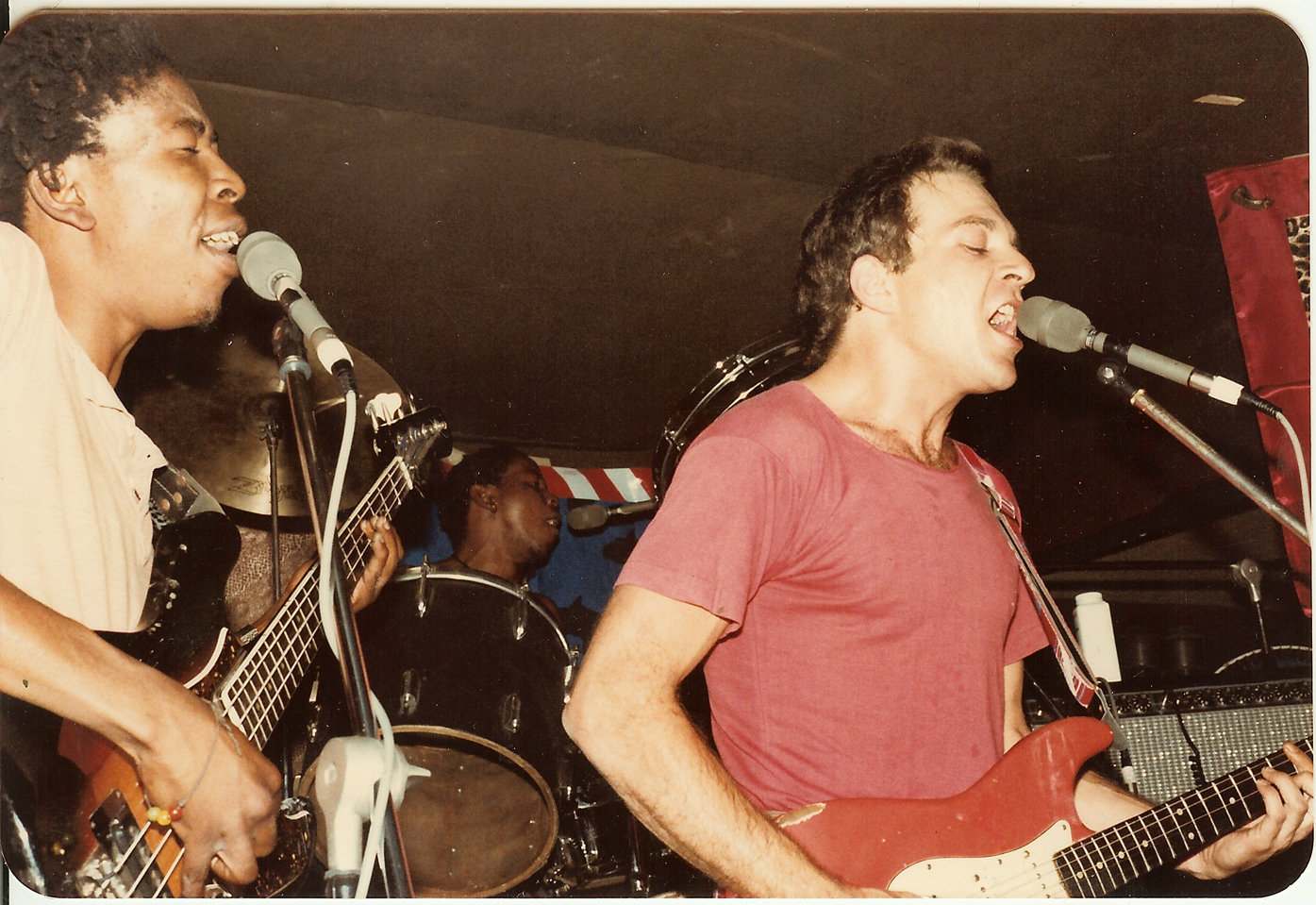

As part of our show on Punk in Africa, we talked to Ivan Kadey, guitarist for the pioneering group National Wake about his musical roots, experiences, and his thoughts on Punk. To learn more about punk in southern Africa, listen to the full show!

Sam Backer: Hello Ivan- Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with us. Can you tell us about how your first started playing music, and when/how that first became connected to politics?

