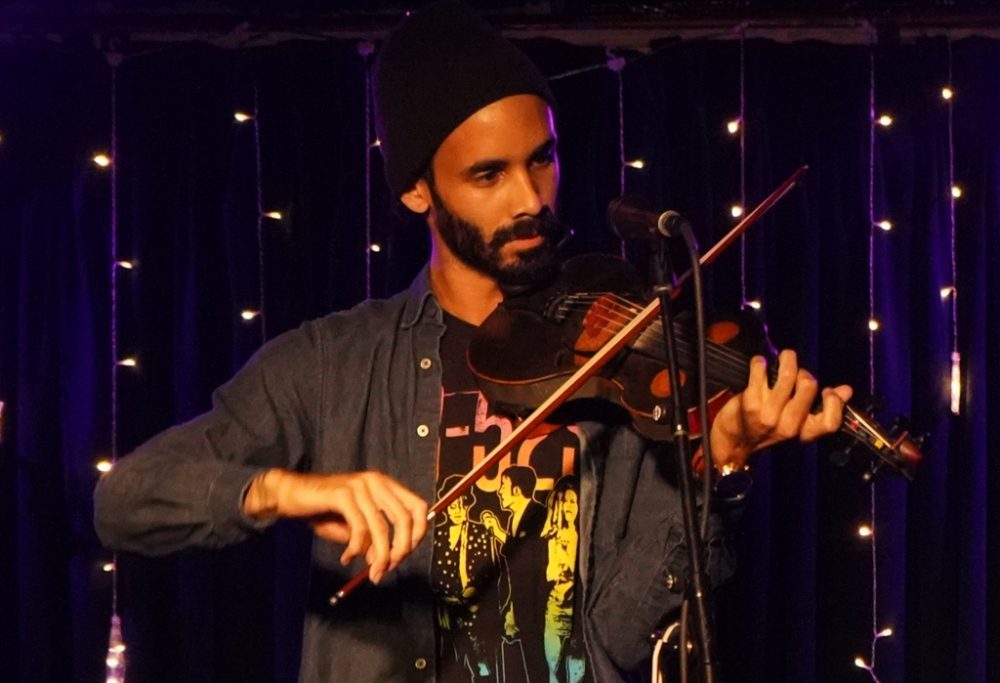

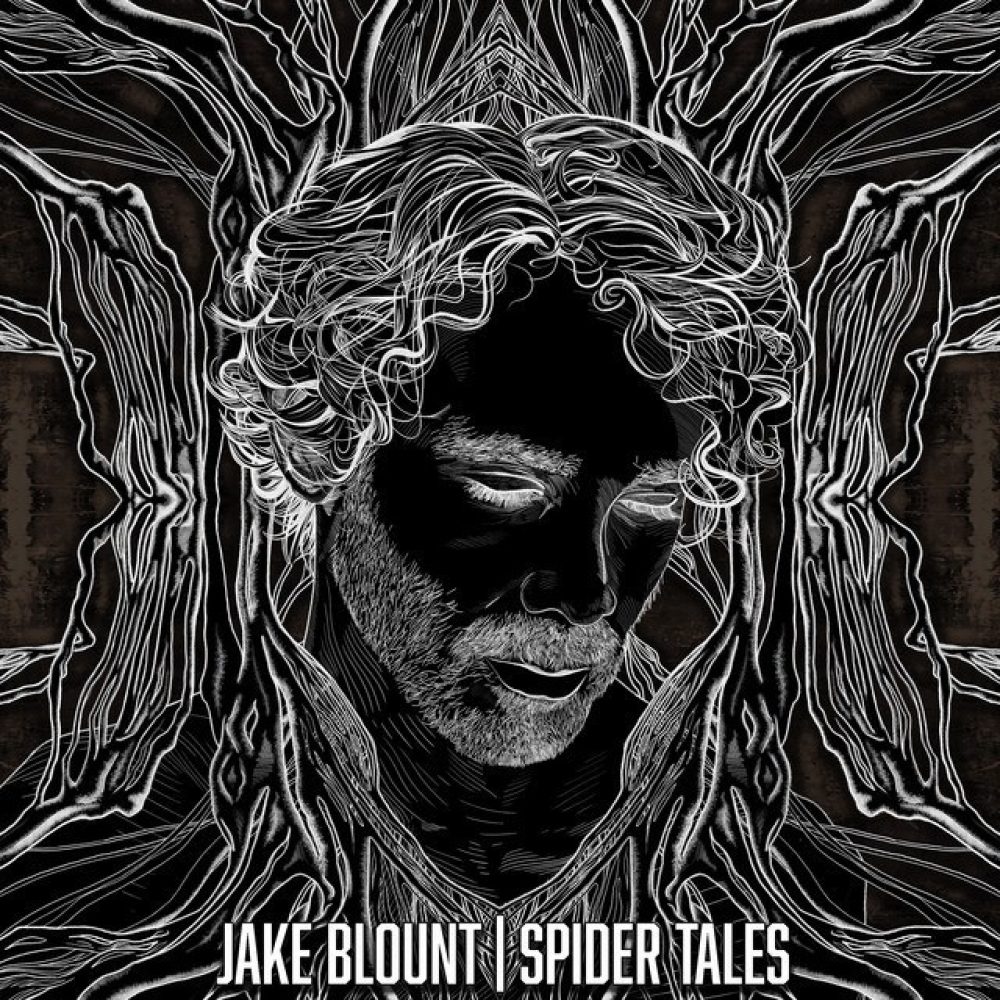

Jake Blount is a talented young African-American fiddler, singer and banjo player. He’s made it a specialty to focus on compositions by, as he put it in a recent concert at Café Nine in New Haven, CT, “dead African-American composers.” We received his 2020 album Spider Tales and were immediately captivated by his sound and this unique concept. Banning Eyre reached Blount by Zoom in his home studio to discuss his career and music. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Well, you’ve got a fancy set-up there.

Jake Blount: Yes. I have had little else to do but perfect it over the past couple years.

Where am I reaching you?

I am in Providence, back at home.

That's a good town. I have a banjo-playing friend who lives just south of you. We went to Africa together some years ago and he was exploring the roots of the banjo.

Awesome.

So your album, Spider Tales, came to me out of the blue. Your publicist sent it to me, and I was immediately intrigued by it. So I came to see your show and loved that. I'm interested in what you do. But let's start by getting your story, your background, how you came to music.

I grew up in Washington D.C. I was born in 1995 so I had the strange experience of being in D.C. while it kind of turned from the gritty, arts-focused place that it was, into a much more yuppified, different scene. I would call my household casually musical. My parents and sister love music, but I'm the only one who really took it seriously. But everyone kind of dabbled in something.

I wound up going to a lot of concerts when I was in high school. I had a friend whose mom was like “the cool mom.” She would take us to all the cool DIY shows in town, and we went to this one that was in an Ethiopian restaurant on U Street in D.C.

