Few labels in recent years have done more to recover and share the glories of Colombian popular music than Palenque Records. We recently asked them to put together a mix for our podcast. To accompany that mix, producer Sam Backer interviewed label head Lucas Silva via Skype.

Sam Backer: Why did you start the label?

Lucas Silva: I started Palenque Records label in ‘96. I’m a filmmaker. I make movies: documentaries and feature movies about Afro-Colombia. I just started my label. It wasn’t something I was really planning. I was doing a documentary film about cumbia in ‘96 in Cartagena. At that time, cumbia was not like it is today. Nothing was going on, talking about cumbia, in Cartagena at that time.

I knew a new kind of music, a new style I never heard before called champeta. It was completely new for me. And I just met these champeta musicians doing research about new Afro-Colombian styles going on and I was so impressed about this champeta music, which was completely underground and completely unknown, even in areas of Colombia, that I decided to make my first movie about this champeta music thing. And working on this champeta scene on the champeta movie, I met many Afro-Colombian bands from Palenque and Cartagena. And they were simply great and nobody was producing them. So I thought, if I don’t put out these guys, nobody’s going to do it. And I didn’t know anything about musical production. I didn’t know anything about labels. I just started with passion, because I really was a big fan of this new sound for me.

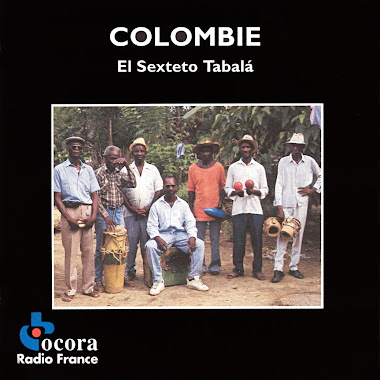

I recorded my first production in San Basilio de Palenque in ‘96. I recorded a band called Sexteto Tabalá. They play traditional Afro-Colombian songs mixed with traditional music for funerals. It’s a fantastic band that I was dreaming to record. This band never recorded anything before. They were just countryside people who were working on farms, who were working on the lands of Palenque. They didn’t know anything about recording. They didn’t know anything about the business of music. Sexteto Tabalá was a band that was playing at funerals and parties, when somebody was getting married, something like that. We did our first production in ‘96. I released this production in France in ‘98 with the label Ocora, which is the label of Radio France International. And since then until today, I’ve been producing Afro-Colombian music with a different concept--with my own ambition of African and Afro-Colombian music.

So Palenque is only concentrated on African and Afro-Colombian music until now. All of that because in ‘96 when I started, Afro-Colombian music was really forgotten. Nobody was really talking about Afro-Colombian music, even the term “Afro-Colombian music”--nobody was using it. Everybody was talking about Caribbean music, costeña music, which I don’t agree with, because Colombia has a very large African population and they have lots of music. And I decided to put my work on this label. Then I released some champeta compilations, released in France, and I started to produce my own champeta style.

For people who don’t know, can you describe champeta really quickly?

Champeta is an Afro-Colombian musical genre, which is a mix of African modern music, African pop music, like soukous, highlife, Afrobeat, mixed with some sound system music from the Caribbean coast, so it’s a mix of Afro-Colombian styles together with the influence of soukous, music from Congo, from Nigeria, from Ghana, music from the ‘70s, from the ‘80s, ‘90s. In the ‘70s, African records started to arrive in Colombia, and people were really impressed by this music and they really liked it. So more and more records started to arrive. Some people from Colombia started to go to Africa, looking for music. They’ve been to Europe also, looking for African records.

So the sound systems in the Caribbean coast started really playing a lot of Nigerian highlife, Congolese soukous, Kenyan, chimurenga from Zimbabwe, South African music, Soweto music, funky, and little by little, African musicians and Afro-Colombian musicians started to do covers of African tunes. And so champeta music was born in the ‘80s when some bands started to do African cover tunes, and little by little, a new musical style was born.

The history of champeta has a lot of similar things to the history of reggae music, because the heart of champeta is the sound systems, and these sound systems were playing African music. We created this version of African music down in Colombia with our own influences, and so, the movement that started in the ‘80s is a very complex music because you have some roots champeta. You have modern champeta. You have sound system music--more like a dancehall thing. You’ve got many kinds of champeta, but champeta is mainly very much based on Congolese soukous drum rhythm, African guitars together with Afro-Colombian singers. The style has a very strong evolution. Every year you have a new style coming out. It’s a very big scene of musicians--young musicians and all ages doing African music together with Colombian elements.

Is it better known across Colombia now?

