Joseph Fahim (who also goes by Joe Kubrick) is the film critic for the Daily News Cairo, an independent, English language newspaper in Egypt. In July, 2011, Banning Eyre and Sean Barlow met with him and his editor Rania El Malky in the newspaper’s office for a wide-ranging conversation. Here is a large portion of that interview, focusing on the history of Egypt’s film industry. This is a compliment to our interview with Moody El Emam, which focuses on the so-called “Golden Era” of the 30s and 40s. Joseph speaks more about developments after Abdel Gamel Nasser came to power in 1952.

B.E.: Cairo has been a film and music production center, one of the first places that films were being made in the Middle East in the early twentieth century. I notice that those films are still showing every day on one of the TV stations available in our hotel room. Can you give our listeners a little bit of a perspective on that history.

J.K.: That's a long story.

B.E.: Well, give us the short version. The highlights.

J.K.: Okay, well, the film industry in Egypt started in the late 1920's, or 1930's, depending on which version you want to believe. But we had the very first film industry in the Middle East and it was essentially established by the hands of foreigners. The very first Egyptian film was directed by two Italian brothers. Most of the owners of the theaters were Greeks, and most of their producers were Jews, and so the Egyptian film industry was founded by foreigners. Of course things changed after Nasser came…

R.H.: In 1952.

J.K.: Exactly. By the way, from the mid-1940's to mid-50s was the Golden Age of Egyptian cinema production, musicals in particular. I think they were on par with the top productions in Hollywood. During that period, our productions were on par with everything that was produced abroad, in terms of entertainment. The quality of it, aesthetically and thematically, that's a different story, in comparison with the French or the Germans of the late 30's. But what happened is, after the 1950's, Egyptian cinema was nationalized. In the beginning of the Nasser era, there was a concentration on religious themes and on nationalistic themes and then you find, again during the beginning of the revolution, all these movies that were essentially propaganda films about the revolution, and criticizing the aristocracy, and it's interesting because that's when the full formation of the censorship started to materialize in Egypt. Before that we had censorship—we always had it from day one—but it changed faces in every regime. For instance in the beginning of cinema, Egyptians were not allowed to criticize the aristocracy or foreigners, foreign nationals, like the English. And then after the revolution, it was almost the opposite. You were encouraged to criticize the aristocracy. You were not allowed to portray them in a good way, and the same thing with foreigners. You were not allowed to show foreigners in a good way during the early years of the revolution.

(Movie Poster for the 1938 film, Yahya el hub)

B.E.: The 1952 revolution.

J.K.: Yeah, exactly. And again, one of the things that Nasser wanted to do was stress the religious identity of Egypt, which was a strategy to combat foreign influence. And it eventually backfired, but again that was like the early 50's, mid 50's, you find the emergence of religious films, which did not appear before.

But again, Egyptian cinema has always been popular, and it attracted all the artists and movie stars from all across the Arab World from Lebanon and Syria and everywhere. Egyptian cinema was founded in Alexandria, which was the biggest cosmopolitan city in the Middle East. When you observe the earlier Egyptian movie you find how liberal they are, how sophisticated they are, and afterwards it still remained like that till the nationalization of the Egyptian cinema and afterwards. From the mid 60's onwards, cinema began to deteriorate and part of the reason is in the Nasser Regime, corruption began to seep into every branch of the industry. Still, we have very prominent movies, but—and I think this happened with the January 25th revolution as well—the optimism you find with the early films of the revolution started to dissipate replaced by more of a realistic look, about the reality of Egyptian society. You'd find that in the films of Salah Abul-Seif; he was the leader of Egyptian neo-realism. And you'd find it the movies of Yusuf Shaheen, you'd find all these allegories that tried to shed different lights on the Nasser regime. And come early 70's, things were turned upside down, you'd find that cynicism started to grow more and musicals started to vanish, you'd find movies with more of an edge to them, with a lot of allegories, because you could not criticize the government back then in a direct way.

Because of the corruption that was happening and everything, and because of the limitations on the freedoms of artists, lots of Egyptian artists, and film makers started to make movies in Lebanon. I think by the mid 70s's, almost the entire Egyptian film industry had moved to Lebanon.