Adams-Morgan, the original home of Afropop.

Yes indeed. It was this band Megan Jean & the KFB playing. It was a woman playing a washboard and singing, and this guy playing a banjo, and I had just never before seen anybody play banjo like he was playing it. He was playing what I now know as the claw-hammer style. So I went up to him after the show and I said, "I’ve never seeing the banjo played like this, what are you doing? What's the story?" And Byrne Klay, the banjo player in that band, told me then and there that the banjo was descended from African instruments and that it had come over into the United States in the hands of enslaved African people, which I did not know. And of course being interested somewhat in the musical traditions of my own ancestors, I wanted to find out more about it. So that's really what inspired me to get into it.

You were quite young when that happened.

Yes. Fifteen, I suppose.

And did you play banjo then?

No. I played electric guitar. I started electric guitar when I was about 12, but I never really got good at it, so I was a little bit musically adrift at that point in time, but I did wind up looking more deeply into the banjo. I think I did the opposite for most people where I started researching it, and then I went and got the instrument. I think most people do it the other way around. But that was the start for me. It was having this conversation outside an Ethiopian restaurant on U Street.

I imagine you’ve read Laurent Dubois’s book The Banjo: America’s African Instrument.

Yes.

I read that last year when I was doing research on the Black roots of the banjo. Fascinating stuff. I understand that for a long time, probably still, a lot of banjo players had trouble dealing with the instrument’s African origins. You must've encountered that.

