Afropop first met Johnny Clegg at his house in Johannesburg at the end of 1987, almost a year before our program first went on the air. For me, on my first trip to Africa, it was a great moment, as I had been listening to recordings of the band Juluka for a few years by then, and as a guitarist, I was especially taken with the unique Zulu finger-style guitar playing in the songs. As we sat and talked, I came to realize that Johnny was a brilliant raconteur with a penetrating sense of South Africa’s complex history and culture, and he also had a keen finger on the pulse of a nation that was on the verge of radical change. Remember, apartheid was still the law of the land, and clinging fiercely to power.

Over the years, we’ve had many occasions to see Johnny’s spellbinding performances with three different bands. And we’ve had many conversations about the changes in music, politics, cultural life and so much more, both in South Africa and around the world. Johnny has always shown that same clear focus, passion and articulateness that he shared with Sean Barlow and me on that first meeting.

So it was poignant indeed to learn that Johnny is now fighting pancreatic cancer. At present, while the cancer is in remission, he has decided to embark on a worldwide tour titled The Final Journey (tour dates here). We met at the NPR bureau in New York on Oct. 12, 2017, in advance of Johnny’s New York shows at B.B. King Blues Club on Oct. 23 and 24. Here’s our conversation.

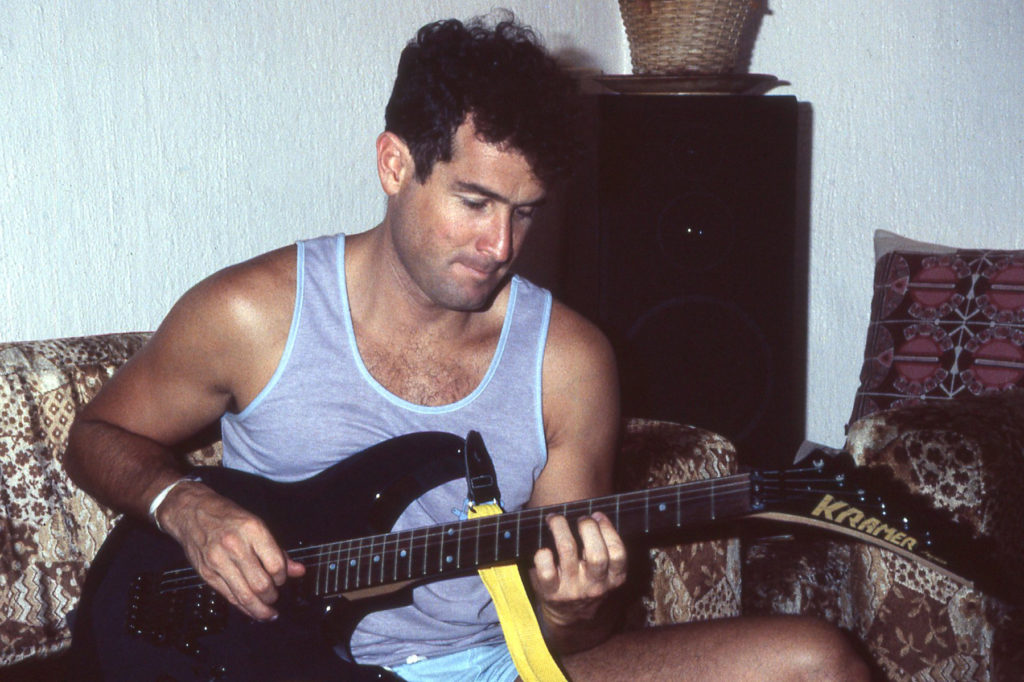

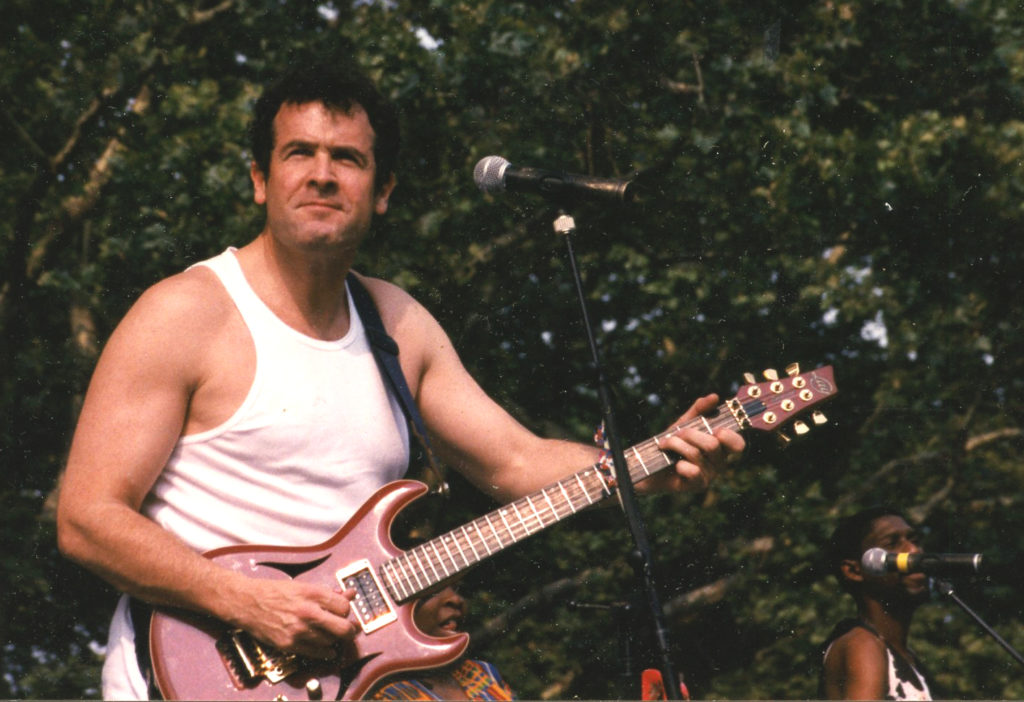

Johnny Clegg at home in Joburg (Eyre 1987)

Banning Eyre: Well, Johnny, good to see you. I guess we should start by talking about your situation and what inspired this tour.

I was diagnosed with cancer in 2015. I had an operation. I went into chemo for six months, and then I went on tour in 2015, did a two-month tour of America and Canada. Some European dates. And then, it flared up again, and I had to go back into chemo in August of last year, and I came out in February of this year. And now I’m in remission. So I just spoke to my management said, “Look, you know, I don’t know. This is a bit of a ping-pong, up-and-down situation. I would rather, while I am still strong, fit enough, basically wrap up my affairs and hang up my boots, but do a world tour. A final journey.”