B.E.: Because of this attitude of censorship and corruption…

J.K.: Yes, and also the industry was collapsing economically. I'm talking about late 60's, early 70's when the government went into many productions that cost millions of Egyptian pounds, made no money and were of modest artistic quality.

B.E.: Were they propaganda films?

J.K.: They were nothing really. They were just failed artistic endeavors, that's what I would call them. These productions were mainly a cover up for bleeding more money. By now you can say it was some sort of form of money laundering or something. It was messed up. Interesting thing, during the age of Sadat, this is the one period in history where I'm still trying to figure out what has happened to Egyptian society. I think in the 70's, almost for the entire decade of the 70's, cinema started to be very, extremely liberal, too liberal almost. And you'd find all their movie were relying on the selling point. The bikinis. The bikinis and sex, and if you see these movies uncensored now, you'd be astonished at how frank they are in some of these movies. I'm still trying to figure out why did it happen, how did it happen?

Egyptian society, before that, we still maintained this… we were moderates and you'd find, for instance, drinking was portrayed very casually on screen, unlike now. Same thing with different activities, though there is still an emphasis on certain general morals. The obsession with outwardness that is happening now was not there then. The only movies that were morally or religiously overt was one by this filmmaker—I cannot remember his name—he did this very famous movie called The Sheikh Hassan. Christians were very pissed off—this was during the mid 50's—because it portrayed this sexually transgressive Christian woman who gets married and gets saved by this Muslim man, and her family wanted to convert her but she wouldn't because she loved him because he saved her, and all these movies were very religiously ordered. But anyhow, turning back to the mid 70's, we had like this newfound liberalism. I don't know where it came from, and correct me if I'm wrong, Rania, but during the earlier days of Sadat I think films were….

R.H.: It was all the war movies, right? After 1973, there's a lot of nationalism I think, a lot of film about the war.

J.K.: Nationalism, yes. But I think there was a fair amount of liberty given to the movies, lots of allowances. And so you'd find I think some of the best movies produced in the history of this country were produced in the 70s's, because they started analyzing the Nasser era and they were politically themed. Karnak was in 70's

(scene from Al-Karnak)

R.H.: That was a seminal work, it's based on a novel by Naguib Mafous. Karnak was severely critical of the Nasser Era. Was it made during Nasser?

J.K.: It was made during Sadat. Of the two movies that were made during this era, one was banned and one was not. Shai’ Min El-Khof and Al-asfur. Al-asfur was a very overt allegory about the '67 defeat and the failure of the entire Arab world to unite and that was banned. The other was Shai’ Min El-Khof, by Hussein Kamal and that was one of the seminal works of the entire Egyptian cinema history and it was played a lot a symbolism and allegory and it was basically about a guy

R.H.: The lead character he's this dictator.

J.K.: Yeah, he's the leader of a small village in the south and he rules the village with an iron hand. He's a dictator. And at the end of the movie, the women he covets and desires….

R.H.: He forces her to marry him.

J.K.: Exactly. And she symbolizes Egypt.

R.H.: And she stands up against him and rallies everyone else against him and it's very, very symbolic and it's clear that it was against Nasser.

J.K.: Exactly. And at the conclusion of the movie, they had a very famous scene where the entire village rallies around her to save her and they sing “Gawaz Atriss Men Fouada Batil” [The Marriage of Atriss (lead male character) and Fouada (lead female character)] is illegitimate and that's essentially what the director was trying to say about the marriage between Nasser and Egypt. Interesting thing about it, it was initially censored. And then when Nasser saw it, he said "No I cannot, I have to allow it. If I really am Atriss then I deserve to be abolished.”

R.H.: He really said that?

J.K.: Yeah.

R.H.: Oh I didn't know that story

J.K.: And that's how the movie was screened.

R.H.: So it was screened during his time?

J.K.: Yes, yes, it was. During the last days of Nasser.

B.E.: That's fascinating. And the name of that movie was again?

J.K.: Shai' min Al-Khof, “Some kind of fear.” [alternatively “Something of Fear”] By Hussein Kamal.

B.E.: That's a great title.

