Blog September 28, 2015

James Germain: Kreol Mandingue

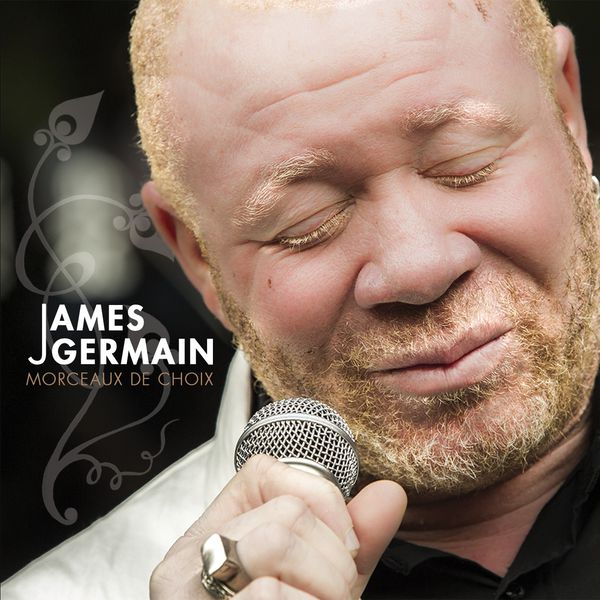

James Germain might be the most important Haitian singer today. It is not only because he was born and raised in St. Antoine, a Port au Prince neighborhood that is famous because of its stance against the criminal Duvalier regime's repressive culture. It is also not only because he came of age during the years of the very public upheaval of the Duvalier dictatorships, and has carried the hope throughout his musical career that Haiti can become beautiful again. It’s that he is all of those things while being a classically trained musician. Not only has he received classical training in Haiti, he also studied music in Paris at the Conservatoire Claude Debussy and l’Ecole de Jazz du Centre d’Initiation Musicale. His artistic project is the replenishing of the Haitian spirit through art by singing modern versions of traditional Haitian songs, for the most part Vodou spirituals, but also complaintes, songs that complain about the situation in which a certain person is living. He has done this through three albums so far, Kafou Minwi, Assoto, Kreol Mandingue, and an anthology of his songs, Morceaux de Choix, which are all on Spotify. “Latibonit,” on his first album, Kafou Minwi, is a great example of a complainte that he makes into a modern song. The song, sung in the first person, tells the inhabitants of Latibonit that he heard that Sole was in bed and dying and that when he got to Sole she had already died; that it hurts him to have to bury Sole.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oaNhABMdDRs[/embed]

Haitians tend to love to be in groups and in crowds. Haitian popular culture is mostly a product of its coumbites (work collectives), mass political struggle, and religious ceremonies. Traditional rhythms that are popular are key because of this. In Haitian culture, traditional rhythms are often sacred, and each region of the country has its traditional rhythms. Germain's native city of Port au Prince is associated with the Erzulie spirits, or loas, and they dance kongos, the rhythm of love, but also petro, the rhythm of war, and to rada, or what remains of the rhythms of the Arada tribe members transplanted to the New World. Throughout his three albums, James Germain excels at singing all that his city’s patron spirits love. He also sings other rhythms that Port au Prince loves well such as the nago, which descends from the rhythms of the liberty-loving Nago tribe.

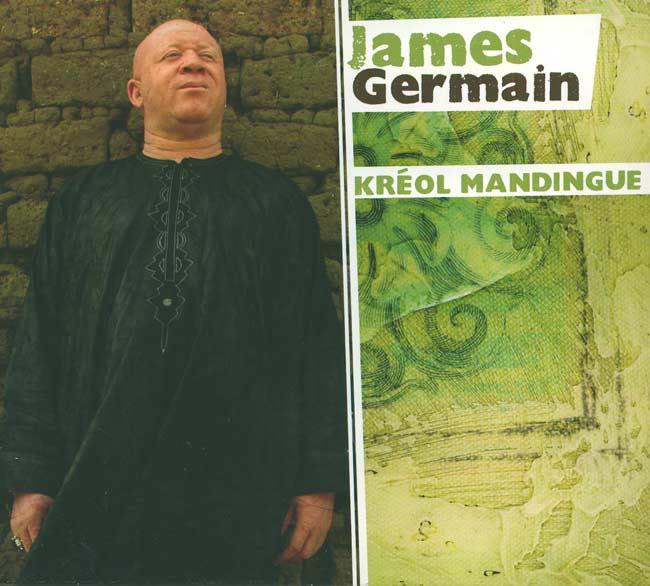

Perhaps Germain’s greatest achievement is the album Kreol Mandingue. In 2007, the singer fell in love with Mali on his second visit to the African continent, while working with a choreographer Kettly Noel on her show Chez Rosette and decided to stay. For three years, he was immersed in Malian life and though he found it atrocious that albinos like himself were being persecuted (the singer Salif Keita, also an albino, has a foundation that tackles the issue head-on that he congratulates), he told me in conversation that living in the country was "the meaning of life itself." The album combines Malian traditional rhythms and Haitian lyrics for a superb rendezvous with his past. In Haitian kreyol, a language created by both colonial masters and slaves that most Africans do not know, he sings to the Yoruba-descended Haitian loa Ogou, complaintes from his homeland, and to the Lenglesou, a dangerous spirit not of Yoruba descent, on an African rhythm unfamiliar to Haitians. He thus bridges factors of tribe, race and nation that often turn into war between us. In Kreol Mandingue, he steps out of his comfort zone to make what he believes is the most human version of art: music that comes from mind-changing travel.