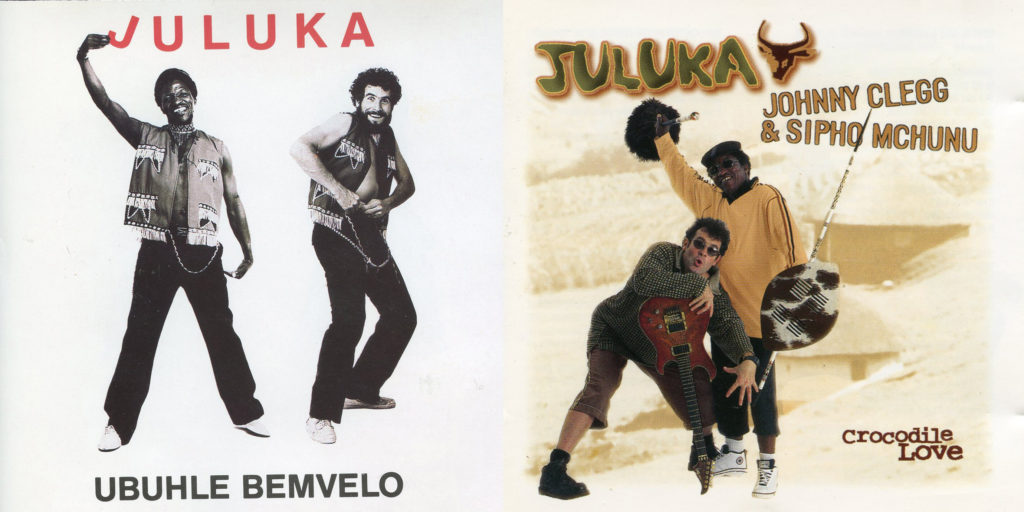

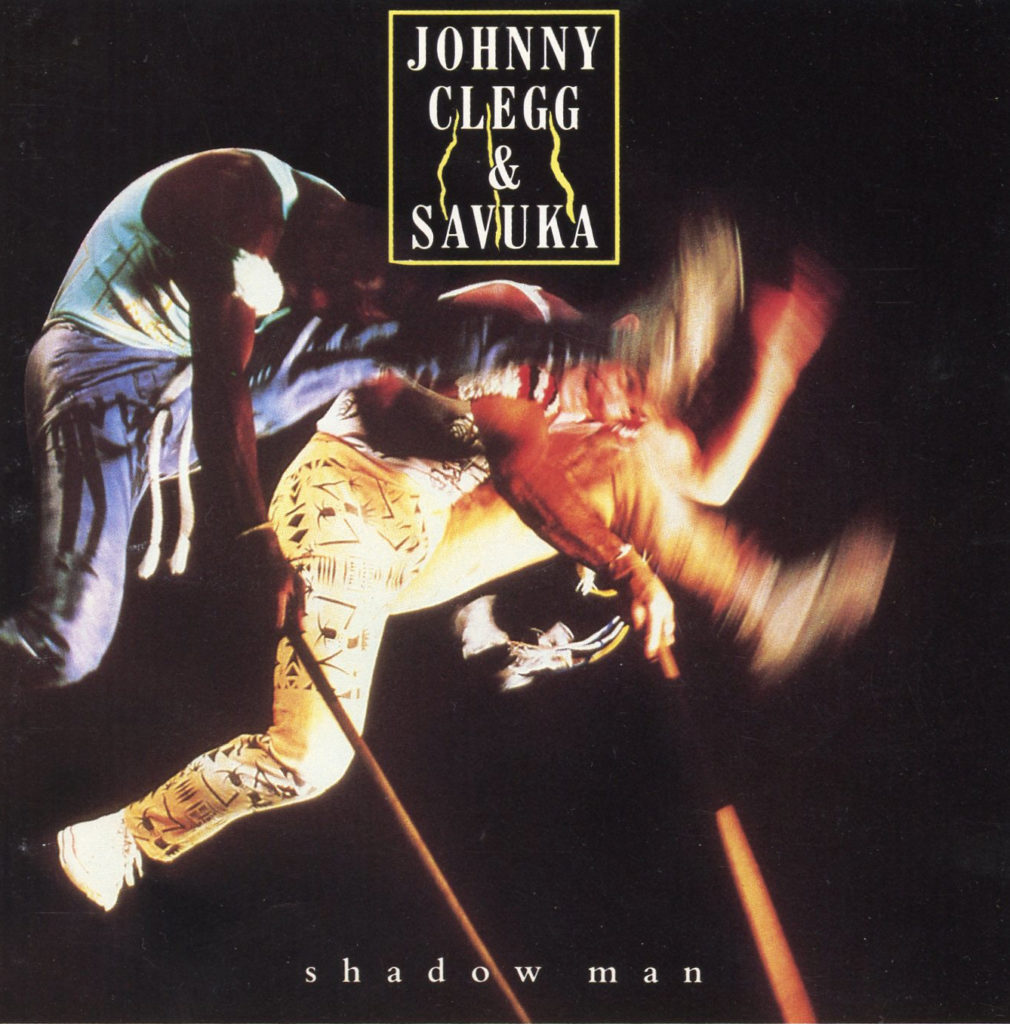

It’s a concert that is autobiographical, audiovisual, some videos and other footage. Storytelling. But also songs selected over the four decades that I identify in my musical career. The first is the Johnny and Sipho [Mchunu] period, which is 1969 to about 1977. And then the Juluka period, which is 1979 until 1985. And then the Johnny Clegg and Savuka period from 1986 to 1994. And then the Johnny Clegg three or four albums that I did after that on my own. There is one exception, which is in 1996, I phoned Sipho and said, “You know what? We’ve got seven albums in the old South Africa. Let’s just do one new one in the new South Africa.” So we recorded that album and toured it for a year. So that was like a hangover from Juluka. And it did pretty well for us. We were very happy with the results.

Juluka, 1976 and 1997

Now, embarking on this tour, I’m busy writing an autobiography. I have just finished a studio album. And I have also got a live recording of this show, which I did in Johannesburg, of The Final Journey, which will be basically the life story, some of the stories and anecdotes as part of the collection. So it’s basically taking me back to the very early days of Pete Seeger, when he did his worldwide music album [Folk Music of the World, late 1950s], and I listened to it when I was 13 or 14. He told stories about this Russian song, or this German song that he had recorded. These were folk songs from all over the world. And I was intrigued. It was the first time that I heard someone singing in the language of that particular folk music tradition, and I thought that was very brave, and a very instructive manual for me when I started my Zulu music journey and adventure.

Seeger was an important and iconic folk singer. And more, he was a communicator. He communicated through folk music the aspirations of the people that he was singing about or talking about, whether it’s love songs, trade union songs, songs of war, songs of yearning. Whatever it was. And Woody Guthrie, obviously. The whole, early, early ’60s hard-core folk music. Music of people that’s passed down in the working class from generation to generation. So this album that I want to do, the live one, is autobiographical. So I have stories. It’s similar to the Irish folk band who did a very famous concert at Carnegie Hall.