R.H.: You should watch this film. Really, it’s incredible.

B.E.: Interesting. I will look for that.

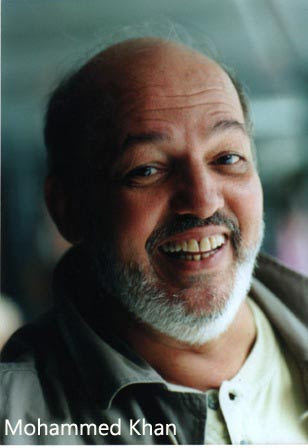

J.K.: What happened afterwards, as I'm saying, in the 70's movies there were films with lots of overt sexuality, overt sexual content, and lots of edgy politics, and then the 80's came and the entire spectrum of the film industry changed. There was no money in the country. We had the open door policy and the entire structure of the industry changed. There were the big companies that had produced all the masterpieces of Egyptian cinema were either bankrupting or going out of business. And so basically at that point Egyptian cinema was relying, as it is now, on the efforts of independent directors. And that eventually led to the rise of one of the most interesting film waves in Egyptian film history, which was a neo-neo-realistic wave by a bunch of pioneers like Atif Al-Tayyib, Muhammad Khan, script writer Bsheer Eddeek, and Dawood Abd El-Said. All these film makers were chronicling the sense of chaos that came about with Sadat's open door policies. They were mostly very grim, shot very realistically, with no budget. They were not as commercially successful, and they were an aberration. They were the exception to the rule. We were swamped with these horrible B-movies, commercial movies. But these were like the rays of light, the few rays of light.

But there were plenty of films because these directors were very active. They matched together, but the quality of their pictures is low. I remember Bsheer Eddeek, the script writer of Atif Al-Tayyib, one of the script writers of the 80's. He was telling me that Atif Al-Tayyib for instance, his lens was always dirty. He didn't care what his images looked like. He just wanted to capture the moment and get it across.

I myself find it difficult to watch the movies of the 80's because not only did they chronicle the beginning of the pitfalls of the open door policies, but also the beginning of the Mubarak era. And they were, as I'm telling you, very grim. They had no sense of salvation to them. And then you find all these changes that have struck Egyptian society were chronicled by these film makers. If you compare the movies of the 70's and 80's, you can tell the huge discrepancy that Egyptian society went through in those few years: the rise of religious conservatism, the sense of chaos, the overpopulation, the increase in poverty, the rise of the Nouveau Riche, which is one of the most obsessive things for these film makers and that was the 80's. By that time, Egyptian industry was at a low point, and it continued during the 90's.

B.E.: Going back to the 70s for a moment, this is the period during which sha’bi music is rising.

J.K.: Exactly.

B.E.: And that’s kind of a parallel story, isn’t it? Interesting, edgy films, and interesting, edgy music...

J.K.: And by the way if you think of it, I think this is where the global culture started to deteriorate everywhere, not just in Egypt. It's understandable in Egypt, but again, looking back at the history of international cinema, the 80's in the worst decade for arts. 70's was the explosion of creativity and 80's is the beginning of the rise of commercialism and everything. In Egypt I think it was a coincidence that we witnessed that, because the global influence was not felt in all art forms in Egypt, but again, you can tell that the quality of art deteriorated massively. And in the beginning of the 90's it was even worse. Movies were very disassociated from society and the emphasis was on the commercial hits. There were a number of aging stars that dominated the film industry. Adel Imam for instance has still amazingly been the biggest film star in Egypt for the past 30 years, he's still going strong up to this very day. Actresses like Nadia El-Gindi and Nabila Ebeid relied heavily on sexuality… but that's a big story. What’s interesting is that the turning point in the modern history of Egyptian cinema is the mid 90's. 1995 Egyptian cinema produced 17 films annually. That was lowest number of movies produced in the entire history of Egyptian cinema, since the 30's, since the beginning. That was the tipping point, the point that signaled the collapse of the film industry

But then, in 1997, was the beginning of the renaissance of Egyptian cinema and the formation of the modern Egyptian film industry. What happened is an interesting thing sociologically. There were two movies, comedies of young stars Ismailia Rayeh Gayy (Isamilia, Coming and Going) Said Rayeh Gayy (Said, Coming and Going). Movies at that point were not making money, people stopped going to the movies by the mid 90's, especially Egyptian movies.