Yes.

So I gather from your concert that you specialize in Black old-time music. How did that come about?

Well, when I got to college, this thing started taking root for me. I got my first banjo sometime before I went to college, and when I got there, I went to one of the professors who people told me played the banjo. And I went up to her and said, "I hear you play the banjo. I think I need to know you.” She became my advisor and I got to spend a lot of time digging into banjo history through her class.

I wound up creating my own major, as you could do at my college, which was Hamilton College. So I wanted to create my own major in ethnomusicology, anthropology, music and American studies, which went over pretty well. But really my focus wasn't so much old-time music but just early Black folk music generally. And at that time, I was connecting more to the string band stuff than to people singing spirituals or whatever. So that just wound up being what I specialized in.

I did two theses when I graduated. One was on old-time music, and one was on Black folk music, which turned into my first EP Reparations. That's kind of how the whole thing took shape.

We did a show about the African-American String Band Tradition some years back and I got to interview Howard Johnson, which was really a trip.

Amazing. I'm so jealous.

You can still find that show on our website. It was really eye-opening for me. And then when I went to Mali in the ’90s with my banjo-playing friend, it was very interesting. Many people played the ngoni, the spike lute, and virtually every one of those musicians could pick up Dirck’s banjo and play it. They might've retuned it a bit, but it was instantly familiar. And that was surprising because there was really no presence or awareness of the banjo in Mali, not the way you would find in Anglophone countries like Ghana or South Africa. Those are places where Dixieland music penetrated, but that was not at all the case in Mali.

So I note on your album that you play a banjo that has a very soft, round tone. Tell me about that instrument.

I have two banjos that I play mostly. The one that you saw me play live was one built by my friend Will Seeders Mosheim who has a company called Seeders’ Instruments. He is up in Dorset, Vermont, and he's a fascinating person. He grew up the son of a very renowned furniture maker, so he spent his whole life in a workshop, and when he got older and started playing the banjo himself, he decided, "I'm going to start making these now." And I just think he's the best in our generation, or at least one of the best. He's fantastic. So I'm very excited to have one of his banjos. That's the main one that I play these days. I do have a nylon string one, which is probably what you're thinking about from the album.

Yes, the one we hear on the first track, “Goodbye, Honey, You Call That Gone.”

That one was built by Renan Banjos outside of Richmond, Virginia. It's kind of a hybrid instrument between an earlier minstrel-style banjo and a more modern one. It has that wide head, that calfskin head. It has those nylon gut strings. And it has the shallower, thicker pot that you associate with modern banjos, so it's not quite as fragile or cumbersome as minstrel banjos can be.

It has a beautiful sound, and your tone on the fiddle is gorgeous.

Thanks.

Given your focus on African-American string music, I wonder if you've done much exploration of African folk music, digging down to those deeper roots.

I don't think I've done that to a level of depth that I feel comfortable presenting: "Here are the connections between the two." There are people who've written books about that, and I am not those people. But I just got my Spotify stats today, and my top genre was Afropop. So I listen to a lot of African music. I think at this point I'm less oriented as a musician and a listener toward old-time music, so I'm not thinking about that specifically. I do think there are a lot of ways that the structures are related, in the way that it's multiple instruments with different rhythmic ostinatos going over each other.

It's all lines, rather than chords.

Yes, lines that are chopped off at different points, and putting it together makes a really exciting sound that kind stretches and very hypnotic way that can sort of warp your perception of time, depending on the speed that is going. So I think the overall feels are very closely related. I think the other thing that is closely related: I love the vocal timbres. I spent a lot of time going to church with my grandparents, and just hearing the way that people sang, the way Black southerners sang. I listen to older recordings of African folk music, not so much modern stuff, but old traditional stuff, and I hear a big connection there in the way that people are using their voices.

Of course that isn’t necessarily exclusive to African music, but it's a heritage that is there. There is also the same high strain sound in a lot of indigenous American music. So that's another connection.

You know, when I was watching you play and also the band before you, the Moon Shells, it reminded me of an idea that I've had for a long time. I think it would be great to take an American string ensemble like that and have them arrange a set of West African songs, whether it's palm wine or Mande songs, Wassoulou songs, or just skiffle. If you have a combination of players and singers from both sides, I think it would be a great project that would demonstrate these connections without having to explain much. Does that sound interesting to you?