Not the Chieftains.

Not the Chieftains. But they had these wonderful stories in between the songs. It was beautiful.

Well, that’s always been such a great feature of your performances, your narratives.

Yes. I’m looking forward to getting that out. That’s being mixed at the moment. But the recorded album is now signed to Universal for the world. We did the signing two weeks ago. It should be out in digital in the next week, and the album, probably as a CD—if people still collect CDs—will be released in two weeks time, and obviously on sale at our shows in America.

And this is new material. I’m interested in how any person receiving the kind of news you have would respond to it. Your response is impressive, great. But I’m curious about the songwriting side of it, because you wrote these song during this difficult time.

I wrote these songs in March this year. I hadn’t been in the studio to write new material for 10 years. My French management phoned me and said, “Look, there’s a guy who wants to do an animated movie, and he wants music. He loves Johnny Clegg, and he wants to have an organic, sort of environmentally friendly music, and he thinks of you all the time. Would you just put together some sounds for him? Traditional sounds. Concertina. Mouth bow. Zulu guitar. Mbira dzavadzimu.” And so I said, “Well, instead of sending him little discrete things, I’m going to put a two-minute song together with all my capabilities in different parts of the song.” And I did.

The project there fell apart, but my juices got going, so I thought, “I’m going to stay in the studio.” My son Jesse and a young producer got together with me and they said, “Look. We know you normally come in the studio and write an album. We want to force you to write singles. You’ve never written singles in your life. We want you to be able to get to a younger market. And we want you to be able to look at mixing the new pop sensibilities with your various Zulu and other influences.” And it became a very interesting project for me, because these are young guys. They are young and hungry. And it’s much harder for them to break into the music scene, and to be aware of all the platforms, and all the various formats.

