Record-hunter Tasha Goldberg continues her saga of searching for rare vinyl in Johannesburg, South Africa. Read Part One here.

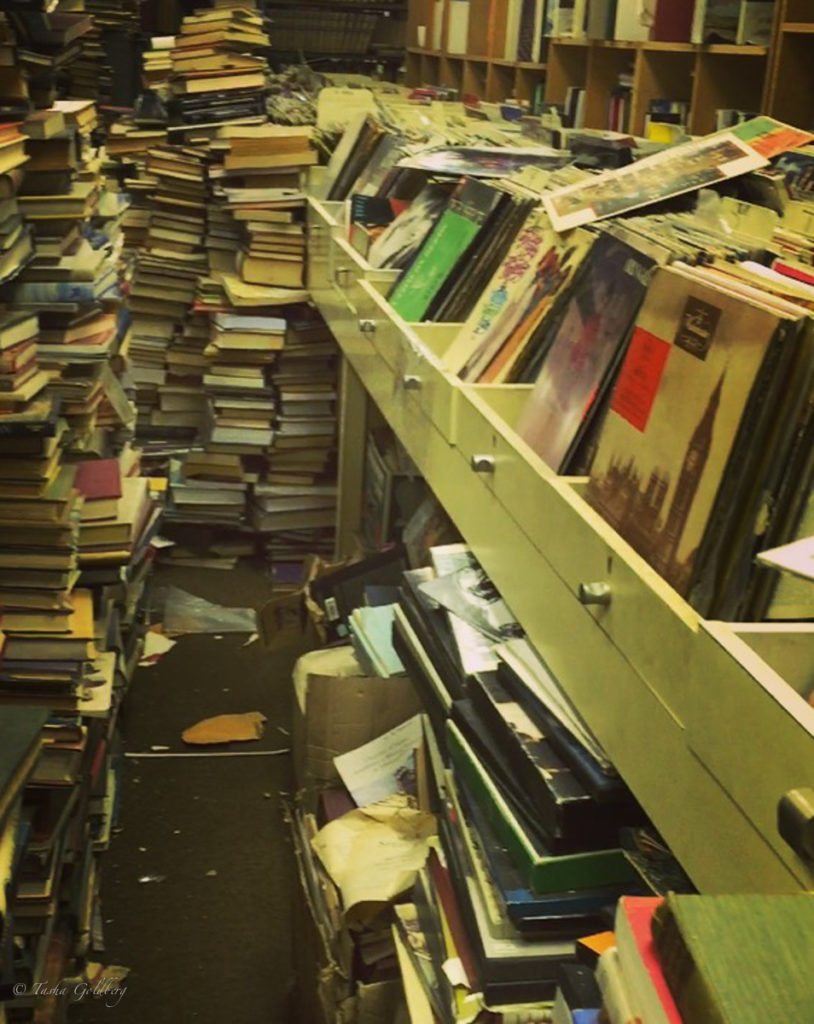

The hours I spent at Collector’s Treasury in Johannesburg, South Africa still mystifies me. Sometimes, when I close my eyes at night, I can still see the walls of books and records lining the rooms of the eight-story warehouse. I can still smell the crowds of vinyl hunched against walls, seemingly spent from years of being on the road. Inside of realm where the only voices are recorded, a place where stories are church, I can still feel the bruises on my knees from the proper posture of a digger. Each slight turn of my head brought me to another place of worship. Traveling through Jozi introduced me to nations and generations, all with the drop of a needle.