B.E.: Because they were not good.

J.K.: They were awful, awful quality, same aging stars. They were not offering anything new, completely not in touch with Egyptian society.

R.H.: And the theater too. The theaters were in a really bad state. The actual physical spaces were terrible.

J.K.: And kids like me, during that time we were watching American films. I spent like most of the 90's watching American films and, unfortunately, we didn't have the even the luxury that we have now of cultural centers, watching foreign films. We didn't have that. And again, talking about culture, when you see the culture in the 70's and 60's, cultural centers were rife with activitym, especially from the Soviet states. You'd find a week for Polish movies and a week for Czech movies.

B.E.: Tell us more about the 90s.

J.K.: What happened in the mid-90s…. As I was saying, “Isamilia Rayeh Gayy” (Ismailia, Coming and Going), this lowbrow comedy was made by this popular Egyptian singer with no acting skills whatsoever – his name is Mohammed Fouad. He went on to make this movie that was really low budget. This movie just exploded. It made more money than anyone expected. It ushered in the new wave of Egyptian comedy. Basically, comedy became the hot thing. Comedy has always been a popular Egyptian genre, but in the late 90s and early 2000s, comedy single-handedly dominated the entire film industry and everything was turned into comedies.

S.B.: You mean situation comedies?

J.R: Low-brow situational comedies and even action movies. Action movies even had comedy angles. That movie I mentioned had a comedy actor – his name is Mohammed Heneidi –and he went on to make his own movie which was Saidi Fel Gam’a El Amrekeyya (A South Egyptian Goes to the American University in Cairo.) I think Saidi Fel Gam’a El Amrekeyya is one of the highest-grossing movies in Egyptian history. Interestingly, for the late 90s and early 2000s, sociologically, these movies in terms of their politics were a far cry from the movies of the 70s. They were much more conservative in vision, aesthetically and socially. They ushered in what became known as the Cinema Al-Nazifa, which is the “clean cinema.”

B.E: So it’s funny. It’s light, you’ve got pop stars like Mohammed Fouad.

J.K.: By clean cinema, we mean family-friendly cinema. What do we mean? It’s cinema with no sex, but not just no sex, no kisses. For the first time in the history of Egyptian cinema, kissing in movies was an act that was frowned upon.

B.E.: For the first time? And it had been there all along.

J.K.: Yeah, starting from the 30s. I think this perfectly captures the essence of what was going on – of becoming more religiously conservative. And I think aesthetically it reflected the state of standstill that our entire culture was in. All these filmmakers came up with these actors –they’re still the biggest pop stars in Egypt. They keep up this trend. They liked having no kisses in the movies, and abiding by very decent factors. Of course, most of them would hit on the big issue – our relationship with Israel. The more you attack Israel the more they like it, and the more importance you give your movie. These weren’t just comedies; they adopted a message. Of course the message was hollow. It was a desire by the producers to show some social responsibility. From the beginning of the decade until the end of it, the industry was exploding: Egyptian stars began to be paid by the millions. They started to market their movies abroad. Not just in the Gulf cinemas, but on other satellite stations. The Egyptian film industry is an extremely profitable business now.

Another factor that shaped the conservatism of the film industry was the fact that in the 60s and 70s, Egyptian films were exported to Lebanon. Lebanon has always been known for its liberal politics. Afterwards, after the civil war erupted in Lebanon and the region, Egyptian cinema began to divert its markets to Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf. Because of the strong conservative nature of these stations, they began to influence the shape of these movies.

B.E.: Fantastic. Now, bring us up to date because it seems like the 2005 film “The Yacoubian Building,” based on the novel by Alaa Al-Aswany kind of breaks this pattern. Tell us that story.