So, for instance, I had a very long verse coming into one song, and this young producer just said, “Cut this out. That’s a great poem. Keep this. The first top 20 records around the world come into their choruses in 25 seconds. So let’s try and be a bit disciplined about our songwriting and not waffle on and carry on.” And my son was really strict with me. So I had these outside influences, guiding me, saying, “Look, this is a great concertina line, and this is a great Zulu chant. Let’s put it into a more universal context.” And we had long arguments. The thing that I liked was the instrumentation was kept, the bass line, etc. These were maintained, but they would then say, “O.K., let’s keep the line, the melody of this plucked thing on your guitar, but we’re going to put in a more modern sound.” So it came out of a Zulu picked line, but it’s now electric piano through a reverse hyped-up speaker with… I don’t know. All that stuff.

Look. It’s a brave new world. I’m pretty happy with it. The content of the songs is very much a Johnny Clegg content. We are going through a very crazy period in South Africa. Massive looting by the government of state resources. The use of race now in order to isolate white businesses and corporations. And race becoming an issue again after 20 years in South Africa. And so I wrote a song called “Color of My Skin,” talking directly to those things. So I’m still reflecting on my country, on issues that I think are deeply ironic, and also speaking to some universal moments that are happening around the world.

I think we are moving into a kind of massive, global meltdown of national identities into sub-identities. The fracturing of societies on race, class, gender, and politicians making hay while the sun shines. And the global elites not really worried about anything, because they are not aligned to anyone or anything except their bank accounts. So it’s a very, very wobbly time globally, and South Africa is part of all this. You are seeing that global perspective, but refracted through the South African interpretation. I have a few love songs, and I have a song called “Ocean Earth.” This is about the perilous nature of our environmental situation. And then I collaborated on a song with my son Jesse on a very personal song called “I’ve Been Looking.” It’s about having to make a left turn in your life [long pause] and deal with it.

Johnny Clegg on mouthbow, B.B. King, 2016

Wow. This sounds like a fitting cap to your enormous body of work. Considering what you are facing, I find it amazing to see this outpouring of creativity. I’m very moved by that. When you look back, in doing this autobiographical work, is there a time that stands out?. You have lived through so much change, so much history. I remember first meeting you in Johannesburg when apartheid was still on. You already had so many stories to tell. But is there a period that stands out especially?

Yeah. It was the early days, when I met Charlie Mzila in 1967 when I was 14 years old. I was learning classical Spanish guitar and my mom was a jazz singer, cabaret singer, my stepfather was a journalist and crime reporter. And I met the street musician outside a café one night. I had gone to get bread and milk, and I noticed the guitar was tuned differently, and played differently, without any chords. I thought it was amazing. And something made me understand that this was a unique genre of guitar music, indigenous to South Africa, much like the blues is to America. And I asked him to teach me. And this began my great big, fantastic adventure as a young boy, being taken by him into the migrant hostels around Johannesburg, getting into trouble, ducking and diving from the police.

For me, it wasn’t a political act. I was in love with the music and the culture and the robust resilience of the Zulu migrant laborers who were treated so badly, and with such disdain by the authorities, putting them into market labor hostels in Johannesburg, which were like military barracks—20 beds in the room, open-plan showers. If you came from the rural areas, you had to get a bed number. If you got a bed, you could get a job. It was like this Catch-22. You couldn’t get a bed if you didn’t have a job offer. If you got a job offer, and you couldn’t get a bed, you couldn’t keep the job. Because you had to find a place to stay that was legal, otherwise you’d be arrested for being illegally in Johannesburg.

It was a tough existence. And these Zulu warriors, they fought their way through this and I admired their pique. And then of course when I discovered the Zulu war dancing, that was my conversion. It was the final realization that these people knew something about being a man. These traditional rural men, warriors, their bodies were wired and coded to carry these messages of masculinity and warrior values, which my culture didn’t have. And I was deeply desirous of being able to speak that language the way they did physically in a dance.

You kick your leg high in the air and you stamp the ground, and when you stamp the ground you are delivering a blow to your enemy, or receiving a blow, and then you have a comeback. How would you respond to receiving a blow? But all of this is done within an aesthetic of choosing where to place each blow within the rhythm of the clapping hands, or the drums. So you would place each kick and stamp—two fast ones, two medium ones, one on the onbeat, one on the offbeat—as you did this little psychodrama that you are creating in front of everybody, making it up, so it’s huge pressure on you. And you are competing with another young man who’s making the same claims and statements in front of the same audience. I just found that amazing.

Johnny Clegg Band, City Winery NYC, 2014

So for you, 14 years old, white kid, being ushered into all that, the language, the guitar playing, the dance. I can see how that would top anything.

Those were the golden years. Those were the golden years, man.