Yeah, totally. I love that stuff. There was a skiffle band in D.C. while I was still living there that I went and saw a bunch of times. They were a riot, really fun to watch.

Nice. I gather that all the composers on the album, some of whom I recognize, are African-American composers, and you mentioned in your concert that that's “your thing.” Is that an identity that you're sticking with as you move ahead?

Yes, but it's changing. I've always been interested in learning and playing more kinds of music than just Black music. I just think as someone who's going out and performing, I'm not going to go out and perform music from West Virginia, where I learned a bunch of my playing, just because I'm not from there. No one in my band right now is from there, though people have been in the past. We just don't feel like it's our job to present that to people.

In my course of learning, I didn't start seriously playing music until I was 18 or 19 years old, even though I had been playing guitar for a long time by that point. I hadn't really been focused about it. And now I find myself coming back to electric guitar and going to other stuff, and just taking in all different styles and types of music that happened in this country. I started out with this old-time, but I've been getting really deeply into religious music, and that features pretty prominently in the stuff I've been recording lately. I've been digging into blues and rock ’n' roll and seeing how those things intersect and overlap. It's been really interesting.

I can relate to that. During the pandemic, I've had a lot of time to read, and I've done a lot of reading about African-American history, seeing it with new perspective after spending so much time thinking about Africa. This has also brought me back to a lot of American music, including yours, and hearing it with new ears. Let me about the last song on the album, "Mad Mama’s Blues," and also the song that you played live by Alberta Hunter, "You Can't Tell the Difference After Dark." Both come from Black women composers.

Part of the reason those songs were interesting to me was because of what and where and who they came from. One of the systemic problems that we have with folklore and folklore collectors from back in the day is that they're going out collecting this music, writing it down, recording it on a wax cylinders or what have you, and that's the record that remains of that oral tradition. But, they weren't going out and recording Black musicians in the same way that they were white musicians. So that's a problem. And it means that there's a lot less repertoire preserved from what Black string bands were doing in the day. However, the other side of that is that they were recording even fewer women than they were Black people. If you go back and look to the string band repertoire, I can probably count out the women who got recorded in a serious way on one hand. And none of them are Black women.

So I have felt weird all this time knowing—through books like Way Up North in Dixie that talk about the Snowdon Family Band—that there were Black women playing this music. They were part of the history. They were part of transmitting and shaping this transition and were written out by the people who promoted themselves as conservators of the tradition. It's a problem, and it's upsetting. So part of my desire to put “Mad Mama's Blues” on there was to have something by a Black woman. I didn't know where a lot of that repertoire would fit, but I think blues and jazz stuff was really the gateway of Black string band music into a commercial space. Because Black string band musicians were not commercially recorded. But on those early recordings, those early jazz recordings, you can hear Black fiddle players, and you can hear banjo players on the big-band stuff from New Orleans back in the day, because the guitars at the time weren't loud enough.

That's where you hear us start to emerge, and it's also where you start to see queer Black people take center stage, because so many of those blues queens of that era were known also to have relationships with women.

Fascinating. How is that known? Through oral history?

I think it's a mix. I think it depends on who it is. You have someone like Lucille Bogen singing a song like “BD Woman Blues,” which stands for bull-dyke woman blues, about how "soon bull-dyke woman won't need no man." That doesn't leave much room for interpretation. But then there are cases like Ma Rainey, who is the subject of this play that got made into a movie.

A good movie. I loved it.

Absolutely. But she is one where there are kind of conflicting narratives. Some people interpret relationships in her life as queer relationships. Other people do not. And at this point, it's not ever going to be known for sure. And I think that's where you get into a really dicey situation where people like me dealing with old music, and you dealing with old music, often get into this thing where throughout history we've treated people being queer people being LGBT as a sort of "innocent until proven guilty" situation.

Right. It's hard to go out on a limb.

You can't prove beyond a reasonable that this person was gay. Why would you be able to? At that point time they would've had to hide it all the time. Of course you can't prove it. But we’re held to that standard of proof, and that means that a lot of times those narratives also get erased. In the same way that Black women didn't get recorded, even in the cases where queer people did get recorded, usually we’re told, "Oh, there's a reasonable doubt, therefore we have to assume that they’re straight." That's the default.