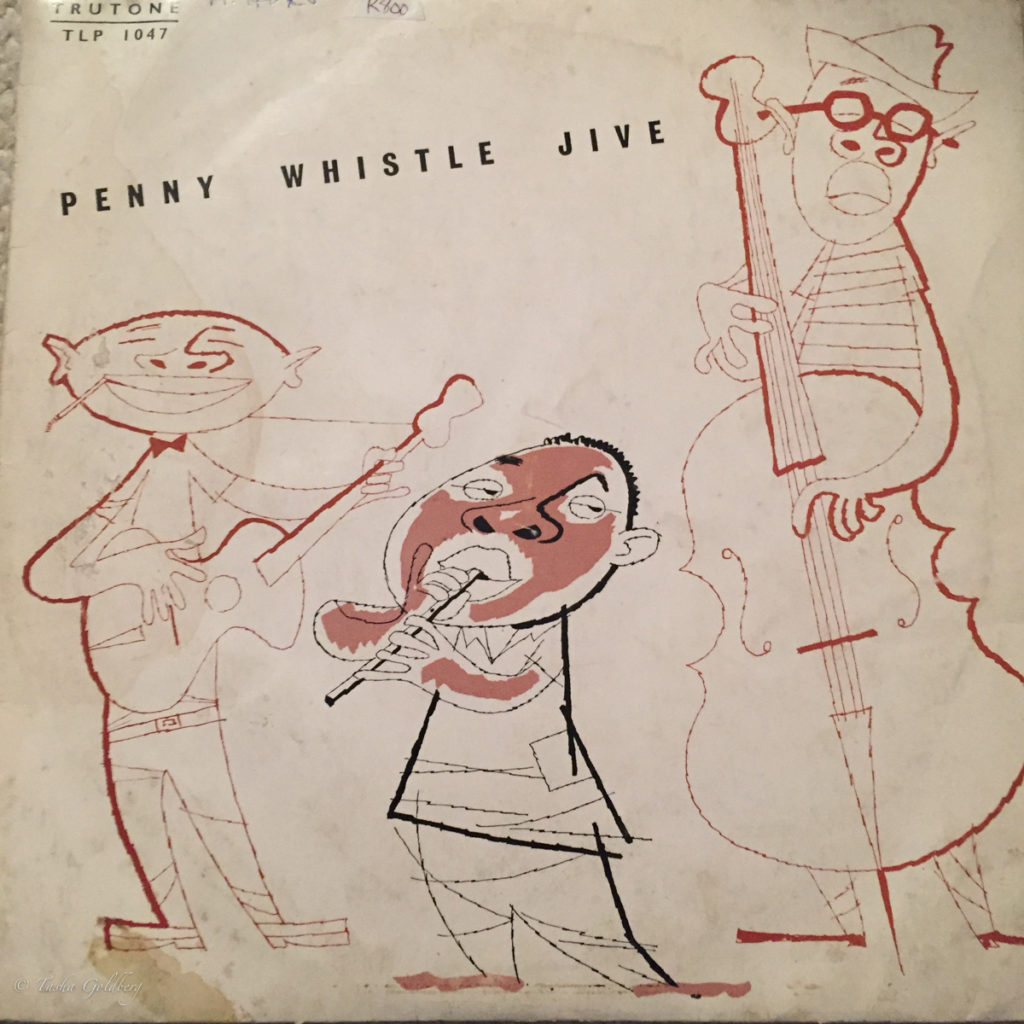

Scoring a good find in a big dig is harder to work for, therefore the sweeter to savor. I had miles to cover, digging through records by the thousands among the eight stories of collections. It was a group of fat little jazz cats atop a cover that flagged my eye to the 10-inch Penny Whistle Jive. It took me all of about 20 seconds to add the treasure to my “for sure” stack. I have always been particularly fond of the flute, the way tight vibrations of sound dovetail into high pitches that literally fly above the base of its song. Admittedly, I have fallen in love in blue-lit basements with my eyes closed, chasing trails left by a flute. I have danced alone among crowds, mesmerized by the sweet shimmering sound of a whistle. And jive? Well, that’s pretty much an open-door invitation. If you feel it, you know it. Don’t have the words? Make them up, just make them up pretty. When I flipped the album over and found that this wax was actually a compilation of famous penny whistle jive-jazzers from Jozi, the deal was sealed. Yes! Yes to an introduction to a new place in sound, one where by feeling good, I was there.