Fantastic. And then you’ve done so much with it. I know that over the years, you’ve spoken of your hopes not being fulfilled in terms of what would happen in South Africa. I remember the struggles over foreign content, and the hungry rush of South African youth into American and other foreign music after apartheid. Last year when we met at B.B. King, you were talking about how it is now. Talk a little bit about now. I was asking about maskanda, Zulu guitar music today.

Yeah. Well. It’s all but dead. It’s been marginalized into a little ghetto. It’s not played much at all. There was a huge outpouring of maskanda musicians, and they sought an audience with the Zulu king. Sipho went with all these other musicians, and they said, “We have a Zulu radio station that is playing American hip-hop, rap, r&b, dance music, and we can’t get our music played in our language.”

They went to the king?

They went to the king. And the king was nonplussed. “I can’t believe this. There must be a reason.” And a long discussion and argument ensued amongst the musicians around this issue, and one of the things was that some of them, including Sipho, said, “We are trapped in a style and a format that belongs to the ’60s and the ’70s and ’80s, and because it was our migrant music, and we played it because we were street musicians, we were not recording artists. We were not making money from music. We were simply expressing our lives through informal musical compositions and one or two of us recorded but it wasn’t a career. The music was never designed to be a commercial product. And then it became commercialized and got a very fixed format, and today, young people are not interested in cattle. They are not interested in the content that we sing about. We are all in our 50s and 60s, we come from that generation. We need to find a way to modernize it, at least in what we are talking about.”

Even if you keep the sound.

Even if you keep the sound. And so this little revolution dissipated into arguments among each other about how to go forward. And nothing was settled. There wasn’t a plan. Now there is a band called Ihashi Limphlophe, which means the White Horse. The White Horse band started to bring in hip-hop rhythms with Zulu guitar, some rap, and doing like a real crossover. And they had moderate success. But young people would say, “Well, let’s see, if I want to listen to hip-hop, I’m going to buy hip-hop. I’m not going to buy White Horse messing around with it. I’m not going to buy White Horse because there was 15 seconds of rapping in it.”

It felt calculated.

Yes. They’re struggling. This is an issue. If you listen to any of the 11 official African language stations, you will find that all of the traditional music is played at 3:00 in the morning, and all the top listening hours, which is drive time, and midday, is all modern international and local copies of international music. So what does this mean? It means that South Africa is going through a massive transformation of worldview and values, and that young people want to take their rightful place in the global youth culture, where they could compete as equals in these various genres of music that are going on. I mean, you can find Korean rap, Korean heavy metal, Japanese hip-hop, it’s just that the language is different. But the music is the same.

So we had kwaito, which was this kind of crossover mixture of English, Afrikaans, Zulu and Sotho, and then into a more melodic version of it. But now it’s just rap and hip-hop. Guys are doing the same movements as rappers anywhere. If you watch the videos, they are trying as hard as possible to be global. They’re trying not to be identified as South African, not to be identified as coming from a particular place, but part of this virtual world of hip-hop and rap and r&b.

It’s a paradox considering what you were saying before about world order breaking down, and dividing into camps, with individual identities reasserting themselves. This is the opposite.

This is the opposite. I think it was 2004, the first time in South Africa when more people were living in urban areas than rural areas. You had a massive influx of people moving into this urban environment, which is a form of localized globalization. It is a mixture of so many things. It’s people trying to find a place, much like here in New York. We’ve got Little Korea, Little Italy, whatever it is. In South Africa, we had not only local peoples, but Nigerians, Congolese, Zimbabweans. And they take over areas in Johannesburg and other parts of South Africa as a community. And they bring their taste.

I think you always have an under-the-radar traditional soukous or highlife or Zimbabwean, or Zulu maskanda. There is always a layer of that, but you will not make a living doing that. And that’s the problem. The other problem is that from the top down, from the record companies, promoters, management, and agents. The agents say, “Listen, can you rap? Because I can book you all day long if you can rap. A lot of clubs will take you. They’ll give you $5,000 to come and play.” And so people say, “Well, you know, I will hang up my kora and to do something else.”

Johnny Clegg at Central Park Summerstage (Eyre 1996)

You know, Sean and I spent a month in Nigeria this year, and Nigeria as you know is now ruling the roost in terms of the most successful pop music in Africa. But their take on hip-hop does have a level of Nigerian identity and originality, especially in the language, the pidgin English. There’s a lot of humor in it. I personally don’t find it as satisfying as the old juju, fuji and highlife, but it is undeniably powerful. And I wouldn’t say that it’s wholly imitative of America. It does have a Nigerian imprint, which is part of the reason it’s as successful as it is. Of course, these artists are motivated by the desire to get corporate sponsorship, so there’s very little incentive to be political. They’ve taken the name Afrobeats, honoring Fela, but they wouldn’t touch the kinds of messages Fela had, because that would be biting the hand that feeds them.

Absolutely. And they wouldn’t do it in the same musical format that Fela did it. I think that Salif Keita said it best when he said every generation has to betray the generation that came before it. He said that when he started with his music, singing as a griot, he was attacked. People said you are despoiling and bastardizing this traditional music into something else, using brass and modern instruments. And he spoke about that, very, very coherently. So that is our job as the youth, to challenge the forefathers, because if it is not supplying a universal window on my life as a young man, that I can look through and see the future, then I don’t want it. And I’ll take it and change it, and I’ll open a window for myself.