So to me it feels important to be working with that blues queen repertoire, because I want that part of the tradition to be seen and understood and recognized. I don't think that a lot of the old-time and bluegrass musicians I work with pay much attention to that. But I really think there's a close kinship there. I think that breaking down the boundaries between those genres, which were really born out of attempts to segregate the early music industry rather than any stylistic difference, is part of what I want to do.

So interesting. You know, there's one line in “Mad Mama’s Blues” that really jumped out at me. “These bones are going to rise again.” I spent a lot of time writing a book about the world of Zimbabwean musician Thomas Mapfumo, and a version of that line keeps recurring. In the 1890s, the Shona people rebelled against the Rhodesians, and a female spirit medium named Nehanda played a role in that uprising. At the end of it, she was executed, and just before she was hung, she said that very line: “These bones will rise again.” And some 70 years later, when people rose up to overthrow the Rhodesian state successfully, it was often seen as a fulfillment of Nehanda’s prophecy. It's that idea of being defeated, but knowing that victory lies in the future.

That's very interesting for me to hear. One, because I substituted in that verse. The original one in the song is about her committing a mass shooting. And I thought, "This doesn't play in 2020." It was something about how she was going to take that old Winchester down off the shelf and when I get through shooting, there won't be anybody left. And I'm like, "I get that this didn't seem like a real threat when you were alive, but we can't do it today." So I wrote that verse. And I took that line—These bones are going to rise again—out of one of the old Lomax collections. So that was present in our oral history going all the way back there.

So who knows where it originated?

I always assumed it was biblical.

That makes sense.

That whole thing where Gabriel blows his trumpet, I will rise again. I will rise again. That thing. Because that is such a motif in American folk music. But it never occurred to me that it would reference something earlier or different, going all the way back to Africa. It could just be from theology in Africa.

Exactly. That was a time when missionaries had been very busy down there. And they still are. So you’re working on a new album now. Tell me about that.

I am limited in how much I can say, but yeah, I’m about halfway through mixing, which is exciting and extremely frustrating. It’s the first thing I’ve ever recorded basically in here. I moved while I was making it, but I made it in my house because the recording studios kept opening and closing because of COVID the whole time. So I got some microphones, I got some preamps, all that deal, and put together a record here that actually does a lot more engaging with explicitly African music than anything I’ve done before. I think you will like it a lot.

Can’t wait to hear it.

I’m really excited about it. It’s the first thing that I’ve done that has percussion. It has a much bigger, much different sound than what I’ve done before, and I really do feel like it’s some of my finest work, so I’m excited for it to see the light of day. I started work on it in the summer of 2020. So it took me about a year to get it all together, the longest I’ve ever invested in a project, and so, so worth it.

I hear you on studios closing. We’ve gone to completely remote producing for Afropop Worldwide, and I’ve set up a home studio for my own music. Studios may have a hard time getting customers back now that we’ve all learned to do things ourselves. But back to the African connection, let’s talk a little bit about Anansi the spider, the precursor of Brer Rabbit. How did that become the theme of this album?

I grew up hearing stories about Anansi and Brer Rabbit. I’m not entirely sure why, but somehow it happened all the time in my school library. It may have been just one of the cool, D.C. child things, because the city was majority Black. Might still be, but we’re losing it. But I got exposed to all sorts of things that I now realize are kind of like niche Black culture, like step dance groups. All this stuff that I thought everyone had, and now I talk to people and they’re like, “I have no idea what you’re talking about.” It was so jarring when I got into old-time music and then I said “step dancing,” and someone thought I meant Irish step. “No, that’s like Riverdance. That’s a different thing.” It was fascinating.

But Anansy and Brer Rabbit were definitely part of that. I remember being a kid in kindergarten and first grade and hearing those stories. Storytellers would come through and present at the library or whatever. The thing for me that tied it all together was feeling like these “spider tales,” these Anansi stories, were things that traveled kind of in the same way that the music did. I'm always trying to find useful parallels that I can use to explain to people the lineage of the music, because I think a lot of people don't really get how music can be passed down without staying exactly the same. We’re so used to learning all of the stuff that our parents knew when they were kids from exactly the same recordings they were listening to as kids. It's hard for us to think that if we didn't have the records to play, Beatles songs would sound totally different now than they did when they wrote them.