J.K.: In a nutshell, what sustained this liberal streak, which was inherited from earlier ages, was the others, the filmmakers with a vision, the pioneering filmmakers who started in the 80s. “The Yacoubian Building” was a movie that didn’t take no for an answer. It was very risqué: it had sex scenes in it. Of course, nothing graphic, but it was very controversial. It became the highest grossing movie of the year. A huge number. I don’t think “Yacoubian Building” changed anything. It was part of the entire culture by the way. The culture from the beginning of the decade began to experience some kind of renaissance – not just in cinema but in art and culture and music. The Sawy Culture Center was the first outlet to open up to independent musicians. All these artists began to find a new outlet and there was an audience for that. At the time when the country was starting to open up communications with the West, and the internet became widespread… The generation that did this revolution went to hear these musicians, and see these art exhibits and went to see these movies. It was all part of the renaissance that the entire culture started to experience.

(Scene from The Yacoubian Building)

B.E.: And that paves the way to the revolution that we’re seeing now?

J.K.: In many ways, yes. When you see the films that are pre-revolution, many of them anticipate the events that would happen. A major example: There was a movie called Heyya Fawda (Is It Chaos?) by Youssef Chahine. By the end of the movie – the main character is a low ranking police officer who runs the neighborhood of Shubra with a hand of iron. He abuses everyone. There’s this girl who represents the people of Egypt. Again, always symbolism in Egypt. He goes and rapes her. By the end of the movie the entire neighborhood erupts in anger, storms the police station and create their own sort of revolution.

B.E.: And they kill him?

J.K.: He kills himself in the end. It’s very melodramatic – that’s why I have so many reservations about this movie. Forget what happened to me - that scene was very cathartic. You could tell in the cinema that people liked it. That was his most commercially successful film ever. Independent films began to rise in the mid decade. All these films, these young filmmakers with liberal visions, are accurately portraying the essence of what’s going on in the country. Especially with things like these independent films and documentaries and short films. They were not very aesthetically good, but were very honest. People were hungry for things that not exactly reflected reality but provided them with the reasons to rebel. It wasn’t just film – it was music and art. I think art is more popular now in Egypt than any time since the mid 70s. All the art galleries are bustling with activities. Same thing with the independent music outlets.

S.B: Which are what?

J.K: Sawy definitely, there’s the Robert Theatre, there’s Makan, there’s Geneina. In Alexandria, there the Jesuit Cultural Center, the Biblioteca. At some point you have to meet with the leaders of Geneina and have a coffee. They’re absolutely magnificent. They’ve had a big influence in Arab culture. They started attracting Arab artists. They got the first African artist to perform in Egypt and all the concerts were sold out. Bands from Lebanon would come here and perform. Because the concerts were sold out, they would quickly arrange another concert to get more people. That’s what has happened from the beginning of the decade and was started to be realized in the mid 2000s was a great culture scene. I think the reason why the alternative culture scene prospered big time was because they addressed a need. Hakim and Amr Diab, these big stars – as popular as they are, they’re poppy. They’re nice, but do not reflect the society. And then you have a band like Masar Egbari [an Alexandria rock band] would go and that pours their heart out about the state of hopelessness. Their big song is about a guy who wants to emigrate and doesn’t mind if he goes to wash dishes abroad, just to get out of the country.

S.B.: Do you know the name of the song?

J.K.: No, but I’ll send it to you. Same thing with art by the way. The paper – the thing I’ve been doing for the past 3 or 4 years - we’ve always concentrated on alternative culture. We’re a liberal paper and I always try to encourage liberal art. I’m a liberal critic. I have little tolerance for moralistic religious messages that are shoved down my throat, which is the case with mainstream media. The reason why I’ve always been interested in the alternative culture scene is because they’re operated by very liberal artists who take on the establishment and don’t take no for an answer.

You have to see this movie called Microphone? This was coined “the movie of the revolution.” Maybe you have seen this Iranian movie called “Nobody Knows About Persian Cats.” This movie, Nobody Know about Persian Cats, is about the underground arts scene in Tehran. “Microphone” is similar – it is about the underground arts scene in Alexandria. There are other bands and graffiti artists and rappers and skateboarders. It perfectly captures the essence of this generation: a generation that doesn’t take no for an answer, a generation that knows no defeat, a generation that is angry and doesn’t want to take all this crap anymore. Unfortunately the movie was released on January 25 during the curfew. And it was released in a big number of theatres even though it was an independent movie. But it still did good business. I saw it in Dubai for the first time. Even though there was a curfew, and there were a limited number of cinemas open, those screenings were sold out. I’m very interested in the alternative culture scene. I’m not interested in what’s happening now though. Movies like “Microphone” totally reflect a sense of jubilation. I don’t think that’s the case anymore.