And Salif did that.

He did that.

He was in town just a month or so ago. I told him about your situation. He was very moved by that. He’s a big fan of yours.

He’s a great artist.

I love that guy. But he was talking about the way it is now in Mali. You know the griots themselves are being threatened by Islamic fundamentalism. There are singers now taking the jobs of griots, singing at weddings, and so on. They sing very similar music, but instead of talking about heroes of the Malian Empire, they’re talking about the history of Islam, Mecca and Mohamed. Salif was alarmed by this. But going to your point about generations, he also said, “Our generation is through. We can’t make a difference anymore. We are corrupted and ruined. The only hope this world has is the youth.”

The next generation. Yes. So, from an anthropological perspective, I think one has to understand that these are the forces of social change. That doesn’t stop. It’s like wave after wave, coming from the ocean onto the beach, and changing the shape of the shoreline. And that’s how generations and societies and social organizations work. We are living in a time of the permanent present. We’re locked into not even talking about where we came from. We’re locked into the next app, the next SMS, the next hit, the next new thing. You know, whether you are on Twitter or Facebook or whatever platform, artists have to rely on these things. They have to capture your imagination now. You have to be relevant in the now. And this makes the environment very, very fleeting…

…ephemeral…

Ephemeral. There is no anchor in anything. And a lot of people play music the history of which they have no idea. It’s so hard. They don’t even know what their own influences are. Now, that may not be a bad thing. It’s hard for me to know, but as I’ve gotten older, I have actually realized how important the understanding of the continuity of a form or a tradition or mode of expression is. Whether it’s in art or sculpture or music or dance, choreography. There is some amazing choreography. I was looking at Russian Cossack dancing in the end of the 19th century, primitive forms. And it’s all breakdancing. All those moves!

[Laughter] The spinning.

The spinning, all that. It’s incredible. And so the idea of cultural fusion or hybrid isolation, clothing and taking in new things. It’s there. If a human being sees it, he can’t un-see it. It’s in his visual vocabulary. He saw that move. It’s now in his memory, and he goes out and he dances, and suddenly the move comes out. He didn’t think, “I’m going to go a copy that move and make myself famous.” It just happened like that

It’s like an archetype.

Yeah. So we are witnessing massive social transformations in all the developing economies all around the world. South America. Africa. Asia. Asian Pacific. China. You know, these are forces that are just so huge and so anonymous and so impenetrable and inexorable. You know, one has to say, “Well, maybe there will be a rediscovery in 10 years time of some great Zulu guitarist or concertina player, and those notes will come through in some other instrument and it will be there.”

At least it’s all recorded.

It’s all recorded and it’s in the digital archive.

Which kind of brings me to another question I wanted to ask you. Your situation brings you face-to-face with this, but anyone who is getting older and has a sense of history thinks about the time they lived in. You compare it to other times you might have lived in. Or you think about the future and wonder what the next 60 years will be like. So my question is, do you feel fortunate to experience the particular things that you have? Do you have apprehensions about what your kids are going to face? Or do you think, “Man, I wish I’d lived in this or that time?”

I think that having my health condition brought me down to a sense that as much as we want to intellectually structure our experiences and memories, and the time in which we live, there’s a certain amount of randomness in the world—chance events, chance meetings that changed my life. These are part and parcel of any human’s life. So I don’t have regrets. I think I was part of a generation that came out of the Second World War. We’re the children of baby boomers and I’m a baby boomer myself.

We lived through an incredible moment of generous liberal expansiveness. I had a free education. In the ’70s, Americans had free tertiary education, and today students are the bearers of biggest debt in the country. It’s a crazy situation. But we lived through times where society actually tried to deliver on its promises to its citizens. There was a political class that tried, and was held accountable. Today, the political class is just a management committee for the elites of the world, the economic and corporate elites. They are just a front.

The interesting thing about Trump is that he’s trying to say, “I am the real guy. I’m the one that’s going to deliver on my promises. I can’t be bought because I am already part of the economic elite.” And that was his attractiveness to most people. Because I think we’ve all been let down by the political classes, globally. The moneyed classes are unable to deal with issues of transformation or infrastructure, of accountability, of being solid financial management side of people’s taxes etc., etc. So were living through a pretty wobbly time.

Yeah, Trump had a good line. He hasn’t really delivered on it, but it worked.

I’m just saying that’s his appeal. People want that. They want to see an independent political class re-emerge that is not open to any interest whatsoever. And you know, after the war, people were very exhausted by two World Wars. I mean, the world got exhausted. They wanted to create a new world, a new society. There was a certain amount of idealism that came into governance. The British National Health Service was created after that. People had made the supreme sacrifice. Their sons and daughters were slaughtered. Hundred million people killed over the First and Second World Wars. There was a sense of a debt to settle.