James Germain explained to me that his biggest obstacle is resources. It is hard for a musician with his ambition to make such music. Haiti has issues preserving its heritage. Years of pushing Haitian popular culture aside in order to copy European culture has done a lot of damage to the country’s heritage. He is hired by the Haitian government to sing at official functions, he performs often, and his albums have been released by French record labels but, unlike many European musicians, he is going at this almost alone. However, he remains optimistic. He plans to continue to explore Haitian musical traditions with the highest level of artistry, regardless of what it takes.

Perhaps Germain’s greatest achievement is the album Kreol Mandingue. In 2007, the singer fell in love with Mali on his second visit to the African continent, while working with a choreographer Kettly Noel on her show Chez Rosette and decided to stay. For three years, he was immersed in Malian life and though he found it atrocious that albinos like himself were being persecuted (the singer Salif Keita, also an albino, has a foundation that tackles the issue head-on that he congratulates), he told me in conversation that living in the country was "the meaning of life itself." The album combines Malian traditional rhythms and Haitian lyrics for a superb rendezvous with his past. In Haitian kreyol, a language created by both colonial masters and slaves that most Africans do not know, he sings to the Yoruba-descended Haitian loa Ogou, complaintes from his homeland, and to the Lenglesou, a dangerous spirit not of Yoruba descent, on an African rhythm unfamiliar to Haitians. He thus bridges factors of tribe, race and nation that often turn into war between us. In Kreol Mandingue, he steps out of his comfort zone to make what he believes is the most human version of art: music that comes from mind-changing travel.

James Germain explained to me that his biggest obstacle is resources. It is hard for a musician with his ambition to make such music. Haiti has issues preserving its heritage. Years of pushing Haitian popular culture aside in order to copy European culture has done a lot of damage to the country’s heritage. He is hired by the Haitian government to sing at official functions, he performs often, and his albums have been released by French record labels but, unlike many European musicians, he is going at this almost alone. However, he remains optimistic. He plans to continue to explore Haitian musical traditions with the highest level of artistry, regardless of what it takes.

Perhaps Germain’s greatest achievement is the album Kreol Mandingue. In 2007, the singer fell in love with Mali on his second visit to the African continent, while working with a choreographer Kettly Noel on her show Chez Rosette and decided to stay. For three years, he was immersed in Malian life and though he found it atrocious that albinos like himself were being persecuted (the singer Salif Keita, also an albino, has a foundation that tackles the issue head-on that he congratulates), he told me in conversation that living in the country was "the meaning of life itself." The album combines Malian traditional rhythms and Haitian lyrics for a superb rendezvous with his past. In Haitian kreyol, a language created by both colonial masters and slaves that most Africans do not know, he sings to the Yoruba-descended Haitian loa Ogou, complaintes from his homeland, and to the Lenglesou, a dangerous spirit not of Yoruba descent, on an African rhythm unfamiliar to Haitians. He thus bridges factors of tribe, race and nation that often turn into war between us. In Kreol Mandingue, he steps out of his comfort zone to make what he believes is the most human version of art: music that comes from mind-changing travel.

James Germain explained to me that his biggest obstacle is resources. It is hard for a musician with his ambition to make such music. Haiti has issues preserving its heritage. Years of pushing Haitian popular culture aside in order to copy European culture has done a lot of damage to the country’s heritage. He is hired by the Haitian government to sing at official functions, he performs often, and his albums have been released by French record labels but, unlike many European musicians, he is going at this almost alone. However, he remains optimistic. He plans to continue to explore Haitian musical traditions with the highest level of artistry, regardless of what it takes.

Perhaps Germain’s greatest achievement is the album Kreol Mandingue. In 2007, the singer fell in love with Mali on his second visit to the African continent, while working with a choreographer Kettly Noel on her show Chez Rosette and decided to stay. For three years, he was immersed in Malian life and though he found it atrocious that albinos like himself were being persecuted (the singer Salif Keita, also an albino, has a foundation that tackles the issue head-on that he congratulates), he told me in conversation that living in the country was "the meaning of life itself." The album combines Malian traditional rhythms and Haitian lyrics for a superb rendezvous with his past. In Haitian kreyol, a language created by both colonial masters and slaves that most Africans do not know, he sings to the Yoruba-descended Haitian loa Ogou, complaintes from his homeland, and to the Lenglesou, a dangerous spirit not of Yoruba descent, on an African rhythm unfamiliar to Haitians. He thus bridges factors of tribe, race and nation that often turn into war between us. In Kreol Mandingue, he steps out of his comfort zone to make what he believes is the most human version of art: music that comes from mind-changing travel.

James Germain explained to me that his biggest obstacle is resources. It is hard for a musician with his ambition to make such music. Haiti has issues preserving its heritage. Years of pushing Haitian popular culture aside in order to copy European culture has done a lot of damage to the country’s heritage. He is hired by the Haitian government to sing at official functions, he performs often, and his albums have been released by French record labels but, unlike many European musicians, he is going at this almost alone. However, he remains optimistic. He plans to continue to explore Haitian musical traditions with the highest level of artistry, regardless of what it takes.