Well, yeah. When I started in ‘96, nobody knew champeta. It was very much a ghetto music, but now champeta became a mainstream musical style, and everybody knows champeta in Colombia now. There’s a lot of champeta fans in the world--in Japan and China and the United States, Europe. A lot of people listen. Champeta has become kind of a fashion, hipster thing, and everyday you get more champeta fans in the world, more champeta musicians going on tour in Europe, a lot of new releases.

I’m very happy about this because it was a big fight to make this music go international. When champeta started it was kind of hip-hop, a very ghetto music, done by poor people. And now it has become a worldwide thing--in Canada, United States, Europe. It has become a phenomenon. We talk about Afro-Colombian music. Champeta is without a doubt the new thing.

Your label covers other kinds of Afro-Colombian music too, right?

Yeah, with my label, we talk about Afro-Colombian music, we have Caribbean coast music and music also from the Pacific coast. And the Pacific coast is a very big area, populated 90 percent by black people, and so, in the Pacific, we have curralao, chirimía, aguabajo, a lot of different styles, from traditional to modern music. And I’m producing some new records now in the Pacific coast of this curralao, which is a balafon music, marimba music.

It’s beautiful. I know that music--some of it. There’s a lot.

Yeah, it’s very interesting because on the Pacific coast, you have a very strong African heritage from countries like Mali, like Senegal, Mandingo influences. In the Caribbean coast, we have a lot of Congolese, Angolan heritage, and in the Pacific coast, we have a different heritage, like I said, Mandingo, from Senegal, from Benin, from Nigeria, Cameroon, from other areas. So, my work is about doing research. Because in Colombia, there is a lot of unknown instruments, rhythms that nobody ever recorded before. So, the thing that I like the most is to go to the jungle in the Pacific coast for example now, looking for this forgotten musical styles, looking for the traditional musicians, who are the teachers of the youngsters.

And I’m doing new records in the Pacific coast of chirimía, of curralao. These are fantastic music and a very strong tradition. I hope to release them very soon, because the Pacific coast… The Caribbean coast always had more promotion when we talk about music, because Colombia--everybody knows Colombia. But chirimía or curralao--very few people know about them. So I’m working on this now, actually.

Are there any artists that you’re working with now that you’re particularly excited about? Particularly stand out?

Well, yeah, when we talk about artists that I like, people that I like the most are hidden in forgotten villages, very far away places. Somebody that nobody knows until I release their production. And I’m really crazy about this… The work that I do is a bit anthropological--collecting music. But from this very traditional thing I made also remixes, different versions, modern versions.

If you talk about Colombian music, the kind of musicians that I really admire today would be Ramiro Beltrán. Ramiro Beltran was a musician from Barranquilla who did some psychedelic music in the ‘80s--some Afro-funky tunes. There was a legendary label in the ‘80s also in Barranquilla called Machuca. They produced great Afro-funky tunes, psychedelic Afrobeat stuff, and I’m doing research on this period of music in the ‘80s. I released one compilation together with Soundway Records in England, called Palenque Palenque. It was a vinyl--three LPs. In these three LPs, you can listen to all this music I’m talking about. Beltrán, Cumbia Siglo XX, Abelardo Carbonó, who was sort of the father of champeta in Colombia and also Afrobeat music. All these pioneers of music now they have about 60, 70 years old, and I’m working with them because I want this ‘80s sound to come back--the Colombian psychedelia, the Colombian Afro-funky tunes and the Afrobeat style.

Also a musician that I admire very much, and the music that I admire the most is music from Nigeria in the Igbo area--musicians like Oriental Brothers, which was a band that started in the ‘70s and they’re still playing. And I’m very much into this highlife thing and music from Cameroon. African music is my favorite thing ever.

Can you tell me a little bit more about these upcoming projects for the label?

With Palenque Records now, I’m doing also some movies. I’m doing a movie about psychedelic music in the Caribbean coast in the ‘80s. I’m also doing a movie with actors and things like that about the making of champeta in the ‘80s and ‘70s, but I’m working in the Pacific coast, doing a record of currulao, balafon music. So we have a lot of projects of new releases going on.

We’re going to release a record next year from Abelardo Carbonó, a very brilliant guitarist from Barranquilla. Every year we release two or three productions. Actually, we are producing six or seven different records, because Afro-Colombian music is a very big thing. Colombia is a big country, so you have a lot of different rhythms and there are too many musicians to produce. So I hope to release next year this Abelardo Carbonón production and another compilation looking for old tunes--psychedelic and funky stuff that I hope to release very soon on vinyl.

There’s too much music going on. Doing research about music is wonderful because you find really forgotten things. And all of my work is to reveal these masters who initiated our music and the pioneers of production in Colombia, the pioneers of African music.