And so I grew up in that milieu, and it’s very depressing now and South Africa, 20 years down the line, to be seeing our political elite looting and pillaging and involved in all sorts of corrupt behavior. But also, watching these massive global auditing firms, KP&G, McKinsey, being involved in these corrupt scandals in my country. They are looting and assisting the government. It’s a terrible thing to say. It’s depressing, and nobody cares anymore. So one wonders where it’s going to end.

I don’t fear for my children, but I think they will have a tougher time of it, and maybe they will be better people. Maybe this is part of the ebbing and flowing of the human psyche and the possibilities that human beings bounce around. You know, you find that societies go through a form of cultural and political amnesia. A third generation down no longer knows what its real true political inheritance is, what its true cultural, social inheritance is. They have just been born into the situation. It’s similar to white people being born into apartheid, which was being devised in 1948, and they were born in 1952 and just grew up in it. It was an established system. They had no internal ability to size it up, because it was the system they were born into. And so there is this amnesia. You couldn’t talk to them about the Second World War or the rise of the Nazi phenomenon, or the various acts that were passed after 1933 in Germany, which are similar to the acts passed in South Africa. For them it was like, “What are you talking about?”

So I am very strongly aware of this generational issue that Salif Keita was talking about. And it seems to be a flawed aspect of the way each generation passes on the baton. We fail. And if we try to do it, there’s a resistance from the young generation, who say, “You know, I don’t want this old guy’s baton. I want to make my own baton.” You know what I mean?

Johnny and Banning (Devin @ NPR, 2017)

Sure. And it’s even worse in this fleeting ephemeral culture you’ve been talking about.

Yeah.

So it sounds like you do feel lucky to have lived in this particular time.

Absolutely lucky. We were lucky. But again, it was a random event. I was born in that time, and I used my time the best I could.

And you saw the fall of apartheid. A lot of people could live a long time and never see something like that.

That’s right. I lived through a revolution.

Coming back to this tour, have you got your band with you?

Yes. Andy, and Mandy, the whole team. Same band.

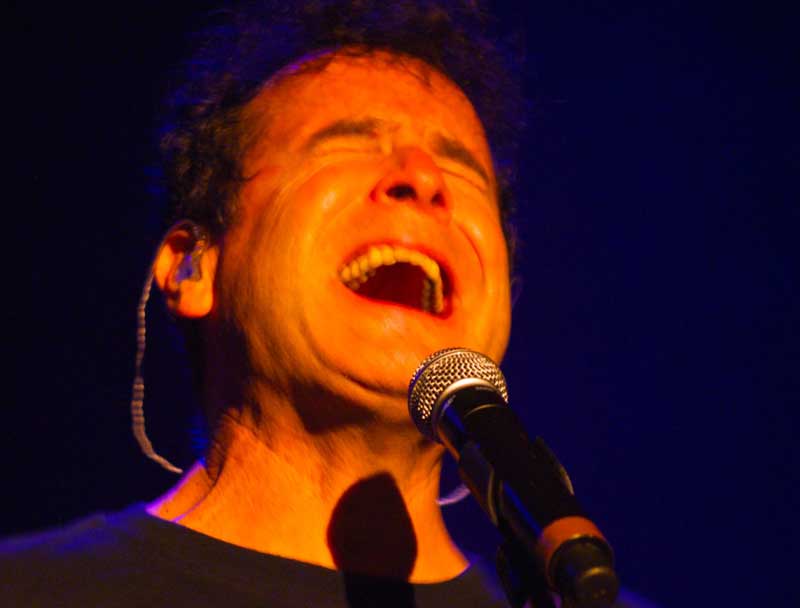

The Johnny Clegg Band, B.B. King (Eyre 2014)

You mentioned Sipho. What is he up to these days?

Well, he did the show with me in South Africa. I didn’t bring him here, but basically we did like three songs, just traditional Zulu songs. Like the old days, just to give people a flavor of the Johnny and Sipho style, which I do perform anyway on my own. But I just thought he was in South Africa, so he played with me some two or three shows there, which was wonderful. Getting him back. And he suddenly discovering… Because he is a very cynical about what’s happened to traditional music.

I’d bet he is.

He is like, “Why do you want to play these songs? Nobody wants to do them anymore.” I said, “No, no, no. They haven’t been played since 1970. That’s 50 years ago. We’re going to play two or three of them, in Zulu, as we used to play them in the street to give them a taste of it, just two minutes of each song. That’s all.” And he was very skeptical. He walked on stage, and I announced his name. Every night, standing ovation. And he was just blown away. It was incredible. Amazing. He was so funny. Because he’s got a great sense of humor. He’s a standup comedian, just very funny. So he made some remarks about me and him. It was a very special, intimate moment.

So he’s well. He has 45 kids, nine lives, lots of cattle. Living the dream!

The Zulu dream.

The Zulu dream!

Good for him. That is fantastic. But he doesn’t ever record anymore.

He stopped recording in the late ’80s. I think he just knows that what he wants to say is no longer relevant to young people. The stuff that he could use, which I draw on a lot, is proverbs and idiomatic expressions from the tradition of the Zulu worldview, which are sometimes very conservative, but also very perceptive statements about human nature.