Jive has one of those circular histories where it seems that early African-influenced music met up with blues, jazz and swing to form a new patois: a patois with cross-racial appeal that everyone could dance to. African and American seeds formed a hybrid that hitched to Europe on the backs of soldiers and radio waves where the U.K. blokes named it jive.…or something like that. In South Africa, a similar blend of street music, marabi township jazz, evolved into what is known as kwela. In Zulu, kwela is a call to “get up,” referring to the blended beats that invite all to join. During the shadow of apartheid rule in South Africa, police vans were also called kwela-kwela in Zulu. So a band playing in the street had homies positioned down the block to warn them when police were around. Not as a game, but as dedication to protecting their sanctuaries of sound. In neighboring Malawi, where many of the known kwela producers hail from, the Chichewa word means “to climb.” Both jive and kwela stamp sounds with the notion that unity is achieved through the harmony of diversity.

Jive and kwela have mechanic logic, taking whatever you have, and making it good enough that folks around will get up and dance. In music of a people, accessibility is king. The first documented use of a penny whistle reaches back to the year 1790. The penny whistle has been an instrument easily available to any- and everyone, giving individuals with sonic tendencies a chance to hear what the music inside them sounded like. “Musicians who could not afford band instruments imitated big-band music on penny whistle [and] several of South Africa’s jazz saxophonists started their musical careers on this instrument.” (Lara Allen, Circuits of Recognition and Desire in the Evolution of Black South African Popular Music: The Career of the Penny Whistle). Penny Whistle Jive features a selection of greats who pressed songs through a flageolet or flippie flute, a simple cylindrical pipe with a mouthpiece at one end and open at the other. The instrument intrigues by being generally a wind instrument, cradling breath to song. But it also has a percussive element: the tapping of fingers over small round holes, and the rhythmic space in between breaths often catches a drum-like beat.

According to record liner notes “…. Jim doesn’t know all this, he just calls it a Penny Whistle, and blows ‘lo jive’ on it…!” Facts were filtered from European promoter Alfredo Papo in such a way that he seems to gain a bit of shine for putting the world to it. A genuine jazz cat himself, born in Milan to a Sephardic Spanish family, he held the free form of jazz as a symbol of resistance during Nazi invasion. His family was forced to flee from home in 1943 and resettled in Barcelona. Taking jazz with him, he ran the Hot Club of Barcelona, internationally known for hosting American jazz greats like Duke Ellington and Count Basie. Perhaps most remarkable in his tale of survival was that he loved jazz—but not just for himself, for everyone. Valuing that the ability to find freedom by the lead of jazz was cathartic, a portal of knowing, and something that everyone should be able to access. Inspired by his ethos, he managed to work out some sponsorships to keep ticket prices low.

The discovery of penny whistle jive was probably as easy for Papo as it was for my “for sure” stack—it had the jazz he loved and the level playing field he respected. Papo saw a window to tap into the international appeal of jive and jazz and bring something special, the South African sounds. And he was absolutely on target, kwela rose to international fame easily and quickly. According to the Electric Jive blog, by the end of the 1950s kwela was global, from the U.K., U.S., Argentina, Spain, Singapore to France, Germany, Rhodesia and, of course, South Africa.

The album was compiled in 1959. Each track is so authentic it feels familiar, proud sounds of sweet souls. One of my favorites is “Black John,” played by Peter Makana. According to Papo’s liner notes, Makana is the Cool Boy accompanied by the experimenter of new sounds, Ben Nkosi, who, although also a penny whistler, plays guitar on this track. The trot takes the listener on a journey in the heart, rather than delivering us directly to the moment of love. The result is a spectrum of sound that far outreaches the expected narrow palette of what a whistle can blow. The track was popular, being released four times on different albums.

