of my mentor and teacher, Chérif Keïta He came to the United States much earlier to study language and literature as a graduate student. But there are people who are following in his footsteps, intellectuals who are coming to American universities and seeing potential there, and making careers for themselves. And they too are now patrons. And so it is a rich and varied world, but certainly this base of patrons had to exist for the artists to really and truly thrive as jeliw, and not simply as musicians—who are like many musicians around the world trying to make a living in a new place, to broaden their horizons, or to get out of a place that was less lucrative, not happening. There is a cultural impulse here, as well as an economic one.

B.E.: How big do you think this community is? If we were to talk about all the Mande people in the five boroughs, how many people would we be talking about?

R.S.: Is very difficult to say. The statistics are so hard to come by. It's several thousand I would say.

B.E.: Papa Susso says there are today 674 Gambians in the Bronx alone, for what that tells us. In any case, we have a situation in the '90s where there's a critical mass of community in New York, so what happens? How do the musicians come here?

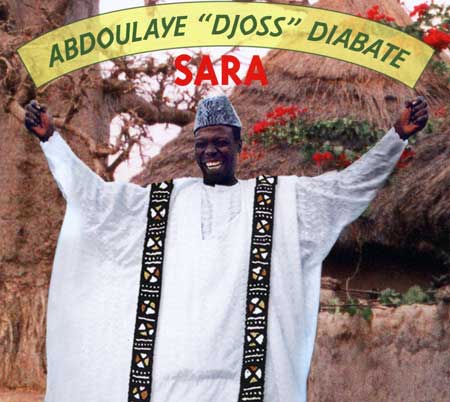

R.S.: The stories are strikingly similar. To immigrate, in a sense, there needs to be a network that is open, and for musicians the key is to be part of a touring group, such as Les Go de Koteba, with which Abdoulaye Diabaté, the singer/guitar player, and Yacouba Sissoko, the kora player, came. This was true for Mamadou Diabaté as well. He came, I believe, with the National Instrumental Ensemble of Mali, as it was formed at the time. Others came with private ensembles and groups and chose to stay. By “private,” I mean groups that operate outside the aegis of the state, for example, tours with prominent musicians. And so these narratives run throughout many peoples’ stories. And then the process of, after having chosen to stay, and to take that step into the United States, the next question is, "How do I make my living? And where do I go?" And with the community that had been established economically in a sense, many jeliw turned to their native communities, and saw a place for their services.

B.E.: Let's talk about some of the individual stories. Let's start with Abdoulaye Diabaté.

R.S.: Well, there’s more to it… Moussa Traore, the military dictator who followed Modibo Keita in 1968, took pains to criticize the authoritarian, oppressive acts that the Keita regime brought upon the populace. And those were very real, including ungoverned militias that terrorized people. So, by the late-60s, people were discontent. But, the fact that Keita was left to die in prison, I think people saw that as very shameful, and that shame patinas over some of the less glamorous and less appealing, and even very horrifying aspects of the latter years of Keita’s regime. Very rarely do you hear people talk about 1964 to 1968.

B.E.: Interesting. It might have all looked very differently had Modiba Keita remained in power. Let's talk about how people identify themselves. I've been getting a sense that many of the people I talked to for the show consider themselves to be first Mande, and only after that either Malian, Gambian, Ivoirian, Guinean, or whatever. The idea is that we've always been Mande, and that the colonial powers came and divided us up. Would you agree with that?

R.S.: Let's talk about the New York community. I think it pushes and pulls both ways. On the one hand, you have a Mande identity that, because of its deep history, is very important to the way people conceive of themselves in relation to their broader community, a vast community across West Africa. You have the Mande heartland which is focused on southern Mali and Northern Guinea, but it has historical diasporas, coastal Senegambia, the Voltaic regions of northern Côte d'Ivoire, and Burkina Faso. And people have a broad understanding of that. At the same time, they aren’t necessarily connected in Mali to the lives of Mandinka Gambians.