You know, one often thanks that you’ve got to have a license to drive a car, a license to carry a gun, or to vote. You’ve got a register. You’ve got to do something. But why don’t you have a license for human nature? Because it can be such a dark thing. And so they got a lot of proverbs around these things that are quite funny.

Wise.

Wise yes, which young people don’t get because the Zulu is so classical. People don’t speak like that anymore, and you’ve got to use that classical language. So it affects music. It affects how you can write in that space. So he’s quite cynical about recording and writing.

It sounds like he’s found his way, though.

Yeah. And he will be on the live CD.

I remember seeing you guys as Juluka in Boston, the first time for me. And then there was a time years later when you brought Sipho to Central Park Summerstage.

That was 1997. That was the Juluka album. But I want to alert you and your listeners to the tour we did in 1982 in Germany with Ladysmith. And the Cologne radio there videoed and recorded these sessions. And they are available on CD. And we played about seven or eight traditional Zulu street songs. And they are on YouTube if you go to Google “Johnny and Sipho.”

Those songs are on a World Network CD, you guys and Ladysmith. It’s beautiful stuff. Any other words for our listeners before we go? I imagine some of them would love to see this show but may not get the chance.

Well, you know, it’s been a long journey. And it’s been a life-shaping and a marvelous 40 years for me. I have been fortunate enough to be able to be involved in creating a new hybridization of Western and African music, and finding conversations between different traditions and genres of music, mixing English and Zulu in a time when this was illegal, and a time when it was forbidden. And we managed to get it through, and I managed to get a small career up-and-coming. I am an alternative artist. I was never going to be a Madonna or a Michael Jackson or a Bruce Springsteen. I was much more interested in the cultural aspects of what I was doing, and sharing another world, bringing South Africans into another world of cattle and earth and a traditional worldview, with wisdom that people have passed on through an oral tradition. The stories of their lives.

The wonderful thing about these people is that nobody is anonymous. Everybody has a praise name. And the praise name is your story. It is given to you by your age mates. And the names are not flattering, because they’re looking at your character and your personality and the way you behave in certain ways. It’s funny. They make some really funny statements, but when you die, those names are remembered by your children, and when they call you as an ancestor, and they want to talk to you, they say your names. And so your personal history is acknowledged. Even from a hundred years ago; they remember up to six generations of praise names. I found that just beautiful. I found that so supremely acknowledging and anchoring in the world, that you could live a life where you are just an apartment cleaner, but you are actually also a warrior with a huge amount of history in your praise names, and in the praise poems around you.

And these names are given to you by your age mates, not by any figure of authority.

Yes, your intanga, the people who are your age mates. It’s grouped by roughly seven to 10 years, to form an age regiment. In the warrior society, they created these age regiments, and there were always about seven operating, from the eldest all the way down to the most junior. And these age regiments are called into being by the chief or the king, and he calls them by a certain name. And my age regiment is inala, which is the first green shoots of spring. So I’m inala. My entire group of people between the age of 60 and 70 are inala. I don’t have to worry about Banning. I just say “Inala,” and you say, “Inala,” because we’re in that group. We are one because we share the movement through time and space together as a group.

That’s beautiful. So I imagine you’ve been given a praise name.

Oh yeah. I’ve got lots of praise names. Lots of them. They tend to stick. And you will hear them at weddings mainly, when you perform your imaginary fight with an imaginary foe. You step out into the ring with your sticks and your shield and you demolish your imaginary foe. And they shout your praise names. And of course, I have had some very unfortunate ones, which are quite embarrassing to me. And they shout those; they especially shout those. So, yeah, you know. I have a place. I have a place in the world in my age regiment, with my age mates. I’m dancing now with their sons, who dance with me on stage. They have already retired and they live in rural areas. Their sons call me father, because I’m of their father’s generation. So it’s a wonderful sense of place and, sense of perspective. And one goes through stages of life together, as a group of people.

I must tell you that when I was sick and I got this sickness, I felt far more comfortable telling my age mates that I did my white friends. There was more nourishment in the language, the Zulu language, explaining and talking about it. The idioms. They would say to me, “No, you must carry on. [In Zulu] The ox plows even though it is emaciated. You must carry on plowing.” All these expressions for hard times and difficult things you must overcome. Lots of very hopeful and clever perceptions about adversity, and how one is shaped by adversity, and how adversity has a hidden gift within it, and one must… And they will pepper their discussion with these idioms in proverbs. And I just found it very comforting.

Johny and Mandisa, City Winery, NYC, 2014

That’s beautiful. When I think of all the artists I’ve known all the years of covering African music, your career really stands out. You’ve had so many things going against you. But you persisted and created this incredibly powerful and totally personal expression. Even though it draws on so many different cultures, it’s completely yours. It’s immediately recognizable, and obviously there’s a worldwide audience for it. Maybe it’s not Bruce Springsteen’s audience. But I’ll take it over Bruce any day. Nothing against the man. He’s great. But you take my meaning.

Sure. Sure.

It is been such a pleasure to know you over the years. And Sean and I will be there at B.B. King, with a few close friends.

Thanks, Banning.