Ivan Kadey:You know I started playing music when I was 11 or 12. I’d always loved music, and loved singing with records and i'd always imagined- dreamed of being a musician, a singer, and around 11 or 12 I got my first guitar. I had to go through all sorts of shenanigans to actually be allowed to get a guitar. and when I got it, I just got a chord chart and taught myself some chords, and learnt how to tune it. I never had any lessons, I just picked it up. As soon as I could put 2 or 3 chords together, I started writing songs. It seemed to be the most immediate way for me to express myself, and it really was a great medium for me to do that. It was a very natural thing for me, it was totally unschooled, and unprompted by anyone else. It came from a really inner need to deal with emotional stuff. So music was always a force in my life that was a means of expression.

Politics, I don’t know how one, growing up and being born and living in South Africa, couldn’t become involved in politics. I mean- also, what’s one’s definition in politics? I’m not talking about organized activity, just the regime we were living under and the way it came into all aspects of life, the racial divide that was established in the country was so apparent even to a child, one could see the way people were treated, so I think if one had a conscience- and I think most people start off with a conscience and an awareness- you're part of that from the moment you're born.

SB: When did you first start to perform out?

I.K.:There was always a desire to actually perform for an audience. I think most musicians, most people playing music, want to express themselves, want to get to an audience. When I was a teenager the folk movement was quite strong in South Africa and Johannesburg, and there were a couple of clubs around. Some guy in my neighborhood started a coffee shop, and my buddy and myself formed a duo and auditioned, and we got a slot. So when I was 16 and 17, every weekend we’d perform- largely folk songs, some of them protest songs. We knew Masters of War, Eve of Destruction- we were attracted to more serious material, but we also played a lot of just straight folk stuff, Simon and Garfunkel, things like that. And I’d been writing, and occasionally we’d actually play one of my songs and perform them, and...that’s how I started!

Then, later, I went through the rights of passage of a white South African. I had to deal with the army, and that was a part of my life for many years, and I also went to University to study architecture. I’ve always had these two passions, architecture and music. At times they’ve actually come together, and I designed recording studios for many years.

SB: What kind of music did you grow up listening to? What was available?

IK: Well, you know, a lot of stuff was available. South Africa is interesting because we got music from the USA and from the United Kingdom. There were record stores that were importing the stuff directly as soon as it came out in either country. They’d import it, so we got to hear most of what record companies were putting out. Those days there wasn’t the internet, so you didn’t get more obscure stuff, but I was listening to everything, I mean as a child I’d grown up listening to my mother’s taste in music which was great - you know, Nat King Cole, Harry Belafonte - a lot of the musicals of the time. Then my aunt opened a record store in the southern suburbs area, and I discovered Rock n Roll! So from the age of 5 or 6 I was listening to Little Richard, Elvis Presley, all that stuff. I mean we were exposed to whatever was going on- a lot of the stuff from the UK, Tommy Steele, you know early rock n roll from the UK also came to South Africa.

SB: Did you have much of a connection to more South African styles?

IK:It's something one doesn’t often mention, but it’s part of one's life growing up there- from the earliest age, kids have African nannies, women looking after them who would be doing the house work. There was always African radio stations on, and from the earliest days, we would be strapped to the nannie's back, bopping along to African music. So that I think goes very deep into one.

SB: What lead you to adopt such a strong political tone in your music?

IK: At the time of National Wake, living in South Africa, if you were going to do anything creative, you had to deal with being honest in a totally flawed situation. And what’s the meaning of art in such a situation? I mean many people believe that art’s free of a necessity for addressing an unjust political situation, and some art is and some art transcends any situation. But a rock n roll band in South Africa, there’s sort of the spirit of rebellion. There was really a lot to rebel against.

I’d been writing protest songs from my earliest years, you know, a lot of my songs dealt with that situation, it was just very natural. At the time that National Wake started, I had already moved from acoustic to electric. I’d been getting more and more into playing rock and a sort of rudimentary reggae which I had come across more recently in my life.

SB: How did you first get interested in Reggae?

IK:A Bob Marley album! [laughs] Positive Rastaman Vibrations was the first reggae album I’d ever had. Obviously I heard ska stuff before, but the first album to really blow me away was Bob Marley’s Rastaman Vibration. And then I got into his other albums. But the social commentary, the meaning of that music, I really got that, it was inspiring

SB: When you started National Wake, you were living in a group house which, I believe, was very important to the band's development. Can you tell me about that scene?