Now in a diasporic community like New York where you have Malians, Guineans, Gambians, living in much closer proximity, suddenly this whole idea of Mande-ness is made more salient in a way. It comes forward in a way that it simply doesn't back home. It’s perhaps an ideology, a concept that people understand, but literally, you are much closer and in much greater dialogue with the Kuranko from Sierra Leone, or the Jula from the Ivory Coast. I was walking down Flatbush, and I heard Bambara from two women, followed by a man speaking on his cell phone in Jula—Mande languages. It’s remarkable. And so these people are in very close proximity to each other. Economics, culture, it has all brought them together. They celebrate baptisms together. They celebrate marriages together. They do business together, import-export. The reasons for solidarity are very strong. Now, that said, I did notice in my research that the Guineans and Malians tended to be closer as communities. The Gambian community is older, and be seems to be more, not isolated, but they keep to themselves more than, for example, Mande Ivoirians, Burkinabé, Guineans and Malians. So there are those dynamics, and I was, again, mostly with Ivoirians, Guineans, and Malians, during my research.

B.E.: Great. Now with that background, give us a short history of the development of the Mande community in New York City?

R.S.: Well, the first passing reference I came across about Mande peoples in New York City came from Francois Manchuelle’s book Willing Migrants. The book is about Soninke labor migration, mostly within West Africa, but later on it talks about a diaspora that is established with France, but he does mention that some of those people may have ended up in New York as well. So there is this early presence, perhaps in the 1960s, of a Soninke community. Of course, the Sarakolé, the Soninke, are well-represented in the Malian community here, many of whom are part of the community coming from western Mali.

The next group to talk about is the Murids from Senegal. This is the oldest and most well organized community of West Africans, the Murids being a Sufi Islamic community that is as religiously devoted as they are economically devoted. The two go hand-in-hand. They have established a very lucrative trade network throughout the world in major cities like Paris, like New York, but as far afield as South Asia. This is an extraordinary community of entrepreneurial, religious practitioners. And part of the move for the Murids to the world outside of Senegal came about in the 1970s when they had a series of devastating droughts, and so a local agricultural economy was destroyed.

B.E.: In Senegal ?

R.S.: Well, throughout the region. Then, faced with changes in the economy, and the inability of cities to take on new migrants coming to places like Dakar and Bamako, you look for other opportunities, and at that time, many of those opportunities were emerging in foreign cities. Places like Paris were initially a more obvious choice, but very quickly in the late 70s and 80s, a Murid community is established in New York. This is not the focus of my research, but this is when it was established, and so by the 1980s we have a relatively stable West African community, mostly Senegalese in this case.

B.E.: Are any of the people that arrive in that time through business activities Mande?

R.S.: In my research, I really did not run across people from those communities, again in southern Mali and Côte d'Ivoire, Burkina Faso and Guinea, who had arrived in the 1980s. Everyone I knew arrived in the 90s.

B.E.: But can we say that the activity of that earlier migration at least creates a business context, a doorway through which later Mande emigrants would pass?

R.S.: Absolutely. There is certainly a foundation that is established economically. And it's not just the Murids either. You have Hausa traders. I'm looking specifically at the space of Francophone West Africa, but you have an emergent West African economy that develops in the 80s, and provides a very solid foundation for people from other parts of the region to establish themselves. You have areas that are strongly marked by the West African presence. Take the example of Little Senegal on 116th St, where you have Murid Islamic centers and mosques, you have Senegalese food. But increasingly over the years, you also have Malian restaurants, and you have Ivoirian import-export businesses. They are all now gathering in those places that were founded in a socioeconomic sense by this earlier wave of immigrants.

B.E.: Okay, let's talk about how this specifically Mande community came about.

R.S.: I think the most significant Mande diaspora is from the 60s, that time that Manchuelle is looking at, the postcolonial labor migrations to France. You have a second generation that is firmly established by the late 70s, that is reproducing itself in most of France’s major cities, but Marseille and Paris most strongly. But by the 1980s, immigration law is being actively debated. The concerns about immigration are at the fore of many minds. Radical right political groups are gaining strength. The Front National is gaining influence. And by the late 80s and early 90s, culminating in what is known as the Pasqua Laws. Charles Pascua was the interior minister under François Mitterrand. At that time, there is an anti-immigration sensibility that coincides with the rise of the Front National, and culminates in laws that strongly restrict immigration and crack down on local immigrant communities.