So I was trying to think about how I could adequately illustrate to people what it means for these songs and these tunes to have come from Africa, even indirectly, even if they've changed after getting here. I thought that the spider tales were an easy, concrete example, which again may not be something everybody knows about, but I think it's much more familiar for us to say, “Yeah, this is the telephone game.” The story came over. Characters changed. Language changed. But the story serves the same purpose; the same stories are being told. I wanted to tie the songs to that, to make it clear that, in the same way, the musical language has changed. Some of the concepts have changed, but the music is doing the same thing. To me that's an interesting thing.

You know, the last time I was in Mali, I was doing some research about banjo roots. And I played John Tyree’s “Fox Chase,” from the Black Banjo Songsters album for one of the top ngoni players, Bassekou Kouyate. And he immediately started playing along with it and said, "I know this song.”

That is so cool.

He claimed that it was this very old song, “Njaro,” which goes back centuries and that his father used to play. You never know how to seriously to take things when someone is that literal. But the fact that he could play along with that song, which is very odd and tricky, was persuasive.

That tune is kind of impenetrable. So that's very cool.

Well, Malian ngoni music can also be somewhat impenetrable. On another subject, in your concert you referred to the website Country Queer, which I had never heard of. I checked it out. It’s very interesting that you’ve chosen to make queerness a part of your professional identity. I imagine that could be somewhat controversial in old-time circles, perhaps even more so in African music circles. Talk about that decision.

It's funny. I've been thinking about that a lot lately because I've been working with more and more African sounds, and I always wanted to go there. And I'm feeling like because I've made this such a public part of my image, of my brand, that I can't. There's not a safe way to do it, and it breaks my heart a little bit because so much of that fear came from here. It's American evangelicals who were going into Africa and pushing this terrible legislation through.

So true. The familiar line is that Westerners introduced homosexuality to Africa, whereas in fact what we introduced was homophobia.

Exactly. The funny part is that that specific evangelical crowd is not very present in old-time music. Old-time music got totally hipified in the ‘60s and ‘70s. There have been a lot of lesbians playing old-time music for a long time, though not as many out men playing old-time music.

I could see that on the Country Queer site.

Country Queer is casting a wider net than just old-time music, because they’re doing commercial country music. They're doing folk music. They're doing blues. It's more like Americana queer. And I love that they're doing that. I think it's really important. When I was learning, I had a number of established mentors who were out. Cathy Fink and Marcy Marker are legends, and there’s Debra Clifford and Becca Wintle. There are tons of people out there who were playing, and I never felt like I was being mistreated or anything like that.

Now if I was going to a very different fiddlers conventions, I might have a different experience. There are definitely ones I've gone to where I have not said anything to anybody and where I wouldn't say anything to anybody. But I tend to think that the more religious conservative, homophobic types tends to play bluegrass rather than old-time, which is an interesting distinction, and of course not a clear line, even between what is bluegrass and what is old-time, let alone who plays which. But there are conservative home-school family bands in bluegrass music, where eight children will all get trotted out in matching outfits out of the 1920s. There's clearly a thing they're trying to convey. That thing I stay clear of. And I know I have queer friends who grew up in bluegrass music and at much closer proximity to that and got a lot of s#$% from those folks. So I know it exists.

But I've had a pretty good time, and I'm fortunate to have a team and a record label who understand that it's important for me to be out, and have unequivocally supported me in that.

I would just say to you about going to Africa that you shouldn’t rule it out. In general, people don't ask about that stuff. And when you're dealing with musicians on a musician-to-musician level, other differences tend to melt away. I think you would actually be very well-received in a lot of African music situations, especially given your talent. Maybe you’ll have added incentive after you get this next Africa-influenced album out. When you think that will be, by the way?

I would conjecture quarter three or quarter four of 2022. I'll let you know.

Please do. It's a pleasure to speak with you.

You too. Thanks for taking the time.

Related Audio Programs