IK:Well, I was living in a communal house, it was a whole lot of students, and some people were working, it was a place were one could really just get on with one's life. There was a certain asylum, a lot of things were done communally but it wasn’t really any sort of kibbutz like situation or anything like that. It was quite an open house, and there was always an underground of people who were outside of the system, who were against the system, who were involved in whatever measure of trying to change the system. There was a flow of people through this house of all races and colors and all persuasions.

SB: How did the band first come together?

IK: I met a guy, Mike Lebisi, and we used to jam together. And he kept telling me he'd wanted to introduce me to these guys he knew in Soweto. And finally the day came, and they came over to jam and to rehearse- it was a place where they could hang out. And we started jamming together- it was the Khoza brothers, Gary and Punka. There was a meeting, and it worked on many levels. The music we made really had soul, it had spirit, and there was something happening there. As I’ve said many times, there wasn’t any ideology involved, just we knew this was an incredible thing we could do together, and it actually just broke through all the barriers, and all the impossibilities one imagined and we made this music. And we had this communal house and it became the center of activity, and eventually we were all living in this house together and getting gigs, and the gigs were amazing because Gary and Punka had connections through their previous bands. Gary had been in the Flaming Souls and they had a band together called the Monks, and they played a lot of the township clubs and various places. That opened up to us, and we got gigs in and amongst the University circuit, the alternative club circuit, and the township circuit, and somehow we managed to just go and do these gigs and stay under the radar, and develop a following in these places.

SB: How did you guys connect with punk? How much of an influence was it on your music?

IK: The connection with Punk? That was happening at the time, and we were aware of it. Punk was mostly an attitude! There was a group, South Africa’s first really genuine punk band called Wild Youth and we did a number of gigs with them. Some of that rubbed off- the song black punk rockers is really inspired by the sounds of Punk Rock. I mean the lyrics are. I don’t know if National Wake's music is strictly punk, but the spirit is certainly Punk. And we were exposed to music coming out of the UK, I mean, we listened to The Clash, we listened to other bands of that time. But the attitude of just getting up and making your music, not actually having to be apart of the establishment- National Wake really came out of nowhere on the music scene in South Africa. We got our first gigs and there was an immediate response. There was one music magazine in South Africa at the time, and I think after our second gig they put us on the cover which was sorta crazy, because we were suddenly right out front- announced ourselves, it was very punk.

SB: Another important event in '76 was the Soweto uprising. How did it impact the art you were making?

IK: The uprising of 1976 was an incredible watershed in South Africa. Things had reached a point where school kids were standing up saying we’re not going to take this anymore. In many ways it was an inspiration to people who were against the system to measure their commitment, and...things got much more serious after that. It was much more intense, and if you were going to get up and say who you were, the stakes were higher. So if you wanted to actually speak, you just had to be more potent in response. And I think the punk thing and that sort of attitude went hand in hand- really just standing up and speaking one’s mind. Loudly.

SB: What was the relationship between National Wake and the punk scene that grew up around you?

IK: Well, we were part of that, but we didn’t make it happen. No one band makes the scene happen. There was this energy... South Africa is very complex because there was a change in leadership in the ruling governments around that time. I mean, believe it or not, PW Bhotha who became the prime minister of South Africa in the late 70s, actually brought some new ideas to the table. He soon retracted his more open ideas and became hard as rock. We all know that now... but initially there was this idea that there was going to be change in South Africa. And I think that released a lot of energy. There was some idea that something good could come out of this politically. That changed, and it’s interesting because the early Wake songs are a lot more hopeful about getting it together, about actually all joining together, and making.... you know this is the wake of a nation, you know this is National Wake, the idea of people coming together and forming a new society or being the seeds of a new society, and that was in the air. But things did get progressively heavier, and if you go through the whole Wake evolution, our songs and our song writing and our sound, went from a much brighter sound to a heavier sound. Till eventually the last sessions were sounds foretelling bombs and burning.

SB: How did that sound come about?