And if we are going to take music, this is at the same time when Salif Keita is coming up with “Nous Pas Bouger.” There is a response. There are movements in the streets, in the suburbs, already in the 90s. And there is a reluctance to go to Paris at that point. There is a turn toward other horizons, and for many, both those who are in the diaspora in Paris and those who are looking to expatriate, to go abroad from Bamako and such places, New York becomes that site.

And for a Mande community that was well established in places like Paris, and elsewhere in France at that time, it becomes a challenge to remain. For many who are lacking official documents—the sans papiers—literally staying in France becomes a kind of impossibility. So many turn to other horizons, and New York at that time, in the early to mid 90s, becomes a point on that horizon, unattainable for some, but sought after by many.

B.E.: Before we get to the musicians, tell me who were the kind of people who would have what it needs to get from either West Africa or from France to New York. Who are these people? Tapani and Yacouba talked about people who sell handicrafts, people who work for the UN. What would your list be?

R.S.: Well, I think that that response is absolutely right. If we are looking precisely at the socio-economic history of the rise of this community, it begins with traders. It begins with people who are selling artisan goods and creating a remittance economy with their hometowns. Then come people who are engaging in broader forms of business, the import-export businesses, and making a decent living for themselves. There are of course foreign dignitaries, the ambassadors, and all of their entourage present at the United Nations, and in Washington, DC. But you know, the community is also evolving. You have students who are coming and studying here increasingly. The language barrier poses problems for French-speaking students. But more and more we are seeing people coming here with the intent to study, exploring professions that go way beyond the business world and the political world. So they too become prominent patrons of jeliw.

I'll give you the example of my mentor and teacher, Chérif Keïta He came to the United States much earlier to study language and literature as a graduate student. But there are people who are following in his footsteps, intellectuals who are coming to American universities and seeing potential there, and making careers for themselves. And they too are now patrons. And so it is a rich and varied world, but certainly this base of patrons had to exist for the artists to really and truly thrive as jeliw, and not simply as musicians—who are like many musicians around the world trying to make a living in a new place, to broaden their horizons, or to get out of a place that was less lucrative, not happening. There is a cultural impulse here, as well as an economic one.

B.E.: How big do you think this community is? If we were to talk about all the Mande people in the five boroughs, how many people would we be talking about?

R.S.: Is very difficult to say. The statistics are so hard to come by. It's several thousand I would say.

B.E.: Papa Susso says there are today 674 Gambians in the Bronx alone, for what that tells us. In any case, we have a situation in the '90s where there's a critical mass of community in New York, so what happens? How do the musicians come here?

R.S.: The stories are strikingly similar. To immigrate, in a sense, there needs to be a network that is open, and for musicians the key is to be part of a touring group, such as Les Go de Koteba, with which Abdoulaye Diabaté, the singer/guitar player, and Yacouba Sissoko, the kora player, came. This was true for Mamadou Diabaté as well. He came, I believe, with the National Instrumental Ensemble of Mali, as it was formed at the time. Others came with private ensembles and groups and chose to stay. By “private,” I mean groups that operate outside the aegis of the state, for example, tours with prominent musicians. And so these narratives run throughout many peoples’ stories. And then the process of, after having chosen to stay, and to take that step into the United States, the next question is, "How do I make my living? And where do I go?" And with the community that had been established economically in a sense, many jeliw turned to their native communities, and saw a place for their services.

B.E.: Let's talk about some of the individual stories. Let's start with Abdoulaye Diabaté.

R.S.: Abdoulaye Diabaté is a great place to start because he has a travel story that begins earlier in some ways, and I think it's important to follow his story. He is, of course, a jeli, so this is part of his cultural patrimony. But as a young man, he takes part in a very lively orchestral, popular music scene in Bamako. This is not a jeli tradition; it's an urban music tradition, and he is very much a part of that. He spent some time in Bamako. He spent some time in Koutiala, in southern Mali, playing music. There comes a point in Mali’s geo-political history where things are deteriorating in the 1970s. It's not just Abdoulaye. It's a mass of musicians. This is Moussa Traoré. There are droughts. Politics are repressive. Resources are scarce. Abdoulaye leaves. He goes to Abidjan, and in Abidjan, under the more liberal politics of Houphouet Boigny, you have a marketplace for a music industry as it were. And Abdoulaye is integrated into that music scene very early on with his band Super Mande. So, he saw musicians like Salif Keita, and Manfila Kante circulate, as he says, within his group, but they were all there. The point is Abidjan was a rich space for popular music during that time, and he establishes a career for himself, both as a jeli, but also, in a modern sense, as an artist—and again, those two categories are not mutually exclusive, in the sense that he is servicing patrons and he is releasing records. This is all part of his life world. And so, for 20 years he does this. He gets involved with the Les Go de Koteba. He collaborates with Yacouba Sissoko, another prominent member of the community here, and they travel on several occasions to the United States, and, at various points during those tours, Yacouba and Abdoulaye decide to disembark and do something new.