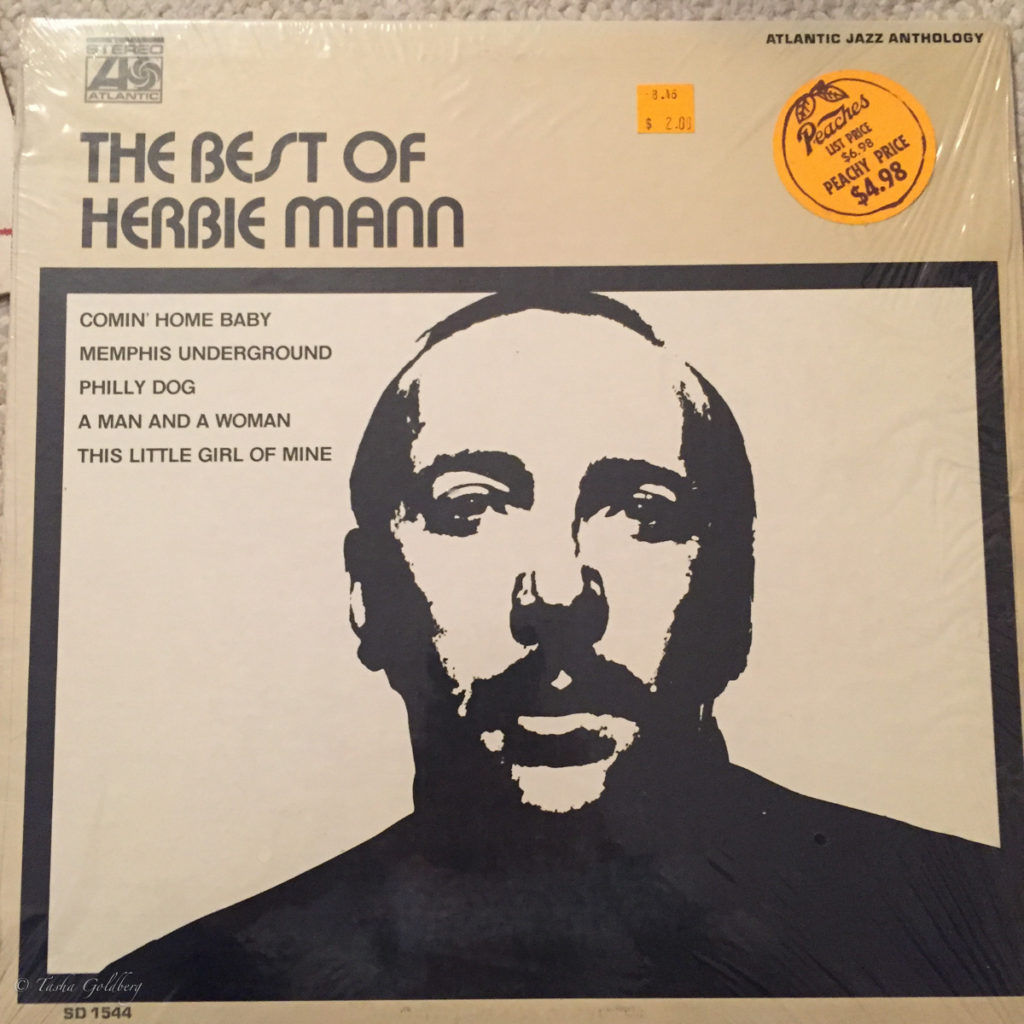

The penny whistle could have a connection to the emerging Afrojazz scene to which Herbie Mann brought heat. On the back of the Best of Herbie Mann album, it recalls Mann’s 1959 debut playing flute with the Afro Jazz Sextet, a band “without precedent or parallel in contemporary music” that opened at a New York club. A few years later, he toured 15 African countries under the State Department. And what came of that? For one, a sensibility of traveling the world and relating to it with sonic stylings. An automatic “yes…let’s find the pocket.” The sounds of flute and whistle have held herders’ heads high in South Africa, broken barriers among races in jazz clubs across the U.S., and hung hope in the air in war-torn Europe. Lucky for us, with the drop of a needle, we still have access to unity, to the jazz in jive.