IK: You know, I had songs, Gary and Punka had songs, Mike had some inspirations for songs. We did jam some songs together that came out of our practice room. There was a very strong funk element that came with Gary and Punker from the Monks, which was essentially a funk band. We all had rock roots, I had quite strong folk roots. That’s where we started and then, later, Paul left the band and Steve Moni joined us, and he had a whole history in bands, you can hear it in that mixtape, the Safari suits. I think one of the cool things about the [National Wake] mixtape is that Keith and Craig put together some early Flaming Souls tracks, a Monk track, God knows where they found a Monk track but they did... We spent a lot of time in our rehearsal space which was part of our house. It was in the garden of the house, and we’d taken this old decayed summer house, which had a thatch roof which we draped with tarps that someone had actually stolen from the army. We’d enclosed part of the summer house as our practice room, it was actually fantastic space.

Sessions just started with jams and often those jams became songs, and as the group evolved we were getting into reggae grooves. You can hear it on the album on the song Superman. It’s sort of a very early basic reggae track. But as the band evolved, everything started fusing. I'm thinking of a song like Bolina, which is also on the album. We first started jamming that when we were doing gigs in Swaziland in a very sub-tropical sort of environment. And you know, it might be fanciful, but I really hear that in the track, there’s a slightly East African edge there.

It’s hard to say how sounds develop, but I think it’s all part of that. The landscape one is in gets into the music, I’ve always felt that. So it just got more complex, and we just knew, we understood each other. By the time we were doing that music, we’d been playing together for 2 to 3 years, and things would just happen. We understood each other well, and there was a certain culture we’d built up and we moved quite freely through funk, reggae, rock. It was really quite amazing.

SB: I know that you took some pretty amazing tours through the country during that time. Can you tell me about them?

IK: We were fortunate- Very early on we got put on this, what’s called the peninsula tour. Our friend Neil Bolitho was this incredible artist, an energy man from Capetown who’d been part of the formation of Safari Suits and Housewive's Choice, which were early new-wave/punk bands from Capetown. He called it the "Riot Rock Tour" which was a tour of the Cape Peninsula. I think there were four bands on the bill, and we were invited to come down. It’s quite a complicated story, and I’m not going to all the ins and outs but there was Housewife's Choice, Safari Suits, Wild Youth, and National Wake. Those are the ones I’ll remember, and they might be the only ones- if I’ve forgotten any other bands it’s not any fault of their’s, it’s just my memory.

We went down to Capetown on this tour and it was great. We did like four venues around the peninsula, and then we had a couple of club gigs in Capetown, and then we did a festival on our way back to Johannesburg. And then there were trips we took to Swaziland, which were on our own initiatives, and through our own connections. Doing townships all around Johannesburg... Sharpeville! We became pretty much regulars at the Sharpeville night club, which was pretty amazing to be in such a place, such a historic site in terms of the struggle. But we loved playing in Sharpeville- it was an amazing club. We got to see rural parts of the country. There where clubs all over the place that we somehow hooked into, little towns outside of Johannesburg, and everyone of those gigs was an adventure. Yea, we did see quite a lot of the country with the band.

SB: You've talked some about the struggle. How did you understand National Wake's music in that broader context? Did you see playing in this band as being a part of that struggle?

IK: Music.... You know, what does Bob Marley say, “When it hits you feel no pain?” I mean it was part of the struggle, but it was a joyous part of the struggle. Just being together and making our music was a really positive energy. Just to say “hey this is possible, it's possible to do something of meaning and joy together.” And that’s what we were. Life was a struggle! It wasn’t easy to keep the band together, for ALL the reasons, for all the pressures impinging on us from outside, and the pressures within. Like any band, there were all sorts of things going on. Ask anyone who’s been in any band and they’ll tell you what it’s like. But when we got up and played music, that was it, that made it all worth while. We got a couple of gigs in the streets in Johannesburg, you know, for various reasons. We did this amazing gig very early on in our performing life, in Rocky Street. Some guy had this clothes store, there was an open courtyard across street, which has since been totally closed in, and he decided to do a store party with a performance in the square and we were the band. I always found that those gigs on the street were amazing because their was no segregation, the streets were open and it was open to everyone. The spirit was amazing, and in fact, on the National Wake Youtube site, you can see in the song, " Everybody Loves Freedom", which was largely shot at that gig on Rocky street, you can see the people coming together and just dancing. That was our contribution in many ways. The lyrics of our songs referred very directly to the situation in South Africa. I say the band was not ideologically directed or motivated, but we knew, we knew what we stood for.

SB: Can you tell me about your song International News?