Abdoulaye had already made a career for himself, and he had a family. Abidjan was his home, but at a certain point in his career, as he explained to me, he wanted to know what more was out there. “What more can I do? What can I contribute?” And so he chose to spend some time, which has turned out to be quite some time, in the United States.

B.E.: Now I have known Abdoulaye for years, but I learned things about him and his experience from your writing that I never knew. For instance, he didn't realize at first that there was this community of noble families that could support him. He did not find that community right away. Tell me what happened to him when he first came here.

R.S.: Again, this is a story I found with many members of the Mande musical community. He got started working basically at a corner store as a shop assistant. I think his first interest was to make a better living for himself. He said he wanted to see America, so I think there was a part of him that truly wanted to play with this American ideal of working hard, making a good living for yourself, sending money back home, and showing what he was capable of doing, having made this rather difficult choice to be away from his family, to be away from his home. So you know, he really made an effort early on to do that. It was a struggle for him. I don't think it was something that pleased him so much. But he explained to me that music really was not part of his world, and I don't know if he was actively seeking it until he encountered someone who recognized him or knew his name, and knew him as a singer, as a jeli. And he was asked to come and perform for a ceremony, a baptism I believe, perhaps a marriage, a sumu, or lifecycle ceremony. He is brought in and wows the crowd. He shows that he may have left music behind, but music didn't leave him. He comes and leaves a big impression, and the impression is reciprocal. It makes an impression on him too such that he thinks, "Well, here's a place where I could make a living for myself and fulfill a certain artistic sensibility, but also a heritage that I bear with me.” And music again becomes a focal point of his life, whereas he had left it before.

Perhaps it's understandable, spending 20 years doing something, then coming to a new place, and wanting to reinvent yourself. There is both opportunity and difficulty in newness. And so he must have encountered that. At the same time, rediscovering a community that acknowledged him for who he was—as a jeli, as a singer—clearly meant a lot to him, and he has made a powerful name for himself here, to the extent were even back home in Mali, he has reinvented, or at least rejuvenated his standing as a musician.

B.E.: You know, I have just been listening to Abdoulaye’s just released acoustic recording, Sara, and it just reinforces my sense that he really is an extraordinary talent. It's difficult to imagine that there was a time when he was living here simply as a worker, not an artist.

R.S.: He’s got the total package as a musician that others lack. Eric Charry makes this point, and it’s true that in jeliya, there are these forms of expression—speech, song, dance, and instrumental performance—but very rarely does any one person master more than one or two. Abdoulaye has a powerful knowledge of Mande history, which comes across in his lyrical renderings of traditional pieces. He has a beautiful voice. He’s obviously cultivated the art of song. There are still places to go, but he’s gone a long way. And he is a fine guitar player. He has got an extraordinary repertoire in his hands, perhaps not virtuosic, but a very fine guitar player. I didn’t know that about him initially. Because he has established himself so firmly and distinctly as a singer, I had no idea that he played the guitar until he took it up one day. It was a great surprise. And so there are these hidden truths to him that I think he perhaps tucks away. Maybe it is out of humility, maybe out of the sense that perhaps this it isn’t important to his career right now, but when he brings it out, it is a wonderful surprise. So, yes, he is a remarkable jeli. He is a remarkable artist. And again, those two identities seem to live very comfortably in him.

B.E.: I know about his guitar playing. I’ve had the pleasure of playing guitar duos with him. An extraordinary experience…

More to come in Part 2 of this interview, which coincides with the broadcast of New York’s Mande Diaspora, Part 2: Beyond Community. This program explores the work and musical lives of New York jeliw, outside their native community, and first airs on Afropop stations the weekend of March 6, 2009.