We’ve had our victory. We’ve had the revolution. Blah blah. We’re now living in a time of uncertainty, and I don’t think the art scene is keeping up with that. I’m talking about music, about film, everything. I think they’re very reactionary. They’re shallow. I don’t think they’re as deep as they should be. They’re not taking enough time to digest what’s happening. There’s this sense of jubilation and victory that’s fading away. We’re faced with a more problematic and complex situation that artists have yet to tackle. You have directly after the revolution all these art exhibits crammed with indistinguishable photographs from the revolution. Same thing for music – “We’re defeated Mubarak. We have our victory.” I think what has happened is too big and too complex to react that rapidly to it.

B.E.: You think it’s too soon?

J.K.: I think it’s certainly too soon. Now, with all that’s happening, I don’t think anyone wants to listen to songs about how we had our victory on January 25th. The question is how artists will tackle the next phase. The films that were produced in the last few weeks have been a travesty. They were produced in order to capitalize on the scenes of the revolution, and they plastered some scenes from the revolution at the end of their movies. It felt cheap and exploitative. And they flopped. Nobody went for it. I wrote an article. The biggest hit of the summer was a comedy, a low-brow comedy. Producers were claiming that people stopped going to the movies. What happened this season was what happened in the 90s. People flocked in the 90s to Harry Potter and Transformers and the last Pirates of the Caribbean. They did not go to Egyptian movies. The movie they wanted to go see was a comedy. Why? Because we’re in a time of uncertainty. We’re in the midst of a revolution and in times of turmoil people want to escape. In America during WWII the popular thing was the musicals. In the mid-50s, people were shunning the movies of Fellini and were going for melodramas. The number one movie during the economic crisis was Beverly Hill Chihuahua for God’s sake. Same thing in France. Same thing everywhere. People want an escape now. Lots of films are lined up about the revolution – at least six. Some have to scrap their plans because obviously people are not ready to see movies. It’s too soon. And filmmakers are realizing that people are not as enthusiastic as we thought they were. How will these half a dozen movies materialize? I have no idea, but I’m not that interested. I’m not that excited. Except for one movie. Shall I tell you about it?

B.E.: Yeah. Of course.

J.K.: It’s called R for Revolution. It’s by my favorite independent filmmaker, Ibrahim El Battout, a personal friend. Ibrahim El Battout is the pioneer of independent Egyptian cinema. The movie he’s doing is – he went and shot the movie back where he wanted, he shot the first scene... It’s his first movie with a big star, with Amr Waked. Amr Waked is a prominent star. He has appeared in various international productions – very respected. He appeared in Syriana. He was on HBO, BBC. He has a minor role in the next Spielberg movie Contagion. El Battout asked him, “Look: I want to shoot a movie.” He was in Rotterdam promoting his last movie. When he saw him, he said, “I have a movie. I want to shoot a movie. Do you want to shoot it with me?” Amr Waked since day one has always been very anti-Mubarak, pro-revolution. On January 25th he appeared all over YouTube shouting, “Down with Mubarak! Down with Hosni Mubarak.” They went and shot the last scene of the movie, supposedly the day when Mubarak stepped down in Tahrir. It doesn’t have a happy ending. He says, “I’m not interested in the revolutionaries who died in the revolution. I’m not interested in heroes who went to Tahrir to destroy the government. I’m interested in those who stayed home and why they stayed home.” It’s more complex and doesn’t have a happy ending. It should be sincere.

(Amr Waked)

I believe in him a lot. He’s one of the most interesting filmmakers working today. His movie, Ein Shams was the first independent film in history to have a commercial screening. It opened the doors for Microphone and the director Ahmad Abdalla’s other movie, Heliopolis, for other films to be screened commercially. It signaled the entrance of independent culture into the mainstream. It hasn’t been altogether embraced yet but its infiltrating it.