IK: It’s hard to say how the lyrics come, but the first thing that came to me with that song was really the chord pump, the engine of the song is what’s happening chordally in the rhythm guitar. And just the way my mind would go, just thinking of the situation in Soweto when trouble came down. It’s many things, sometimes I wonder about really explaining lyrics, but it’s about censorship, it’s about the way the government controlled the news, it’s also about going into Soweto, and there would always be this smoke from the wood fires. It’d be like a blanket of smoke over Soweto, in many ways the song starts with they put a blanket over Soweto and it’s really about a news black out. They would call it a blanket ban, or a black out - a news black out. The papers were not allowed to report what was going on and they would do it. There were very strict rules about what they were allowed to report on, but the song really deals with that some of them would go around it by reporting what other news organizations from outside South Africa were reporting. So they would say “Associated Press International reports that South African troops are 50 miles outside of Luanda, the capital of Angola.” Then I suppose there'd be some sort of legal battle where the government tried to block that and then they’d say “Well we’re just reporting what other people say." That’s what was going on in South Africa. And that song's really about how strange it was, and how weird it was that one would live in this bubble of censorship and propaganda, and you’d go to the movies and you'd know what was happening in the country and in the townships, 20 miles away. And in the theatre there’d be this apparent calm, and there’d be news reels and what they’d show you would be horse jumping in the UK, or a yatching race between Rio and Cape Town - that song’s about all of that and it’s also about times a coming when they just going to put a blanket on everything. I mean, people have asked me "Why is this song so fast? Why is it at such a pace?" And I’ve often thought about it, and it’s really because you never knew when you would be shut down, you know? And there’s a sense of urgency to get this out before it gets shut down.

SB: I know that eventually, you lost your house. What was the effect of that?

IK: Losing the house meant that a crucial piece of what held us together was lost. There were many other factors, I mean we’d been going for 3 years and there was always a pressure. We all felt it, and I think after the album was released there was so little coming back at us from the culture that could have been supporting us. We were very dispirited. I'm sure that there was pressure put on the record company about that album. And part of the National Wake story that I haven’t really spoken much about was that as we really started making it, and we went to the Chelsea which was the club for bands to showcase in South Africa, in Johannesburg, we started really hitting up against the racial segregation laws. Because most of the other venues we played, we could largely ignored all the racial dividing laws, but suddenly we’re getting to these clubs, and they were high-stake places, and it wasn’t easy to just have all our fans come into the club. There was a built-in catch in the whole thing we were trying to do. The more well know we became, the more pressure we got. Some of the members of the band really were cracking under the pressure. So we lost the house which was an asylum, it was a place where we had established our own world, you know? and after that, it was very hard to keep things going, both financially and in terms of having a space which was ours that we could hold and actually culture our creativity.

SB: How did you record the album?

IK: Well the album. We just decided that we had to get these songs down. Part of the story is we saw the value of what we were doing. We went to friends, and we raised a thousand rand, and that bought us some backdoor time. We did that album Sundays and late evenings, and we got a special rate. And for that first 1000 rand we laid down the back tracks for half the album, and then from another friend we got another 1000 rand and did some more recording. and it's basically going down live with really good recording equipment. And then when I had the back tracks, I started shopping it around to the labels who would potentially consider completing this album, and Benji Moody at WEA dug the material and was prepared to put up the other 2 or 3 thousand rand to do some overdubs. The album was not a lavish production, it was bare bones stuff. And in fact, we finally lost the master tape because we couldn't afford to buy the master tape, the 24 track two-inch master tape. and a number of years later, someone came to me and asked to remix the album, and we went looking for the tape, and we couldn't find it. It had been wiped. It was just our own sense of self preservation that got the music down.

SB: A final question- What do you think National Wake's legacy is?

IK: For many years ii thought it was gone, part of my life that was very meaningful and valuable to me, and people hardly seemed to be cognizant that it ever happened, or take much notice of it. But its really amazing, in the past 5,6, years, there's been this interest in the band and the music, and it seems to be growing, which is pretty pleasing. In terms of what it means today, for people now, I mean, a young musician in South Africa who goes by the name by Cami Scoundrel just recently wrote a piece on the meaning of National Wake's music to her today, and she draws parallels to the situation of different races in south Africa today, and how looking back at what was happening with national wake during apartheid, there was a certain spirit that she wishes existed today, of what can be done if everyone comes together in dance and in song. So it's interesting, what it's come to mean today.