In the meantime, here are some links to more on the featured artists:

LINKS

Ryan Skinner’s children’s book, Sidiki’s Kora Lesson: www.sidikibaskoralesson.com

Ryan Skinner’s Two Rivers CD project: www.bafilaben.com

Jumbie Records (home of Kakande): http://www.jumbierecords.com

Alhaji Papa Susso’s website: http://tcd.freehosting.net/papasusso.htm

Mamadou Diabate’s website: http://www.mamadoukora.com

Balla Kouyate’s website: http://ballakouyate.com

Fula Flute website: http://www.fulaflute.net/index.html

Fula Flute MySpace page: http://www.fulaflute.net/source/index.html

Kelenia website: http://www.oranetkin.com/group_kelenia.htm

Cora Connection website: http://www.coraconnection.com

R.S.: Abdoulaye Diabaté is a great place to start because he has a travel story that begins earlier in some ways, and I think it's important to follow his story. He is, of course, a jeli, so this is part of his cultural patrimony. But as a young man, he takes part in a very lively orchestral, popular music scene in Bamako. This is not a jeli tradition; it's an urban music tradition, and he is very much a part of that. He spent some time in Bamako. He spent some time in Koutiala, in southern Mali, playing music. There comes a point in Mali’s geo-political history where things are deteriorating in the 1970s. It's not just Abdoulaye. It's a mass of musicians. This is Moussa Traoré. There are droughts. Politics are repressive. Resources are scarce. Abdoulaye leaves. He goes to Abidjan, and in Abidjan, under the more liberal politics of Houphouet Boigny, you have a marketplace for a music industry as it were. And Abdoulaye is integrated into that music scene very early on with his band Super Mande. So, he saw musicians like Salif Keita, and Manfila Kante circulate, as he says, within his group, but they were all there. The point is Abidjan was a rich space for popular music during that time, and he establishes a career for himself, both as a jeli, but also, in a modern sense, as an artist—and again, those two categories are not mutually exclusive, in the sense that he is servicing patrons and he is releasing records. This is all part of his life world. And so, for 20 years he does this. He gets involved with the Les Go de Koteba. He collaborates with Yacouba Sissoko, another prominent member of the community here, and they travel on several occasions to the United States, and, at various points during those tours, Yacouba and Abdoulaye decide to disembark and do something new.

Abdoulaye had already made a career for himself, and he had a family. Abidjan was his home, but at a certain point in his career, as he explained to me, he wanted to know what more was out there. “What more can I do? What can I contribute?” And so he chose to spend some time, which has turned out to be quite some time, in the United States.

B.E.: Now I have known Abdoulaye for years, but I learned things about him and his experience from your writing that I never knew. For instance, he didn't realize at first that there was this community of noble families that could support him. He did not find that community right away. Tell me what happened to him when he first came here.

R.S.: Again, this is a story I found with many members of the Mande musical community. He got started working basically at a corner store as a shop assistant. I think his first interest was to make a better living for himself. He said he wanted to see America, so I think there was a part of him that truly wanted to play with this American ideal of working hard, making a good living for yourself, sending money back home, and showing what he was capable of doing, having made this rather difficult choice to be away from his family, to be away from his home. So you know, he really made an effort early on to do that. It was a struggle for him. I don't think it was something that pleased him so much. But he explained to me that music really was not part of his world, and I don't know if he was actively seeking it until he encountered someone who recognized him or knew his name, and knew him as a singer, as a jeli. And he was asked to come and perform for a ceremony, a baptism I believe, perhaps a marriage, a sumu, or lifecycle ceremony. He is brought in and wows the crowd. He shows that he may have left music behind, but music didn't leave him. He comes and leaves a big impression, and the impression is reciprocal. It makes an impression on him too such that he thinks, "Well, here's a place where I could make a living for myself and fulfill a certain artistic sensibility, but also a heritage that I bear with me.” And music again becomes a focal point of his life, whereas he had left it before.

Perhaps it's understandable, spending 20 years doing something, then coming to a new place, and wanting to reinvent yourself. There is both opportunity and difficulty in newness. And so he must have encountered that. At the same time, rediscovering a community that acknowledged him for who he was—as a jeli, as a singer—clearly meant a lot to him, and he has made a powerful name for himself here, to the extent were even back home in Mali, he has reinvented, or at least rejuvenated his standing as a musician.