B.E.: That brings me to my final thought: You just said that cinema and culture created a generation that could bring about this revolution. Right now we’re in a period of uncertainty – What’s the new music going to be like? Or is it too soon to tell?

J.K.: Not just that it’s too soon: People think art and music are going to be more serious. That’s all crap. Pop music will still dominate. Comedies and action movies will still dominate. It always has and it always will.

B.E.: My question is: This generation that is used to the internet and alternative culture, to going to places like Sawy Culture Wheel, especially the urban generation that will be driving the art of the future - Do you think that their leaning on alternative culture and the internet that after this period of uncertainty, do you have an optimism that a new kind of film and music will emerge in the next decade? In a way, the genie has been let out of the bottle and you can’t put it back in no matter what government gets elected and no matter what the censorship board says, and no matter who runs the ministries. There’s just something in the culture that can’t be reversed. Do you think that’s true at all?

J.K.: OK, I have a question for you: After any revolution in the world, you find a sort of artistic renaissance. But afterward, what happens? Again, I have a great example: Spain. I’ve been reading and watching a lot about the Movida Madrileña which is the Madrid art wave that has emerged. Of course, the similarities are very thin between what happened in Madrid and what’s happening here. There, it was an explosion of liberal thought and gay culture, which wouldn’t happen here. Ibrahim El Batout mentioned this in his interview: Egyptians have been watching the same exact movies with the same exact stars done the same exact way for so long that we need years – maybe a decade like you were saying – to change that. Same thing with music. Art, of course, is a different thing. There’s always interesting things happening with art, but art will forever remain an elitist institution. There’s always lots of commercial concentrations that should be taken into consideration. I am excited. I am optimistic but at the same time you have to take into account that the vast majority of Egyptians are uneducated. We’re looking at Cairo, but there is absolutely nothing happening in the countryside and the South. Nothing in the vast majority of Egypt.

Egypt is not just Cairo. For instance, I mentioned when I wrote about Abou-Ghazi’s appointment as Minister of Culture. If he wants to have a good legacy, he can’t just clean up the ministry. He has to start establishing culture hubs in all these governments in the countryside that have been deprived of culture for so long. I think that things have gotten so backward and so conservative because of a lack of culture. I’m optimistic but I’m realistic. It’s not an easy ride. It’s going to take ages. If the Brotherhood will have a say in Parliament, we’re talking about a completely different scenario. What people are talking about is the possible rise of Islamic movies, which Egypt has never witnessed before. There were some Coptic movies, mostly restricted to churches. That never became commercial. The Muslim Brotherhood has talked about doing a film about their founder Hassan Al-Banna. They have lots of money so they’re thinking of entering the film industry. Same thing with music. Again, lots of artists and singers…

S.B.: Music as in terms of Koranic recitation?

J.K.: Not necessarily Koranic recitation. That’s always been there. Maybe getting more conservative. In music, it’s less apparent than cinema. It’s hard to get a total picture. Everything that will happen in Egypt on the social and political level in the next month will necessarily influence culture as well.

S.B.: You keep using the words liberal and conservative. What do you mean by liberal and conservative?

J.K.: My perception of liberal art is art that does not abide by concrete moral standards. It’s especially apparent in cinema. Conservative art is the opposite – it abides by certain moral staples. Why I’m obsessed with this word? Probably because in the past few years I can see in lots of mainstream films that the strong religious messages of some movies was going to be blatant. It was very in-your-face. I could not stand that. That’s what I’m writing about now – the rise of conservative Egyptian film – cinema in the age of Mubarak. I think that art should lead, all art fields should be the leader. They should not necessarily abide by what society wants to see. It should be a reflection of the artists’ ideas. That was not the case in the majority of mainstream Egyptian films. Not just clean cinema in that there’s no kissing scenes, but the tone of the movies: The fact that there’s a clear-cut line between right and wrong; there’s a clear-cut line between immorality and morality; there’s a clear-cut line between obeying God’s orders and disobeying them. You’ll find that trend if you analyze the movies of the past decade. You’ll find that that trend is growing.

B.E.: Thanks so much, Joseph. You’ve taught us a lot.